Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

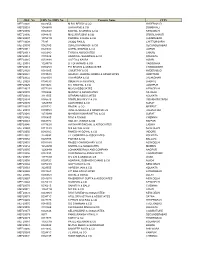

We Had Vide HO Circular 443/2015 Dated 07.09.2015 Communicated

1 CIRCULAR NO.: 513/2015 HUMAN RESOURCES WING I N D E X : STF : 23 INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SECTION HEAD OFFICE : BANGALORE-560 002 D A T E : 21.10.2015 A H O N SUB: IBA MEDICAL INSURANCE SCHEME FOR RETIRED OFFICERS/ EMPLOYEES. ******* We had vide HO Circular 443/2015 dated 07.09.2015 communicated the salient features of IBA Medical Insurance Scheme for the Retired Officers/ Employees and called for the option from the eligible retirees. Further, the last date for submission of options was extended upto 20.10.2015 vide HO Circular 471/2015 dated 01.10.2015. The option received from the eligible retired employees with mode of exit as Superannuation, VRS, SVRS, at various HRM Sections of Circles have been consolidated and published in the Annexure. We request the eligible retired officers/ employees to check for their name if they have submitted the option in the list appended. In case their name is missing we request such retirees to take up with us by 26.10.2015 by sending a scan copy of such application to the following email ID : [email protected] Further, they can contact us on 080 22116923 for further information. We also observe that many retirees have not provided their email, mobile number. In this regard we request that since, the Insurance Company may require the contact details for future communication with the retirees, the said details have to be provided. In case the retirees are not having personal mobile number or email ID, they have to at least provide the mobile number or email IDs of their near relatives through whom they can receive the message/ communication. -

Multidisciplinary Studies Leadership Excellence Dialogues Leading To

Estd. 1988 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Bengaluru, India Cutting Edge Research Multidisciplinary Studies Leadership Excellence Dialogues Leading to Transformations NIAS Brochure July 2016 National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS) was conceived and founded in 1988 by Mr JRD Tata, who sought to create an institution to conduct advanced multidisciplinary research. Housed in a picturesque green campus in Bengaluru the Institute serves as a forum to bring together individuals from diverse intellectual backgrounds. They include administrators and managers from industry and government, leaders in public affairs, eminent individuals in different walks of life, and the academicians in the natural and life sciences, humanities, and social sciences. The objective is to nurture a broad base of scholars, managers and leaders who would respond to the complex challenges that face contemporary India and global society, with insight, sensitivity, confidence and dedication. The Mission To integrate the findings of scholarship in the natural and social sciences with technology and the arts through multi-disciplinary research on the complex issues that face Indian and global society. To assist in the creation of new leadership with broad horizons in all sectors of society by disseminating the conclusions of such research through appropriate publications and courses as well as dialogues with leaders and the public. T HROUGH THE Y EARS NIAS Main Building Mr JRD Tata signing the Golden Book at the inaugural ceremony Mr JRD Tata viewing the model -

The Journal of the Music Academy Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. LXIV 1993 arsr nrafcr a s farstfa s r 3 ii “I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins nor in the Sun; (but) where my bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada!” Edited by T.S. PARTHASARATHY The Music Academy, Madras 306, T.T.K. Road, Madras - 600 014 Annual Subscription -- Inland Rs.40: Foreign $ 3-00 OURSELVES This Journal is published as an Annual. All correspondence relating to the Journal should be addressed and all books etc., intended for it should be sent to The Editor Journal of the Music Academy, 306, T.T.K. Road, Madras - 600 014. Articles on music and dance are accepted for publication on the understanding that they are contributed solely to the Journal of the Music Academy. Manuscripts should be legibly written or, preferably, typewrittern (dounle-spaced and on one side of the paper only) and should be signed by the writer (giving his or her address in full.) The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by contributors in their articles. CONTENTS S.No. Page 1. 66th Madras Music Conference - Official Report 1 2. Advisory Committee Meetings 20 3. The Sadas 47 4. Tyagaraja and the Bhakti Community - William Jackson 70 Princess Rukinini Bai - B.Pushpa 79 6. Indian classical Music - T.S.Parthasarathy 83 Tagore’s Dance concept - Gayatri Chatterjce 97 From Sarn^adeva to Govinda 101 Literary and Prosodical Beauties - T.S. Parthasarathy 107 10. -

Declaration Received for MEF2018-19.Xlsx

MEF_No FRN No./MRN No. Concern Name CITY MEF20001 003265S M R K REDDY & CO HYDERABAD MEF20003 104888W U M KARVE & CO DOMBIVALI MEF20005 006674N BANSAL AGARWAL & CO NEW DELHI MEF20006 008887S MALLIKARJUNA & CO SRIKALAHASTI MEF20007 107591W PARIMAL S SHAH & CO AHMEDABAD MEF20008 77297 JAJOO RANJU CHITTORGARH MEF20009 004278S SURESH PRAKASH & CO SECUNDERABAD MEF20011 002803C GOPAL SHARMA & CO JAIPUR MEF20013 006598C TYAGI & ASSOCIATES UNNAO MEF20014 317082E AGARWAL SAGARMAL & CO KOLKATA MEF20015 005189N GUPTA & KALRA HISAR MEF20018 102457W B T DHARAMSI & CO VADODARA MEF20019 008025N P K BHASIN & ASSOCIATES CHANDIGARH MEF20020 008100S C MURTHY & CO HYDERABAD MEF20021 017453N GAURAV JAGDISH ARORA & ASSOCIATES AMRITSAR MEF20022 014835N V M ARORA & CO JALANDHAR MEF20024 010433C SOBHANI & AGARWAL BHOPAL MEF20025 003102C K C SINGHAL & CO JODHPUR MEF20027 007720N MUKU ASSOCIATES NEW DELHI MEF20030 315048E MANTRY & ASSOCIATES SILIGURI MEF20032 311155E SITARAM ASSOCIATES KOLKATA MEF20034 008657S RAMALINGAM V C & CO VISAKHAPATNAM MEF20035 125289W ALOK KEDIA & CO SURAT MEF20037 007072C RAJPAL & CO MEERUT MEF20038 013955N JUNEJA SAMEER & ASSOCIATES JALANDHAR MEF20040 127309W MAHESH KUMAR MITTAL & CO SURAT MEF20042 005060S RAVI & RAGHU CHENNAI MEF20043 006877C SANJAY JHABAK & CO RAIPUR MEF20046 017362N AVISHKAR SINGHAL & ASSOCIATES LADWA MEF20048 011153N S S KATYAL & CO NEW DELHI MEF20050 004016C RAKESH K GOYAL & CO INDORE MEF20051 322499E J L CHORARIA & ASSOCIATES KOLKATA MEF20052 002578S PARKEA & CO BALLARI MEF20053 009118N RAJEEV CHOWDHARY & CO NEW -

Sakthy Academy Coimbatore

Sakthy Academy Coimbatore Bharat Ratna Award: List of recipients Year Laureates Brief Description 1954 C. Rajagopalachari An Indian independence activist, statesman, and lawyer, Rajagopalachari was the only Indian and last Governor-General of independent India. He was Chief Minister of Madras Presidency (1937–39) and Madras State (1952–54); and founder of Indian political party Swatantra Party. Sarvepalli He served as India's first Vice- Radhakrishnan President (1952–62) and second President (1962–67). Since 1962, his birthday on 5 September is observed as "Teachers' Day" in India. C. V. Raman Widely known for his work on the scattering of light and the discovery of the effect, better known as "Raman scattering", Raman mainly worked in the field of atomic physics and electromagnetism and was presented Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930. 1955 Bhagwan Das Independence activist, philosopher, and educationist, and co-founder of Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapithand worked with Madan Mohan Malaviya for the foundation of Banaras Hindu University. M. Visvesvaraya Civil engineer, statesman, and Diwan of Mysore (1912–18), was a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. His birthday, 15 September, is observed as "Engineer's Day" in India. Jawaharlal Nehru Independence activist and author, Nehru is the first and the longest-serving Prime Minister of India (1947–64). 1957 Govind Ballabh Pant Independence activist Pant was premier of United Provinces (1937–39, 1946–50) and first Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh (1950– 54). He served as Union Home Minister from 1955–61. 1958 Dhondo Keshav Karve Social reformer and educator, Karve is widely known for his works related to woman education and remarriage of Hindu widows. -

Erospace & Defence Eview

I/2011 ARerospace &Defence eview Tejas LCA attains IOC The M-MRCA stakes Fifth generation jet fighters Air Dominance Arming the M-MRCA SPECIAL ISSUE CFM I/2011 I/2011 Aerospace &Defence Review FGFA (now called the PMF). The ‘Glorious Wake, Vibrant Future’ Chinese have surprised the world In this Indian Navy section Tejas LCA attains IOC with maiden flight of their J-20 next 110 are excerpts from the speech The M-MRCA stakes generation fighter. of Admiral Nirmal Verma Fifth generation jet fighters on building a 21st Century Navy. Air Dominance Arming the M-MRCA Along with force modernisation and Celebrating the Centenary operational capability enhancement, of Aviation in India : 1910-2010 Tejas LCA attains IOC is the need to maintain a high tempo AERO INDIA 2011 Special Section on Aero India 2011 SPECIAL ISSUE This ‘good news story’ is written of operations. In a related article, 32 by Air Marshal Philip Rajkumar, Vice Admiral A K Singh looks at the design imperatives on building the Cover : The Tejas LCA limited series production–2 directly involved with the LCA (KH-2012), fitted with a pair of R-73 CCMs programme for nine years and exactly Indian Navy’s super aircraft carrier, (photo from National Flight Test Centre) 10 years after first flight of the first while Vice Admiral Anup Singh gives ‘a wake-up call’ on India’s untapped technology demonstrator (TD-1). This maritime wealth. was on eve of the function for ‘Initial EDITORIAL PANEL Operational Clearance’ on 10 January MANAGING EDITOR 2011. The daunting technological and Vikramjit -

Dr. Prahalad Rao Visit.Cdr

Sahyadri Center for Social Innovation - SCSI Inaugurated by Ex-DRDO Chief and former President Dr. Kalam's associate Padmashri Dr. Prahlada Rama Rao TM SAHYADRI th 5September SAHYADRI 2015 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT MANGALURU TM SAHYADRI SAHYADRI COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT MANGALURU You are cordially invited to the inaugural function of Sahyadri Center for Social Innovation Inauguration by Padmashri Dr. Prahlada Rama Rao Advisor, S-VYASA Deemed University Former Vice Chancellor, Defence Institute of Advanced Technology Former Director, Defence Research and Development Laboratory Time: 10.00 am - Date: Saturday, 5th September, 2015 Venue: Sahyadri Hall, Ground Floor Dr. C. Ranganathaiah Dr. U. M. Bhushi Director, Research Principal Staff and Students Sahyadri Campus, Mangaluru www.sahyadri.edu.in Invitation and Welcome Banner TM Ex-DRDO Chief SAHYADRI SAHYADRI COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT and MANGALURU former President Dr. Kalam's associate Welcomes Padmashri Dr. Prahlada Rama Rao Padmashri Dr. Prahlada Rama Rao Advisor, S-VYASA Deemed University Former Vice Chancellor Inaugurated Defence Institute of Advanced Technology Former Director Sahyadri Center for Social Innovation Defence Research and Development Laboratory at Sahyadri Campus Inaugural Function of Sahyadri Center for Social Innovation Padmashri Dr. Prahlada Rama Rao, Former Engineering, Bangalore University. Vice Chancellor of Defence Institute of Subsequently he got his Master's Degree in Advanced Technology and Former Director of Aeronautical Engineering Department from Defence Research and Development IISc., Bangalore, with specialization in Rockets Organization (DRDO) Dr. Prahlada is one of the and Missile Systems and Ph.D. in Mechanical prominent Scientists associated with Former Engineering from Jawaharlal Nehru President, Dr A.P.J Abdul Kalam in designing Technological University, Hyderabad. -

Annual Report 2016-17

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 (Approved by AICTE, New Delhi; Affiliated to JNTUA, Anantapur; Accredited by NBA; NAAC ‘A’ Grade) Sree Sainath Nagar, Tirupati – 517 102, A.P. Sree Vidyanikethan Engineering College (Autonomous) Annual Report 2016-17 1 Chairman’s Message Sree Vidyanikethan has been truly reflecting the academic excellence since 1992, when the first brick was laid for the noble cause of imparting quality education to one and all. Thousands of students and parents have started banking their trust with us. Over years, the stature and commitment of Sree Vidyanikethan Educational Trust (SVET) touched higher levels with rapid expansion in all vital fields of professional education. Today, SVET sponsors the following institutions 1) Sree Vidyanikethan International Schools 2) Sree Vidyanikethan Engineering College 3) Sree Vidyanikethan College of Pharmacy 4) Sree Vidyanikethan College of Nursing 5) Sree Vidyanikethan Degree College 6) Sree Vidyanikethan Institute of Management The major strengths of Sree Vidyanikethan Educational Institutions are Competent faculty, contemporary Learning and computing resources, modern infrastructure for learning, training and research in science, technology and engineering, pharmacy, management and nursing and student campus placements in several companies of global reputation. Above all, I always believe in the adage – Strong mind in a strong body. Hence, maximum importance is given to encourage sports and games, culturals and community activities in Sree Vidyanikethan for a wholesome personality of our students. I wish that the Trust Institutions will foster student development with values and discipline and make this a world-class university in near future. M. MOHAN BABU Sree Vidyanikethan Engineering College (Autonomous) Annual Report 2016-17 2 CEO’s Message Sree Vidyanikethan Educational Institutions stands for academic excellence and education of the whole person beyond the curriculum, within a framework of ethical, disciplined, student centric teaching. -

Going from Strength to Strength

www.aeromag.in July - August 2011 Vol : V Issue : 4 AeromagAsia DRDO Going from strength to strength A Publication in Association with the Society of Indian Aerospace Technologies & Industries (SIATI) Reliable IS THE LACK OF A SYSTEMS INTEGRATOR GIVING YOU^ A MIGRAINE Harness Captronics’ Expertise & Experience in System Integration! At Captronic Systems we make the leap from SAYING TO DOING AEROSPACE TIME IS MONEY. GET MORE OF BOT H . DEFENCE AUTOMOTIVE UNIT UNDER TEST NUCLEAR POWER MANUFACTURING WHO ARE WE A dynamic Systems Integrator, Captronic Systems Pvt Ltd started in 1999 as the bridge between Technology & Application. We specialize in the design and development of custom ATE’s with over 450 ATE’s installed worldwide, six branch oces in India and two overseas, namely UAE & USA. Over 80 LabVIEW certied engineers. WHAT DO WE DO Make a lot more parts in a lot less time with a high-performance We provide Eective, Ecient, Enterprising and Economic Solutions for Haas Drill/Tap Center. The DT-1 swaps tools in 0.8 seconds, and its all your System Integrator needs in the areas of AEROSPACE, DEFENCE, 12,000-rpm spindle allows rigid tapping to 5000 rpm, with up to 4-times AUTOMOTIVE, MANUFACTURING, NUCLEAR and POWER SECTOR retract speed. And, 2400 ipm rapids and 1 G accelerations combine to reduce cycle times even further. All this – for a great price. Typical Haas Ingenuity. Haas Automation CERTIFIED SELECT ALLIANCE PARTNER Simple. Innovation. AUTOMATION & TEST EQUIPMENT SPECIALISTS Haas Factory Outlet – India locations NORTH, WEST AND EAST -

Annual Report 14-15

N ATIONAL I NSTITUTE OF A DVANCED S NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES TUDIES Bangalore, India ANNUAL REPORT 2016 – 2017 A NNUAL R EPORT 2016 - 2017 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Indian Institute of Science Campus, Bangalore - 560 012 Tel: 080 2218 5000, Fax: 2218 5028 E-mail: [email protected] NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Bengaluru, India ANNUAL REPORT 2016 - 2017 JRD Tata Founding Chairman The Vision and Mission of NIAS To integrate the findings of scholarship in the natural and social sciences with technology and the arts through multi-disciplinary research on the complex issues that face Indian and global society. To assist in the creation of new leadership with broad horizons in all sectors of society by disseminating the conclusions of such research through appropriate publications and courses as well as dialogues with leaders and the public. TABLE OF CONTENTS From the Director 5 School of Conflict and Security Studies 10 School of Humanities 30 School of Natural Sciences and Engineering 51 School of Social Sciences 72 Invited Visiting Chair Professors 101 NIAS and Intra-Institutional National and International Collaborations 105 BRICS Conclave 107 Training Programmes 108 Doctoral Programme 114 Annual Memorial Lectures 117 Public Programmes 118 Wednesday Discussion Meetings 125 Associates’ Programme 130 Literary, Arts and Heritage Forum 131 Library 132 Publications 133 Administration 147 Financial Reports 152 NIAS Council of Management 157 NIAS Society 158 NIAS Staff 159 NIAS Adjunct Professors and Adjunct Faculty 160 CONTENTS FROM THE DIRECTOR It is with delight that I write some of the thoughts for the annual report of National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), 2016-2017. -

Of ^Ngtrasrmg

(SlttMatt "^attowal JVcaitem]j of ^ngtrasrmg THE YEAR BOOK 2021 CALENDAR 2021 M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 121314 8 9 10 11 12 1314 11 12 13 14 15 1617 15 16 17 18 1920 21 15 16 17 18 1920 21 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 31 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 6 7 8 910 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 141516 14 15 16 17 181920 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 30 31 1 1 2 3 4 5 5 6 7 8 910 11 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 1011 12 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 131415 13 14 15 16 171819 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 26 27 28 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 M T W T F S S M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 121314 6 7 8 9 1011 12 11 12 13 14 151617 15 16 17 18 1920 21 13 14 15 16 171819 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 27 28 29 30 31 (3lttbtatt ^cabmtjg of ^Ettgtmermg THE YEAR BOOK 2021 The Indian National Academy of Engineering (INAE), established in 1987 as a Society under the Societies Registration Act, is an autonomous professional body. -

Twelfth Annual Convocation

TWELFTH ANNUAL CONVOCATION November 15, 2014 National Institute of Technology Karnataka, Surathkal (An Institute of National Importance established by an Act of Parliament) Mangaluru – 575 025, India www.nitk.ac.in National Institute of Technology Karnataka, Surathkal Mangaluru - 575 025, India Board of Governors Ms. Vanitha Narayanan, Honourable Chairperson Managing Director, IBM India Private Limited, No.12, Subramanya Arcade, Bannerghatta Main Road, Bengaluru, India - 560 029 Members Amarjeet Sinha IAS, Sri Yogendra Tripathi, Additional Secretary (T) Joint Secretary and Financial Advisor, Ministry of Human Resource Ministry of Human Resource Development, Development Dept. of Higher Education, Technical Dept. of Higher Education, Technical Education Bureau Education Bureau Shastri Bhavan, New Delhi – 110 001 Shastri Bhavan, New Delhi – 110 001 yogendra[dot]tripathi[at]nic[dot]in email: asinha[dot]edu[at]nic[dot]in, 011- 23070668(Fax) 011- 23387797 (Tel-Fax) Prof. Swapan Bhattacharya, Dr. Badekai Ramachandra Bhat, Director, Professor, NITK, Surathakal Department of Chemistry NITK, Surathkal. Sri Vinay Kumar, Sri. K Ravindranath Associate Professor, Secretary Dept. of Computer Science & Engineering, Registrar i/c N.I.T.K, Surathkal. N.I.T.K, Surathkal Editorial Team M B Saidutta U. Sripati Lakshman Nandagiri Varghese George Shashikantha Gaurav Chowdhury Iranna Shettar TWELFTH ANNUAL CONVOCATION Twelfth ANNUAL CONVOCATION Welcome Address and Institute Report Prof. Swapan Bhattacharya Director, NITK, Surathkal Esteemed Chief Guest of the Convocation function, Dr. Satish K. Tripathi , Respected Ms. Vanitha Narayanan, Chairperson, Board of Governors of NITK, members of the BOG, members of the Senate, degree recipients, distinguished guests, proud Parents, members of the media and my dear colleagues on the faculty and staff of NITK, it is my proud privilege to welcome you all to this Twelfth Annual Convocation of our Institute.