Horatio Nelson: Emblem of Empire in an Age of Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Channel Islands Great War Study Group

CHANNEL ISLANDS GREAT WAR STUDY GROUP Le Défilé de la Victoire – 14 Juillet 1919 JOURNAL 27 AUGUST 2009 Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All It will not have escaped the notice of many of us that the month of July, 2009, with the deaths of three old gentlemen, saw human bonds being broken with the Great War. This is not a place for obituaries, collectively the UK’s national press has done that task more adequately (and internationally, I suspect likewise for New Zealand, the USA and the other protagonists of that War), but it is in a way sad that they have died. Harry Patch and Henry Allingham could recount events from the battles at Jutland and Passchendaele, and their recollections have, in recent years, served to educate youngsters about the horrors of war, and yet? With age, memory can play tricks, and the facts of the past can be modified to suit the beliefs of the present. For example, Harry Patch is noted as having become a pacifist, and to exemplify that, he stated that he had wounded, rather than killed, a German who was charging Harry’s machine gun crew with rifle and bayonet, by Harry firing his Colt revolver. I wonder? My personal experience in the latter years of my military career, having a Browning pistol as my issued weapon, was that the only way I could have accurately hit a barn door was by throwing the pistol at it! Given the mud and the filth, the clamour and the noise, the fear, a well aimed shot designed solely to ‘wing’ an enemy does seem remarkable. -

Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report 2009 (April 2009 - March 2010)

Department for Culture, Media and Sport Architecture and Historic Environment Division Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report 2009 (April 2009 - March 2010) Compiled by English Heritage for the Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites. Text was also contributed by Cadw, Historic Scotland and the Environment and Heritage Service, Northern Ireland. s e vi a D n i t r a M © Contents ZONE ONE – Wreck Site Maps and Introduction UK Designated Shipwrecks Map ......................................................................................3 Scheduled and Listed Wreck Sites Map ..........................................................................4 Military Sites Map .................................................................................................................5 Foreword: Tom Hassall, ACHWS Chair ..........................................................................6 ZONE TWO – Case Studies on Protected Wreck Sites The Swash Channel, by Dave Parham and Paola Palma .....................................................................................8 Archiving the Historic Shipwreck Site of HMS Invincible, by Brandon Mason ............................................................................................................ 10 Recovery and Research of the Northumberland’s Chain Pump, by Daniel Pascoe ............................................................................................................... 14 Colossus Stores Ship? No! A Warship Being Lost? by Todd Stevens ................................................................................................................ -

Commemorating Trafalgar Day 2020

COMMEMORATING TRAFALGAR DAY 2020 Wednesday 21 October As we know, our National EVENING SCHEDULE Trafalgar Day this year is to be 5.50pm Unwind from school and get in the mood for Trafalgar Day by scaled down due to the ongoing learning about the day through our fact finder. pandemic. But don’t worry! We’ve put together this activity 6.00pm Create a drink for the evening. Smoothy or squash, what’s pack for you to complete on going to be your tonic to keep scurvy at bay? the evening of Wednesday 6.30pm We’ll be launching the official Trafalgar Day video on our 21 October. social media channels. Watch to see cadets lay the memorial Work through the activities with wreath on Trafalgar Square and share a moment’s silence to friends or on your own and be remember those who have fallen. sure to join us on social media 6.45pm Post your virtual salutes to your social media channels and on the evening by using the be sure to tag @SeaCadetsUK in and we’ll share them on #VirtualTrafalgarDay2020 Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tik-Tok. 7.00pm Tackle our two activities. Create your bicorn hat and craft your floating craft using the guidelines in the pack. 2 6 FACT FINDING VOYAGE HMS Victory had 104 guns and was constructed from 6,000 oaks and elm trees. Its sails required 26 miles of rope 1 and rigging for the three masts, and On 21 October 1805, the British fleet, because there were so many manual jobs, under the command of Admiral Nelson, it was crewed by over 800 men. -

Newslettejan2006

NEWSLETTER of THE NELSON SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA INC January 2006 Souvenir Edition THE BI-Centennial CELEBRATIONS Vice Admiral Viscount Lord Nelson 2006 PROGRAMME St Michael’s Church Hall, Cnr. the Promenade & Gunbower Rd, Mt Pleasant, WA Meetings at 7pm for 7.30 start. Feb 13th — 7pm Time Capsule finally put to rest in Memorial Garden of St Michael’s followed at 7.30pm by a lecture by Mike Sargeant Nelson’s Funeral Mar 20th — AGM - Short talk on ‘Baudin’ by a member of the Baudin Society. May 8th — To be announced later July 10th — Video — 2005 Fleet review Sept 11th — Nelson’s Trial — to be confirmed Oct 22nd — Memorial Service Nov 10th — Pickle Night. Highlights of the Royal Naval Association. Bi-Centennial Trafalgar Dinner at the South of Perth Yacht Club, 21 October 2005 South of Perth Yacht Club Foreshore Pictures of Evening Colours and the RAN band Page 3 Newsletter of the Nelson Society of Australia Inc. Jan. 2006 More Highlights HMS Voctory Page 4 Newsletter of the Nelson Society of Australia Inc. Jan. 2006 The Trafalgar Dinner 21 October 2005 Ivan Hunter & Rear Admiral Phil Kennedy Commodore David Orr Nelson’s Writing set This bone china writing set was in the possession of Vice Admiral Lord Nelson on the Victory at the Battle of Trafalgar. Its present owners are the Family descendants of Nelson’s sister, Kitty Matcham. Below left is Mrs Audrey Oliver, a direct descendant of Nelson’s Sister. Below is Mark Kumara also a Nelson family descendant. Page 5 Newsletter of the Nelson Society of Australia Inc. -

Lyings in State

Lyings in state Standard Note: SN/PC/1735 Last updated: 12 April 2002 Author: Chris Pond Parliament and Constitution Centre On Friday 5 April 2002, the coffin of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother was carried in a ceremonial procession to Westminster Hall, where it lay in state from the Friday afternoon until 6 a.m. on Tuesday 9 April. This Standard Note gives a history of lying in state from antiquity, and looks at occasions where people have lain in state in the last 200 years. Contents A. History of lying in state 2 B. Lyings in state in Westminster Hall 2 1. Gladstone 3 2. King Edward VII 3 3. Queen Alexandra 5 4. Victims of the R101 Airship Disaster, 1930 5 5. King George V 6 6. King George VI 6 7. Queen Mary 6 8. Sir Winston Churchill 7 9. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother 7 C. The pattern 8 Annex 1: Lyings in state in Westminster Hall – Summary 9 Standard Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise others. A. History of lying in state The concept of lying in state has been known from antiquity. In England in historical times, dead bodies of people of all classes “lay” – that is, were prepared and dressed (or “laid out”) and, placed in the open coffin, would lie in a downstairs room of the family house for two or three days whilst the burial was arranged.1 Friends and relations of the deceased could then visit to pay their respects. -

Portsmouth Dockyard in the Twentieth Century1

PART THREE PORTSMOUTH DOCKYARD IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY1 3.1 INTRODUCTION The twentieth century topography of Portsmouth Dockyard can be related first to the geology and geography of Portsea Island and secondly to the technological development of warships and their need for appropriately sized and furnished docks and basins. In 2013, Portsmouth Naval Base covered 300 acres of land, with 62 acres of basin, 17 dry docks and locks, 900 buildings and 3 miles of waterfront (Bannister, 10 June 2013a). The Portsmouth Naval Base Property Trust (Heritage Area) footprint is 11.25 acres (4.56 hectares) which equates to 4.23% of the land area of the Naval Base or 3.5% of the total Naval Base footprint including the Basins (Duncan, 2013). From 8 or 9 acres in 1520–40 (Oppenheim, 1988, pp. 88-9), the dockyard was increased to 10 acres in 1658, to 95 acres in 1790, and gained 20 acres in 1843 for the steam basin and 180 acres by 1865 for the 1867 extension (Colson, 1881, p. 118). Surveyor Sir Baldwin Wake Walker warned the Admiralty in 1855 and again in 1858 that the harbour mouth needed dredging, as those [ships] of the largest Class could not in the present state of its Channel go out of Harbour, even in the event of a Blockade, in a condition to meet the Enemy, inasmuch as the insufficiency of Water renders it impossible for them to go out of Harbour with all their Guns, Coals, Ammunition and Stores on board. He noted further in 1858 that the harbour itself “is so blocked up by mud that there is barely sufficient space to moor the comparatively small Force at present there,” urging annual dredging to allow the larger current ships to moor there. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Channel Island Headstones for the Website

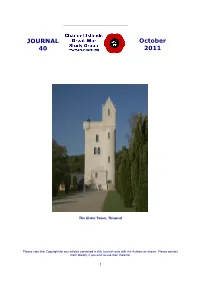

JOURNAL October 40 2011 The Ulster Tower, Thiepval Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All I do not suppose that the global metal market features greatly in Great War journals and magazines, but we know, sometimes to our cost, that the demand from the emerging economies such as Brazil, China and India are forcing prices up, and not only for newly manufactured metals, but also reclaimed metal. There is a downside in that the higher prices are now encouraging some in the criminal fraternity to steal material from a number of sources. To me the most dangerous act of all is to remove railway trackside cabling, surely a fatal accident waiting to happen, while the cost of repair can only be passed onto the hard-pressed passenger in ticket price rises, to go along with the delays experienced. Similarly, the removal of lead from the roofs of buildings can only result in internal damage, the costs, as in the case of the Morecambe Winter Gardens recently, running into many thousands of pounds. Sadly, war memorials have not been totally immune from this form of criminality and, there are not only the costs associated as in the case of lead stolen from church roofs. These thefts frequently cause anguish to the relatives of those who are commemorated on the vanished plaques. But, these war memorial thefts pale into insignificance by comparison with the appalling recent news that Danish and Dutch marine salvage companies have been bringing up components from British submarine and ships sunk during the Great War, with a total loss of some 1,500 officers and men. -

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar

Lord Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar Lord Nelson and the early years Horatio Nelson was born in Norfolk in 1758. As a young child he wasn’t particularly healthy but he still went on to become one of Britain’s greatest heroes. Nelson’s father, Edmund Nelson, was the Rector of Burnham Thorpe, the small Norfolk village in which they lived. His mother died when he was only 9 years old. Nelson came from a very big family – huge in fact! He was the sixth of 11 children. He showed an early love for the sea, joining the navy at the age of just 12 on a ship captained by his uncle. Nelson must have been good at his job because he became a captain at the age of 20. He was one of the youngest-ever captains in the Royal Navy. Nelson married Frances Nisbet in 1787 on the Caribbean island of Nevis. Although Nelson was married to Frances, he fell in love with Lady Hamilton in Naples in Italy. They had a child together, Horatia in 1801. Lord Nelson, the Sailor Britain was at war during much of Nelson’s life so he spent many years in battle and during that time he became ill (he contracted malaria), was seriously injured. As well as losing the sight in his right eye he lost one arm and nearly lost the other – and finally, during his most famous battle, he lost his life. Nelson’s job helped him see the world. He travelled to the Caribbean, Denmark and Egypt to fight battles and also sailed close to the North Pole. -

The U.S. Capitol Visitor Center—Ten Years of Serving Congress and the American People

THE U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER—TEN YEARS OF SERVING CONGRESS AND THE AMERICAN PEOPLE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 16, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on House Administration ( Available on the Internet: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 32–666 WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 02:24 Nov 14, 2018 Jkt 032666 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\A666.XXX A666 COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION GREGG HARPER, Mississippi, Chairman RODNEY DAVIS, Illinois, Vice Chairman ROBERT A. BRADY, Pennsylvania, BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia Ranking Member MARK WALKER, North Carolina ZOE LOFGREN, California ADRIAN SMITH, Nebraska JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland BARRY LOUDERMILK, Georgia (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 02:24 Nov 14, 2018 Jkt 032666 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 E:\HR\OC\A666.XXX A666 THE U.S. CAPITOL VISITOR CENTER—TEN YEARS OF SERVING CONGRESS AND THE AMERICAN PEOPLE WEDNESDAY, MAY 16, 2018 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, COMMITTEE ON HOUSE ADMINISTRATION, Washington, DC. The Committee met, pursuant to call, at 11:00 a.m., in Room 1310, Longworth House Office Building, Hon. Gregg Harper [Chair- man of the Committee] presiding. Present: Representatives Harper, Davis, Walker, Brady, and Raskin. Staff Present: Sean Moran, Staff Director; Kim Betz, Deputy Staff Director/Policy and Oversight; Dan Jarrell, Legislative Clerk; Matt Field, Director of Oversight; Ed Puccerella, Professional Staff; Erin McCracken, Communications Director; Khalil Abboud, Minor- ity Deputy Staff Director; Kristie Muchnok, Minority Professional Staff. The CHAIRMAN. I now call to order the Committee on House Ad- ministration for purpose of today’s hearing, examining the United States Capitol Visitor Center as it approaches its tenth anniver- sary. -

The Battle of Britain, 1945–1965 : the Air Ministry and the Few / Garry Campion

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–28454–8 © Garry Campion 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–28454–8 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

LINDSEY HUGHES the Funerals of the Russian Emperors and Empresses

LINDSEY HUGHES The Funerals of the Russian Emperors and Empresses in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 395–419 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 14 The Funerals of the Russian Emperors and Empresses LINDSEY HUGHES In the eighteenth century eight Russian monarchs and ex- monarchs 'departed this temporal existence for eternal bliss'. 1 (See Table 14.1.) Six were laid to rest in the Cathedral of SS Peter and Paul in St Petersburg, one of them, Peter III (1761-2), thirty-four years after his first burial. Peter II (1727-30) was buried in Moscow in 1730, while Ivan VI (1740---1), deposed as an infant in 1741, did not merit a state funeral by the time he was killed in 1764. As is well known, the eighteenth century occupied a rather different place in the scheme of Russian history and culture than it did for most countries further west, where essen- tially there was continuity between the seventeenth and eight- eenth centuries.