Graphic Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime

SAN DIEGO PUBLIC LIBRARY PATHFINDER Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, & Anime The Central Library has a large collection of comics, the Usual Extra Rarities, 1935–36 (2005) by George graphic novels, manga, anime, and related movies. The Herriman. 741.5973/HERRIMAN materials listed below are just a small selection of these items, many of which are also available at one or more Lions and Tigers and Crocs, Oh My!: A Pearls before of the 35 branch libraries. Swine Treasury (2006) by Stephan Pastis. GN 741.5973/PASTIS Catalog You can locate books and other items by searching the The War Within: One Step at a Time: A Doonesbury library catalog (www.sandiegolibrary.org) on your Book (2006) by G. B. Trudeau. 741.5973/TRUDEAU home computer or a library computer. Here are a few subject headings that you can search for to find Graphic Novels: additional relevant materials: Alan Moore: Wild Worlds (2007) by Alan Moore. cartoons and comics GN FIC/MOORE comic books, strips, etc. graphic novels Alice in Sunderland (2007) by Bryan Talbot. graphic novels—Japan GN FIC/TALBOT To locate materials by a specific author, use the last The Black Diamond Detective Agency: Containing name followed by the first name (for example, Eisner, Mayhem, Mystery, Romance, Mine Shafts, Bullets, Will) and select “author” from the drop-down list. To Framed as a Graphic Narrative (2007) by Eddie limit your search to a specific type of item, such as DVD, Campbell. GN FIC/CAMPBELL click on the Advanced Catalog Search link and then select from the Type drop-down list. -

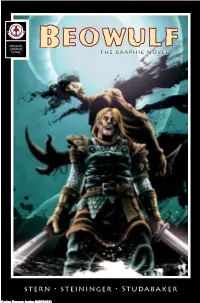

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Graphic Gothic Introduction Julia Round

Graphic Gothic Introduction Julia Round ‘Graphic Gothic’ was the seventh International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference, held at Manchester Metropolitan University in June 2016.1 The event brought together fifty scholars from all over the globe, who explored Gothic under themes such as setting, politics, adaptation, censorship, monstrosity, gender, and corporeality. This issue of Studies in Comics collects selected papers from the conference, alongside expanded versions of the talks given by three of our four keynote speakers: Hannah Berry, Toni Fejzula and Matt Green. It is complemented by a comics section that recalls the conference and reflects the potential of Gothic to inform and inspire as Paul Fisher Davies provides a sketchnoted diary of the event. Defining the Gothic is a difficult task. Baldick and Mighall (2012: 273) note that much of the relevant scholarship to date has primarily applied ‘the broadest kind of negation: the Gothic is cast as the opposite of Enlightenment reason, as it is the opposite of bourgeois literary realism.’ Moers also suggests that the meaning of Gothic ‘is not so easily stated except that it has to do with fear’ (1978: 90). Many Gothic scholars and writers have explored the nature of this fear: attempting to draw out and categorise the metaphorical meanings and affect it can create. H.P. Lovecraft (1927: 41) claims that ‘The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind fear of the unknown’ (Lovecraft 1927: 41) and that this is the basis for ‘the weirdly horrible tale’ as a literary form. Ann Radcliffe (1826: 5) famously separates terror and horror, and later writers and critics such as Devendra Varma (1957), Robert Hume (1969), Stephen King (1981), Gina Wisker and Dale Townshend continue to explore this divide. -

GRAPHIC NOVELS in ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: a PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater a Dissertation Submi

GRAPHIC NOVELS IN ADVANCED ENGLISH/LANGUAGE ARTS CLASSROOMS: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL CASE STUDY Cary Gillenwater A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Madeleine Grumet James Trier Jeff Greene Lucila Vargas Renee Hobbs © 2012 Cary Gillenwater ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CARY GILLENWATER: Graphic novels in advanced English/language arts classrooms: A phenomenological case study (Under the direction of Madeleine Grumet) This dissertation is a phenomenological case study of two 12th grade English/language arts (ELA) classrooms where teachers used graphic novels with their advanced students. The primary purpose of this case study was to gain insight into the phenomenon of using graphic novels with these students—a research area that is currently limited. Literature from a variety of disciplines was compared and contrasted with observations, interviews, questionnaires, and structured think-aloud activities for this purpose. The following questions guided the study: (1) What are the prevailing attitudes/opinions held by the ELA teachers who use graphic novels and their students about this medium? (2) What interests do the students have that connect to the phenomenon of comic book/graphic novel reading? (3) How do the teachers and the students make meaning from graphic novels? The findings generally affirmed previous scholarship that the medium of comic books/graphic novels can play a beneficial role in ELA classrooms, encouraging student involvement and ownership of texts and their visual literacy development. The findings also confirmed, however, that teachers must first conceive of literacy as more than just reading and writing phonetic texts if the use of the medium is to be more than just secondary to traditional literacy. -

V for Vendetta’: Book and Film

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro Dissertação orientada por Doutora Teresa Cid MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 Abstract The current work seeks to contrast the book version of Alan Moore and David Lloyd‟s V for Vendetta (1981-1988) with its cinematic counterpart produced by the Wachowski brothers and directed by James McTeigue (2005). This dissertation looks at these two forms of the same enunciation and attempts to analise them both as cultural artifacts that belong to a specific time and place and as pseudo-political manifestos which extemporize to form a plethora of alternative actions and reactions. Whilst the former was written/drawn during the Thatcher years, the film adaptation has claimed the work as a herald for an alternative viewpoint thus pitting the original intent of the book with the sociological events of post 9/11 United States. Taking the original text as a basis for contrast, I have relied also on Professor James Keller‟s work V for Vendetta as Cultural Pastiche with which to enunciate what I consider to be lacunae in the film interpretation and to understand the reasons for the alterations undertaken from the book to the screen version. An attempt has also been made to correlate Alan Moore‟s original influences into the medium of a film made with a completely different political and cultural agenda. -

Manga As a Teaching Tool 1

Manga as a Teaching Tool 1 Manga as a Teaching Tool: Comic Books Without Borders Ikue Kunai, California State University, East Bay Clarissa C. S. Ryan, California State University, East Bay Proceedings of the CATESOL State Conference, 2007 Manga as a Teaching Tool 2 Manga as a Teaching Tool: Comic Books Without Borders The [manga] titles are flying off the shelves. Students who were not interested in EFL have suddenly become avid readers ...students get hooked and read [a] whole series within days. (E. Kane, personal communication, January 17, 2007) For Americans, it may be difficult to comprehend the prominence of manga, or comic books, East Asia.1. Most East Asian nations both produce their own comics and publish translated Japanese manga, so Japanese publications are popular across the region and beyond. Japan is well-known as a highly literate society; what is less well-known is the role that manga plays in Japanese text consumption (Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco). 37% of all publications sold in Japan are manga of one form or another, including monthly magazines, collections, etc. (Japan External Trade Organization [JETRO], 2006). Although Japan has less than half the population of the United States, manga in all formats amounted to sales within Japan of around 4 billion dollars in 2005 (JETRO, 2006). This total is about seven times the United States' 2005 total comic book, manga, and graphic novel sales of 565 million dollars (Publisher's Weekly, 2007a, 2007b). Additionally, manga is closely connected to the Japanese animation industry, as most anime2 television series and films are based on manga; manga also provides inspiration for Japan's thriving video game industry. -

Brianna J. Leesch. the Graphic Novel Ratings Game: Publisher Ratings and Librarian Self-Rating

Brianna J. Leesch. The Graphic Novel Ratings Game: Publisher Ratings and Librarian Self-rating. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2013. 62 pages. Advisor: Brian Sturm Graphic materials such as comic books, graphic novels and manga are an expanding section within most library collections. This study defines graphic materials and examines the role of ratings systems and subjective rating assignment by librarians in the acquisition and collection process. While publishers of such graphic materials provide rating systems for librarians to use when making acquisition and placement decisions, these rating systems are not uniform. This leads to the librarian relying upon professional judgment along with review resources and knowledge of the community served by the library. The author has concluded that librarians self-rate graphic materials consistent with the publisher ratings 50% of the time. Data also shows that a further 30% of the time librarians will rate graphic materials for a younger age than the publishers. Misplacement in the public library, according to the interview information, is a rare occurrence. Headings: Graphic novels Age-rating Public library Placement THE GRAPHIC NOVEL RATINGS GAME: PUBLISHER RATINGS AND LIBRARIAN SELF-RATING by Brianna J. Leesch A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina April 2013 Approved by _______________________________________ Brian Sturm 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………………2 "Ratings Game" Comic Introduction by Daena Vogt-Lowell…………………………………....3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... -

Overthrowing Vengeance: the Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta

Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta Pedro Moreira University of Porto, Portugal Citation: Pedro Moreira, ”Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta ”, Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal , nr. 4, Spring 2007, pp. 106-112 <http://ler.letras.up.pt > ISSN 1646-4729. Introduction The emergence of the critical dystopia genre in the 1980s allowed for the appearance of a body of literature capable of both informing and prompting readers to action. The open-endness of these works, coupled with the sense of critique, becomes a key element in performing a catalyst function and maintaining hope within the text. V for Vendetta , by Alan Moore, with illustrations by David Lloyd, first published in serial form between 1982 and 1988 and, later, in 1990, as a graphic novel is one of such works. Appearing during the political climate of Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, it became a cult classic amongst graphic novels readers and collectors. A film adaptation was released in 2006, from a screenplay by the Wachowski brothers, to different reactions from the graphic novel’s creators; Moore withdrew his support and denied any involvement in the adaptation while David Lloyd publicly confessed his admiration for the movie. I first became interested in the series due to its gritty realism, and the enigmatic, cultured figure of the protagonist. In fact, V for Vendetta ’s universe is quite distant from the comic book genre, which is dominated by God-like figures such as Superman or Spiderman. Also, the sheer scope of reference in the work, ranging from Blake and Shakespeare to the Rolling Stones and The Velvet Underground, added to my interest, making it the subject of this paper. -

Graphic Novel Titles

Comics & Libraries : A No-Fear Graphic Novel Reader's Advisory Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives February 2017 Beginning Readers Series Toon Books Phonics Comics My First Graphic Novel School Age Titles • Babymouse – Jennifer & Matthew Holm • Squish – Jennifer & Matthew Holm School Age Titles – TV • Disney Fairies • Adventure Time • My Little Pony • Power Rangers • Winx Club • Pokemon • Avatar, the Last Airbender • Ben 10 School Age Titles Smile Giants Beware Bone : Out from Boneville Big Nate Out Loud Amulet The Babysitters Club Bird Boy Aw Yeah Comics Phoebe and Her Unicorn A Wrinkle in Time School Age – Non-Fiction Jay-Z, Hip Hop Icon Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain The Donner Party The Secret Lives of Plants Bud : the 1st Dog to Cross the United States Zombies and Forces and Motion School Age – Science Titles Graphic Library series Science Comics Popular Adaptations The Lightning Thief – Rick Riordan The Red Pyramid – Rick Riordan The Recruit – Robert Muchamore The Nature of Wonder – Frank Beddor The Graveyard Book – Neil Gaiman Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs House of Night – P.C. Cast Vampire Academy – Richelle Mead Legend – Marie Lu Uglies – Scott Westerfeld Graphic Biographies Maus / Art Spiegelman Anne Frank : the Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography Johnny Cash : I See a Darkness Peanut – Ayun Halliday and Paul Hope Persepolis / Marjane Satrapi Tomboy / Liz Prince My Friend Dahmer / Derf Backderf Yummy : The Last Days of a Southside Shorty -

Alan Moore V for Vendetta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons Early draft of essay eventually published in Sexual Ideology in the Works of Alan Moore Comer 1 “Body Politics: Unearthing an Embodied Ethics in V for Vendetta” Todd A. Comer In light of the oft-made allegation that superheroes are in many respects carbon copies of the fascist world that they were consciously or unconsciously intended to oppose, V for Vendetta may be Alan Moore’s most direct commentary on the superheroic body and its desires. Intimations of fascism, of course, are everywhere in Moore’s work. The German soldier who shatters Alice’s mirror in Lost Girls, William Gull’s bird-like transcendence in From Hell, Superman’s repression of the too-earthy Swamp Thing in “The Jungle Line,” Moriarty’s cavorite- fueled journey toward heaven (and death) in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen—all speak to Moore’s critique of the superheroic tendency to marginalize the world and others. Moore and David Lloyd’s graphic novel is the most direct commentary on the superhero body if only because the body of the hero and villain are obnoxiously present, even as they strangely absent themselves. The novel appears to ground agency to an embodied totalitarian world in terms of (dis)embodiment. Agency is, of course, an issue of the body and its representation, but Moore and Lloyd get it wrong, at least on one overt level, by misunderstanding the ultimate goal of fascism and reproducing a notion of agency that merely reproduces on another level the (ontological) state that it presumes to counter. -

Writing About Comics

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators English 100-v: Writing about Comics From the wild assertions of Unbreakable and the sudden popularity of films adapted from comics (not just Spider-Man or Daredevil, but Ghost World and From Hell), to the abrupt appearance of Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman all over The New Yorker, interesting claims are now being made about the value of comics and comic books. Are they the visible articulation of some unconscious knowledge or desire -- No, probably not. Are they the new literature of the twenty-first century -- Possibly, possibly... This course offers a reading survey of the best comics of the past twenty years (sometimes called “graphic novels”), and supplies the skills for reading comics critically in terms not only of what they say (which is easy) but of how they say it (which takes some thinking). More importantly than the fact that comics will be touching off all of our conversations, however, this is a course in writing critically: in building an argument, in gathering and organizing literary evidence, and in capturing and retaining the reader's interest (and your own). Don't assume this will be easy, just because we're reading comics. We'll be working hard this semester, doing a lot of reading and plenty of writing. The good news is that it should all be interesting. The texts are all really good books, though you may find you don't like them all equally well. The essays, too, will be guided by your own interest in the texts, and by the end of the course you'll be exploring the unmapped territory of literary comics on your own, following your own nose.