Whereabouts Are We?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Équipes Présentes Aux GPCQM 2012

LES ÉQUIPES PARTICIPANTES AUX GRANDS PRIX CYCLISTES DE QUÉBEC ET DE MONTRÉAL 2012 I- PROTEAMS (18) AG2R LA MONDIALE (FRANCE) L’équipe dirigée par Vincent Lavenu est la plus ancienne du peloton français. Si elle souffre d’un manque chronique de victoires, elle s’assure en général une belle présence au classement général des courses par étapes. Privée de ses leaders Roche et Péraud, elle comptera au Canada sur la pointe de vitesse du Suisse Elmiger et sur ses jeunes talents. Date de création : 1992 Victoires 2012 : 4 (au 14 août) LES HOMMES À SUIVRE Martin ELMIGER (SuissE) : 33 ans, professionnel depuis 2001 Palmarès : 12 victoires dont au 4 Jours de Dunkerque 2010 Cette saison : 3e championnat de Suisse contre-la-montre Capitaine de route de la formation tricolore, en partance pour la nouvelle équipe helvète IAM, le Suisse a souvent su faire valoir ses qualités de finisseurs sur le final des courses sélectives. Il sera le plus expérimenté des coureurs d’AG2R sur les deux épreuves canadiennes. Romain BARDET (FrancE) : 21 ans, professionnel depuis 2012 Palmarès : néant Cette saison : 5e Tour de Turquie C’est l’un des Français les plus prometteurs de sa génération. Dès sa première année professionnelle, il a su trouver ses marques dans le peloton et compiler quelques beaux résultats. Ses qualités de grimpeur devraient encore s’affirmer à l’avenir. ASTANA (KAZAKHSTAN) Créée pour et par Alexandre Vinokourov, l’enfant vedette du pays tout récent champion olympique, la formation kazakhe qui porte le nom de la capitale, financée par un conglomérat pétrolier, brille depuis cinq ans au plus haut niveau. -

Cycling Australia Annual Report

2 CYCLING AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2020 CONTENTS Sponsors and Partners 4 - 5 Board/Executive Team 6 Sport Australia Message 7 Strategic Overview 8 One Sport 9 Chair’s Report 10 - 11 CEO's Message 12 - 13 Australian Cycling Team 14 - 25 Commonwealth Games Australia Report 26 - 27 Sport 28 - 29 Participation 30 - 33 AUSTRALIA CYCLING Membership 34 - 37 Media and Communications 38 - 39 Corporate Governance 40 - 41 Anti-doping 42 - 43 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 REPORT ANNUAL Technical Commission 44 - 45 Financial Report 46 - 70 State Associations 72 - 89 Cycling ACT 72 - 73 Cycling NSW 74 - 75 Cycling NT 76 - 77 Cycling QLD 78 - 79 Cycling SA 80 - 81 Cycling TAS 82 - 85 Cycling VIC 86 - 87 WestCycle 88 - 89 World Results 90 - 97 Australian Results 98 - 113 Team Listings 114 - 115 Office Bearers and Staff 116 - 119 Honour Roll 120 - 122 Award Winners 123 PHOTOGRAPHY CREDITS: Craig Dutton, Casey Gibson, Con Chronis, ASO, John Veage, UCI, Steve Spencer, Commonwealth Games Australia, Adobe Stock 3 PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY PRINCIPAL PARTNERS SPORT PARTNERS ANNUAL REPORT 2020 REPORT ANNUAL MAJOR PARTNERS CYCLING AUSTRALIA CYCLING BROADCAST PARTNERS 4 PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY EVENT PARTNERS CYCLING AUSTRALIA CYCLING ANNUAL REPORT 2020 REPORT ANNUAL SUPPORTERS Cycling Australia acknowledges Juilliard Group for support in the provision of the CA Melbourne Office 5 BOARD AND EXECUTIVE TEAM AS AT 30 SEPTEMBER 2020 CYCLING AUSTRALIA BOARD DUNCAN MURRAY STEVE DRAKE LINDA EVANS Chair Managing Director Director ANNUAL REPORT 2020 REPORT ANNUAL ANNE GRIPPER GLEN PEARSALL PENNY SHIELD Director Director Director EXECUTIVE TEAM CYCLING AUSTRALIA CYCLING STEVE DRAKE JOHN MCDONOUGH KIPP KAUFMANN Chief Executive Officer Chief Operating Officer General Manager and Company Secretary Sport SIMON JONES NICOLE ADAMSON Performance Director, General Manager Australian Cycling Team Participation and Member Services 6 Message from Sport Australia The start of 2020 has been an extraordinarily tough time for Australians, including all of us committed to sport. -

University of Groningen Between Personal Experience and Detached

University of Groningen Between personal experience and detached information Harbers, Frank IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Harbers, F. (2014). Between personal experience and detached information: The development of reporting and the reportage in Great Britain, the Netherlands and France, 1880-2005. [S.l.]: [S.n.]. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 Paranymphs Dominique van der Wal Marten Harbers Voor mijn vader en mijn moeder Graphic design Peter Boersma - www.hehallo.nl Printed by Wöhrmann Print Service Between Personal Experience and Detached Information The development of reporting and the reportage in Great Britain, the Netherlands and France, 1880-2005 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. -

Presentacion

PRESENTACION TRAS EL EXITO DE LAS DOS EDICIONES PASADAS, EN 2011 SE VOLVIA A ORGANIZAR LA COPA CAJA RURAL BTT DE MANOS DE LOS CLUBES NAVARROS ITURROTZ, SALTAMONTES, 39X26, BARCELOSA Y CUATRO CAMINOS, CONSOLIDANDO ESTA COMO UNA DE LAS MAS IMPORTANTES DE ESPAÑA. SU IMPECABLE ORGANIZACIÓN, Y EL ALTO NIVEL DEPORTIVO QUE HAN CARACTERIZADO LAS OCHO PRUEBAS HA TRASPASADO LAS FRONTERAS DE NUESTRA COMUNIDAD, ATRAIENDO TANTO A PARTICIPANTES COMO MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN DE NIVEL NACIONAL. DESTACAR LA VISITA EN ALGUNAS PRUEBAS DE CORREDORES PROFESIONALES, SELECCIONES AUTONOMICAS Y/O EQUIPOS DE ELITE DE OTRAS COMUNIDADES QUE HAN ELEGIDO LAS PRUEBAS DE NUESTRA COPA PARA COMPLETAR SUS CALENDARIOS, MUESTRA INEQUIVOCA DE LA BUENA LABOR QUE SE ESTA HACIENDO DESDE LA ORGANIZACIÓN Y LA POSICION QUE OCUPAN NUESTRAS PRUEBAS EN EL CALENDARIO NACIONAL. ADEMAS, DESDE LA ORGANIZACIÓN SE HA HECHO UN GRAN ESFUERZO EN LA DIVULGACION DE LA COPA NO SOLO ENTRE EL PUBLICO ESPECIALIZADO, SINO TAMBIEN ENTRE EL PUBLICO EN GENERAL, INTENTANDO ACERCAR LAS PRUEBAS A LOS NUCLEOS URBANOS MAS IMPORTANTES DE NAVARRA, ESTRENANDO COMO SEDES EN 2010 SANGÜESA, Y EN ESTE 2011 TAFALLA, Y CON LA INTENCION DE SEGUIR ESTA DINAMICA EN AÑOS VENIDEROS DE CARA A HACER NUESTRO DEPORTE Y TORNEO MAS GRANDES SI CABE. TODO ESTO SIN OLVIDAR A LA CANTERA. TRABAJANDO CON LOS AYUNTAMIENTOS Y COLEGIOS LOCALES, SE HA CONSEGUIDO SUBIR NOTABLEMENTE LA PARTICIPACION DE NIÑOS Y NIÑAS LOCALES EN LA CARRERA QUE HACEMOS PARALELA PARA LAS ESCUELAS, IMPLICANDO EN MAYOR MEDIDA AL PUEBLO QUE ACOGE LA PRUEBA, Y CONSIGUIENDO ASI UNA REPERCUSION MUCHO MAYOR EN ESTE. EN LAS SIGUIENTES PAGINAS PODRA ENCONTRAR UN RESUMEN DE LO ACONTECIDO EN LA COPA CAJA RURAL BTT 2011. -

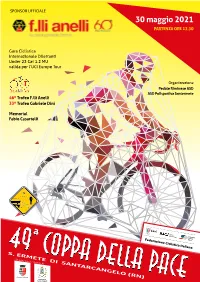

30 Maggio 2021 PARTENZA ORE 13,30

30 maggio 2021 PARTENZA ORE 13,30 Gara Ciclistica Internazionale Dilettanti Under 23 Cat 1.2 MU valida per l’UCI Europe Tour Organizzazione Pedale Riminese ASD ASD Polisportiva Santermete 46º Trofeo F.lli Anelli 33º Trofeo Gabriele Dini Memorial Fabio Casartelli UNION CYCLISTE a INTERNATIONALE Federazione Ciclistica 49 Federazione Ciclistica ItalianaItaliana S. ERMETE COPPA DI SANTARCANGELO DELLA (RN) PACE Col patrocinio del Comune di: Coppa della Pace 2021 1 Comune di Santarcangelo 2 Coppa della Pace 2021 La vittoria così come il raggiungimento di ogni obiettivo nella vita, non sono solo un momento, ma il risultato di un percorso, Speciale SQUADRE condiviso con molti, fatto spesso di fatica, battute d’arresto, dedizione, momenti difficili Cerca tutte le foto delle ed altri entusiasmanti. Fedele al suo spirito di formazioni, che hanno sostegno ai valori dello sport e con immutata partecipato nel 2019!"Foto Soncini" fiducia nel futuro, torna così la Coppa della INDICE Pace- Trofeo Fratelli Anelli. Un traguardo possibile grazie a tutti coloro che permet- Saluti degli organizzatori 5 tono di raggiungerlo. Per questo il Pedale Riminese e la Polisportiva Sant’Ermete, quali Bruno Anelli 7 organizzatori della 49^ Coppa della Pace Saluti 8/10 – 46° Trofeo F.lli Anelli, gara internazionale Dilettanti, Under 23 categoria 1.2 MU, valida Con una grande passione, puoi per l’UCI Europe Tour, Trofeo Gabriele Dini, costruire anche una grande azienda 28 trofeo Capello d’Oro e Memorial Fabio Ca- sartelli, si uniscono per esprimere il loro più Percorso 38/40 sentito grazie. Disposizioni 41 Grazie per l’affetto, la dedizione, l’impegno Descrizione del percorso 41 e la generosità che tutti i volontari, le forze dell’ordine, gli addetti alla sicurezza e al soc- Dal mare e dalla terra, piccoli e corso, gli enti, le autorità, i tecnici e le realtà preziosi doni per salute e gusto 47 economiche rinnovano anche in quest’anno così complesso, per il successo e la realiz- Albo d’oro 55 zazione della Coppa della Pace. -

'Life Goes On' for NBC Sports's Tour Team

The Outer Line The External Perspective On Pro Cycling ‘Life Goeshttps://www.theouterline.com on’ for NBC Sports’s Tour Team Following Sherwen’s Tragic Death When the Tour de France coverage kicks off on NBC Sports Network this weekend, it will mark the first time in 33 years that an English speaking audience will not hear the voice and sage insights of Paul Sherwen, who passed away in December, 2018. Long-time insider and supporting desk presenter Bob Roll will join the venerable Phil Liggett in front of the live commentary box cameras when coverage starts from Brussels, Belgium, Saturday, July 6. The transition would appear natural in light of Roll’s veteran experience in the booth and rapport with both personalities, and his deep historical cycling knowledge. Behind the scenes, NBC faces a daunting task to elevate its production game due to the expected impacts of Sherwen’s absence. “Bob knows he can never fill Paul’s shoes. Bob will simply have to cobble together a new pair,” said NBC’s Producer David Michaels, who has helmed the Tour’s American telecast since 2011. “Bob’s had a bit of experience working mano à mano with Phil. He brings a different energy and perspective. Bob grows with each broadcast. Can’t think of anyone out there who could go hour upon hour alongside Phil except Bob.” Michaels has an unprecedented perspective on his side. He began his storytelling of the Tour de France in the mid-1980s with CBS (his brother, Al, is widely known for his work in rival network ABC) and helped bring Greg LeMond’s famous 1985 and 1986 duels with teammate Bernard Hinault to the American audience. -

Activity Report 2017

Activity Report 2017 LDA Mostar activities aim to create active citizenship and transparent and responsible authorities with the final goal of establishing a modern and democratic society… Local Democracy Agency Mostar WWW.LDAMOSTAR.ORG| Fra Ambre Miletica 30, 88 000 Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina 1 Activity Report 2017 2 Activity Report 2017 Contents About ............................................................................................................................ 4 PROJECTS IMPLEMENTED IN 2017 ............................................................................ 8 Balkan Regional Platform for Youth Participation and Dialogue .................................. 8 Urban Re-Generation: The European Network of Towns - URGENT ........................ 22 CARAVAN NEXT. Feed the Future: Art Moving Cities ............................................... 27 Innovating COworking Methods through Exchange – INCOME ................................. 29 Balkan Kaleidoscope ................................................................................................. 31 Women's Communication for Solidarity - WomCom .................................................. 33 Youth’s Advocate - YouAct ........................................................................................ 35 Volunteer Management in Europe's Youth Sector - VOLS EUROPE ........................ 36 Snapshots from the Borders - Small Towns Facing the Global Challenges of Agenda 2030 .......................................................................................................................... -

EL MUNDO Biografía No Autorizada De Alberto Contador (Solomillo

EL MUNDO Biografía no autorizada de Alberto Contador (solomillo incluido) 7/08/2017 Luis Fernando López Podría ocurrir: Alberto Contador, en su última carrera y en su último día, el próximo 10 de septiembre, sube al podio final de la Vuelta a España y el público le abuchea. Podría ocurrir, pero no va a ocurrir; no veremos a Contador sufrir una escena como las vividas estos días en el Mundial de atletismo, donde el público ha despreciado a Gatlin por su pasado de dopaje con recurrentes pitadas (el silencio a veces es más sonoro). No es el público español más respetuoso que el inglés, no, pues también aquí gusta mucho silbar; basta repasar las finales de Copa del Rey, el cariño que una parte de la grada le dispensa a Piqué cuando acude con la selección o algunas sinfonías antes de partidos de La Roja (oé, oé). Pero a Contador no se le pitará. Madrid/España no es Londres. Y bien está. Pero, ¿le aplaudimos como si nada? Más preguntas: ¿Tiene derecho al perdón quien se ha dopado? Si somos capaces de 'olvidar' crímenes u ofensas mayores, ¿por qué no íbamos a hacerlo con un deportista que se equivocó/nos engañó una vez? Pero, claro, depende. ¿Cuántas veces se equivocó y nos engañó Contador? Una noche de julio de 2006, apenas un mes después de ser detenido en la 'operación Puerto' como cabecilla de una trama de dopaje, Eufemiano Fuentes, un 'teórico' de las autotransfusiones con EPO, acudió a 'El Larguero' para explicarse, al fin. De lo que dijo, a quien esto escribe, que es periodista pero no de los especializados en ciclismo, le sorprendió algo. -

Vinokourov.Pdf

>> La preuve par 21 Alexander Vinokourov Alexander VINOKOUROV Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. A 1’42s à Mayo qui bat le record du Ventoux 425 6,25 435 00:57:33 1 « La belle histoire » 1er-26 ans Tour de France 1999 Sestrières. Il termine à plus de 34min d’Armstrong X 5 35ème-26 ans Alpe d’Huez 379 5,57 383 00:43:33 3 Team Casino Piau Engaly.Il termine à plus de 36min d’Escartin vainqueur X 5 Soulor et Aubisque.4è tape, présent dans l’échappée matinale X 3 Tour de France 2000 Hautacam.Lâchè dès l’Aubisque X 3 15ème-27 ans Ventoux 379 5,57 384 00:52:22 1 Team Deutsche Telekom Izoard. Ne perd qu’une minute sur Armstrong et Pantani 413 6,07 418 00:33:27 3 Courchevel. Distancé, il termine à 22 minutes de Pantani X 3 Joux Plane X 4 2ème des Jeux oympiques de Sydney à la sortie du Tour avec un «Triplé» Telekom Tour de France 2001 Alpe d’Huez. Termine à 11 minutes de Lance Armstrong 328 4,82 335 00:49:00 3 16ème-28 ans Chamrousse CLM 400 5,88 409 00:50:42 1 Bonascre 391 5,75 400 00:24:27 3 Pla d’Adet. Echappé en cours d’étape avec Jalabert X 6 Luz-Ardiden X 3 Chute au Tour de Suisse 2002 Tour d’Espagne 2002 Sierra Nevada. 5ème de l’étape X Non partant 11ème étape-29 ans La Pandera. -

Great Ridesgreat Deck It Was On

D E T A I L S WHERE: Brittany, France START/FINISH: St Malo to Roscoff DISTANCE: 235 miles PICTURES: Getty Images and Caroline Burrows BRITTANY | GREAT RIDES Great rides CYCLING BACK TO HAPPINESS Despite a car driver’s carelessness damaging her bike, body, and self-confi dence, Caroline Burrows pressed ahead with her planned tour of Brittany t New Year I made a resolution I was woken by Brittany Ferries piping Do it yourself to have lots of mini-adventures, music into the cabin around 6am, and an hour so booked a ferry to France for a later was untying my bike to a morning chorus TRAINS A week’s cycling tour in the summer. of engines. The car deck doors opened to AND FERRIES The next day a car drove into me at a sunshine. Soon I was sipping an overpriced junction. It was an odd experience travelling but delicious latte outside a café within the I took my bike by train from Bristol to Portsmouth, and backwards on a bonnet, aware that this grey, granite walls of St Malo. back from Plymouth to Bristol, might be it – the end. I survived. Whether I’d with Great Western Railway. recover in time for my trip was, just as I had ON THE GREENWAYS Their website (gwr.com) lets been during the crash, up in the air. My tour proper began at Dinard, a 15-minute you make bike reservations online at the same time as May arrived. I was still having physio for journey away on a local Corsaire ferry. -

2014 Amgen Tour of California Team Rosters Announced

2014 AMGEN TOUR OF CALIFORNIA TEAM ROSTERS ANNOUNCED Field of 128 Elite Cyclists Will Include Tour de France Champion; Three of World’s Top-10 Cyclists; Six of World’s Top-10 Teams LOS ANGELES (May 5, 2014) – The start list for the 2014 Amgen Tour of California was announced today by AEG, presenter of the race. With 128 riders from 16 elite professional cycling teams, the Amgen Tour of California is the most esteemed stage race in the U.S. and one of the most important on the international calendar. With experts already predicting the 2014 edition will host the ninth annual event’s strongest and most competitive field to date, the race begins Sunday, May 11, and will include three of the world’s top-10 cyclists; Tour de France, Giro de Italia and Vuelta a España (Grand Tours) podium finishers; Olympic medalists; 10 World Champions; and six current National Champions, as well as exciting up-and-coming talent. All will be competing to take top honors in America’s most prestigious cycling race across more than 720 miles of California’s iconic highways, summits and coastlines May 11-18. “We are honored to welcome such a stellar field of cyclists, many of whom have traveled across the world to compete at the 2014 Amgen Tour of California,” said Kristin Bachochin, executive director of the race and senior vice president of AEG Sports. “We look forward to an exciting race with one the most accomplished fields of riders to date.” The roster of cycling’s best is packed with some of the most decorated cyclists in the world, from Team Sky’s Bradley Wiggins, the first cyclist in history to win Olympic gold and the Tour de France in the same year; to Omega Pharma – Quick-Step’s Mark Cavendish, who holds the third ever most Tour de France stage wins (25); to Cannondale’s Peter Sagan, who holds the record for the most Amgen Tour of California stage wins (10). -

Descargar Libro De Ruta

Consejero de Cultura y Turismo de la Junta de Castilla y León La crisis sanitaria provocada por la Covid-19 ha condicionado nuestras vidas y nuestra actividad diaria. El deporte no ha sido ajeno a esta situación pero, poco a poco, hemos sabido adaptarnos, hemos podido practicarlo y hemos logrado realizar eventos deportivos, con más o menos restricciones, pero intentando siempre no paralizar nuestro deporte. A partir de marzo de 2020, la pandemia provocó la suspensión de muchos eventos cuya preparación estaba en marcha. Uno de ellos fue la Vuelta Ciclista a Castilla y León para ciclistas internacionales. La previsión era dar la salida en el mes de abril, pero, ante la evolución de la situación sanitaria, se decidió no celebrar la prueba a lo largo de 2020. Sin embargo, desde hace meses, se ha venido trabajando en retomar su celebración en 2021, tomando la decisión de realizar una prueba de una etapa, que recorrerá la provincia de León el 29 de julio, con salida en León capital Javier Ortega Álvarez y llegada en Ponferrada. Su recorrido por tierras del Camino de Santiago en este Año Jacobeo, lleno de belleza paisajística y monumental, no dejará indiferentes a los aficionados y, sin duda, animará a visitar esta tierra y a probar la rica y variada gastronomía leonesa y berciana. Este año, la edición será ya la número XXXV y una vez más, contaremos con una prueba de gran nivel deportivo, con varios equipos World Tour y numerosos equipos internacionales, así como con la perfecta organización a la que nos tiene acostumbrados el Club Ciclista Cadalsa.