Rebecca Lynne Clark Mane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

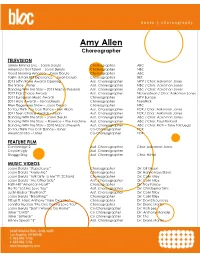

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 Nominees Are in

The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 Nominees Are In ... Kanye West Leads The Pack With Nine Nominations As Hip-Hop's Crowning Night Returns to Atlanta on Saturday, October 10 and Premieres on BET Tuesday, October 27 at 8:00 p.m.* NEW YORK, Sept.16 -- The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 nominations were announced earlier this evening on 106 & PARK, along with the highly respected renowned rapper, actor, screenwriter, film producer and director Ice Cube who will receive this year's "I AM HIP-HOP" Icon Award. Hosted by actor and comedian Mike Epps, the hip-hop event of the year returns to Atlanta's Boisfeuillet Jones Civic Center on Saturday, October 10 to celebrate the biggest names in the game - both on the mic and in the community. The BET HIP-HOP AWARDS '09 will premiere Tuesday, October 27 at 8:00 PM*. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20070716/BETNETWORKSLOGO ) The Hip-Hop Awards Voting Academy which is comprised of journalists, industry executives, and fans has nominated rapper, producer and style aficionado Kanye West for an impressive nine awards. Jay Z and Lil Wayne follow closely behind with seven nominations, and T.I. rounds things off with six nominations. Additionally, BET has added two new nomination categories to this year's show -- "Made-You-Look Award" (Best Hip Hop Style) which will go to the ultimate trendsetter and "Best Hip-Hop Blog Site," which will go to the online site that consistently keeps hip-hop fans in the know non-stop. ABOUT ICE CUBE Veteran rapper, Ice Cube pioneered the West Coast rap movement back in the late 80's. -

Lasvegasiii Overall Score Reports

LasVegasIII Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance 1 1556 The Ground - Dancers World Production - Hacienda Hts, CA 84.4 Stacy Sun 2 1431 Skyscraper - Studio X Dance Complex - Rancho Cucamonga, CA 84.3 Bella Mendez 3 1548 Legacy Of Hope - Dancers World Production - Hacienda Hts, CA 84.2 Chloe Li 4 1739 Let Her Go - Corona Dance Academy - Corona, CA 84.1 Stella Jones 5 195 Wonderful World - Boutique Dance Academy - Castle Rock, CO 84.0 Violet Mouttet 5 1953 If they could see me now - Warehouse Dance Studio - Phoenix, AZ 84.0 Kate Levine 6 1712 Burn It Up - Supreme Dance Center - Murrieta, CA 83.7 Natalie Jaimes 7 189 Bridge Of Light - Boutique Dance Academy - Castle Rock, CO 83.6 Elliott Henderson 8 71 Hallelujah - Boutique Dance Academy - Castle Rock, CO 83.5 Skyla Edgar 8 1435 BEAT - Studio X Dance Complex - Rancho Cucamonga, CA 83.5 Emma Gerberding 8 1451 No Excuses - Studio X Dance Complex - Rancho Cucamonga, CA 83.5 Sophia Igne 8 1542 Great Love of all - Dancers World Production - Hacienda Hts, CA 83.5 Stephanie Sun 8 1969 Umbrella Dance - Li's Ballet Studio - Temple City, CA 83.5 Angela Yang 9 1888 Variation from Paquita - Elite Ballet Theatre - Temple City, CA 83.2 Michelle Zhang 10 1429 Respect - Studio X Dance Complex - Rancho Cucamonga, CA 83.0 Alayah Carter Advanced 1 1923 Fields of Gold - Orange County Performing Arts - Anaheim Hills, CA 111.7 Audrina Mossembekker 2 1436 Heart Cry - Studio X Dance Complex - Rancho Cucamonga, CA 111.6 Nicholas Turner 3 192 Shelter - Boutique Dance Academy - Castle Rock, -

Process and Product--A Reassessment of Students

R E P O R T RESUMES ED 015 687 EM 006 228 PROCESS AND PRODUCT - -A REASSESSMENT OF STUDENTS AND PROGRAM. THE CREATIVE INTELLECTUAL STYLE IN GIFTED ADOLESCENTS, REPORT III. FINAL REPORT. BY- CREWS, ELIZABETH MONROE MICHIGAN ST. UNIV., EAST LANSING REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VIIA-647-FT-3-PHASE-II PUB DATE 66 GRANT OEG-7-32-0410-222 EDRS PRICE MF -$1.25 HC-$12.86 320F. DESCRIPTORS- *GIFTED, CREATIVE THINKING, ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE, PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS, ADOLESCENTS THIS FINAL REPORT OF A SERIES ELABORATES DAiA FROM REPORT IIN SIX INTENSIVE CASE STUDIES OF THREE TYPES OF GIFTED ADOLESCENTS (CREATIVE INTELLECTUAL, STUDIOUS, SOCIAL LEADER) IDENTIFIED BY SELF-REPORT, AND TESTS THE STRENGTH AND DURABILITY OF ATTITUDE CHANGES RESULTING FROM CURRICULUM EXPERIMENTS DESCRIBED IN REPORT II. RESEARCH RELEVANT TO THE CREATIVE INTELLECTUAL STYLE IN BOTH ADULTS AND ADOLESCENTS IS CITED. ASSUMFTIOMS THROUGHOUT THIS RESEARCH ARE THAT EDUCATIONAL AIMS FOR GIFTED ADOLESCENTS SHOULD INCLUDE DEVELOPMENT OF IDENTITY, MOTIVATION TO LEARN, AND OPENNESS TO CHANGE. FORMAL AND INFORMAL MEASURES ON TESTS ADMINISTERED ONE YEAR AFTER THEY WERE GIVEN FOR REPORT II EXPERIMENTS SHOWED CONTINUING TRENDS OF ATTITUDE CHANGES TOWARD CREATIVE INTELLECTUALITY FOR ALL POPULATION SUB-GROUPS, BOTH EXPERIMENTAL AND CONTROL, BUT NO APPARENT INCREASE IN PROBLEM- SOLVING SKILLS. THESE RESULTS ARE FURTHER DISCUSSED IN THE CONTEXT OF )HE CASE STUDIES, AND IN TERMS OF CONCURRENT SOCIAL Tr''.ENDS.(LH) fr THE C.' EA TI IN UAL STYLE GIFT D 4 ESCENTS Ykizrvory-e.,avuov (.1principal investigator 's I. motivation tolearn ESS AND PRODUCT areassessmentof$tudents andprogram A. *./ THE CREATIVE INTELLECTUAL STYLE IN GIFTED ADOLESCENTS Process and Product: A Reassessment of Students and Program Elizabeth Monroe Drews Professor of Education Portland State College Portland, Oregon Final Report of Title VII, Project No. -

Willieverbefreelikeabird Ba Final Draft

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Japanskt mál og menning Fashion Subcultures in Japan A multilayered history of street fashion in Japan Ritgerð til BA-prófs í japönsku máli og menningu Inga Guðlaug Valdimarsdóttir Kt: 0809883039 Leðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorkellsdóttir September 2015 1 Abstract This thesis discusses the history of the street fashion styles and its accompanying cultures that are to be found on the streets of Japan, focusing on the two most well- known places in Tokyo, namely Harajuku and Shibuya, as well as examining if the economic turmoil in Japan in the 1990s had any effect on the Japanese street fashion. The thesis also discusses youth cultures, not only those in Japan, but also in North- America, Europe, and elsewhere in the world; as well as discussing the theories that exist on the relation of fashion and economy of the Western world, namely in North- America and Europe. The purpose of this thesis is to discuss the possible causes of why and how the Japanese street fashion scene came to be into what it is known for today: colorful, demiurgic, and most of all, seemingly outlandish to the viewer; whilst using Japanese society and culture as a reference. Moreover, the history of certain street fashion styles of Tokyo is to be examined in this thesis. The first chapter examines and discusses youth and subcultures in the world, mentioning few examples of the various subcultures that existed, as well as introducing the Japanese school uniforms and the culture behind them. The second chapter addresses how both fashion and economy influence each other, and how the fashion in Japan was before its economic crisis in 1991. -

![[Countable], Pl.-Gees. a Person Who Has Been Forced to Leave Their Country in Order to Escape War, Persecution, Or Natural Disaster](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4597/countable-pl-gees-a-person-who-has-been-forced-to-leave-their-country-in-order-to-escape-war-persecution-or-natural-disaster-374597.webp)

[Countable], Pl.-Gees. a Person Who Has Been Forced to Leave Their Country in Order to Escape War, Persecution, Or Natural Disaster

MORE THAN WORDS Refugee /rɛfjʊˈdʒiː/ n. [countable], pl.-gees. A person who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster. unicef.es/educa MORE THAN WORDS Where does the word refugee come from? From Ancient Greek: φυγή From Latin: fugere (flight) [phyge], flight, escape In Latin mythology, Phyge is known In Greek mythology, Phyge was the as Fuga. The Word "refugium" means spirit of flight, escape, exile and "escape backwards" in Latin, probably in banishment. She was the daughter of reference to a secret exit or a backdoor Ares, the god of war, and Aphrodite, in the houses that allowed to run away the goddess of love. Her brothers in case of emergency. were Phobos (fear) and Deîmos (pain). unicef.es/educa MORE THAN WORDS How is it said refugees in other languages? Spanish: Refugiados Polish: Zarządzanie Korean: 난민 French: Réfugiés Slovak: Utečencov Hindi: शरणार्थी German: Flüchtlingskrise Slovene: Beguncem Icelandic: Flóttafólk טילפ :Dutch:Vluchtelingen Bulgarian: Бежанец Hebrew Italian: Rifugiati Romanian: Refugiaților Swahili: Mkimbizi Swedish: Flyktingkrisen Croatian: Izbjeglicama Kurdish: Penaberên Portuguese:Refugiados Catalan: Refugiats Japanese: 難民 Finnish: Pakolaiskriisin Danish: Flygtninge Quechuan: Ayqiq Greek: Πρόσφυγας Basque: Iheslari Russian: Беженцы Czech: Uprchlická Galician: Refuxiados Somali: Qaxooti Estonian: Pagulas Norwegian: Flyktninger Turkish: Mülteci ںیزگ ہانپ :Urdu ئجال :Hungarian: Menekültügyi Arabic Lithuanian: Pabėgėlių Welch: Ffoadur Chinese: 难民 Vietnamese: -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

6 Confronting Backlash Against Women's Rights And

CONFRONTING BACKLASH AGAINST WOMEN’S RIGHTS AND GENDER 1 EQUALITY IN BRAZIL: A LITERATURE REVIEW AND PROPOSAL Cecilia M. B. Sardenberg 2 Maíra Kubik Mano 3 Teresa Sacchet 4 ABSTRACT: This work is part of a research and intervention programme to investigate, confront and reverse the backlash against gender equality and women’s rights in Brazil, which will be part of the Institute of Development Studies – IDS Countering Backlash Programme, supported by the Swedish International Development Agency - SIDA. This Programme was elaborated in response to the backlash against women's rights and gender equality that has emerged as a growing trend, championed by conservative and authoritarian movements gaining space across the globe, particularly during the last decade. In Brazil, this backlash has been identified as part of an ‘anti-gender’ wave, which has spread considerably since the 2014 presidential elections. Significant changes in Brazil have not only echoed strongly on issues regarding women’s rights and gender justice, but also brought disputes over gender and sexuality to the political arena. To better address the issues at hand in this work, we will contextualize them in their historical background. We will begin with a recapitulation of the re-democratization process, in the 1980s, when feminist and women’s movements emerged as a political force demanding to be heard. We will then look at the gains made during what we here term “the progressive decades for human and women’s rights”, focusing, in particular, on those regarding the confrontation of Gender Based Violence (GBV) in Brazil, which stands as one of the major problems faced by women and LGBTTQIs, aggravated in the current moment of Covid-19 pandemic. -

JULIANNE “JUJU” WATERS Choreographer

JULIANNE “JUJU” WATERS Choreographer COMMERCIAL CHOREOGRAPHY EXPENSIFY // Expensify This // Dir: Andreas Nilsson KLARNA // The Coronation of Smooth Dogg // Dir: Traktor Frontier // Dream Job // Dir: The Perlorian Wish // Amazing Things // Dir: Filip Engstrom Vitamin Water // Drink Outside the Lines // Dir: Traktor Old Navy // Holiyay, Rockstar Jeans // Dir: Joel Kefali Money Supermarket // Bootylicious // Dir: Fredrik Bond LG // Jason Stathum // Dir: Fredrik Bond Dannon // Stayin Alive // Dir: Fredrik Bond Ritz // Putting on the Ritz // Dir: Fredrik Bond FILM Bring It On Cinco // Dir:Billy Woodruff American Carol // Dir: David Zucker Spring Breakdown // Dir: Ryan Shiraki A Cinderella Story// Dir: M. Rosman Bring It On Again // Dir: D. Santostafano TELEVISION Super Bowl XXXVIII // JANET JACKSON feat. JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE Super Bowl XLV // THE BLACK EYED PEAS feat. USHER Fashion Rocks // “Candyman” // CHRISTINA AGUILERA Good Morning America // “Touch my Body” & “That Chick” // MARIAH CAREY Good Morning America // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Soul Train Awards // "I Like The Way You Move" // OUTKAST feat. SLEEPY BROWN Dancing with the Stars // KYLIE MINOGUE Dancing with the Stars // FATIMA ROBINSON TRIBUTE American Music Awards // 2009, 2010, 2011 // THE BLACK EYED PEAS American Music Awards // “Better in Time” // LEONA LEWIS American Music Awards // “Fergalicious” // FERGIE American Music Awards // "Lights, Camera, Action" // P DIDDY feat. MR. CHEEKS & SNOOP DOGG Teen Choice Awards // "Promiscuous" // NELLY FURTATO feat. TIMBERLAND Teen Nick // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Billboard Music Awards // “Fergilicious” // FERGIE VH1 Big in ’06 // “London Bridge & Fergilicious” // FERGIE VIBE Music Awards // “This is How We Do” // THE GAME & 50 CENT Ellen Show // Special Birthday Performance // ELLEN DEGENERES Ellen Show // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Jay Leno // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Jay Leno // "She Bangs" // WILLIAM HUNG Jimmey Kimmel // “With Love & Stranger” // HILARY DUFF BET Awards // “Come Watch Me” // JILL SCOTT feat. -

Handmad So Fabri Hair Roller N Hea Roller an Hair

Wash and Care: Safety Notice: Machine wash in a laundry bag or knotted Our products have an inner layer of PCM pillowcase. and should not be heated prior to use. Lay flat to air dry. Plastic snap pieces can become a choking hazard if placed in the mouth. Keep away from children and pets. You can use styling gels with our products. Wipe with a damp cloth between washing On occasion, through normal usage, a to reduce product buildup. snap may disengage or break completely Do not store satin products with Velcro to from your roller. Should this happen please avoid snags. contact us at [email protected]. In most instances we can replace a broken snap. We require that you send your original roller/bun to us. We will pay postage for returning your roller to you after we replace your snaps. Handmad So Fabri Hair Roller N Hea Roller an Hair Bun You can slide all of your hair around and How Our Rollers Work My Easy Curls Rollers completely cover the roller or leave Our rollers are equipped with Phase Wind small section of slightly damp hair part of the roller showing and wear as a Change Material (PCM). Essentially, it’s around each roller and snap the ends fashion accessory. Secure with bobby pins heat managing fabric. This unique material together. if needed. oers both an extra layer of durability for our handmade rollers and draws excess Continue winding small sections of hair One inch and One-one-half inch rollers are heat from your hair into the roller. -

SYO Hair Salon 2E Compiled.Pdf

Entrepreneur Press, Publisher Cover Design: Jane Maramba Production and Composition: Eliot House Productions © 2012 by Entrepreneur Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work beyond that permitted by Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act without permission of the copyright owner is unlawful. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to the Business Products Division, Entrepreneur Media Inc. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting or other professional services. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Hair Salon & Day Spa: Entrepreneur’s Step-by-Step Startup Guide, 2nd Edition, ISBN: 978-1-59918-473-9 Previously published as Start Your Own Hair Salon & Day Spa, 2nd Edition, ISBN: 978-1-59918-346-6, © 2010 by Entrepreneur Media, Inc., All rights reserved. Start Your Own Business, 5th Edition, ISBN: 978-1-59918-387-9, © 2009 Entrepreneur Media, Inc., All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Preface. xiii Chapter 1 Hair Today, Hair Tomorrow . 1 Earning Potential . 2 A Look Back . 3 A Look Forward. 3 The Opportunities . 4 Chapter 2 The Salon Scene . 7 Chop Shop . 8 Selecting Services. 8 Smoothing and Soothing . 10 Beauty Business Basics . 12 A Day in the Life . -

Pdf) on the World District, 26 Federal Plaza, New York, Administration National Capital Region, Wide Web at Either of the Following NY 10278–0090

3±24±98 Tuesday Vol. 63 No. 56 March 24, 1998 Pages 14019±14328 Briefings on how to use the Federal Register For information on briefings in Washington, DC, and Salt Lake City, UT, see announcement on the inside cover of this issue. Now Available Online via GPO Access Free online access to the official editions of the Federal Register, the Code of Federal Regulations and other Federal Register publications is available on GPO Access, a service of the U.S. Government Printing Office at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/index.html For additional information on GPO Access products, services and access methods, see page II or contact the GPO Access User Support Team via: ★ Phone: toll-free: 1-888-293-6498 ★ Email: [email protected] federal register 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 56 / Tuesday, March 24, 1998 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES PUBLIC Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 General online information 202±512±1530; 1±888±293±6498 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), Single copies/back copies: by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Paper or fiche 512±1800 Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Assistance with public single copies 512±1803 Register Act (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and FEDERAL AGENCIES the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Subscriptions: Register (1 CFR Ch. I). Distribution is made only by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S.