Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages McDermid, R. T. W. How to cite: McDermid, R. T. W. (1980) The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7616/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk II BEVERIEY MINSTER FROM THE SOUTH Three main phases of building are visible: from the East End up to, and including, the main transepts, thirteenth century (commenced c.1230); the nave, fourteenth century (commenced 1308); the West Front, first half of the fifteenth century. The whole was thus complete by 1450. iPBE CONSTIOOTION AED THE CLERGY OP BEVERLEY MINSTER IN THE MIDDLE AGES. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubHshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

The Will of John Morton

Running headARTICLES RIGHT The Will of John Morton – an introduction In the late spring of 2016, Dr Betty Knott, a retired Latinist from Glasgow University, graciously agreed to participate in The Missing Princes Project and offer her expertise. As the information gathering for the modern investigation into the disappearance of the sons of King Edward IV continued apace, it was becoming increasingly clear that the enquiry had to consider all potential sources of information. With John Morton’s role in the key period of investigation (1483–6), coupled with Dr Knott’s academic neutrality, revealing Morton’s will in full in English for the first time would not only be consistent with the aims and ambition of the project, but might offer new connections and insight into this important figure. Previously, only an epitome of Morton’s will was available in English translation.* With thanks to Marie Barnfield whose meticulous and informed transcript and decipherment of the very difficult hand of the original manuscript considerably expedited Dr Knott’s own reading of the original text, and author Isolde Martyn, whose investigations into John Morton instigated this complete English translation of his will. Philippa Langley MBE * C. Everleigh Woodruff, Kent Archaeological Society, 1914, vol 3, Sede Vacante Wills: Canterbury, pp 91–3. Complete Latin text pp 95–91. THE WILL OF JOHN MORTON, archbishop of Canterbury, c. 1420–1500 BETTY I. KNOTT This article, on behalf of The Missing Princes Project, is based on the original Latin text of the will of John Morton (c. 1420–1500), archbishop of Canterbury 1486–1500, and cardinal (1496). -

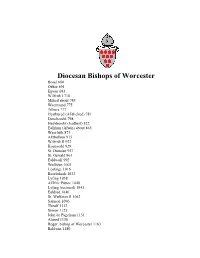

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title -

Sanctuary Seekers in England, 1380-1557 (Ordered by Date)

(London: G. Sanctuary Seekers in England, 1380-1557 (ordered by date) Shannon McSheffrey Professor of History, Concordia University The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Mediaeval England © Shannon McSheffrey, 2017 archive.org Illustration by Ralph Hedley from J. Charles Cox, Allen and Sons, 1911), p. 108. 30/05/17 Sanctuary Seekers in England, c. 1380-1550, in Date Order Below are presented, in tabular form, all the instances of sanctuary-seeking in deal of evidence except for the name (e.g. ID #1262). In order to place those England that I have uncovered for the period 1380-1557, more than 1800 seekers seekers chronologically over the century and a half I was considering, in the altogether. It is a companion to my book, Seeking Sanctuary: Crime, Mercy, and absence of exact dates I sometimes assigned a reasonable year to a seeker (always Politics in English Courts, 1400-1550 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). As I noted in the summary section). As definitions of specific felonies were somewhat have continued to add to the data since that book went to press, the charts here elastic in this era, I have not sought to distinguish between different kinds of may be slightly different from those in the book. asportation offences (theft, robbery, burglary), and have noted in the summary different forms of homicide only as they were indicated in the indictment. Details Seeking Sanctuary explores a curious aspect of premodern English law: the right of on the offences are noted in the summaries of the cases; there is repetition in the felons to shelter in a church or ecclesiastical precinct, remaining safe from arrest cases where several perpetrators were named in a single document so that and trial in the king's courts. -

Sewanee News, 1985

GyzVT* ft * March 1985 ^^ -mm v Dean Booty Resigns The Very Rev. John E. Booty, dean and pastor to his students." He said of the School of Theology, has re- that the heavy load of administra- signed and plans to leave the dean's tive duties takes its toll on all semi- office sometime after the end of the nary deans, a condition he said he academic year. intends to change at Sewanee. Dean Booty submitted his letter Dean Booty assumed his duties at of resignation to Vice-Chancellor Sewanee in 1982. Previously he had Ayres on February 25 and then an- been professor of church history at nounced his decision to his faculty the Episcopal Divinity School in and students. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had In his letter of resignation. Dean taught at Virginia Theological Sem- Booty said: "That I can no longer inary. His service to the Church has function effectively here does not been rich and varied. He has also negate my conviction that the written numerous books on church School of Theology has a fine future history, prayer, and spiritual life. ahead of it and presently does a While at Sewanee, Dean Booty more than good job of preparing has overseen the move of the School priests for the Episcopal Church," of Theology from St. Luke's Hall to Vice-Chancellor Ayres said he re- more modern facilities of Hamilton gretted very much Dean Booty's Hall and has been instrumental in resignation, citing the dean's "won- the increase of enrollment from derful gifts as a scholar, teacher, about sixty to eighty-two students. -

"The Alert Index" PDF Format

1 EISKE, Albert Julius 11/09/1931 ANTCLIFFE, Jane 01/09/1933 ADAIR, Bessie 21/09/1934 APPEL, John George 22/03/1929 ADAIR, John Hamilton 17/08/1934 ARMITAGE, E. 26/10/1934 ADAIR, Mrs. Elise M. 15/02/1929 ARNDT, Fredericka Louisa 26/07/1935 ADAM, Charles Henry 23/11/1934 ARNOLD, George 17/07/1931 ADAM, Sam 30/03/1934 ARTHUR, Margaret Jean 16/06/1933 ADAM, W. P. 12/08/1932 ASHTON, Mrs. Wm. 28/11/1930 ADAMS, Fredica 07/09/1928 ASHTON, Sarah 13/09/1935 ADAMS, Thomas 27/11/1931 ASHTON, William 26/02/1932 ADAMSON, Caroline 01/07/1932 ASMUS, Isabella 03/01/1936 ADAMSON, F. 23/08/1935 ATKINS, Jane Elizabeth 04/09/1931 ADDISON, Albert 21/03/1930 ATKINSON, Richard 13/06/1930 ADIE, George 22/01/1937 AUSTIN, W. H. 01/06/1934 AHLBRAND, Herman Gustave 21/12/1934 AXELSEN, Nils 05/05/1933 AIRD, Thomas Henry 06/11/1931 AYRE, Norman Arthur 11/08/1933 AIRTON, Elizabeth Ann 06/05/1932 BACK, Frederick 01/03/1935 AISTHORPE, Thomas 06/07/1934 BAIN, Jane Keer 24/08/1934 AITCHISON, John 22/02/1929 BAKER, George 05/08/1932 AITKEN D. 22/11/1935 BALKIN, James 06/03/1931 AITKEN, Elizabeth Mary 14/10/1932 BALLS, Sarah 17/06/1932 AITKEN, Jack 19/03/1937 BANDHOLZ, Henrich 02/12/1932 ALEXANDER, William 23/07/1937 BANKHEAD, Elizabeth Helena 03/07/1936 ALLAN. Andrew 25/09/1936 BANVILL, Emma 02/07/1937 ALLEN, Esther Emily 04/12/1931 BARBELER, Annie 02/02/1934 ALLEN, Mr. -

English Translation of Dr Morton’S Will

1 Translated from the Latin by Dr Betty Knott (University of Glasgow, ret) on behalf of The Missing Princes Project - published 1 June 2018 The Following Work Represents the First Complete English Translation of Dr Morton’s Will Will of John Morton, Cardinal, Archbishop of Canterbury (c.1420 – 15 September 1500) Made 16th July 1500 Proved 22nd October 1500 In the Name of God, Amen I, John Morton, by the mercy of God, Cardinal priest of the titular church of St Anastasia in the most holy church of Rome, Archbishop of Canterbury, Primate of all England and Legate of the Apostolic See, being well in body, praise be to God, and of sound mind, being put in remembrance that for all men death is inevitable and that there is nothing more certain than death, even if the hour and mode of death are uncertain – and nothing can be more horrible than giving no thought to God and one's own death, seeing that the sinner, who during his life gave no thought to God, on his deathbed often has no consciousness of self – desiring therefore, while my body still has health and strength, to dispose of the resources and goods, which our Redeemer of his goodness has deigned to bestow abundantly upon me in this vale of tears, in a manner pleasing to him and for the discharging of my conscience, I make my testament as follows: 8 First, I revoke and annul all wills and testaments in any way concerning my goods and chattels previously made by me, and further I wish and by these presents declare that all wills and all testaments of this sort on my part, in so far as and to the extent that they are contrary to this my testament, shall without contradiction be of no force or effect, and that this my testament, subscribed in my own hand, shall be and be considered and observed as my true, complete and last will and as my true, complete and only legitimate testament. -

An Edition of the Cartulary of St. Mary's Collegiate Church, Warwick

An Edition of the Cartulary of St. Mary's Collegiate Church, Warwick Volume 1 of 2 Charles Richard Fonge submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ,. University of York Department of History October 1999 Abstract This thesis is an edition of the fifteenth-century cartulary of the collegiate church of St. Mary and All Saints, Warwick (founded c. 1123). The cartulary, whose documents span the period 1100-1500, has been edited in full. Each document has been dated, is preceded by a summary in English, and followed by notes on the text. These include references to originals, other manuscript and printed copies, variant readings from contemporary copies, and furnish reasons for assigning a particular date, besides biographical and contextual information relating to the document and those mentioned within it. A full introduction to the cartulary and editorial method is given at the beginning of the edition itself. Appended to the edition is also a biographical index of the college's fasti and an edited version of an important set of its 1441 statutes. A more contextual introduction to this edition consists of five chapters, which explore the college's history and development and form the initial volume. The first chapter deals with the foundation of church and college and the importance of their Anglo-Saxon past, in which context Norman contributions must be viewed. Chapter 2 defines le constitution of the college and explores the interplay between individual and community, personality and politics, in shaping its legislation, constitution and the practice of each. Chapter 3 examines the place of the collegiate church as an institution in the diocesan and politico-economic frameworks of the later Middle Ages, before assessing relations between St. -

Open a PDF List of This Collection

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 MISCELLANEOUS DEEDS CLC/522 Reference Description Dates CLC/522/001 Deeds relating to property on Monkwell 1642 - 1748 [Mugwell] Street The earlier documents refer to Windsor House. Later documents refer to Windsor Court. Included in the bundle are a copy of Fire Court decisions regarding the property, dated 1668, which lists the pre-Fire tenants and their rents. The 1717, 1719, 1739 deeds mention the rebuilding of the site after the Great Fire. The 1717 deed mentions a "Meeting House" being part of the property and in 1748 Windsor Court included "A Publick Place of Worship for Protestant Dissentors" . 1 bundle of 15 items CLC/522/002 Deed of gift of messuages in St Leonards, 1468 Nov 20 Shoreditch and relating to lands and tenements in St Botolph outside Bishopsgate, City of London Described as lying between the land of William Heryot to the north and east, land recently of William Heryot to the south, and the King's highway to the west. Conveyed by John Marny, John Say, William Tyrell de Beches, Robert Darcy, Thomas Cook, knight, John Clopton esq, John Grene, John Poynes esq, Henry Skeet, chaplain, Robert Hotoft, and Richard Chercheman, to John Gadde, sherman, John Marchall, mercer, William Heryot, sherman, and John Weldon, grocer, all of London 1 document CLC/522/003 Abstract of title to leasehold premises situtate in 1804 Liquorpond Street and Leicester Street in the Parish of Saint Andrew Holborn in the County of Middlesex Provides a summary of ownership between 1694 and 1804. In 1694 William Ward bequeathed 5 houses and various leases to his son Alexander Ward, his daughter Elizabeth Cock and her son William Cock. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

Richard III, the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, and Two Turbulent Priests ANNE F. SUTTON and LIVIA VISSER-FUCHS In June and July 1483 the two universities of England wrote to Richard as the duke of Gloucester and as king and asked for his benevolent mercy towards two of their graduates: Thomas Rotherham of Cambridge and John Morton of Oxford.One of the letters is in hasty and informal English and the other in competent, formal Latin, embellished with a few classical quotations. The one reads as a spontaneous, warm and anxious plea, the other as a careful exercise in rhetoric. Their dramatic difference in tone and formprovides an interesting contrast as exercises in the art of petitioning. Why were the letters so different? The two men were of an age, born in the 14205 and dying in 1500. They both came fromsimilar backgrounds and had to make their own way in the world. They both had university educations, but whereas Rothcrham aimed at a doctorate in theology, Morton graduated in the two laws, 3 significant difference. Rotherham became a notable benefactor in his lifetime and is acknowledged as such by his biographers. Morton founded no institutions, although he did contribute to building projects, and his biographers choose to emphasise his brilliance and value as a royal servant. Both were accomplished administrators. Rotherham held the office of chancellor of England competently as a man of the church, while Morton held the same office as the king’s prime minister in every sense, and gained great personal unpopulatity. Perhaps it can be said Rotherham was in the last analysis a clergyman, while Morton was above all a consummate politician and lawyer. -

PAVER's Marriage Licences

'^^ /J&' J 3 1404 00553 4463 ''1 , \ ' » O r^^ f^:^J qIVO^ Ms^ p.\^- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University-Idaho http://www.archive.org/details/paversmarriageliOOchur THE FOUNDED 1863. INCORPORATED 1893. Record Series. VOL. XL. FOR THE YEAR 1908. PAVER'S Marriage Licences. EDITED BY JOHN WM. CLAY, F.S.A., Vice-President of the Yorkshire Archaological Society PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY. 1909. INTRODUCTION. PAVER'S Marriage Licences were begun to be printed by the Yorkshire Archccological Society in Volume VII. of their Journal. They were continued in Volumes IX., X., XL, XII., XIIL, XIV., XVI., XVIL, XX. The Council of the Society having considered that in that form the work would take many years to be finished, decided to transfer it to the ^' Record Series." The present volume takes it up where it was left off in the Journal, viz., from the year 1630, and continues it till the year 1644. Another volume will perhaps complete the work to 17 14, which is the end of the MS. in London. A full account of Paver's MSS. was given in the Journal, Vol. XX., p. 68, but it may be again stated that these licences, which were originally at York, were transcribed by William Paver, the Genealogist, in two volumes, which are at the British Museum, Add. MSS. 29667-8. The original MSS. at York are not believed to be in existence, at least the earlier parts. The entries have been transcribed by Miss Osier, a copyist at the British Museum, and the editor has himself examined most of the proofs with the MSS., so it is hoped that the work is as perfect as possible, though sometimes difficulties have arisen owing to the contractions used by Paver, and to his frequent queries as to the spelling of the names.