Nber Working Paper Series Public Transit Bus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS by MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008

Page 1 of 32 VEHICLE RECALLS BY MANUFACTURER, 2000 Report Prepared 1/16/2008 MANUFACTURER RECALLS VEHICLES ACCUBUIL T, INC 1 8 AM GENERAL CORPORATION 1 980 AMERICAN EAGLE MOTORCYCLE CO 1 14 AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR CO 8 212,212 AMERICAN SUNDIRO MOTORCYCLE 1 2,183 AMERICAN SUZUKI MOTOR CORP. 4 25,023 AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION CORP. 5 1,441 APRILIA USA INC. 2 409 ASTON MARTIN 2 666 ATHEY PRODUCTS CORP. 3 304 B. FOSTER & COMPANY, INC. 1 422 BAYERISCHE MOTOREN WERKE 11 28,738 BLUE BIRD BODY COMPANY 12 62,692 BUELL MOTORCYCLE CO 4 12,230 CABOT COACH BUILDERS, INC. 1 818 CARPENTER INDUSTRIES, INC. 2 6,838 CLASSIC LIMOUSINE 1 492 CLASSIC MANUFACTURING, INC. 1 8 COACHMEN INDUSTRIES, INC. 8 5,271 COACHMEN RV COMPANY 1 576 COLLINS BUS CORPORATION 1 286 COUNTRY COACH INC 6 519 CRANE CARRIER COMPANY 1 138 DABRYAN COACH BUILDERS 1 723 DAIMLERCHRYSLER CORPORATION 30 6,700,752 DAMON CORPORATION 3 824 DAVINCI COACHWORKS, INC 1 144 D'ELEGANT CONVERSIONS, INC. 1 34 DORSEY TRAILERS, INC. 1 210 DUTCHMEN MANUFACTURING, INC 1 105 ELDORADO NATIONAL 1 173 ELECTRIC TRANSIT, INC. 1 54 ELGIN SWEEPER COMPANY 1 40 E-ONE, INC. 1 3 EUROPA INTERNATIONAL, INC. 2 242 EXECUTIVE COACH BUILDERS 1 702 FEATHERLITE LUXURY COACHES 1 83 FEATHERLITE, INC. 2 3,235 FEDERAL COACH, LLC 1 230 FERRARI NORTH AMERICA 8 1,601 FLEETWOOD ENT., INC. 5 12, 119 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 60 7,485,466 FOREST RIVER, INC. 1 115 FORETRAVEL, INC. 3 478 FOURWINNS 2 2,276 FREIGHTLINER CORPORATION 27 233,032 FREIGHTLINER LLC 1 803 GENERAL MOTORS CORP. -

Hvy Dty Veh & Eng Res. Guide

The U.S. Department Of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency And Renewable Energy’s National Alternative Fuels Hotline Heavy-Duty Vehicle and Engine Resource Guide This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CONTACT THE HOTLINE 800-423-1DOE • 703-528-3500 FAX: 703-528-1953 EMAIL: [email protected] Introduction Engine manufacturers are moving forward when it comes to alternative fuel engine technology. This model year (MY96), heavy-duty engine manufacturers are offering a number of natural gas models with additional models nearing production. Electric vehicle manufacturers have several products available with new models nearing completion. Although Caterpillar is the only manufacturer offering propane as a fuel option, Detroit Diesel Corp. (DDC) will be demonstrating a prototype model in 1996, and Cummins will release a model within MY96. Many manufacturers are offering natural gas engines in response to California Air Resource Board’s strict bus emission standards which are effective MY96. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

CNG As a Transit Bus Fuel

TheThe TransitTransit BusBus NicheNiche MarketMarket ForFor AlternativeAlternative Fuels:Fuels: ModuleModule 3:3: OverviewOverview ofof CompressedCompressed NaturalNatural GasGas asas aa TransitTransit BusBus FuelFuel CleanClean CitiesCities CoordinatorCoordinator ToolkitToolkit PreparedPrepared byby TIAXTIAX LLC,LLC, IrvineIrvine OfficeOffice DecemberDecember 20032003 TIAX LLC One Park Plaza, 6th Floor Irvine, California 92614 949-833-7131 / [email protected] Options for Natural Gas Fueling in Transit • Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) – Pipeline natural gas: methane with other hydrocarbons – Pressurized to 3,600 psi – Fueling accomplished by pressure transfer to vehicle – About 12% of transit buses in the U.S. now use conventional CNG – Largest users include LACMTA, MARTA, NY DOT, Pierce Transit, Washington D.C. (WMATA), Cleveland, Sacramento • Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) – Nearly pure methane (~98%) liquefied at very low temperatures – Liquid transfer to vehicle – Largest users are Phoenix, Orange County (CA), Dallas, and Tempe – Newer users include Santa Monica, Long Beach • LNG to CNG (“LCNG”) – Vaporized LNG (also nearly pure methane) – Liquid to gas conversion, then pressure transfer to vehicle – Sun Metro, OmniTrans, others use this approach Document Code 1 Methane Content in Pipeline Natural Gas Varies Regionally Methane Molecule Typical Composition of Pipeline Natural Gas What are the Implications of the Resulting CNG Fuel Quality Variations? • CNG with lower methane content (higher levels of ethane, propane, or butane) has resulted in some adverse affects on heavy-duty NG engine performance (e.g., misfire, stumble and underrated operation, engine knock, overheating) • However, today’s lean-burn closed-loop NG engines for transit (e.g., C Gas Plus and DDC S50G) are better able to tolerate and compensate for variations • Compromises in emissions performance have been found to be modest Document Code 2 Numerous OEMs Offer Natural Gas Transit Buses and Paratransit Vehicles Natural Gas Bus Manufacturer Models Available Champion Bus, Inc. -

To View All Safety Act Settlements from 1996-2009

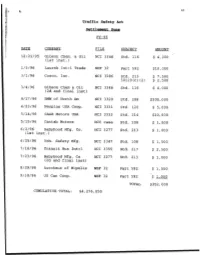

2 41 Traffic Safety Act Settlement Sums FY-96 -DATE COMPANY FILE SUBJECT AMOUNT 12/21/95 Gibson Chem. & Oil NCI 3346 Std. 116 $ 4,000 (1st inst.) 1/3/96 Laurek Int=l Trade NEF 32 Part 592 $10,000 3/1/96 Cosco, Inc. NCI 3286 Std. 213 $ 7,500 30119 (c)(2) $ 2,500 3/4/96 Gibson Chem & Oil NCI 3346 Std. 116 $ 4,000 (2d and final inst) 4/17/96 BMW of North Am NCI 3320 Std. 208 $300,000 4/23/96 Neoplan USA Cow. NCI 3331 Std. 120 $ 5,000 5/14/ 96 SAAB Motors USA NCI 3333 Std. 214 $10,000 5/15/96 Cantab Motors NCC case Std. 208 $ 1,000 6/2/96 Babyhood Mfg. Co. NCI 3277 Std. 213 $ 1,000 (1st inst.) 6/25/96 Veh. Safety Mfg. NCI 3347 Std. 108 $ 1,500 7/16/96 Transit Bus Int=l NCI 3355 Std. 217 $ 2,500 7/23/96 Babyhood Mfg. Co NCI 3277 Std. 213 $ 1.000 (2d and final inst) 8/29/96 Autohaus of M=polis NEF 32 Part 592 $ 1,000 9/30/96 US Car Corp. NEF 32 Part 592 $ 1,000 TOTAL $352,000 CUMULATIVE TOTAL: $4,276,050 42 I Traffic Safety Act Settlement Sums FY-97 -DATE COMPANY FILE SUBJECT AMOUNT 10/96 American Honda EA9 4 - 03 5 30118(c) (1) $ 50,000 Motor Co. 30120 12/11/96 Motorsport Imports Sec. 591.8(e) 159,126 1/2/97 Cosco, Inc. NCI 3358 Std. 213 5,000 1/15/97 Takata Motor EA94-03 6 30118(c) (1) cow. -

Motorcoach Run-Off-The-Road Accident Tallulah, Louisiana October 13, 2003

National Transportation Safety Board Washington, D.C. 20594 PRSRT STD OFFICIAL BUSINESS Postage & Fees Paid Penalty for Private Use, $300 NTSB Permit No. G-200 Motorcoach Run-Off-The-Road Accident Tallulah, Louisiana October 13, 2003 Highway Accident Report NTSB/HAR-05/01 PB2005-916201 Notation 7711 National National Transportation Transportation Safety Board Safety Board Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C. Highway Accident Report Motorcoach Run-Off-The-Road Accident Tallulah, Louisiana October 13, 2003 NTSB/HAR-05/01 PB2005-916201 National Transportation Safety Board Notation 7711 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Adopted April 19, 2005 Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2005. Motorcoach Run-Off-The-Road Accident, Tallulah, Louisiana, October 13, 2003. Highway Accident Report NTSB/HAR-05/01. Washington, DC. Abstract: At 10:50 a.m. on October 13, 2003, a 1992 Neoplan USA Corporation 49-passenger motorcoach, owned and operated by the First Baptist Church of Eldorado, Texas, was traveling eastbound on Interstate 20 near Tallulah, Louisiana. The motorcoach, carrying 14 passengers, was en route from Shreveport, Louisiana, to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, as part of a multicity sightseeing tour that had originated in Eldorado. As the motorcoach approached milepost 168, it drifted rightward from the travel lanes and onto the shoulder, where it struck the rear of a 1988 Peterbilt tractor semitrailer operated by Alpha Trucking, Inc., which was stopped on the shoulder at milepost 167.9. As both vehicles moved forward, the motorcoach rotated clockwise slightly and the semitrailer rotated counter-clockwise slightly; the vehicles remained together. They traveled approximately 62 feet and came to rest, still oriented to the east, adjacent to the right side of the interstate on the outside shoulder. -

Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making

Project No: FTA-VA-26-7222-2004.1 Federal United States Transit Department of August 2004 Administration Transportation CharacteristicsCharacteristics ofof BusBus RapidRapid TransitTransit forfor Decision-MakingDecision-Making Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES August 2004 COVERED BRT Demonstration Initiative Reference Document 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making 6. AUTHOR(S) Roderick B. Diaz (editor), Mark Chang, Georges Darido, Mark Chang, Eugene Kim, Donald Schneck, Booz Allen Hamilton Matthew Hardy, James Bunch, Mitretek Systems Michael Baltes, Dennis Hinebaugh, National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Lawrence Wnuk, Fred Silver, Weststart - CALSTART Sam Zimmerman, DMJM + Harris 8. -

Technology of Articulated Transit Buses Transportation 6

-MA-06-01 20-82-4 DEPARTMENT of transportation HE SC-UMTA-82-17 1 8. b .\37 JUL 1983 no. DOT- LIBRARY TSC- J :aT \- 8 ?- Technology of U.S. Department of Transportation Articulated Transit Buses Urban Mass Transportation Administration Office of Technical Assistance Prepared by: Office of Bus and Paratransit Systems Transportation Systems Center Washington DC 20590 Urban Systems Division October 1982 Final Report NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Govern- ment assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse prod- 1 ucts or manufacturers . Trade or manufacturers nam&s appear herein solely because they are con- sidered essential to the object of this report. 4 v 3 A2>7 ?? 7 - c c AST* Technical Report Page V ST‘ (* Documentation 1 . Report No. 2. Government A ccession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UMTA-MA-06-0 120-82- 4. Title and Subti tie ~6. Report Date October 1982 DEPARTMENT OF I TECHNOLOGY OF ARTICULATED TRANSIT BUSES TRANSPORTATION 6. Performing Organization Code TSC/DTS-6 j JUL 1983 8 . Performing Organization Report No. 7. Author's) DOT-TSC-UMTA-82-17 Richard G. Gundersen | t |kh a R 9. Performing Organization Name and Address jjo. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) U.S. Department of Transportation UM262/R2653 Research and Special Programs Administration 11. Contract or Grant No. Transportation Systems Center Cambridge MA 02142 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address U.S. -

The Us Transit Bus Manufacturing Industry

MTI Funded by U.S. Department of Services Transit Census California of Water 2012 Transportation and California The US Transit Bus Department of Transportation Manufacturing Industry MTI ReportMTI 12-02 December 2012 MTI Report 12-66 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER LEAD UNIVERSITY OF MNTRC Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation MTI/MNTRC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Founder, Honorable Norman Joseph Boardman (Ex-Officio) Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2019) Richard A. White (Ex-Officio) Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to Mineta (Ex-Officio) Chief Executive Officer Principal and Chair of Board Interim President and CEO be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Secretary (ret.), US Department of Amtrak Lea+Elliot, Inc. American Public Transportation Transportation Association (APTA) Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Vice Chair Anne Canby (TE 2017) Will Kempton (TE 2019) Centers Program, the California Department of -

Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making

Project No: FTA-VA-26-7222-2004.1 Federal United States Transit Department of August 2004 Administration Transportation CharacteristicsCharacteristics ofof BusBus RapidRapid TransitTransit forfor Decision-MakingDecision-Making Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES August 2004 COVERED BRT Demonstration Initiative Reference Document 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making 6. AUTHOR(S) Roderick B. Diaz (editor), Mark Chang, Georges Darido, Mark Chang, Eugene Kim, Donald Schneck, Booz Allen Hamilton Matthew Hardy, James Bunch, Mitretek Systems Michael Baltes, Dennis Hinebaugh, National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Lawrence Wnuk, Fred Silver, Weststart - CALSTART Sam Zimmerman, DMJM + Harris 7. -

Bus and Coach WMI - World Manufacturer Identifier the First Three Characters of the VIN Number Uniquely Identifies the Manufacturer of the Vehicle

WMI tvornice autobusa svijeta http://eurobus.hr Page 1 of 15 Bus and Coach WMI - world manufacturer identifier The first three characters of the VIN number uniquely identifies the manufacturer of the vehicle. World Manufacturer Identifier or WMI code. Some vehicle manufacturers use the third character as a code for a vehicle category (e.g., bus or truck), a division within a manufacturer, or both. For example, within 1G (assigned to General Motors in the United States), 1G1 represents Chevrolet passenger cars; 1G2, Pontiac passenger cars; and 1GC, Chevrolet trucks. Here is an up to date list of world bus manufacturers. WMI VIN Example Company Marque Country AA9 - BUSAF Bauer - South AU1 - South African Minibus & Vehicles - Africa AA9 - Centurion Bus Manufacturers - MD1 - MAN Truck & Bus (SA) (PTY) - AA9 - BUSAF Cape - RW1 - BUSAF Port Elizabeth - AAM AC9 AZ1 AC9 CC1 DG2 - Carroserie Industrielle du Maroc - Morocco JAA JAAN1R70TW7100159 Isuzu Japan JAJ - Izuzu - JAL JALLT112LM3000091 Isuzu - JA5 - Mitsubishi - JB5 - Mitsubishi - JHC - Hino Motors - JJ5 - Mitsubishi - JMA JMAG2P02VKA000929 Mitsubishi - JP5 - Mitsubishi - JSA JSAEDA21V00125255 Suzuki - JT1 JT1WLHG1W00023196 Toyota - JT7 JT743PB5108001837 Toyota - - South KLD - Asia Motors - Korea KLH - Asia Motors - KM2 - Hyundai Motor Company - KM5 - Hyundai Motor Company - KM6 - Hyundai Motor Company - KM7 - Hyundai Motor Company - KM8 - Hyundai Motor Company - KMA - Asia Motors - KMC - Hyundai Motor Company - KMD - Dong-A Motor Company - KMH - Hyundai Motor Company - KMJ KMJPL19YPPU003885 -

New Mexico UCR Form

CRASH STATE OF NEW MEXICO INVESTIGATION UNIFORM CRASH REPORT SH 10074 Rev July 2018 NMDOTUCR REPORTING DEPARTMENT Hit-and-Run E July 2018 On Pvt Property FATAL PROPERTY UNDER $500 Case Number: DAMAGE School Bus Directly Involved Secondary Crash School Bus Indirectly Involved INJURY ONLY $500 OR MORE Commercial Vehicle Involved Agency Code: CAD Num: CRASH DATE (MM/DD/YYYY) MILITARY TIME CITY OCCURRED IN COUNTY Sun M Tu W Th F Sat OCCURRED ON: (Route No. or Name, Address) AT INTERSECTION WITH: OTHER FEET N NE NW S SE SW E W MILEPOST - PERMANENT LANDMARK - COUNTY LINE – INTERSECTION LAT: LOCATION MILES LONG: Work Zone-Construction TRIBAL LAND? FIRST Collision w/Motor Vehicle Collision w/Animal ANALYSIS On Roadway Collision w/Person CRASH Work Zone-Maintenance HARMFUL Collision w/Fixed Object CODE: Off Roadway Non-Collision OCCURRED Yes No EVENT Non-Trafficway Work Zone-Utility Collision w/Other Non-Fixed Object LOCATION (FHE) Other (Specify in Narrative) OF FHE: VEHICLE NO. MV Unit Type N NE NW S SE SW E W On: Left Scene of Crash Posted Speed Safe Speed HEADED 1 Yes No Driver’s Full Name (Last, First, Middle) Address Driver’s License Number State Type CDL Status Restrictions Endorsements Expires Interlock City/State ZIP Code Phone Date of Birth - MM/DD/YYYY Occupation Incident Responder Sex Injury OP OP Used Airbag Seat Pos. Race Ejected Med Trans Age (M/F) Code Code Properly Deploy EMS # Seat Pos. Occupant’s Name (Last, First, Middle) Occupant’s Address (City, State, ZIP) Vehicle Yr. Vehicle Make Model Color Body Style Cargo Body Type Vehicle Use (1) Vehicle Use (2) Vehicle Use (3) Towed? Damage Severity Extent 1 2 3 4 5 Number of Occupants: ________ Yes No Heavy Disabled License Yr.