Research Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Netflix's Big Mouth

Netflix’s Big Mouth Big Mouth = Big Topics The first season of Netflix’s new animated show Big Mouth debuted on September 29, 2017 and is very popular among teens and young adults. Boasting an all-star cast and a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, the cartoon is about middle schoolers going through puberty in the most explicit, perverse, and, at times, depraved way possible. Puberty is indeed a difficult time for all of us, and while the show does bring some good to the discussion, it’s also fraught with problems. What do I need to know about Big Mouth? It’s an adult cartoon based on the real-life experiences that comic writers Nick Kroll and An- drew Goldberg had as kids growing up in New York. They share, in graphic detail, what it was like growing up and going through puberty. As most young men do, Nick and Andrew strug- gled through lust, sexuality, relationships with girls, and the ups and downs of friendship. The show features some of the most popular comedians of our time as the voices, including: John Mulaney, Fred Armisen, Kristen Wiig, and Jordan Peele. Although the show is about pre-teens, it is intended for an adult audience. However, Netflix does not effectively limit younger viewers’ access, and undoubtedly, there will be many teens and pre-teens who watch the show. Many of them have lots of questions about sex, and they will be drawn to the show in hopes of finding answers. Unfortunately, due to the content, they are likely to develop some severely warped ideas from watching it. -

Film Financing

2017 An Outsider’s Glimpse into Filmmaking AN EXPLORATION ON RECENT OREGON FILM & TV PROJECTS BY THEO FRIEDMAN ! ! Page | !1 Contents Tracktown (2016) .......................................................................................................................6 The Benefits of Gusbandry (2016- ) .........................................................................................8 Portlandia (2011- ) .....................................................................................................................9 The Haunting of Sunshine Girl (2010- ) ...................................................................................10 Green Room (2015) & I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore (2017) ...........................11 Network & Experience ............................................................................................................12 Financing .................................................................................................................................12 Filming ....................................................................................................................................13 Distribution ...............................................................................................................................13 In Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................13 Financing Terms .....................................................................................................................15 -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

Politics of Parody

Bryant University Bryant Digital Repository English and Cultural Studies Faculty English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles Publications and Research Winter 2012 Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Bryant University Ethan Thompson Texas A & M University - Corpus Christi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Day, Amber and Thompson, Ethan, "Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody" (2012). English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles. Paper 44. https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Research at Bryant Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bryant Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Live from New York, It’s the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Assistant Professor English and Cultural Studies Bryant University 401-952-3933 [email protected] Ethan Thompson Associate Professor Department of Communication Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi 361-876-5200 [email protected] 2 Abstract Though Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” has become one of the most iconic of fake news programs, it is remarkably unfocused on either satiric critique or parody of particular news conventions. -

At the Mission San Juan Capistrano

AT THE MISSION SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO by José Cruz González based on the comic strip “Peanuts” by Charles M. Schulz directed by Christopher Acebo book, music and lyrics by Clark Gesner additional dialogue by Michael Mayer additional music and lyrics by Andrew Lippa directed and choreographed by Kari Hayter OUTSIDE SCR 2021 • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • 1 THE THEATRE Tony Award-winning South Coast Repertory, founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson, is led by Artistic Director David Ivers and SPRING/SUMMER 2021 SEASON Managing Director Paula Tomei. SCR is recog- nized as one of the leading professional theatres IN THIS ISSUE Get to know, or get reacquainted with, South Coast Repertory in the United States. It is committed to theatre through the stories featured in this magazine. You’ll find information about both that illuminates the compelling personal and Outside SCR productions: American Mariachi and You’re a Good Man, Charlie social issues of our time, not only on its stages but Brown, as well as the Mission San Juan Capistrano, acting classes for all ages and a through its wide array of education and engage- host of other useful information. ment programs. 6 Letter From the Artistic Director While its productions represent a balance of clas- That Essential Ingredient of the Theatre: YOU sic and modern theatre, SCR is renowned for The Lab@SCR, its extensive new-play development program, which includes one of the nation’s larg- 7 Letter From the Managing Director est commissioning programs for emerging, mid- A Heartfelt Embrace career and established writers and composers. -

Depaul Animation Zine #1

Conditioner // Shane Beam D i e F l u c h t / / C a r t e r B o y c e 2 0 1 6 S t u d e n t A c a d e m y A w a r d B r o n z e M e d a l 243 South Wabash Avenue Chicago, IL 60604 #1 zine a z i n e e x p l o r i n g t h e A n i m a t i o n C u l t u r e a t D e P a u l U n i v e r s i t y in Chicago R a n k e d t h e # 1 0 A n i m a t i o n M F A P r o g r a m a n d # 1 4 A n i m a t i o n P r o g r a m i n t h e U . S . b y A n i m a t i o n C a r e e r R e v i e w i n 2 0 1 8 D e P a u l h a s 1 3 f u l l - t i m e A n i m a t i o n p r o f e s s o r s , o n e o f t h e l a r g e s t f u l l - t i m e A n i m a t i o n f a c u l t i e s i n t h e U S , w i t h e x p e r t i s e i n t r a d i t i o n a l c h a r a c t e r a n i m a t i o n , 3 D , s t o r y b o a r d i n g , g a m e a r t , s t o p m o t i o n , c h r a c t e r d e s i g n , e x p e r i m e n t a l , a n d m o t i o n g r a p h i c s . -

PAUL LIBERTI - Voice Actor/Muppet Performer/ VO Educator - Bio

PAUL LIBERTI - Voice Actor/Muppet Performer/ VO Educator - Bio Paul Liberti had his first professional puppet work with Jim & Jane Henson in 1984 and has worked for Sesame Workshop, Sesame Street, Nickelodeon, Noggin, PBS, MTV, VH1, Muppet Babies Live, Muppet Show On Tour, and more. His students have gone on to work on Nickelodeon, Disney, Noggin, PBS, Avenue Q, and Sesame Street and more! Paul also trained many of the Avenue Q puppeteers in Puppet ‘Boot Camp’. He toured with the Muppet Show On Tour - Directed by Jon Stone and Jim Henson and the Muppet Babies Live! And worked on the film - MUPPETS TAKE MANHATTAN. As an Actor and Improv Performer - Second City, The Funny Firm (Chicago) - Chicago City Limits (NYC). Films - The Stepford Wives w/ Nicole Kidman, Dummy w/ Adrian Brody, No Such Thing w/Helen Mirren, Lead in Showtime’s - Priority Seating Directed by Meg Busch - TV - Comedy Central's The Daily Show, UnAuthorized Biography. Internet - Mike Stickle’s - Floaters. In Voice Over, he currently teaches competitive classes in Los Angeles and NYC and Nationally for SAG/AFTRA Foundation in independently in Commercial VO, Audio Book Narration, Video Game Character work and Animation and TV Puppeteering. He also teaches Accents for Actors - for Animation, Voice Actors, Film Actors, and also actors on Broadway and London's West End Theater, Regional Theater with recent shows like Disney's Frozen, Avenue Q, Disney’s Live Tangled, and on TV - USA Network - Falling Water, The National Theater's - One Night in Miami, Greater Tuna, Anastasia, My Fair Lady, Brigadoon among others. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

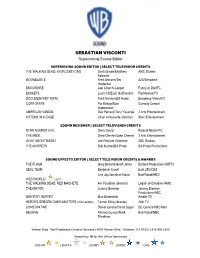

SEBASTIAN VISCONTI Supervising Sound Editor

SEBASTIAN VISCONTI Supervising Sound Editor SUPERVISING SOUND EDITOR | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS THE WALKING DEAD: WORLD BEYOND Scott Gimple/Matthew AMC Studios Negrette MOONBASE 8 Fred Armisen/Tim A24/Showtime Heidecker BROCKMIRE Joel Church-Cooper Funny or Die/IFC BASKETS Louis CK/Zach Galifianakis Pig Newton/FX DOCUMENTARY NOW! Fred Armisen/Bill Hader Broadway Video/IFC CORPORATE Pat Bishop/Matt Comedy Central Ingebretson AMERICAN VANDAL Dan Perrault/Tony Yacenda 3 Arts Entertainment KITTENS IN A CAGE Jillian Armenante (director) Stoic Entertainment SOUND DESIGNER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS STAN AGAINST EVIL Dana Gould Radical Media/IFC THE MICK Dave Chernin/John Chernin 3 Arts Entertainment WHAT ABOUT BARB? Joe Port/Joe Wiseman ABC Studios THE MUPPETS Bob Kushell/Bill Prady Bill Prady Productions SOUND EFFECTS EDITOR | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS THE FLASH Greg Berlanti/Geoff Johns Berlanti Productions/WBTV SEAL TEAM Benjamin Cavell East 25C/CBS Lisa Joy/Jonathan Nolan Bad Robot/HBO WESTWORLD (2017) THE WALKING DEAD: RED MACHETE Avi Youabian (director) Legion of Creatives/AMC THE MAYOR Jeremy Bronson Jeremy Bronson Productions/ABC MINORITY REPORT Max Borenstein Amblin TV HEROES REBORN: DARK MATTERS (mini-series) Tanner Kling (director) 20th TV CONSTANTINE Daniel Cerone/David Goyer DC Comics/HBO Max BELIEVE Alfonso Cuaron/Mark Bab Robot/NBC Friedman Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.5305 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS . -

Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Major Papers Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers June 2018 Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style Dustin Jones University of Windsor, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Dustin, "Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style" (2018). Major Papers. 43. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/43 This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style By Dustin Jones A Major Research Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2018 © 2018 Dustin Jones Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style By Dustin Jones APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ N. Atkin Department of History ______________________________________________ M. Wright, Advisor Department of History May 17th, 2018 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this thesis and that no part of this thesis has been published or submitted for publication.