F. KING MAKING and UNMAKING Edward II in S&M, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View 2019 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 Front Court, engraved by R B Harraden, 1824 VOL CI MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 The Master, Dame Fiona Reynolds, in the new portrait by Alastair Adams May Ball poster 1980 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2018–2019 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2020. News about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/members/keepintouch. College enquiries should be sent to [email protected] or addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. General correspondence concerning the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. Correspondence relating to obituaries should be addressed to the Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, with a special nod to the unstinting assistance of the College Archivist. -

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

THE JUDICIARY OP TAP Oupcrior COURTS 1820 to 1968 : A

THE JUDICIARY OP TAP oUPCRIOR COURTS 1820 to 1968 : A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY A tiiesis presented for the lAPhilo degree University of London. JENNIFER MORGAl^o BEDFORD COLLEGE, 1974. ProQuest Number: 10097327 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10097327 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Aijstract This study is an attempt to construct o social profile of the Juoiciary of the superior courts uurin^ the period 1 8 20-1 9 6 8. The analyses cover a vio: raepe of characteristics iacluuiap parental occupation, schooling, class op degree, ape of call to toæ luu' ^aa ape at appolnt^/^ent to tue -each. These indices are used to deter..line how far opportunities for recruitment to the dench lave seen circumscribed by social origin, to assess the importance of academic pualificaticns and vocational skills in the achievement of professional success and to describe the pattern of the typical judicial career. The division of the total population of judges into four cohorts, based on the date of their initial appointment to the superior courts, allows throughout for historical comparison, demonstrating the major ^oints of change and alsu underlining the continuities in tne composition of the Bench during the period studied. -

CONTENTS Editorial I Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

VOL. LVI. No. 173 PRICE £1 函°N加少 0 December, 1973 CONTENTS Editorial i Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford ... 11 Othello ... 17 Ex Deo Nascimur 31 Bacon's Belated Justice 35 Francis Bacon*s Pictorial Hallmarks 66 From the Archives 81 Hawk Versus Dove 87 Book Reviews 104 Correspondence ... 111 © Published Periodically LONDON: Published by The Francis Bacon Society IncorporateD at Canonbury Tower, Islington, London, N.I, and printed by Lightbowns Limited, 72 Union Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight. THE FRANCIS BACON SOCIETY (INCORPORATED) Among the Objects for which the Society is established, as expressed in the Memorandum of Association, are the following 1. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the study of the works of Francis Bacon as philosopher, statesman and poet; also his character, genius and life; his- — . influence: — £1._ _ — — — on his1" — own and J succeeding— J : /times, 〜— —and the tendencies cfand」 v*results 否 of his writing. 2. To encourage for the benefit of the public, the general study of the evidence in favour of Francis Bacon's authorship of the plays commonly ascribed to Shakespeare, and to investigate his connection with other works of the Elizabethan period. Officers and Council: Hon, President: Cmdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Past Hon, President: Capt. B, Alexander, m.r.i. Hon. Vice-Presidents: Wilfred Woodward, Esq. Roderick L. Eagle, Esq. Council: Noel Fermor, Esq., Chairman T. D. Bokenham, Esq., Vice-Chairman Cmdr. Martin Pares, R.N. Nigel Hardy, Esq. J. D. Maconachie, Esq. A. D. Searl, Esq. Sidney Filon, Esq. Austin Hatt-Arnold, Esq. Secretary: Mrs. D. -

I Some General Points Section I

-- SOME QUERIES ON HISTORICAL DETAIL A Report on World Without End a novel by Ken Follett, first draft Commissioned from Geoffrey Hindley for 31 I 07 I 06 Submitted by email attachment 01 I 08 I 06 The Report has rwo sections I Some general points II Points of detail noted by page numbered references Section I : Some general points: -A] ·dukes' etc Ken, a North Walian friend tells me that the sons of Cymru refer among themselves to our lot as Saes6n nevertheless, to the best of my knowledge there never was an archbishop of Monmouth p. 505, (though there was an archbishop of Lichfield in the late 700s!). I suppose the archbishop can be granted on the grounds of poetic licence but a duke of Monmouth (e.g. p. 34 7) does have me a little worried as a medievalist and not by the anachronistic pre-echo of the title of Charles II's bastard. On a simple fact of historical accuracy, I should point out that whereas the title was known on the continent - duke ofNormandy, duke of Saxony, duke of Brittany etc - up to 1337 the title of' 'duke' was unknown among English aristocratic nomenclature. The first award was to Edward III's eldest son (the Black Prince) as 'duke' of Cornwall (hitherto the duchy had been an earldom). The second ducal title was to Henry Grosmont elevated as 'Duke of Lancaster' in 1361. He too was of royal blood being in the direct male descent from Henry III's son Edmund Crouchback. His father the second earl of course lost his head after his defeat at the battle of Boroughbridge. -

Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship

Quidditas Volume 13 Article 2 1992 Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship Carolyn P. Schriber Rhodes College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schriber, Carolyn P. (1992) "Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship," Quidditas: Vol. 13 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol13/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Edward II and the Tactics of Kingship* Carolyn P. Schriber Rhodes College dward II (1307-1327) succeeded to the throne of England at a crucial time. In 1307 England was at war with Scotland and faced E threats of further trouble in Wales and Gascony. In addition his father had left him a debt-ridden country in which the barons were beginning to recognize their potential for governmental control through financial blackmail. The country's finances were overextended, but the baronage and clergy had been resisting royal demands for increased taxation. If Edward II were to continue his father's policies and pursue the war in Scotland, as the barons wished, he would be forced to give in to unrelated baronial demands in exchange for military financing. If, instead, he followed his natural inclinations toward a policy of peace, he would encourage further baronial opposition. -

On the Relations Between England and Rome

R I LIST OF BOOKS TO W HICH REFE ENCE S MADE . i bbatum Ril . R ll i . Alban S . Gesta a ( ey) o s Ser es ’ ma . A i . C i in i i z . G lber c hron con , Le bn t s Script rer er n H . Luard . Rolls i . Annales Monastici ( . R ) Ser es l ed . M i. Ba uzii Miscellanea. ans i l m was Bouquet ; Recueil de s historiens de la France xxx. (Th s vo u e ' ’ edi d b E i l I e d it d m l. te y r a , but have cit un er Bouquet s na e as usua ) ri Uni . Parisiensis. Bulae us ; Histo c. v ’ Bulletin du comité historique des monuments écrits sur l histoire de 11 . 1860 France, (Par. ) l Ri d Re istrum rioratus omn. m x D li . But er, char , g p Sanctoru ju ta ub n D hl. 1845 u . D d l Mo nasticon An li m ed . nov. ug a e , g canu ( ) . vol. D un elm ensis Hi stories scriptores tres (Surt. Soc ’ u is a . Eccleston de adventu minorum in Brewer s Mon ments. Franc can (Rolls Series) . ’ E liensis monachi Hi storia E liensis (Wharton s Anglia Sacra) . m Ch i de M . R ll i Evesha , ron con ( acray) o s Ser es . Finchale Re istrum rioratus de . Soc. vol. , g p (Surt. d di i Foedera I . R . , ecor e t on M m i l of albran oc ol. 42 . in W . -

Bell's Cathedrals: Chichester (1901) by Hubert C

Bell's Cathedrals: Chichester (1901) by Hubert C. Corlette Bell's Cathedrals: Chichester (1901) by Hubert C. Corlette Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Victoria Woosley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: CHICHESTER CATHEDRAL FROM THE SOUTH.] THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF CHICHESTER A SHORT HISTORY & DESCRIPTION OF ITS FABRIC WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE DIOCESE AND SEE HUBERT C. CORLETTE A.R.I.B.A. WITH XLV ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON GEORGE BELL & SONS 1901 page 1 / 148 PREFACE. All the facts of the following history were supplied to me by many authorities. To a number of these, references are given in the text. But I wish to acknowledge how much I owe to the very careful and original research provided by Professor Willis, in his "Architectural History of the Cathedral"; by Precentor Walcott, in his "Early Statutes" of Chichester; and Dean Stephen, in his "Diocesan History." The footnotes, which refer to the latter work, indicate the pages in the smaller edition. But the volume could never have been completed without the great help given to me on many occassions by Prebendary Bennett. His deep and intimate knowledge of the cathedral structure and its history was always at my disposal. It is to him, as well as to Dr. Codrington and Mr. Gordon P.G. Hills, I am still further indebted for much help in correcting the proofs and for many valuable suggestions. H.C.C. C O N T E N T S. CHAP. PAGE I. HISTORY OF THE CATHEDRAL............... 3 page 2 / 148 II. THE EXTERIOR.......................... 51 III. THE INTERIOR.......................... 81 IV. -

Magna Carta in the Fourteenth Century: from Law to Symbol?: Reflections on the “Six Statutes”

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 25 (2016-2017) Issue 2 Symposium: After Runnymede: Revising, Reissuing, and Reinterpreting Magna Article 9 Carta in the Middle Ages December 2016 Magna Carta in the Fourteenth Century: From Law to Symbol?: Reflections on the “Six Statutes” Charles Donahue Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Legal History Commons Repository Citation Charles Donahue Jr., Magna Carta in the Fourteenth Century: From Law to Symbol?: Reflections on the “Six Statutes”, 25 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 591 (2016), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmborj/vol25/iss2/9 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj MAGNA CARTA IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY: FROM LAW TO SYMBOL?: REFLECTIONS ON THE “SIX STATUTES” Charles Donahue, Jr.* Faith Thompson’s 1948 book on Magna Carta from 1300 to 1629 is not cited as often today as is her book on the first century of Magna Carta, which was pub- lished twenty-three years earlier.1 That, in a way, is a shame. Both books are, of course, informed by an overall vision of English constitutional history that modern scholarship would want to qualify. But Thompson was a careful scholar, whose citations are almost always accurate, and who was well aware that the views of the Charter that were promulgated by Sir Edward Coke and John Selden in the seven- teenth century were anachronistic. My concern here is with the fourteenth century. -

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman

Magna Carta and the Executive James Spigelman In 1215, Genghis Khan conquered Beijing on the way to creating the Mongol Empire. The 23rd of September 2015 was the 800th anniversary of the birth of his grandson, Kublai Khan, under whose imperial rule, as the founder of the Yuan dynasty, the extent of the China we know today was determined. 1215 was a big year for executive power. This 800th anniversary of Magna Carta should be approached with a degree of humility. Underlying themes In two earlier addresses during this year’s caravanserai of celebration,1 I have set out certain themes, each recognisably of constitutional significance, which underlie Magna Carta. In this address I wish to focus on four of those themes, as they developed over subsequent centuries, and to do so with a focus on the executive authority of the monarchy. The themes are: First, the king is subject to the law and also subject to custom which was, during that very period, in the process of being hardened into law. Secondly, the king is obliged to consult the political nation on important issues. Thirdly, the acts of the king are not simply personal acts. The king’s acts have an official character and, accordingly, are to be exercised in accordance with certain processes, and within certain constraints. Fourthly, the king must provide a judicial system for the administration of justice and all free men are entitled to due process of law. In my opinion, the long-term significance of Magna Carta does not lie in its status as a sacred text—almost all of which gradually became irrelevant. -

The Career of Sir Guy Ferre the Younger 1298-1320

~!' .. : • ...:h OFVlRC GAARLOTFI The Maintenance of Ducal Authority in Gascony: ttBRJ The Career of Sir Guy Ferre the Younger 1298-1320 Jay Lathen Boehm IN the letters patent by which Edward ITinformed the constable of Bordeaux that Sir Guy Ferre the Younger had been appointed to the seneschalsy of Gascony, the king clearly articulated that the seneschal's primary responsibility was to maintain the jus et honor of the king-duke throughout the duchy of Aquitaine. 1 As the income Edward II derived from his tenure of the duchy exceeded that of all the English shires combined, 2 he not surprisingly exerted great effort to maintain his administrative and judicial presence in what remained to him of the so-called Angevin empire. Continuing disputes, however, over the nature and performance of the liege homage owed since 1259 to the Capetian monarchs made residence in the duchy problematic for the kings of England. As a consequence, both Edward I and bis son, Edward IT,elected to administer Gascony by delegating their ducal authority to household retainers or clients, official representatives, and salaried ministers. At various times from 1298 to 1320, Sir Guy Ferre the Younger served in Gascony in all of these capacities, as both comital administrator and advocate for the maintenance of ducal authority. Rather than focus on the mechanical details involved in the actual administration of the duchy, this study, by following the career of a model ducal representative, examines the strengths and weaknesses of the policy adopted by the absentee Plantagenet king-dukes for maintaining ducal authority against their increasingly invasive Capetian over-lords. -

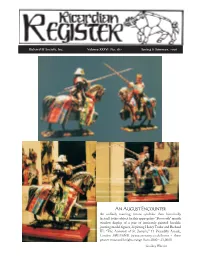

An August Encounter

....... s Richard III Society, Inc. Volume XXXVI No. 1&2 Spring & Summer, 2006 An August Encounter An unlikely meeting, (more symbolic than historically factual) is the subject for this appropriate “Bosworth” month window display of a pair of intricately-painted heraldic jousting model figures, depicting Henry Tudor and Richard III: “The Armoury of St. James’s,” 17 Piccadilly Arcade, London SW1Y6NH (www.armoury.co.uk/home - these pewter mounted knights range from £800 - £1,000!) — Geoffrey Wheeler REGISTER STAFF EDITOR: Carole M. Rike 48299 Stafford Road • Tickfaw, LA 70466 985-350-6101 ° 504-952-4984 (cell) email: [email protected] ©2006 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means — mechanical, RICARDIAN READING EDITOR: Myrna Smith electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval — 2784 Avenue G • Ingleside, TX 78362 without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by (361) 332-9363 • email: [email protected] members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 annually. ARTIST: Susan Dexter 1510 Delaware Avenue • New Castle, PA 16105-2674 In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient CROSSWORD: Charlie Jordan evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every [email protected] possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation.