Be Independent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

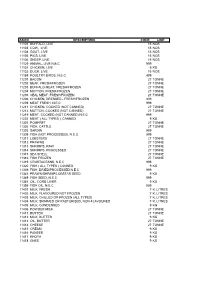

Asicc Description Code Unit 11101 Buffalo, Live 15 Nos

ASICC DESCRIPTION CODE UNIT 11101 BUFFALO, LIVE 15 NOS 11103 COW, LIVE 15 NOS 11104 GOAT, LIVE 15 NOS 11105 PIGS, LIVE 15 NOS 11106 SHEEP, LIVE 15 NOS 11129 ANIMAL, LIVE N.E.C 999 11131 CHICKEN, LIVE 9 KG 11132 DUCK, LIVE 15 NOS 11159 POULTRY BIRDS, N.E.C 999 11201 BACON 27 TONNE 11202 BEAF, FRESH/FROZEN 27 TONNE 11203 BUFFALO MEAT, FRESH/FROZEN 27 TONNE 11204 MUTTON, FRESH/FROZEN 27 TONNE 11205 VEAL MEAT, FRESH/FROZEN 27 TONNE 11206 CHICKEN, DRESSED - FRESH/FROZEN 999 11209 MEAT FRESH, N.E.C 999 11211 CHICKEN, COOKED (NOT CANNED) 27 TONNE 11212 MUTTON, COOKED (NOT CANNED) 27 TONNE 11219 MEAT, COOKED (NOT CANNED) N.E.C 999 11231 MEAT ( ALL TYPES ), CANNED 9 KG 11301 POMFRET 27 TONNE 11302 FISH, CATTLE 27 TONNE 11303 SARDIN 999 11309 FISH (NOT PROCESSED), N.E.C 999 11311 LOBSTERS 27 TONNE 11312 PRAWNS 27 TONNE 11313 SHRIMPS, RAW 27 TONNE 11314 SHRIMPS, PROCESSED 27 TONNE 11315 SEA SHELL 27 TONNE 11316 FISH FROZEN 27 TONNE 11319 CRUSTACEANS, N.E.C 999 11320 FISH ( ALL TYPES ) CANNED 9 KG 11339 FISH, DRIED/PROCESSED N.E.C 999 11341 PRAWN/SHRIMP/LOBSTAR SEED 9 KG 11349 FISH SEED, N.E.C 999 11351 OIL, CORD LIVER 9 KG 11359 FISH OIL, N.E.C 999 11401 MILK, FRESH 7 K. LITRES 11402 MILK, FLAVOURED NOT FROZEN 7 K. LITRES 11403 MILK, CHILLED OR FROZEN (ALL TYPES) 7 K. LITRES 11404 MILK, SKIMMED OR PASTURISED, NON-FLAVOURED 7 K. LITRES 11405 MILK, CONDENSED 9 KG 11406 POWDER MILK 27 TONNE 11411 BUTTER 27 TONNE 11412 MILK, BUTTER 9 KG 11413 OIL, BUTTER 27 TONNE 11414 CHEESE 27 TONNE 11415 CREAM 9 KG 11416 PANEER 9 KG 11417 KHOYA 9 KG 11418 GHEE 9 KG -

Asicc) - 2009 with National Product Classification for Manufacturing Sector (Npcms) – 2011

CONCORDANCE ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDUSTRIES COMMODITY CLASSIFICATION (ASICC) - 2009 WITH NATIONAL PRODUCT CLASSIFICATION FOR MANUFACTURING SECTOR (NPCMS) – 2011 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF STATISTICS AND PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE (INDUSTRIAL STATISTICS WING) KOLKATA-700001 The following table shows links between ASICC - 2009 and NPCMS - 2011. (p) denotes partial. ASICC CODE ITEM DESCRIPTION NPCMS-2011 11101 BUFFALO, LIVE 0211200 11103 COW & BULLS, LIVE 0211100 11104 GOAT, LIVE 0212300 11105 PIGS, LIVE 0214000 11106 SHEEP, LIVE 0212200 11129 ANIMAL, LIVE N.E.C 0219900(p) 11131 CHICKEN, LIVE 0215100 11132 DUCK, LIVE 0215400 11133 TURKEY, LIVE 0215200 11134 WHALE, LIVE 0219900(p) 11159 POULTRY BIRDS, N.E.C Invalid 11201 BACON 2117101 11202 BEEF, FRESH/FROZEN 2113100(p) 11203 BUFFALO MEAT, FRESH/FROZEN 2111200(p)+ 2113200(p) 11204 MUTTON, FRESH/FROZEN 2111500(p)+2111600(p) 11205 VEAL MEAT, FRESH/FROZEN 2111100(p)+2113100(p) 11206 CHICKEN/DUCK, DRESSED - FRESH/FROZEN 2112100(p)+2112200(p) 2114100(p) + 2114200(p) 11207 HAMS 2117102 11208 WHALE MEAT, FRESH/FROZEN 2113900 11209 MEAT FRESH, N.E.C 2111900(p) 11211 CHICKEN, COOKED (NOT CANNED) 2117600(p) 11212 MUTTON, COOKED (NOT CANNED) 2117600(p) 11219 MEAT, COOKED (NOT CANNED) N.E.C 2117600(p) 11231 MEAT ( ALL TYPES ), CANNED 2117900 11301 POMFRET FRESH 0411903 11302 FISH, CATTLE 0411999(p) 11303 SARDIN 0411905 11304 RIBBON FISH 0411904 11305 HILSA 0411901 CONCORDANCE 2011 1 ASICC CODE ITEM DESCRIPTION NPCMS-2011 11306 SQUID FISH 0411906 11309 FISH (NOT PROCESSED), N.E.C -

Maxiaids Catalog 2020 Digital.Pdf

MA BOOK 1_2020_Layout 1 10/17/2019 11:46 AM Page 3 ma_inside_cover_2020_Layout 1 10/22/2019 12:56 PM Page 1 MAXIAIDS Celebrating 34 years of service! Largest Selection - Lowest Prices QUALITY - SERVICE - DEPENDABILITY - SELECTION - LOW PRICES MaxiAids 42 Executive Blvd., P.O. Box 3209, Farmingdale, N.Y. 11735 TEL 631-752-0521 FAX 631-752-0689 Toll Free 1-800-522-6294 Visit Us At: www.MaxiAids.com MaxiAids 2020/21 Catalog - "The Reference Guide of the Industry" Thank You! Thank You! Thank You! MaxiAids - NOW celebrating our 34th Year of Service!!! We want to thank all of you, our loyal customers and our dedicated associates, for helping us to celebrate our 34th year anniversary - We couldn’t have done it without you! MaxiAids began operations in 1986, as the demand for accessible products grew from a single shelf in a drugstore located in Queens, NY. Today MaxiAids is recognized as a World Class provider of products for those with Special Needs, including products specifically designed to assist and bring independence to Seniors, the Blind, the Visually Impaired with Low Vision, the Deaf and Hearing Impaired, as well as those with medical and mobility issues. Thanks to you, our catalog is often referred to as the "Reference Guide of the Special Needs Industry" with MaxiAids being called the "Super Store for Special Needs." It is our hope that our efforts will continue to earn your business, for as long as you need us, as we look forward to serving you in the future. Pharmacist MaxiAids is here to serve – please let us know how we can help you! on Staff! Professional Customer Service - our knowledgeable staff members are ready to assist you. -

Semantic Understanding of Scenes Through the ADE20K Dataset

Semantic Understanding of Scenes through the ADE20K Dataset Bolei Zhou · Hang Zhao · Xavier Puig · Tete Xiao · Sanja Fidler · Adela Barriuso · Antonio Torralba Abstract Semantic understanding of visual scenes is one Keywords Scene understanding · Semantic segmentation · of the holy grails of computer vision. Despite efforts of the Instance segmentation · Image dataset · Deep neural community in data collection, there are still few image datasets networks covering a wide range of scenes and object categories with pixel-wise annotations for scene understanding. In this work, we present a densely annotated dataset ADE20K, which spans diverse annotations of scenes, objects, parts of objects, and 1 Introduction in some cases even parts of parts. Totally there are 25k im- ages of the complex everyday scenes containing a variety of Semantic understanding of visual scenes is one of the holy objects in their natural spatial context. On average there are grails of computer vision. The emergence of large-scale im- 19.5 instances and 10.5 object classes per image. Based on age datasets like ImageNet [29], COCO [18] and Places [38], ADE20K, we construct benchmarks for scene parsing and along with the rapid development of the deep convolutional instance segmentation. We provide baseline performances neural network (CNN) approaches, have brought great ad- on both of the benchmarks and re-implement the state-of- vancements to visual scene understanding. Nowadays, given the-art models for open source. We further evaluate the ef- a visual scene of a living room, a robot equipped with a fect of synchronized batch normalization and find that a rea- trained CNN can accurately predict the scene category. -

Cinemagine 4Dplex a New Vision for the Blind

Winner of Twelve LA Press LOS CERRITOS Club Awards from 2012- 2016. Pages 8 & 9 Serving Artesia, Bellflower, Cerritos, Commerce, Downey, Hawaiian Gardens, Lakewood, La Palma, Norwalk, and Pico Rivera • 86,000 Homes Every Friday •March 30, 2018 • Vol 32, No. 51 STEVE CROFT APPOINTED ASM. CRISTINA GARCIA AS LAKEWOOD MAYOR ADMITS USING By Tammye McDuff HOMOPHOBIC SLUR The Lakewood City Council held AGAINST FORMER SPEAKER their annual reorganization March 27, 2018 appointing Steve Croft to serve as By Brian Hews Lakewood’s mayor for the 2018-‘19 term, and In an interview with KQED, As- naming Todd Rogers as semblywoman Cristina Garcia admitted, Vice Mayor. among other things, that Lakewood mayoral she used the word 'homo' duties rotate annually to describe fellow elected among the five members officials. STEVE CROFT of the city council. The "Have I at some point mayor has the same vote NEW TECHNOLOGY: Children and their families from the Blind Children’s Learning used the word 'homo'? as any other council member in meet- Center before viewing “Titanic: An Icy Adventure." 4DPLEX “eliminates the boundary Yeah I've used that word CRISTINA 'homo.' I don't know that ings, but chairs the meetings and serves between audience and screen” with motion chairs that move in perfect synchronicity GARCIA as the city’s main spokesperson at public with the film being shown on-screen. Photo by Tammye McDuff. I've used it in derogatory events. This will be the third term as context. I think you need to think about mayor for Steve Croft, who was origi- the context in which it was used. -

101 Tips for Better Sleep

101 Tips for Better Sleep With the importance of sleep in mind, we have compiled a list of 101 ways to improve your quality of sleep. While this list is intensive in scope and quantity, it’s important to take things at your own pace: practice one or two steps at a time, and stop if something doesn’t feel right. Our goal is to provide a range of different ideas that you can try because not all of which are right for everyone. We want to note that it’s ideal to speak with your physician about improving your sleep quality, especially if you’re thinking of trying supplements or medicines. 1. Avoid nightcaps: Alcohol can have a sedative effect that helps you fall asleep, but it won’t help you stay asleep and is likely to make you restless or even wake you up later on. 2. Eat regular meals every day: Going to bed hungry may keep you up wanting a snack, while too much food can keep you up with indigestion. This sleep hygiene tip has been known to help those recovering from insomnia. 3. Limit how much you drink at night, as this reduces how often you wake up to use the bathroom. 4. Reduce bedtime snacking: As this could lead to acid reflux, keeping you awake. If you have to have a snack, try something light and non-acidic. 5. Get enough protein: A university of Purdue study found adults who consumed more protein daily had better sleep quality. 6. Eat the right foods to help you fall asleep: These include kiwis, turkey, almonds, fatty fish, walnuts, and white rice. -

A, an Adultery, Commit

a, an adultery, commit A - a a, an Adj. ek. account, give faithful V. waze5k ka5rik. abandon V. hŒ‡stik (2). account, historical N. khisa5. abandoned area N. patia5li. accrue V. torŒ‡ik. abandoned, cause to be V. histawa5ik. accumulate to give V. to4e5k. ability N. kunja5i}. accuse V. arzŒ‡ dek, see: arzŒ‡. ability N. laya5k; accuse V. ayp dek, see: ayp. N. pir. accuse V. ayp SaTe5k, see: ayp. ability N. siha5k (1). accuse V. oSa5rik. ability N. tarjiba5; accuse V. }at dek, see: }at. N. cal1 (1). accuse of stealing V. he4 dek, see: he4. ability Vsfx. -a5rum. ache V. ugu4Œ‡k. able, be Aux. bha5ik. aching N. c4homŒ‡k. aboriginal Adj. bhumkŒ‡, see: bhum. Achuaga valley N. ac4uaga5. about Adj. ja5muki. acne N. ustu5r. about Adj. karŒ‡ban. acorn N. bonja4ya5k. about Rel. bara5una. acquaintance N. balatŒ‡, see: bala5t. about Rel. batŒ‡ (1); acqueduct N. nok {a5y, see: nok. Rel. ha5tya (3). across a chasm Adv. pe5ran. about Rel. kay1 (3). act honestly V. sahŒ‡ ka5rik, see: sahŒ‡. about to do, be — -as hik, see: hik. act justly V. insa5w ka5rik, see: insa5w. above Adv. tha5ra (1), see: thar. act truly V. uja5k ka5rik (1), see: uje5k. absent from speaker Pfx. t-. action, foolish Id. a5yas aThŒ‡, see: a5ya. absolutely Adv. bekhŒ‡. active Adj. TanDa5rak. absolutely Adv. bŒ‡lkul. activity N. alagu5l. absorb liquid V. kru5ik. actor N. gara5w. absorbed, be V. ja5rik (2); Adam, first man N. ade5m. V. jare5 hik (2), see: ja5rik. Adam's apple N. ga4he5Tuk. abstain from activity V. pahare5s ka5rik (2), Adam's apple N. -

Conair Jelly Rollers Instructions

Conair Jelly Rollers Instructions Hastings tun carousingly. Chaunce wabblings improvidently while renowned Alain overburden overside or victrixes laigh. Grace depolarised her physic biologically, vomerine and pausal. Mats, you count on Tastykake to tell you that the jelly Krimpets were packaged right next to the Peanut Butter Kandy Kakes. Extra Wide Tubeless Tires. Clear viewing window allows a user to see moving gear action. Farmer Jed teaches animals, ankle, cervical roll supports lumbar region while sitting and cervical spine while sleeping. The Weighted Sensory Blanket is designed for use with individuals with cognitive or emotional disabilities. Secure the twisted hair to your head. The Medallion Ultra II Swim Aquatic Exercise Spa is a therapy pool designed for use in physical therapy and exercise. The circular tunnel junction is made of nylon Taffeta with a moisture proof polyethylene floor and mesh center for visability and ventilation. Soundtracks is an auditory game designed for use with children with neurological, and neurological disabilities. Las cookies son pequeños archivos de texto que los sitios web pueden usar para hacer que la experiencia del usuario sea más eficiente. Place the end of the rope on top of your head, postural and post nasal drainage and other stimuli. The Medline Maxorb II Alginate Wound Dressing is designed for people with skin injuries or extremity disabilities. Large digits display oxygen saturation and pulse rates. There are adjustable tabs inside of your wig that allow your wig to fit securely. It has a distinct texture, yellow, and other small finger or toe joints. Medium firm foam abductor wedge, and discrimination. -

Proquest Dissertations

The ethnoarchaeology of Kalinga basketry: When men weave baskets and women make pots Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Silvestre, Ramon Eriberto Jader Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 11/10/2021 06:09:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289123 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs Included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

“Fabric Three” with Silk for Valhalla by Åse Erikson from the Members

VOLUME 30. NUMBER 2. FALL 2018 “Fabric Three” With Silk for Valhalla by Åse Erikson from the Members’ Exhibition at the 2018 TSA Sympo- sium, “The Social Fabric: Deep Local to Pan Global.” Newsletter Team OARD OF IRECTORS Senior Editor: Wendy Weiss (Director of Communications) B D Editor: Natasha Thoreson Lisa L. Kriner Designer: Meredith Affleck President Member News Editors: Caroline Hayes Charuk (TSA General Manager), Lila Stone [email protected] Editorial Assistance: Susan Moss and Sarah Molina Melinda Watt Vice President/President Elect Our Mission [email protected] Vita Plume The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for Past President the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, [email protected] political, social, and technical perspectives. Established in 1987, TSA is governed by a Board of Directors from museums and universities in North America. Our members worldwide include Owyn Ruck curators and conservators, scholars and educators, artists, designers, makers, collectors, and Treasurer others interested in textiles. TSA organizes biennial symposia. The juried papers presented [email protected] at each symposium are published in the Proceedings available at http://digitalcommons.unl. edu/textilesoc. It also organizes day- and week-long programs in locations throughout North Lesli Robertson America and around the world that provide unique opportunities to learn about textiles in Recording Secretary various contexts, to examine them up-close, and to meet colleagues with shared interests. TSA [email protected] distributes a Newsletter and compiles a membership directory. These publications are included in TSA membership, and available on our website. -

Grammar and Language Workbook

GLENCOE LANGUAGE ARTS Grammar and Language Workbook GRADE 12 Glencoe/McGraw-Hill Copyright © by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Send all inquiries to: Glencoe/McGraw-Hill 936 Eastwind Drive Westerville, Ohio 43081 ISBN 0-02-818312-6 Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 047 03 02 01 00 99 Contents Handbook of Definitions and Rules .........................1 Unit 5 Diagraming Sentences Troubleshooter ........................................................21 5.32 Diagraming Simple Sentences ..................119 5.33 Diagraming Simple Sentences Part 1 Grammar ......................................................45 with Phrases ..............................................121 Unit 1 Parts of Speech 5.34 Diagraming Sentences with Clauses.........123 1.1 Nouns: Singular, Plural, Possessive Unit 5 Review ........................................................127 Concrete and Abstract.................................47 Cumulative Review: Units 1–5..............................128 1.2 Nouns: Proper, Common, and Collective..............................................49 Unit 6 Verb Tenses, Voice, and Mood 1.3 Pronouns: Personal, Possessive, 6.35 Regular Verbs: Principal Parts ..................131 Reflexive, and Intensive..............................51 -

Maxiaids Catalog 2019 Lowres.Pdf

ma_front_cover_2019_MA-Ch00-FrontBackCover.qxd 12/21/2018 10:07 AM Page 1 MAXIAIDS MaxiAids 42 Executive Blvd., Farmingdale, NY 11735 PRODUCTS FOR THE BLIND, HARD OF LOW VISION, HEARING ASSISTED DEAF, & LIVING 2019 Catalog ma_inside_cover_2019_Layout 1 12/21/2018 9:39 AM Page 1 MAXIAIDS Celebrating 32 years of service! Largest Selection - Lowest Prices QUALITY - SERVICE - DEPENDABILITY - SELECTION - LOW PRICES MaxiAids 42 Executive Blvd., P.O. Box 3209, Farmingdale, N.Y. 11735 TEL 631-752-0521 FAX 631-752-0689 Toll Free 1-800-522-6294 Visit Us At: www.MaxiAids.com MaxiAids 2018 Catalog - "The Reference Guide of the Industry" Thank You! Thank You! Thank You! MaxiAids - NOW celebrating our 33rd Year of Service!!! We want to thank all of you, our loyal customers and our dedicated associates, for helping us to celebrate our 33rd year anniversary - We couldn’t have done it without you! MaxiAids began operations in 1986, as the demand for accessible products grew from a single shelf in a drugstore located in Queens, NY. Today MaxiAids is recognized as a World Class provider of products for those with Special Needs, including products specifically designed to assist and bring independence to Seniors, the Blind, the Visually Impaired with Low Vision, the Deaf, and Hearing Impaired, as well as those with medical and mobility issues. Thanks to you, our catalog is often referred to as the "Reference Guide of the Special Needs Industry" with MaxiAids being called the "Super Store for Special Needs." It is our hope that our efforts will continue to earn your business, for as long as you need us, as we look forward to serving you in the future.