Market Structure and Liquidity on the Tokyo Stock Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global IPO Trends Report Is Released Every Quarter and Looks at the IPO Markets, Trends and Outlook for the Americas, Asia-Pacific and EMEIA Regions

When will the economy catch up with the capital markets? Global IPO trends: Q3 2020 ey.com/ipo/trends #IPOreport Contents Global IPO market 3 Americas 10 Asia-Pacific 15 Europe, Middle East, India and Africa 23 Appendix 29 About this report EY Global IPO trends report is released every quarter and looks at the IPO markets, trends and outlook for the Americas, Asia-Pacific and EMEIA regions. The current report provides insights, facts and figures on the IPO market for the first nine months of 2020* and analyzes the implications for companies planning to go public in the short and medium term. You will find this report at the EY Global IPO website, and you can subscribe to receive it every quarter. You can also follow the report on social media: via Twitter and LinkedIn using #IPOreport *The first nine months of 2020 cover completed IPOs from 1 January 2020 to 30 September 2020. All values are US$ unless otherwise noted. Subscribe to EY Quarterly IPO trends reports Get the latest IPO analysis direct to your inbox. GlobalGlobal IPO IPO trends: trends: Q3Q3 20202020 || Page 2 Global IPO market Liquidity fuels IPOs amidst global GDP contraction “Although the market sentiments can be fragile, the scene is set for a busy last quarter to end a turbulent 2020 that has seen some stellar IPO performance. The US presidential election, as well as the China-US relationship post-election, will be key considerations in future cross-border IPO activities among the world’s leading stock exchanges. Despite the uncertainties, companies and sectors that have adapted and excelled in the ‘new normal’ should continue to attract IPO investors. -

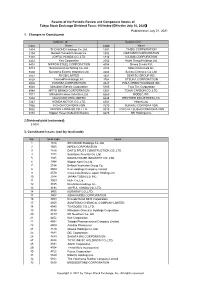

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

Feb. 22, 2021 Listing Department Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. Outline

(Reference Translation) Feb. 22, 2021 Listing Department Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. Outline of Initial Listing Issue Company Name G-NEXT Inc. Scheduled Listing Date Mar. 25 2021 Market Section Mothers Current Listed Market N/A Name and Title of YOKOJI Yusuke, Representative Director Representative Address of Main Office 4-7-1 Iidabashi, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo, 102-0072 Tel. +81-3-5962-5170 (Closest Point of Contact) (Same as above) Home Page https://www.gnext.co.jp/ Date of Incorporation Jul. 12, 2001 Description of Business Developing and providing "Discoveriez", a customer relationship software Category of Industry / Information & Communication / 4179 (ISIN JP3386760007) Code Authorized Total No. of 10,750,000 shares Shares to be Issued No. of Issued Shares 3,732,200 shares (As of Feb. 22, 2021) No. of Issued Shares 4,082,200 shares (incl. treasury shares) (Note 1) The number includes newly issued shares issued through the at the Time of Listing public offering. (Note 2) The number could increase as a result of the exercise of the share options. Capital JPY 396,137 thousand (As of Feb. 22, 2021) No. of Shares per Share 100 shares Unit Business Year From Apr. 1 to Mar. 31 of the following year General Shareholders In June Meeting Record Date Mar. 31 Record Date of Surplus Sep. 30 and Mar. 31 Dividend Transfer Agent Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Limited Auditor TOHO Audit Corporation Managing Trading SMBC Nikko Securities Inc. Participant -1- © 2021 Tokyo Stock Exchange, Inc. All rights reserved. DISCLAIMER: This translation may be used only for reference purposes. This English version is not an official translation of the original Japanese document. -

Price and Volume in the Tokyo Stock Exchange : an Exploratory Study

rcsffinz , i. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN BOOKSTACKS ]^ *- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/pricevolumeintok1573tsey BEBR FACULTY WORKING PAPER NO. 89-157:5 • '-/w Trice and \ olume in the rokyo Stock Exchange: An Exploratory Study The Library of the AUG 1 1989 University cl Hiinofc of Urbana-Champalgn V. K. Tse . BEBR FACULTY WORKING PAPER NO. 89-1573 College of Commerce and Business Administration University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign May 1989 Price and Volume in the Tokyo Stock Exchange An Exploratory Study Y. K. Tse, Visiting Scholar Department of Economics This paper was written when I was visiting the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign. I thank Josef Lakonishok for stimulation and inspiration Abstract: In this paper, we consider the unconditional distributions of market return and trading volume in the Tokyo Stock Exchange. We also examine the relationship between price changes and trading volumes. The problems considered are directed by findings in the U.S. market, with a view to ascertain similarities and differences. Daily market returns exhibit intra-week periodicity. Returns over daily, weekly and monthly intervals are negativelv skewed and leptokurtLc. While daily returns are slightly positively autocorre- lated, the autocorrelations for weekly and monthly returns are statistically insignificant. There is evidence against the stable Paretian hypothesis for market returns; and the empirical results are in support of market returns following a low order mixture of normal distribution. Trading volume is highly positively autocorrelated. This suggests that trading volume is not a good proxy for information. -

Capital Market Theory, Mandatory Disclosure, and Price Discovery Lawrence A

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 51 | Issue 3 Article 3 Summer 6-1-1994 Capital Market Theory, Mandatory Disclosure, and Price Discovery Lawrence A. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence A. Cunningham, Capital Market Theory, Mandatory Disclosure, and Price Discovery, 51 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 843 (1994), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol51/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Capital Market Theory, Mandatory Disclosure, and Price Discovery Lawrence A. Cunningham* L Introduction The once-venerable "efficient capital market hypothesis" (ECMH) crashed along with world capital markets in October 1987, but its resilience has nearly matched the resilience of those markets. Despite another market break in 1989, for example, the ECMH has continued to be reflexively heralded by numerous corporate and securities law scholars as an accurate account of public capital market behavior. Together with overwhelming evidence of excessive market volatility, however, these catastrophic market breaks revealed instinct infirmities m the ECMH that could hardly be shrugged off as mere anomalies. In response to the ECMH's eroding descriptive and prescriptive power, capital market theorists found in noise theory an auxiliary explanation for these otherwise inexplicable catastrophes. -

Series 6 Kaplan Financial Education

The Exam Series 6 • 100 questions (plus 10 experimental) Kaplan Financial • 2¼ hours Education • 70% to pass ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 1 ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 2 Session One Securities Markets, Investment Securities and Corporate Securities, and Economic Capitalization Factors ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 3 ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 4 Securities and Corporate Securities and Corporate Capitalization Capitalization A. Issue stock B. Issue debt 1. Ownership (equity) 1. Bonds, notes 2. Limited liability 2. Holder of note or bond is creditor of corporation 3. Conservative for issuer a. Senior to equity securities in the event of liquidation Public 3. Conservative for investor Public ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 5 ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 6 1 Common Stock A. Characteristics 1. All corporations issue common stock Common Stock 2. Most junior security a. Has a residual claim to assets if company goes out of business or liquidates 3. Purchased for a. Growth b. Income c. Growth and income ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 7 ©2015 Kaplan University School of Professional and Continuing Education 8 Common Stock (Dates) Common Stock (continued) B. Dates 3. Regulation T—FRB 1. Trade date a. Credit extended from broker/dealer to customer 2. Settlement date b. Two business days after settlement date a. Cash—trade date and settlement date on same c. Time extension day 1.) FINRA or Exchange b. Regular way—three business days d. -

Equities: Characteristics and Markets I. Reading. A. BKM Chapter 3

Lecture 3 Foundations of Finance Lecture 3: Equities: Characteristics and Markets I. Reading. A. BKM Chapter 3: Sections 3.2-3.5 and 3.8 are the most closely related to the material covered here. II. Terminology. A. Bid Price: 1. Price at which an intermediary is ready to purchase the security. 2. Price received by a seller. B. Asked Price: 1. Price at which an intermediary is ready to sell the security. 2. Price paid by a buyer. C. Spread: 1. Difference between bid and asked prices. 2. Bid price is lower than the asked price. 3. Spread is the intermediary’s profit. Investor Price Intermediary Buy Asked Sell Sell Bid Buy 1 Lecture 3 Foundations of Finance III. Secondary Stock Markets in the U.S.. A. Exchanges. 1. National: a. NYSE: largest. b. AMEX. 2. Regional: several. 3. Some stocks trade both on the NYSE and on regional exchanges. 4. Most exchanges have listing requirements that a stock has to satisfy. 5. Only members of an exchange can trade on the exchange. 6. Exchange members execute trades for investors and receive commission. B. Over-the-Counter Market. 1. National Association of Securities Dealers-National Market System (NASD-NMS) a. the major over-the-counter market. b. utilizes an automated quotations system (NASDAQ) which computer-links dealers (market makers). c. dealers: (1) maintain an inventory of selected stocks; and, (2) stand ready to buy a certain number of shares of stock at their stated bid prices and ready to sell at their stated asked prices. (a) pre-Jan 21, 1997, up to 1000 shares. -

Nasdaq Trader Manual

Nasdaq Trader Manual Notice: This manual is in no way intended to be a substitution for, or relied upon in lieu of, the rules contained in the NASD Manual. The design and information contained in this manual are owned by The Nasdaq Stock Market, Inc. (Nasdaq), or one of its affiliates, the National Association of Securities Dealers, Inc. (NASD), NASD Regulation, Inc. (NASDR), Nasdaq International Ltd., or Nasdaq International Market Initiatives, Ltd. (NIMI). The information contained in the manual may be used and copied for internal business purposes only. All copies must bear this permission notice and the following copyright citation on the first page: “Copyright © 1998, The Nasdaq Stock Market, Inc. All rights reserved.” The information may not other- wise be used (not copied, performed, distributed, rented, sublicensed, altered, stored for subsequent use, or otherwise used in whole or in part, in any manner) without Nasdaq’s prior written consent except to the extent that such use constitutes “fair use” under the “Copyright Act” of 1976 (17 U.S.C. Section 107), as amended. In addition, the information may not be taken out of context or presented in a unfair, misleading or discriminating manner. THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN IS PROVIDED ONLY FOR THE PURPOSE OF PRO- VIDING GENERAL GUIDANCE AS TO THE APPLICATION OF PARTICULAR NASD RULES. ALL USERS, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO, MEMBERS, ASSOCIATED PERSONS AND THEIR COUNSEL SHOULD CONSIDER THE NEED FOR FURTHER GUIDANCE AS TO THE APPLICATION OF NASD RULES TO THEIR OWN UNIQUE CIRCUMSTANCES. NO STATE- MENTS ARE INTENDED AS EXPRESS WARRANTIES. ALL INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. -

The Structure of the Securities Market–Past and Future, 41 Fordham L

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1972 The trS ucture of the Securities Market–Past and Future William K.S. Wang UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Thomas A. Russo Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Securities Law Commons Recommended Citation William K.S. Wang and Thomas A. Russo, The Structure of the Securities Market–Past and Future, 41 Fordham L. Rev. 1 (1972). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/773 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Wang William Author: William K.S. Wang Source: Fordham Law Review Citation: 41 Fordham L. Rev. 1 (1972). Title: The Structure of the Securities Market — Past and Future Originally published in FORDHAM LAW REVIEW. This article is reprinted with permission from FORDHAM LAW REVIEW and Fordham University School of Law. THE STRUCTURE OF THE SECURITIES MARIET-PAST AND FUTURE THOMAS A. RUSSO AND WILLIAM K. S. WANG* I. INTRODUCTION ITHE securities industry today faces numerous changes that may dra- matically alter its methods of doing business. The traditional domi- nance of the New York Stock Exchange' has been challenged by new markets and new market systems, and to some extent by the determina- tion of Congress and the SEC to make the securities industry more effi- cient and more responsive to the needs of the general public. -

Providing the Regulatory Framework for Fair, Efficient and Dynamic European Securities Markets

ABOUT CEPS Founded in 1983, the Centre for European Policy Studies is an independent policy research institute dedicated to producing sound policy research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges fac- Competition, ing Europe today. Funding is obtained from membership fees, contributions from official institutions (European Commission, other international and multilateral institutions, and national bodies), foun- dation grants, project research, conferences fees and publication sales. GOALS •To achieve high standards of academic excellence and maintain unqualified independence. Fragmentation •To provide a forum for discussion among all stakeholders in the European policy process. •To build collaborative networks of researchers, policy-makers and business across the whole of Europe. •To disseminate our findings and views through a regular flow of publications and public events. ASSETS AND ACHIEVEMENTS • Complete independence to set its own priorities and freedom from any outside influence. and Transparency • Authoritative research by an international staff with a demonstrated capability to analyse policy ques- tions and anticipate trends well before they become topics of general public discussion. • Formation of seven different research networks, comprising some 140 research institutes from throughout Europe and beyond, to complement and consolidate our research expertise and to great- Providing the Regulatory Framework ly extend our reach in a wide range of areas from agricultural and security policy to climate change, justice and home affairs and economic analysis. • An extensive network of external collaborators, including some 35 senior associates with extensive working experience in EU affairs. for Fair, Efficient and Dynamic PROGRAMME STRUCTURE CEPS is a place where creative and authoritative specialists reflect and comment on the problems and European Securities Markets opportunities facing Europe today. -

How Important Is Liquidity Risk for Sovereign Bond Risk Premia? Evidence from the London Stock Exchange by Ron Alquist

Working Paper/Document de travail 2008-47 How Important Is Liquidity Risk for Sovereign Bond Risk Premia? Evidence from the London Stock Exchange by Ron Alquist www.bank-banque-canada.ca Bank of Canada Working Paper 2008-47 December 2008 How Important Is Liquidity Risk for Sovereign Bond Risk Premia? Evidence from the London Stock Exchange by Ron Alquist International Economic Analysis Department Bank of Canada Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0G9 [email protected] Bank of Canada working papers are theoretical or empirical works-in-progress on subjects in economics and finance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank of Canada. ISSN 1701-9397 © 2008 Bank of Canada Acknowledgements I would like to thank my colleagues in the International Department at the Bank of Canada, seminar participants at the University of Saskatchewan, Laura Beny, Ben Chabot, Lutz Kilian, Linda Tesar, Marc Weidenmier, and Kathy Yuan for their comments. Brian DePratto, Maggie Jim, and Golbahar Kazemian provided first-rate research assistance. ii Abstract This paper uses the framework of arbitrage-pricing theory to study the relationship between liquidity risk and sovereign bond risk premia. The London Stock Exchange in the late 19th century is an ideal laboratory in which to test the proposition that liquidity risk affects the price of sovereign debt. This period was the last time that the debt of a heterogeneous set of countries was traded in a centralized location and that a sufficiently long time series of observable bond prices are available to conduct asset-pricing tests. -

Your Exchange of Choice Overview of JPX Who We Are

Your Exchange of Choice Overview of JPX Who we are... Japan Exchange Group, Inc. (JPX) was formed through the merger between Tokyo Stock Exchange Group and Osaka Securities Exchange in January 2013. In 1878, soon after the Meiji Restoration, Eiichi Shibusawa, who is known as the father of capitalism in Japan, established Tokyo Stock Exchange. That same year, Tomoatsu Godai, a businessman who was instrumental in the economic development of Osaka, established Osaka Stock Exchange. This year marks the 140th anniversary of their founding. JPX has inherited the will of both Eiichi Shibusawa and Tomoatsu Godai as the pioneers of capitalism in modern Japan and is determined to contribute to drive sustainable growth of the Japanese economy. Contents Strategies for Overview of JPX Creating Value 2 Corporate Philosophy and Creed 14 Message from the CEO 3 The Role of Exchange Markets 18 Financial Policies 4 Business Model 19 IT Master Plan 6 Creating Value at JPX 20 Core Initiatives 8 JPX History 20 Satisfying Diverse Investor Needs and Encouraging Medium- to Long-Term Asset 10 Five Years since the Birth of JPX - Building Milestone Developments 21 Supporting Listed Companies in Enhancing Corporate Value 12 FY2017 Highlights 22 Fulfilling Social Mission by Reinforcing Market Infrastructure 23 Creating New Fields of Exchange Business Editorial Policy Contributing to realizing an affluent society by promoting sustainable development of the market lies at the heart of JPX's corporate philosophy. We believe that our efforts to realize this corporate philosophy will enable us to both create sustainable value and fulfill our corporate social responsibility. Our goal in publishing this JPX Report 2018 is to provide readers with a deeper understanding of this idea and our initiatives in business activities.