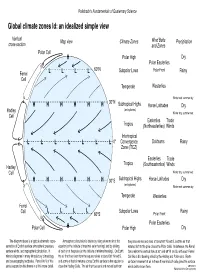

Global Climate Zones Ia: Building an Idealized Simple View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Concepts in Oceanography

Chapter 1 XA0101461 BASIC CONCEPTS IN OCEANOGRAPHY L.F. SMALL College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, United States of America Abstract Basic concepts in oceanography include major wind patterns that drive ocean currents, and the effects that the earth's rotation, positions of land masses, and temperature and salinity have on oceanic circulation and hence global distribution of radioactivity. Special attention is given to coastal and near-coastal processes such as upwelling, tidal effects, and small-scale processes, as radionuclide distributions are currently most associated with coastal regions. 1.1. INTRODUCTION Introductory information on ocean currents, on ocean and coastal processes, and on major systems that drive the ocean currents are important to an understanding of the temporal and spatial distributions of radionuclides in the world ocean. 1.2. GLOBAL PROCESSES 1.2.1 Global Wind Patterns and Ocean Currents The wind systems that drive aerosols and atmospheric radioactivity around the globe eventually deposit a lot of those materials in the oceans or in rivers. The winds also are largely responsible for driving the surface circulation of the world ocean, and thus help redistribute materials over the ocean's surface. The major wind systems are the Trade Winds in equatorial latitudes, and the Westerly Wind Systems that drive circulation in the north and south temperate and sub-polar regions (Fig. 1). It is no surprise that major circulations of surface currents have basically the same patterns as the winds that drive them (Fig. 2). Note that the Trade Wind System drives an Equatorial Current-Countercurrent system, for example. -

11 General Circulation

Copyright © 2017 by Roland Stull. Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science. v1.02 “Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science” by Roland Stull is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. View this license at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-sa/4.0/ . This work is available at https://www.eoas.ubc.ca/books/Practical_Meteorology/ 11 GENERAL CIRCULATION Contents A spatial imbalance between radiative inputs and outputs exists for the earth-ocean-atmosphere 11.1. Key Terms 330 system. The earth loses energy at all latitudes due 11.2. A Simple Description of the Global Circulation 330 to outgoing infrared (IR) radiation. Near the trop- 11.2.1. Near the Surface 330 ics, more solar radiation enters than IR leaves, hence 11.2.2. Upper-troposphere 331 there is a net input of radiative energy. Near Earth’s 11.2.3. Vertical Circulations 332 poles, incoming solar radiation is too weak to totally 11.2.4. Monsoonal Circulations 333 offset the IR cooling, allowing a net loss of energy. 11.3. Radiative Differential Heating 334 The result is differential heating, creating warm 11.3.1. North-South Temperature Gradient 335 equatorial air and cold polar air (Fig. 11.1a). 11.3.2. Global Radiation Budgets 336 This imbalance drives the global-scale general 11.3.3. Radiative Forcing by Latitude Belt 338 circulation of winds. Such a circulation is a fluid- 11.3.4. General Circulation Heat Transport 338 dynamical analogy to Le Chatelier’s Principle of 11.4. -

Horse Latitudes

HORSE LATITUDES Introduction The Horse Latitudes are located between latitude 30 and latitude 35 north and south of the equator. The region lies in an area where there is a ridge of high pressure that circles the Earth. The ridge of high pressure is also called a subtropical high. Wind currents on Earth, USGS Sailing ships in these latitudes The area between these latitudes has little precipitation. It has variable winds. Sailing ships sometimes while traveling to distant shores would have the winds die down and the area would be calm for days before the winds increased. Desert formation on Earth These warm dry conditions lead to many well known deserts. In the Northern Hemisphere deserts that lie in this subtropical high included the Sahara Desert in Africa and the southwestern deserts of the United States and Mexico. The Atacama Desert, the Kalahari Desert and the Australian Desert are all located in the southern Horse Latitudes. Two explanations for the name There are two explanations of how these areas were named. This first explanation is well documented. Sailors would receive an advance in pay before they stated on a long voyage which was spent quickly leaving the sailors without money for several months while aboard ship. Sailors work off debt When the sailors had worked long enough to again earn enough to be paid they would parade around the deck with a straw-stuffed effigy of a horse. After the parade the sailors would throw the straw horse overboard. Second explanation about horses The second explanation is not well documented. -

Weather and Climate Science 4-H-1024-W

4-H-1024-W LEVEL 2 WEATHER AND CLIMATE SCIENCE 4-H-1024-W CONTENTS Air Pressure Carbon Footprints Cloud Formation Cloud Types Cold Fronts Earth’s Rotation Global Winds The Greenhouse Effect Humidity Hurricanes Making Weather Instruments Mini-Tornado Out of the Dust Seasons Using Weather Instruments to Collect Data NGSS indicates the Next Generation Science Standards for each activity. See www. nextgenscience.org/next-generation-science- standards for more information. Reference in this publication to any specific commercial product, process, or service, or the use of any trade, firm, or corporation name See Purdue Extension’s Education Store, is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute an www.edustore.purdue.edu, for additional endorsement, recommendation, or certification of any kind by Purdue Extension. Persons using such products assume responsibility for their resources on many of the topics covered in the use in accordance with current directions of the manufacturer. 4-H manuals. PURDUE EXTENSION 4-H-1024-W GLOBAL WINDS How do the sun’s energy and earth’s rotation combine to create global wind patterns? While we may experience winds blowing GLOBAL WINDS INFORMATION from any direction on any given day, the Air that moves across the surface of earth is called weather systems in the Midwest usually wind. The sun heats the earth’s surface, which warms travel from west to east. People in Indiana can look the air above it. Areas near the equator receive the at Illinois weather to get an idea of what to expect most direct sunlight and warming. The North and the next day. -

Dicionarioct.Pdf

McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Earth Science Second Edition McGraw-Hill New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be repro- duced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-141798-2 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-141045-7 All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw- Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decom- pile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Download Demo

For DLP, Current Affairs Magazine & Test Series related regular updates, follow us on www.facebook.com/drishtithevisionfoundation www.twitter.com/drishtiias CONTENTS UNIT-I : GEOMORPHOLOGY 1. Introduction to Geography 3-5 2. Origin of Universe, Earth & Life 6-11 3. Our Earth 12-29 4. Rocks & Minerals 30-32 5. Weathering, Mass Movement & Erosion 33-40 6. Landforms 41-51 7. Soil 52-62 UNIT-II : CLIMATOLOGY 8. Weather & Climate 65-67 9. Composition & Structure of Atmosphere 68-71 10. Distribution of Temperature & Heat Budget 72-80 11. Pressure & Wind Systems 81-100 12. Condensation & Precipitation 101-108 13. Classification of Climate 109-114 UNIT-III : OCEANOGRAPHY 14. Oceans 117-130 15. Oceanic Resources 131-136 UNIT-IV : HUMAN & ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY 16. Population 139-154 17. Human Development 155-160 18. Settlement & Migration 161-173 19. Agriculture 174-201 20. Resources of the World 202-224 21. Location of Industries 225-247 22. Transport 248-254 Previous Years’ UPSC Questions (Solved) 255-261 Practice Questions 262 Pressure & Wind Systems 11 Chapter The weight of a column of air contained in a unit area from the mean sea level to the top of the atmosphere is called the air or atmospheric pressure. The atmospheric pressure is expressed in units of millibar. At sea level the average atmospheric pressure is 1,013.2 millibar. Due to gravity, the air at the surface is denser and hence has higher pressure. Air pressure is measured with the help of a mercury barometer or the aneroid barometer. The pressure decreases with height. At any elevation it varies from place to place and its variation is the primary cause of air motion, i.e. -

Use of Synthetic Aperture Radar in Finescale Surface Analysis of Synoptic-Scale Fronts at Sea

JUNE 2005 YOUNG ET AL. 311 Use of Synthetic Aperture Radar in Finescale Surface Analysis of Synoptic-Scale Fronts at Sea G. S. YOUNG Department of Meteorology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania T. D. SIKORA Department of Oceanography, United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland N. S. WINSTEAD Applied Physics Laboratory, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland (Manuscript received 8 March 2004, in final form 6 December 2004) ABSTRACT The viability of synthetic aperture radar (SAR) as a tool for finescale marine meteorological surface analyses of synoptic-scale fronts is demonstrated. In particular, it is shown that SAR can reveal the presence of, and the mesoscale and microscale substructures associated with, synoptic-scale cold fronts, warm fronts, occluded fronts, and secluded fronts. The basis for these findings is the analysis of some 6000 RADARSAT-1 SAR images from the Gulf of Alaska and from off the east coast of North America. This analysis yielded 158 cases of well-defined frontal signatures: 22 warm fronts, 37 cold fronts, 3 stationary fronts, 32 occluded fronts, and 64 secluded fronts. The potential synergies between SAR and a range of other data sources are discussed for representative fronts of each type. 1. Introduction sensor can meet all of the analyst’s needs. It is only by using the available sensors synergistically that a fine- Finescale surface analysis of synoptic-scale weather scale marine surface analysis may be prepared. Note systems is a challenging undertaking in the best of cir- C-MAN in Table 1 refers to Coastal–Marine Auto- cumstances, but has proven particularly difficult at sea mated Network. -

Global Climate Zones Id: an Idealized Simple View

Railsback's Fundamentals of Quaternary Science Global climate zones Id: an idealized simple view Vertical Map view Climate Zones Wind Belts Precipitation cross-section and Zones Polar Cell H Polar High Dry Polar Easterlies 60°N Subpolar Lows Polar Front Rainy Ferrel L L L L Cell Temperate Westerlies Winter wet; summer dry 30°N H H H H H H Subtropical Highs Horse Latitudes Dry (anticyclones) Hadley Winter dry; summer wet Cell Easterlies Trade Tropics (Northeasterlies) Winds Intertropical L L L L L L L 0° Convergence Doldrums Rainy Zone (ITCZ) Easterlies Trade Tropics (Southeasterlies) Winds Hadley Cell Winter dry; summer wet H H H H H H 30°S Subtropical Highs Horse Latitudes Dry (anticyclones) Winter wet; summer dry Temperate Westerlies Ferrel Cell L L L L Subpolar Lows Rainy 60°S Polar Front Polar Easterlies Polar Cell H Polar High Dry The diagram above is a typical schematic repre- Atmospheric circulation is driven by rising of warm air at the the poles warms and rises at about 60° N and S, and the air that sentation of Earth's surface atmospheric pressure, equator (at the latitude of maximal solar heating) and by sinking returns aloft to the pole closes the Polar Cells. In between, the Ferrel surface winds, and tropospheric circulation. It of cold air at the poles (at the latitude of minimal heating). On Earth, Cells mirror the vertical flow at 30° and 60° N and S, with each Ferrell mimics diagrams in many introductory climatology the air that has risen from the equator sinks at about 30° N and S, Cell like a ball bearing rolled by the Hadley and Polar cells. -

Barry R.G., Chorley R.J. Atmosphere, Weather and Climate (8Ed

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Atmosphere, Weather and Climate 11 12 13 14 15 16 Atmosphere, Weather and Climate is the essential I updated analysis of atmospheric composition, 17 introduction to weather processes and climatic con- weather and climate in middle latitudes, atmospheric 18 ditions around the world, their observed variability and oceanic motion, tropical weather and climate, 19 and changes, and projected future trends. Extensively and small-scale climates 20 revised and updated, this eighth edition retains its I chapter on climate variability and change has been 21 popular tried and tested structure while incorporating completely updated to take account of the findings of 22 recent advances in the field. From clear explanations the IPCC 2001 scientific assessment 23 of the basic physical and chemical principles of the 24 atmosphere, to descriptions of regional climates and I new more attractive and accessible text design 25 their changes, Atmosphere, Weather and Climate I new pedagogical features include: learning objec- 26 presents a comprehensive coverage of global meteor- tives at the beginning of each chapter and discussion 27 ology and climatology. In this new edition, the latest points at their ending, and boxes on topical subjects 28 scientific ideas are expressed in a clear, non- and twentieth-century advances in the field. 29 mathematical manner. 30 Roger G. Barry is Professor of Geography, University 31 New features include: of Colorado at Boulder, Director of the World Data 32 Center for Glaciology and a Fellow of the Cooperative 33 I new introductory chapter on the evolution and scope Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences. -

Ch. 11-13 I. Atmosphere - Layer of Gas That Surrounds the Earth

Ch. 11-13 I. Atmosphere - layer of gas that surrounds the Earth. A. Composition 1. 78% - N2 2. 21% - O2 3. 0%-4% - water vapor 4. 1% - other gases 5. Ozone - O3 - protects us from UV radiation. B. Smog - smoke and fog mixing with sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide 1. From the burning of coal, gasoline, and other fossil fuels C. solids (dust and ice) and liquids (water). II. Layers - divided according to major changes in temperature A. Troposphere - the lowest layer we live here weather occurs here 1. 75% of all atmosphere gases 2. ↓ temp. with ↑ altitude 3. Tropopause - boundary between troposphere and the next layer B. Stratosphere - 2nd layer 1. Jet stream - strong west wind. 2. Ozone (O3) - is found here. 3. ↑ temp. with ↑ altitude. 4. Stratopause - boundary between stratosphere and mesosphere. C. Mesosphere - area where meteors burn up ↓ temp. with ↑ altitude Mesopause - boundary between mesosphere and thermosphere D. Thermosphere - means "heat sphere" 1. Very thin air (1/10,000,000) of the earth's surface 2. High temperature - N2 and O2 absorb U.V. light and turn it into heat 3. Cannot measure with thermometer D1. Ionosphere - lower part of thermosphere 1. Layer of ions 2. Used for radio waves 3. When particles from the sun strike the ionosphere it causes: Auroras - northern and southern lights D2. Exosphere - layer that extends into outer space 1. Satellites orbit here III. Air pressure - the pressure that air molecules force upon an object. A. Decreases with altitude. B. Barometer - instrument that measures atmospheric pressure. (Altimeter?) C. Warm air is less dense than cold air. -

Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (Pp

Chapter 7 - Title Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (pp. 165-195) Contents • scales of motion and turbulence • local winds • the General Circulation of the atmosphere • ocean currents Wind Examples Fig. 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion. Microscale → mesoscale → synoptic scale. Scales of Motion • Microscale – e.g. chimney – Short lived ‘eddies’, chaotic motion – Timescale: minutes • Mesoscale – e.g. local winds, thunderstorms – Timescale mins/hr/days • Synoptic scale – e.g. weather maps – Timescale: days to weeks • Planetary scale – Entire earth Scales of Motion Table 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion Turbulence • Eddies : internal friction generated as laminar (smooth, steady) flow becomes irregular and turbulent • Most weather disturbances involve turbulence • 3 kinds: – Mechanical turbulence – you, buildings, etc. – Thermal turbulence – due to warm air rising and cold air sinking caused by surface heating – Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) - due to wind shear, i.e. change in wind speed and/or direction Mechanical Turbulence • Mechanical turbulence – due to flow over or around objects (mountains, buildings, etc.) Mechanical Turbulence: Wave Clouds • Flow over a mountain, generating: – Wave clouds – Rotors, bad for planes and gliders! Fig. 7.2: Mechanical turbulence - Air flowing past a mountain range creates eddies hazardous to flying. Thermal Turbulence • Thermal turbulence - essentially rising thermals of air generated by surface heating • Thermal turbulence is maximum during max surface heating - mid afternoon Questions 1. A pilot enters the weather service office and wants to know what time of the day she can expect to encounter the least turbulent winds at 760 m above central Kansas. If you were the weather forecaster, what would you tell her? 2. -

050 00 00 00 - Meteorology)

AIRLINE TRANSPORT PILOTS LICENSE (050 00 00 00 - METEOROLOGY) JAR-FCL LEARNING OBJECTIVES REMARKS REF NO 050 01 00 00 THE ATMOSPHERE 050 01 01 00 Composition, Extent, Vertical Division 050 01 01 01 Describe the vertical division of the atmosphere, based on the temperature variations with height: - List the different layers and their main qualitative characteristics - Describe the troposphere - Define tropopause - Mention the main values of the standard (ISA) atmosphere up to the tropopause - Describe the proportions of the most important gases in the air in the troposphere - Describe the variations of the height and temperature of the tropopause from the poles to the equator - Describe the breaks in the tropopause along the limits of the main air masses - Indicate the variations of the tropopause height with the seasons and the variations of atmospheric pressure - Define stratosphere - Describe the main variations with height of the composition of the air in the stratosphere - Describe the ozone layer 050 01 02 00 Temperature - Define air temperature First Issue 050-MET-1 Sep 1999 AIRLINE TRANSPORT PILOTS LICENSE (050 00 00 00 - METEOROLOGY) JAR-FCL LEARNING OBJECTIVES REMARKS REF NO - List the units of measurement of air temperature used in aviation meteorology 050 01 02 01 Vertical distribution of temperature - Mention general causes of the cooling of the air in the troposphere with increasing altitude, and of the warming of the air in the stratosphere - Distinguish between standard temperature gradient, adiabatic, and saturated adiabatic