Jubilee Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Politics of Regulation: Haussmann's Planning Practice and Badiou's

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE A Politics of Regulation: Haussmann’s Planning Practice and Badiou’s Philosophy Antoine Michel Paccoud A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Environment of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2012 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 103,470 words (including 6,232 words of footnotes, essentially the original French versions of material quoted within the text). 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with empirically determining whether a particular political sequence can be interpreted through Badiou’s philosophy. It focuses on the public works that transformed Paris in the middle of the 19th century, and more specifically on Haussmann’s planning practice. From an epistolary exchange between property owners, Haussmann and the Minister of the Interior during Haussmann’s first years as Prefect of the Seine, the thesis draws out a political event: the playing out in a singular context of an opposition over a political practice predicated on equality. -

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

PDF995, Job 6

The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country _____________________________________________________________ The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background December 2005 Protecting Wildlife for the Future The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 The Wildlife Trust for Birmingham and the Black Country gratefully acknowledges support from English Nature, Dudley MBC, Sandwell MBC, Walsall MBC and Wolverhampton City Council. This Report was compiled by: Dr Ellen Pisolkar MSc IEEM The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 3. SITES 4 3.1 Introduction 4 3.2 Birmingham 3.2.1 Edgbaston Reservoir 5 3.2.2 Moseley Bog 11 3.2.3 Queslett Quarry 17 3.2.4 Spaghetti Junction 22 3.2.5 Swanshurst Park 26 3.3 Dudley 3.3.1 Castle Hill 30 3.3.2 Doulton’s Claypit/Saltwells Wood 34 3.3.3 Fens Pools 44 3.4 Sandwell 3.4.1 Darby’s Hill Rd and Darby’s Hill Quarry 50 3.4.2 Sandwell Valley 54 3.4.3 Sheepwash Urban Park 63 3.5 Walsall 3.5.1 Moorcroft Wood 71 3.5.2 Reedswood Park 76 3.5 3 Rough Wood 81 3.6 Wolverhampton 3.6.1 Northycote Farm 85 3.6.2 Smestow Valley LNR (Valley Park) 90 3.6.3 West Park 97 4. HABITATS 101 The Endless Village Revisited Technical Background 2005 4.1 Introduction 101 4.2 Heathland 103 4.3 Canals 105 4.4 Rivers and Streams 110 4.5 Waterbodies 115 4.6 Grassland 119 4.7 Woodland 123 5. -

![Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5083/diamond-jubilee-his-highness-the-aga-khan-iv-1957-2017-145083.webp)

Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]

DIAMOND JUBILEE HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN IV [1957 – 2017] . The Diamond Jubilee What is the Diamond Jubilee? The Diamond Jubilee marks the 60th anniversary of His Highness the Aga Khan’s leadership as the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslim Community. On 11th July, 1957, the Aga Khan, at the age of 20, assumed the hereditary office of Imam established by Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family), following the passing of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan. Why is the Community celebrating His Highness the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee? The commemoration of the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee is in keeping with the Ismaili Community’s longstanding tradition of marking historic milestones. Over the past six decades, the Aga Khan has transformed the quality of life of hundreds of millions of people around the world. In the areas of health, education, cultural revitalisation, and economic empowerment, he has inspired excellence and worked to improve living conditions and opportunities in some of the world’s most remote and troubled regions. The Diamond Jubilee is an opportunity for the Shia Ismaili Muslim community, partners of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), and government and faith community leaders in over 25 countries to express their appreciation for His Highness’s leadership and commitment to improve the quality of life of the world’s most vulnerable populations. It is also an occasion for His Highness to recognise the friendship and longstanding support of leaders of governments and partners in the work of the Imamat and to set the direction for the future. -

Queen's Diamond Jubilee 2012

Queen’s Diamond Jubilee 2012 Background word ‘Yobel’, which refers to the ram or ram’s Queen Elizabeth ll has reigned over the United horn with which jubilee years were proclaimed. Kingdom and her Commonwealth countries for In Leviticus it states that such a horn or trumpet 60 years. 2012 and the Diamond Jubilee brings is to be blown on the tenth day of the seventh about many opportunities to celebrate, focus and month after the lapse of ‘seven Sabbaths of years’ give thanks for her Majesty’s faithful, gracious and (49 years) as a proclamation of liberty through - devoted service to the nations. out the land of the tribes of Israel. The year of jubilee was a consecrated year of ‘Sabbath- The Queen reached her 60th anniversary on the rest’ and liberty. During this year all debts were throne on 6 February 2012. On 12 March the cancelled, lands were restored to their original Queen attended Westminster Abbey to celebrate owners and family members were restored to one Commonwealth Day. Main celebrations will take another. place during an extended Bank Holiday weekend from 2 to 5 June. Coronation Day was on 2 June The year of jubilee was also central to the ministry 1953, and there are many stories of how people of of Jesus. In the Gospel of Luke Jesus makes the all ages remember spending that wonderful day. A claim to the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy in few homes had televisions and the BBC broadcast Isaiah 61:1–2. Jesus states that he has come to the Coronation to over 20 million viewers. -

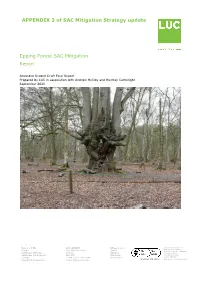

Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report

APPENDIX 2 of SAC Mitigation Strategy update Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report Amended Second Draft Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Andrew McCloy and Huntley Cartwright September 2020 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 250 Waterloo Road Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management SE1 8RD Edinburgh 250 Waterloo Road Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Manchester London SE1 8RD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Project Title: Epping Forest SAC Mitigation. Draft Final Report Client: City of London Corporation Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 April Draft JA JA JA 2019 HL 2 April Draft Final JA JA 2020 HL 3 April Second Draft Final JA, HL, DG/RT, JA 2020 AMcC 4 Sept Amended Second Draft JA, HL, DG/RT, JA JA 2020 Final AMcC Report on SAC mitigation Last saved: 29/09/2020 11:15 Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 This report 2 2 Research and Consultation 4 Documentary Research 4 Internal client interviews 8 Site assessment 10 3 Overall Proposals 21 Introduction 21 Overall principles 21 4 Site specific Proposals 31 Summary of costs 31 Proposals for High Beach 31 Proposals for Chingford Plain 42 Proposals for Leyton Flats 61 Implementation 72 5 Monitoring and Review 74 Monitoring 74 Review 74 Appendix 1 Access survey site notes 75 Appendix 2 Ecological survey site notes 83 Appendix 3 Legislation governing the protection -

February, 1955

Library of The Harvard Musical Association Bulletin No. 23 February, 1955 Library Committee CHARLES R. NUTTER JOHN N. BURK RICHARD G. APPEL CYRUS DURGIN RUDOLPH ELIE Director of the Library and Library and Custodian of the Marsh Room Marsh Room Marsh Room CHARLES R. NUTTER MURIEL FRENCH FLORENCE C. ALLEN To the Members of the Association: Your attention is called to an article in this issue by Albert C. Koch. * * * * REPORT ON THE LIBRARY AND ON THE MARSH ROOM FOR THE YEAR 1954 To the President and the Directors of The Harvard Musical Association: Today, when television and the radio, both A.M. and F.M., are providing much of the intellectual sustenance for the common man and woman, the individual who turns for an intellectual repast to the writers of past centuries and also tries to phrase his thoughts both vocal and written with some regard to the rules of grammar and the principles of rhetoric is regarded as high‐brow and is thrown out of society. I am aware that I lay myself open to the charge of being a high‐brow, a charge that creates no reactionary emotion at all, especially as it comes usually from the low‐brow, and that I may be thrown out of society into a lower stratum, when I state that for the text of this report I have turned to a gentleman whose mortal life spanned the years between 1672 and 1719. Even the low‐brow has probably heard or read the name Joseph Addison, though it may convey nothing to him except the fact that it has an English and not a foreign sound. -

Book2 English

UNITED-KINGDOM JEREMY DAGLEY BOB WARNOCK HELEN READ Managing veteran trees in historic open spaces: the Corporation of London’s perspective 32 The three Corporation of London sites described in ties have been set. There is a need to: this chapter provide a range of situations for • understand historic management practices (see Dagley in press and Read in press) ancient tree management. • identify and re-find the individual trees and monitor their state of health • prolong the life of the trees by management where deemed possible • assess risks that may be associated with ancient trees in particular locations • foster a wider appreciation of these trees and their historic landscape • create a new generation of trees of equivalent wildlife value and interest This chapter reviews the monitoring and manage- ment techniques that have evolved over the last ten years or so. INVENTORY AND SURVEY Tagging. At Ashtead 2237 Quercus robur pollards, including around 900 dead trees, were tagged and photographed between 1994 and 1996. At Burnham 555 pollards have been tagged, most between 1986 Epping Forest. and 1990. At Epping Forest 90 Carpinus betulus, 50 Pollarded beech. Fagus sylvatica and 200 Quercus robur have so far (Photograph: been tagged. Corporation of London). TAGGING SYSTEM (Fretwell & Green 1996) Management of the ancient trees Serially Nails: 7 cm long (steel nails are numbered tags: stainless steel or not used on Burnham Beeches is an old wood-pasture and heath galvanised metal aluminium - trees where a of 218 hectares on acid soils containing hundreds of rectangles 2.5 cm hammered into chainsaw may be large, ancient, open-grown Fagus sylvatica L. -

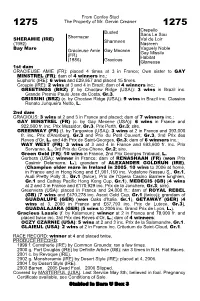

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

Bel Esprit 2021.Qxp Page 9/5/21 2:24 Pm Page 62

Bel Esprit_2021.qxp_Page 9/5/21 2:24 pm Page 62 1 Bel Esprit Bay 1999 16.1 ⁄2 hh Race Record BEL MER (At Talaq; Sir Dapper). 4 wins, $599,575, BELWAZI (Rory's Jester; Scenic). 7 wins, $270,590, SAJC Robert Sangster S.-G1, MRC (WJ Adams S.) VRC Kensington S.-L, MVRC Ladbrokes 55 Second Age Starts Wins 2nds 3rds JRA S.-L, 2d VRC (Ascot Vale S.) Coolmore Stud Challenge H., Sheamus Mills Bloodstock H. 26 5 - - S.-G1, MVRC (AJ Moir S.) Schweppes S.-G2, AUDACIOUS SPIRIT (Zeditave; Snippets). 6 wins, 3133 4 1 Champagne S.-G3. $382,200, BRC Lough Neagh S.-L, 2d ATC Royal KEEN ARRAY (Zabeel; Bluebird). 7 wins, $942,175, Sovereign S.-G2, BRC Dalrello P.-L, 3d BRC Keith 19 8 4 1 VRC (Baguette S.) Gilgai S.-G2, MRC Testa Rossa Noud H.-L, Lightning H.-L. S.-L, Italktravel S.-L, Blue Sapphire S.-L, 2d VRC LADY ESPRIT (Bellotto; Snaadee). 6 wins, Stakes won: $2,073,600 (Ascot Vale S.) Coolmore Stud S.-G1. $352,275, MRC WJ Adams H.-L, 2d VRC Bob SWEET SHERRY (Revoque; Sir Tristram). 4 wins, Hoysted H.-L, MRC Doveton S.-L, 3d MVRC 1st MRC Blue Diamond S.-G1, Caulfield (1200m) $658,300, SAJC (Yallambee Classic) Euclase S.- (MVRC Future Stars Sprint) Carlyon S.-L. BTC Doomben Ten Thousand S.-G1, Doomben (1350m) G2, VRC Maribyrnong Trial S.-L, MVRC William BELTROIS (Noalcoholic; Comeram). 6 wins, VRC Maribyrnong P.-G2, Flemington (1000m) Crockett S.-L, 3d MVRC Atlantic Jewel S.-L. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

New Editions 2012

January – February 2013 Volume 2, Number 5 New Editions 2012: Reviews and Listings of Important Prints and Editions from Around the World • New Section: <100 Faye Hirsch on Nicole Eisenman • Wade Guyton OS at the Whitney • Zarina: Paper Like Skin • Superstorm Sandy • News History. Analysis. Criticism. Reviews. News. Art in Print. In print and online. www.artinprint.org Subscribe to Art in Print. January – February 2013 In This Issue Volume 2, Number 5 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Visibility Associate Publisher New Editions 2012 Index 3 Julie Bernatz Managing Editor Faye Hirsch 4 Annkathrin Murray Nicole Eisenman’s Year of Printing Prodigiously Associate Editor Amelia Ishmael New Editions 2012 Reviews A–Z 10 Design Director <100 42 Skip Langer Design Associate Exhibition Reviews Raymond Hayen Charles Schultz 44 Wade Guyton OS M. Brian Tichenor & Raun Thorp 46 Zarina: Paper Like Skin New Editions Listings 48 News of the Print World 58 Superstorm Sandy 62 Contributors 68 Membership Subscription Form 70 Cover Image: Rirkrit Tiravanija, I Am Busy (2012), 100% cotton towel. Published by WOW (Works on Whatever), New York, NY. Photo: James Ewing, courtesy Art Production Fund. This page: Barbara Takenaga, detail of Day for Night, State I (2012), aquatint, sugar lift, spit bite and white ground with hand coloring by the artist. Printed and published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, NH. Art in Print 3500 N. Lake Shore Drive Suite 10A Chicago, IL 60657-1927 www.artinprint.org [email protected] No part of this periodical may be published without the written consent of the publisher.