Elizabeth Comyn a Historical Novel Honors Thesis Creative Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 15: 2012

Patron: Robert Hardy Esq.CBE FSA Issue 15: 2012 OUR OBJECTS To promote the permanent preservation of the battlefield and other sites associated with the Battle of Tewkesbury, 1471, as sites of historic interest, to the benefit of the public generally. To promote the educational possibilities of the battlefield and associated sites, particularly in relation to medieval history. To promote, for public benefit, research into matters associated with the sites, and to publish the useful results of such research. OUR AIMS Working with the owners of the many sites associated with the battle of Tewkesbury, the Society will raise public awareness of the events of the battle and promote the sites as an integrated educational resource. We will encourage tourism and leisure activities by advertising, interpretation and presentation in connection with the sites. We will collate research into the battle and encourage further research, making the results publicly available through a variety of media. In pursuing our objects we will work alongside a variety of organisations in Tewkesbury and throughout the world. We will initiate projects and assist with fundraising and managing them as required. We aim to be the Authority on the battle and battle sites. i. 2 CONTENTS The Arrivall 2 Sir Robert Baynton 3 Blanche Heriot and the Curfew Bell 10 John Leland 11 Trip to the North 13 Holm Castle 14 In Honour and Blood 25 The Arrivall: A Poem 27 Finds 29 i. 1 THE ARRIVALL 2012 has been a year of intense activity on the commemorative statue front. Lots of hard work which is quickly coming to fruition. -

I Some General Points Section I

-- SOME QUERIES ON HISTORICAL DETAIL A Report on World Without End a novel by Ken Follett, first draft Commissioned from Geoffrey Hindley for 31 I 07 I 06 Submitted by email attachment 01 I 08 I 06 The Report has rwo sections I Some general points II Points of detail noted by page numbered references Section I : Some general points: -A] ·dukes' etc Ken, a North Walian friend tells me that the sons of Cymru refer among themselves to our lot as Saes6n nevertheless, to the best of my knowledge there never was an archbishop of Monmouth p. 505, (though there was an archbishop of Lichfield in the late 700s!). I suppose the archbishop can be granted on the grounds of poetic licence but a duke of Monmouth (e.g. p. 34 7) does have me a little worried as a medievalist and not by the anachronistic pre-echo of the title of Charles II's bastard. On a simple fact of historical accuracy, I should point out that whereas the title was known on the continent - duke ofNormandy, duke of Saxony, duke of Brittany etc - up to 1337 the title of' 'duke' was unknown among English aristocratic nomenclature. The first award was to Edward III's eldest son (the Black Prince) as 'duke' of Cornwall (hitherto the duchy had been an earldom). The second ducal title was to Henry Grosmont elevated as 'Duke of Lancaster' in 1361. He too was of royal blood being in the direct male descent from Henry III's son Edmund Crouchback. His father the second earl of course lost his head after his defeat at the battle of Boroughbridge. -

Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship

Quidditas Volume 13 Article 2 1992 Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship Carolyn P. Schriber Rhodes College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schriber, Carolyn P. (1992) "Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship," Quidditas: Vol. 13 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol13/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship* Carolyn P. Schriber Rhodes College dward II (1307-1327) succeeded to the throne of England at a crucial time. In 1307 England was at war with Scotland and faced E threats of further trouble in Wales and Gascony. In addition his father had left him a debt-ridden country in which the barons were beginning to recognize their potential for governmental control through financial blackmail. The country's finances were overextended, but the baronage and clergy had been resisting royal demands for increased taxation. If Edward II were to continue his father's policies and pursue the war in Scotland, as the barons wished, he would be forced to give in to unrelated baronial demands in exchange for military financing. If, instead, he followed his natural inclinations toward a policy of peace, he would encourage further baronial opposition. -

Magna Carta in the Fourteenth Century: from Law to Symbol?: Reflections on the “Six Statutes”

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 25 (2016-2017) Issue 2 Symposium: After Runnymede: Revising, Reissuing, and Reinterpreting Magna Article 9 Carta in the Middle Ages December 2016 Magna Carta in the Fourteenth Century: From Law to Symbol?: Reflections on the “Six Statutes” Charles Donahue Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Legal History Commons Repository Citation Charles Donahue Jr., Magna Carta in the Fourteenth Century: From Law to Symbol?: Reflections on the “Six Statutes”, 25 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 591 (2016), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmborj/vol25/iss2/9 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj MAGNA CARTA IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY: FROM LAW TO SYMBOL?: REFLECTIONS ON THE “SIX STATUTES” Charles Donahue, Jr.* Faith Thompson’s 1948 book on Magna Carta from 1300 to 1629 is not cited as often today as is her book on the first century of Magna Carta, which was pub- lished twenty-three years earlier.1 That, in a way, is a shame. Both books are, of course, informed by an overall vision of English constitutional history that modern scholarship would want to qualify. But Thompson was a careful scholar, whose citations are almost always accurate, and who was well aware that the views of the Charter that were promulgated by Sir Edward Coke and John Selden in the seven- teenth century were anachronistic. My concern here is with the fourteenth century. -

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman In 1215, Genghis Khan conquered Beijing on the way to creating the Mongol Empire. The 23rd of September 2015 was the 800th anniversary of the birth of his grandson, Kublai Khan, under whose imperial rule, as the founder of the Yuan dynasty, the extent of the China we know today was determined. 1215 was a big year for executive power. This 800th anniversary of Magna Carta should be approached with a degree of humility. Underlying themes In two earlier addresses during this year’s caravanserai of celebration,1 I have set out certain themes, each recognisably of constitutional significance, which underlie Magna Carta. In this address I wish to focus on four of those themes, as they developed over subsequent centuries, and to do so with a focus on the executive authority of the monarchy. The themes are: First, the king is subject to the law and also subject to custom which was, during that very period, in the process of being hardened into law. Secondly, the king is obliged to consult the political nation on important issues. Thirdly, the acts of the king are not simply personal acts. The king’s acts have an official character and, accordingly, are to be exercised in accordance with certain processes, and within certain constraints. Fourthly, the king must provide a judicial system for the administration of justice and all free men are entitled to due process of law. In my opinion, the long-term significance of Magna Carta does not lie in its status as a sacred text—almost all of which gradually became irrelevant. -

The Career of Sir Guy Ferre the Younger 1298-1320

~!' .. : • ...:h OFVlRC GAARLOTFI The Maintenance of Ducal Authority in Gascony: ttBRJ The Career of Sir Guy Ferre the Younger 1298-1320 Jay Lathen Boehm IN the letters patent by which Edward ITinformed the constable of Bordeaux that Sir Guy Ferre the Younger had been appointed to the seneschalsy of Gascony, the king clearly articulated that the seneschal's primary responsibility was to maintain the jus et honor of the king-duke throughout the duchy of Aquitaine. 1 As the income Edward II derived from his tenure of the duchy exceeded that of all the English shires combined, 2 he not surprisingly exerted great effort to maintain his administrative and judicial presence in what remained to him of the so-called Angevin empire. Continuing disputes, however, over the nature and performance of the liege homage owed since 1259 to the Capetian monarchs made residence in the duchy problematic for the kings of England. As a consequence, both Edward I and bis son, Edward IT,elected to administer Gascony by delegating their ducal authority to household retainers or clients, official representatives, and salaried ministers. At various times from 1298 to 1320, Sir Guy Ferre the Younger served in Gascony in all of these capacities, as both comital administrator and advocate for the maintenance of ducal authority. Rather than focus on the mechanical details involved in the actual administration of the duchy, this study, by following the career of a model ducal representative, examines the strengths and weaknesses of the policy adopted by the absentee Plantagenet king-dukes for maintaining ducal authority against their increasingly invasive Capetian over-lords. -

Christopher DODINGTON Peter DODINGTON Joan BUCKLAND

Clodoreius ? Born: 0320 (app) Flavius AFRANIUS Syagrius Julius AGRICOLA Born: 0345 (app) Born: 0365 (app) Occup: Roman proconsul Occup: Roman praetorian prefect & consul Died: 0430 (app) Ferreolus ? Syagria ? ? Born: 0380 (app) Born: 0380 (app) Born: 0390 (app) Prefect Totantius FERREOLUS Papianilla ? King Sigobert the Lame of the Born: 0405 Born: 0420 (app) FRANKS Occup: Praetorian Prefect of Gaul Occup: Niece of Emperor Avitus Born: 0420 (app) Occup: King of the Franks, murdered by his son Died: 0509 (app) Senator Tonantius FERREOLUS Industria ? King Chlodoric the Parricide of King Cerdic of WESSEX Born: 0440 Born: 0450 (app) the FRANKS Born: 0470 (app) in Land of the Occup: Roman Senator of Narbonne Born: 0450 (app) Saxons, Europe Died: 0517 Occup: King of the Franks Occup: First Anglo Saxon King of Died: 0509 Wessex Died: 0534 Senator Ferreolus of Saint Dode of REIMS Lothar ? King Cynric of WESSEX NARBONNE Born: 0485 (app) Born: 0510 (app) Born: 0500 (app) Born: 0470 Occup: Abbess of Saint Pierre de Occup: King of Wessex Occup: Senator of Narbonne Reims & Saint Marr: 0503 (app) Senator Ansbertus ? Blithilde ? King Ceawlin of WESSEX Born: 0520 (app) Born: 0540 (app) Born: 0530 (app) Occup: Gallo-Roman Senator Occup: King of Wessex Died: 0593 Baudegisel II of ACQUITAINE Oda ? Arnaold of METZ Oda ? Carloman ? Arnaold of METZ Oda ? Saint Arnulf of METZ Saint Doda of METZ Cuthwine of WESSEX Born: 0550 (app) Born: 0560 (app) Born: 0560 (app) Born: 0570 (app) Born: 0550 (app) Born: 0560 (app) Born: 0570 (app) Born: 0582 (app) Born: 0584 -

MEDIAEVAL ENGLAND T • ERC"VMENT ATABAY Il .• SECTION XVIII the NATURE of PARLIAMENT

r STUDIES iN THE CONSTITUTION OF MEDIAEVAL ENGLAND t • ERC"VMENT ATABAY il .• SECTION XVIII THE NATURE OF PARLIAMENT it is worth recalling that the representative members came rather un willingly - particularly the burgesses - however they were thus given a chance of presenting petitions. Parliament under Edward 1 was just a casmıl collection of individuals anxious to get home, and the part they played in par liament was not of great practical importance. The factor that gradually wel ded the two orders was the Common Petition. in Edward I's time they pro bably sat apart for the purpose of deliberations, and it is very unlikely tlhat the deliberations of the burgesses were of any importance at ali. However they succeeded in attaching themselves to the knights, and in the early XIVth cen tury separate consultations became rarer and joint ones more usual, until by the middle of the century it had become a regular procedure. 'Commons' originally meant 'communes', that is shires or counties - those representing communal bodies. When Parliament was assembled knights and burgesses were charged with petitions to be dealt with by the King in Council. These were mainly private, but some came from county courts. At the beginning of the XIVth century an obvious tendency was for the bearers of these petitions to make as many as possible of them into a single common petition and send it in with the whole weight of tlhe order behind it. By the beginning of Edward III' s reign we see that knights and burgesses used to get together to discuss the petitions with which they were charged, and make up a Common Pehtion which was subquently presented in Parliament. -

The Legacy of Magna Carta: Law and Justice in the Fourteenth Century

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 25 (2016-2017) Issue 2 Symposium: After Runnymede: Revising, Reissuing, and Reinterpreting Magna Article 10 Carta in the Middle Ages December 2016 The Legacy of Magna Carta: Law and Justice in the Fourteenth Century Anthony Musson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Legal History Commons Repository Citation Anthony Musson, The Legacy of Magna Carta: Law and Justice in the Fourteenth Century, 25 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 629 (2016), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol25/iss2/10 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THE LEGACY OF MAGNA CARTA: LAW AND JUSTICE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY Anthony Musson* INTRODUCTION Scholarly focus on Magna Carta in the fourteenth century has generally been on what might be termed the public law or constitutional aspects. The Great Charter was frequently invoked in the political discourse of the time and became enshrined in the lexicon of constitutional debate between the king and his subjects.1 Magna Carta’s prominence in the fourteenth century owed much to its confirmation during the 1297 constitutional crisis,2 which brought formal assimilation as part of the common law (la grande chartre des franchises cume lay commune), an event that revived and refocused the attention of the legal profession.3 With historical hindsight, though, it was the con- firmation of Magna Carta as a point of principle in the so-called ‘six statutes’ (“four- teenth-century interpretations of the Magna Carta”)4 and its employment in the ‘Record and Process’ against Richard II—the official parliamentary justification for his deposi- tion in 13995 that firmly embedded the Great Charter in legal and political theory.6 * The author is grateful to the delegates at the William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal’s 2016 Symposium and to Professor Mark Ormrod for comments on the text. -

Selected Ancestors of the Chicago Rodger's

\ t11- r;$1,--ff" :fi-',v--q-: o**-o* *-^ "n*o"q "I-- 'Ita^!cad$l r.rt.H ls $urq1 uodi uoFour) puE au^l ete)S d-- u.uicnv ls 000'988'Z: I reJo+ uodn oi*cflaN llrprPa srE " 'sauepuno8 laqlo n =-^-Jtos,or lluunspue0NvrulsflnHlu0N -'- 'NVeU0nvt! 0twr0t ---" """ 'salrepuno8 rluno3 i ,- e s(llv1st leNNVtrc sr3tm3 a^nPnsu upr aqt 3'NVEI -__-,,sau?puno6leuorlPL.arLt ] tsF s!-d: ' 6@I Si' Wales and England of Map 508 409 8597 409 508 pue puel0L rrsl'19N9 salen om [email protected] -uv*t' please contact David Anderson at: Anderson David contact please 1,N For additional information, additional For + N 'r'oo"' lojr!rB "tA^ .*eq\M ""t \uir - s ,s *'E?#'lj:::",,X. ."i",i"eg"'. Wo, r rii': Fl?",:ll.jl,r ,s *,,^ . l"lfl"'" 1SVo! s.p, ;eG-li? ol.$q .:'N" avl r'/ !',u l.ltll:,wa1 H'. P " o r l\);t; !ff " -oNv P-9 . \ . ouorrufq 6 s 'dM .ip!que3 /,.Eer,oild.,.r-ore' uot-"'j SIMOd ) .,,i^.0'"i'"'.=-1- 4.1 ...;:,':J f UIHS i";,.i*,.relq*r -l'au8.rs.rd1'* tlodtiod * 1- /I!!orq8,u! l&l'p4.8 .tr' \ Q '-' \ +lr1: -/;la-i*iotls +p^ .) fl:Byl''uo$!eH l''",,ili"l,"f \ ,uoppor .q3norcq.trrv i ao3!ptDj A rarre;'a\ RUPqpuou^M. L,.rled. diulMoo / ) n r".c14!k " *'!,*j ! 8il5 ^ris!€i<6l-;"qrlds qteqsu uiraoos' \u,.".',"u","on". ' \. J$Pru2rl 3rEleril. I ubFu isiS. i'i. ,,./ rurHSNtoiNll AM-l' r- 'utqlnx i optow tstuuqlt'" %,.-^,r1, ;i^ d;l;:"f vgs "".'P"r;""; --i'j *;;3,1;5lt:r*t*:*:::* HTVON *",3 r. -

THE LADIES De CLARE & the POLITICS of the 14Th CENTURY

THE LADIES de CLARE & THE POLITICS OF THE 14th CENTURY lot has been written about the Despenser’s and Piers Gaveston (who even has a ‘secret’ Society named after him), so it seems pointless repeating much of it here, but I have often A wondered what their wives, Eleanor and Margaret de Clare thought of what their respective husbands were up to, and whether the two sisters ever met to discuss their plight whilst they were near neighbours at Woking and Byfleet? Eleanor de Clare was the eldest daughter of Eleanor was a great favourite of her uncle, The Coat of Arms of Gilbert de Clare (the 6th Earl of Hertford, 7th Earl Edward II, who apparently ‘paid her living Gilbert de Clare, 7th of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan), and his expenses throughout his reign’, with payments Earl of Hertford, 8th second wife Joan of Acre, who was the daughter being made from the Royal Wardrobe accounts Earl of Gloucester. of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was for clothes and other items – a privilege that born in 1292 at Caerphilly Castle and in 1306 even his two sisters didn’t enjoy! She was the at the age of thirteen or fourteen was married principal lady-in-waiting to Queen Isabella and to Hugh le Despenser the Younger when he was even had her own retinue, headed by her own Countess of Cornwall. Instead Edward II gave about twenty. chamberlain, John de Berkenhamstead. her Oakham Castle and from 1313 to 1316 she was High Sheriff of Rutland. As a grand-daughter of Edward I she was Margaret de Clare was the second eldest de obviously quite a catch for the Younger Clare daughter. -

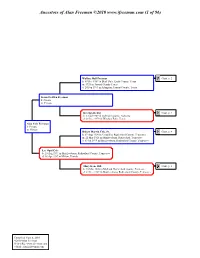

Graphic Family Tree-39 Gens to 750AD

Ancestors of Alan Freeman ©2010 www.ifreeman.com (1 of 96) Wallace Hall Freeman Cont. p. 2 b: 09 Dec 1907 in Bluff Dale, Erath County, Texas m: 1928 in Tarrant County Texas d: 24 Sep 1973 in Arlington, Tarrant County, Texas Kenneth Allen Freeman b: Private m: Private Eva Estelle Day Cont. p. 3 b: 13 Jul 1909 in Cullman County, Alabama d: 01 Dec 1979 in Witchita Falls, Texas Alan Cole Freeman b: Private m: Private Robert Marvin Cole, Sr. Cont. p. 4 b: 07 Aug 1900 in Versailles, Rutherford County, Tennessee m: 21 Mar 1926 in Murfreesboro, Rutherford, Tennessee d: 07 Jul 1979 in Murfreesboro, Rutherford County, Tennessee Lee Opal Cole b: 20 Aug 1931 in Murfreesboro, Rutherford County, Tennessee d: 18 Apr 1997 in Milton, Florida Mary Irene Hill Cont. p. 5 b: 16 Mar 1906 in Midland, Rutherford County, Tennessee d: 21 Dec 1989 in Murfreesboro, Rutherford County, Tennessee Compiled: Sept. 6, 2010 ©2010 Alan Freeman Web-URL: www.ifreeman.com e-Mail: [email protected] Ancestors of Alan Freeman ©2010 www.ifreeman.com (2 of 96) Wesley Newell Freeman Cont. p. 6 b: 12 Dec 1832 in Ellijay, Henry County, Georgia m: 13 Feb 1881 in Granbury, Hood County, Texas d: 26 Jan 1891 in Bluff Dale, Erath County, Texas Olin Knight Freeman b: 09 Sep 1885 in Bluff Dale, Erath County, Texas m: 22 Sep 1906 in Granbury, Hood County, Texas d: 02 Sep 1940 in Sherman, Texas Julia Emma Gordon Cont. p. 7 b: 28 Jan 1845 in Pine Log, Cass County, Georgia d: 10 Dec 1915 in Bluff Dale, Erath County, Texas Wallace Hall Freeman b: 09 Dec 1907 in Bluff Dale, Erath County, Texas m: 1928 in Tarrant County Texas d: 24 Sep 1973 in Arlington, Tarrant County, Texas Henry Taylor Hall Cont.