Sociology of Northeast India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Abikal Borah 2015

Copyright By Abikal Borah 2015 The Report committee for Abikal Borah certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) Supervisor: ________________________________________ Mark Metzler ________________________________________ James M. Vaughn A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M. Phil Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2015 A Region in a Mobile World: Integration of Southeastern sub-Himalayan Region into the Global Capitalist Economy (1820-1900) By Abikal Borah, M.A. University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Mark Metzler Abstract: This essay considers the history of two commodities, tea in Georgian England and opium in imperial China, with the objective of explaining the connected histories in the Eurasian landmass. It suggests that an exploration of connected histories in the Eurasian landmass can adequately explain the process of integration of southeastern sub-Himalayan region into the global capitalist economy. In doing so, it also brings the historiography of so called “South Asia” and “East Asia” into a dialogue and opens a way to interrogate the narrow historiographical visions produced from area studies lenses. Furthermore, the essay revisits a debate in South Asian historiography that was primarily intended to reject Immanuel Wallerstein’s world system theory. While explaining the historical differences of southeastern sub-Himalayan region with peninsular India, Bengal, and northern India, this essay problematizes the South Asianists’ critiques of Wallerstein’s conceptual model. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

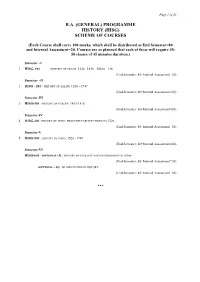

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

The TAI AHOM Movement in Northeast India: a Study of All Assam TAI AHOM Student Union

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 7, Ver. 10 (July. 2018) PP 45-50 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The TAI AHOM Movement in Northeast India: A Study of All Assam TAI AHOM Student Union Bornali Hati Boruah Research Scholar Dept. of Political science Assam University, Diphu campus, India Corresponding Author: Bornali Hati Boruah Abstract: The Ahoms, one of the foremost ethnic communities in the North East India are a branch of the Tai or Shan people. The Tai Ahoms entered the Brahmaputra valley from the east in the early part of the thirteenth century and their arrival heralded a new age for the people of the region. The ethnic group Tai Ahoms of Assam has been asserting their ethnic identity more than a century old today. The Ahoms who once ruled over Assam seek to maintain their distinct identity within the larger Assamese society. The Tai Ahoms of Assam faced a lot of problem after independence in different aspects. Moreover, though once Tai Ahoms ancestors were ruling race but today they have been squarely backward .They have been recognized as one of the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. As a measure to solve their multifold and multifaceted demands, the ethnic group Tai Ahoms has been struggling through their organizations. In present time, All Tai Ahom Student Union (ATASU) has been very much concerned about the various problems of Tai Ahoms community. While struggling for the overall development of the Tai Ahom community, rightly or wrongly the All Tai Ahom Student Union has been raising political issues and thus got involved in the politics of the state despite being a non-political organization. -

Women Education in Colonial Assam As Reflected in Contemporary Archival and Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal

SSRG International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 8 Issue 3, 80-86, May-June, 2021 ISSN: 2394 – 2703 /doi:10.14445/23942703/IJHSS-V8I3P112 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Women Education in Colonial Assam as Reflected In Contemporary Archival And Literary Records Chiranjib Dahal Assistant Professor, Department of History, J.D.S.G. College, Bokakhat Dist.: Golaghat, State: Assam, Country: India 785612 Received Date: 15 May 2021 Revised Date: 21 June 2021 Accepted Date: 03 July 2021 Abstract - The present paper makes an attempt to trace the which can be inferred from literacy rate from 0.2 % in genesis and development of women’s education in colonial 1882 to 6% only in 1947(Kochhar,2009:225). It reveals Assam and its contribution to their changing status and that for centuries higher education for women has been aspirations. The contribution of the native elites in the neglected and the report University Education Commission process of the development of women education; and 1948 exposed that they were against women education. In social perception towards women education as reflected in their recommendation they wrote “women’s present the contemporary periodicals are some other areas of this education is entirely irrelevant to the life they have to lead. study. Educational development in Assam during the It is not only a waste but often a definite disability” colonial rule has generally been viewed by educational (University Education Commission Report, Government of historians to be the work of British rulers who introduced India, 1948-49). Educational development in Assam a system of education with the hidden agenda of initiating during the colonial rule has generally been viewed by a process of socialization. -

International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI

SJIF Impact Factor: 6.047 Volume: 6 | November - October 2019 -2020 ISSN(Print ): 2250 – 2017 International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI : https://doi.org/10.36713/epra0003 IDENTITY MOVEMENTS AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN ASSAM Ananda Chandra Ghosh Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Cachar College, Silchar,788001,Assam, India ABSTRACT Assam, the most populous state of North East India has been experiencing the problem of internal displacement since independence. The environmental factors like the great earth quake of 1950 displaced many people in the state. Flood and river bank erosion too have caused displacement of many people in Assam every year. But the displacement which has drawn the attention of the social scientists is the internal displacement caused by conflicts and identity movements. The Official Language Movement of 1960 , Language movement of 1972 and the Assam movement(1979-1985) were the main identity movements which generated large scale violence conflicts and internal displacement in post colonial Assam .These identity movements and their consequence internal displacement can not be understood in isolation from the ethno –linguistic composition, colonial policy of administration, complex history of migration and the partition of the state in 1947.Considering these factors in the present study an attempt has been made to analyze the internal displacement caused by Language movements and Assam movement. KEYWORDS: displacement, conflicts, identity movements, linguistic composition DISCUSSION are concentrated in the different corners of the state. Some of The state of Assam is considered as mini India. It is these Tribes have assimilated themselves and have become connected with main land of India with a narrow patch of the part and parcel of Assamese nationality. -

•Eak-Tet Parenfe

- ■ r " www.inagicvallel l e y . c o m ^ ^ T h l e s b I •Sd cents-. ..........- ^Twin Falls, Idahiiho/98ih year, N o7 ^3 4 4 0 --■ ■■;■ --------------------- - Sanirday,, 1Dcccmbcr 6,'20(B3 ° - - - - T G o o b m o rNING.- n .... C( WKA'I'HKR o p s n :a b s u i s p e c it i n b ) a b y aI s s a u[ l it Today: > Sgt. George Erskine. - -^^o C f^ -Scattere■red rain ByRsbMcal»I M eany-;; “ 1 1 “ ------- - i &^H|jH|b tbday'ana n d : ■ Tlmes^owsrwriter w ' ' •' -Filerm an now ffaces^escape,-aufofotH eft cliafge.s—“ -CountySheriff’y-Departn ■ — to the father’s house Fridiiy] to a ' W ~ t o n i ^I t t, , h ig h in(iuire if he luid seen th • 0 “^ 50,Iowy 335. TWIN FALALLS - A Filer man sus- '• Jackman has been charjiirged \sith Johnson saidaid. Wearing handcuffs, t managed lo get oul of Johnson said. pccted of sasexually abusing a child oone coimt of lewd and 1.lascivious ' the suspect ti PPage A2 “Tile dad said. 'Yeah,, hhe's here,"' and then fle<fleeing from police after C'conduct with a m inor an dI o ne count the car, and Ja a police search failed to ' I his arrest WtWednesday was back in oof injuiy to a cliild, He; inow also locate him; Jolm son said. faces ciiarges of escape aiand grand Police saidnid Friday they learned ’Hie suspect \s-as hidirling bi'l'.iiid J , M a g i c V a i . -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

'Bihu' in Assam Movement

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 12, No. 1, January-March, 2020. 1-11 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n1/v12n102.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n1.02 The Political role of ‘Bihu' in Assam movement (1979) Debajit Bora Assistant Professor, Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, Jamia Millia Islamia, [email protected], ORCID id: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6424-2522 Abstract This paper aims to understand the political role of Assamese traditional performance ‘Bihu’ during Assam movement in 1979. It argues that beyond its role as Assamese cultural identity, ‘Bihu’ had transformed itself into a political space and fueled upon expanding the idea of Stage Bihu. While looking at the performance as medium of political messaging, the paper brings together the three specific case studies seemingly unknown in the documented cultural history and located in the rural Assam. The idea is to comprehend the larger scope of traditional performance in accommodating political events. The debates are being weaved together through theoretical frames of historian Eric Hobsbawm’s ‘Inventing tradition’ Thomas Postlewait’s ‘theatre event’ in order to see the transformation and changes within the repertoire of Bihu. The paper tries to resurrect an alternative historical discourse, often neglected by the dominant historical cannons. Keywords: performance, identity, Assam movement, politics, Assam. Introduction Assam movement, 1979 had emerged as one of the strong identity assertion movement in post Independent India mainly revolved around the issue illegal migration from Bangladesh. On June 8, 1979, the All Assam Students Union (AASU) sponsored a 12-hour general strike (bandh) in the state to demand the "detection, disenfranchisement and deportation" of foreigners. -

Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam

ISSN. 0972 - 8406 61 The NEHU Journal, Vol XII, No. 2, July - December 2014, pp. 61-76 Event, Memory and Lore: Anecdotal History of Partition in Assam BINAYAK DUTTA * Abstract Political history of Partition of India in 1947 is well-documented by historians. However, the grass root politics and and the ‘victim- hood’ of a number of communities affected by the Partition are still not fully explored. The scholarly moves to write alternative History based on individual memory and family experience, aided by the technological revolution have opened up multiple narratives of the partition of Assam and its aftermath. Here in northeast India the Partition is not just a History, but a lived story, which registers its presence in contemporary politics through songs, poems, rhymes and anecdotes related to transfer of power in Assam. These have remained hidden from mainstream partition scholarship. This paper seeks to attempt an anecdotal history of the partition in Assam and the Sylhet Referendum, which was a part of this Partition process . Keywords : sylhet, partition, referendum, muslim league, congress. Introduction HVSLWHWKHSDVVDJHRIPRUHWKDQVL[W\¿YH\HDUVVLQFHWKHSDUWLWLRQ of India, the politics that Partition generated continues to be Dalive in Assam even today. Although the partition continues to be relevant to Assam to this day, it remains a marginally researched area within India’s Partition historiography. In recent years there have been some attempts to engage with it 1, but the study of the Sylhet Referendum, the event around which partition in Assam was constructed, has primarily been treated from the perspective of political history and refugee studies. 2 ,W LV WLPH +LVWRU\ ZULWLQJ PRYHG EH\RQG WKH FRQ¿QHV RI political history. -

Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations Under Colonial Rule

IRSH 51 (2006), Supplement, pp. 143–172 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859006002641 # 2006 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Power Structure, Discipline, and Labour in Assam Tea Plantations under Colonial Rule Rana P. Behal The tea industry, from the 1840s onwards the earliest commercial enterprise established by private British capital in the Assam Valley, had been the major employer of wage labour there during colonial rule. It grew spectacularly during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when tea production increased from 6,000,000 lb in 1872 to 75,000,000 lb in 1900 and the area under tea cultivation expanded from 27,000 acres to 204,000 acres.1 Employment of labour in the Assam Valley tea plantations increased from 107,847 in 1885 to 247,760 in 1900,2 and the industry continued to grow during the first half of the twentieth century. At the end of colonial rule the Assam Valley tea plantations employed nearly half a million labourers out of a labour population of more than three-quarters of a million, and more than 300,000 acres were under tea cultivation out of a total area of a million acres controlled by the tea companies.3 This impressive expansion and the growth of the Assam Valley tea industry took place within the monopolistic control of British capital in Assam. An analysis of the list of companies shows that in 1942 84 per cent of tea estates with 89 per cent of the acreage in the Assam Valley were controlled by the European managing agency houses.4 Throughout India, thirteen leading agency houses of Calcutta controlled over 75 per cent of total tea production in 1939.5 Elsewhere I have shown that the tea companies reaped profits over a long time despite fluctuating international prices and slumps.6 One of the most notable features of the Assam Valley tea plantations was that, unlike in the cases of most of the other major industries such as jute, textiles, and mining in British India, it never suffered from a complete 1. -

Actual and Ideal Fertility Differential Among Natives, Immigrants, and Descendants of Immigrants in a Northeastern State of India

Accepted: 24 January 2019 DOI: 10.1002/psp.2238 RESEARCH ARTICLE Actual and ideal fertility differential among natives, immigrants, and descendants of immigrants in a northeastern state of India Nandita Saikia1,2 | Moradhvaj2 | Apala Saha2,3 | Utpal Chutia4 1 World Population Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Abstract Laxenburg, Austria Little research has been conducted on the native‐immigrant fertility differential in 2 Centre for the Study of Regional low‐income settings. The objective of our paper is to examine the actual and ideal fer- Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, India tility differential of native and immigrant families in Assam. We used the data from a 3 Department of Geography, Institute of primary quantitative survey carried out in 52 villages in five districts of Assam during Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 2014–2015. We performed bivariate analysis and used a multilevel mixed‐effects lin- India 4 Department of Anthropology, Delhi ear regression model to analyse the actual and ideal fertility differential by type of vil- University, Delhi, India lage. The average number of children ever‐born is the lowest in native villages in Correspondence contrast to the highest average number of children ever‐born in immigrant villages. Dr. Nandita Saikia, Post Doc Scholar, The likelihood of having more children is also the highest among women in immigrant International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Schlossplatz 1, 2361 Laxenburg, villages. However, the effect of religion surpasses the effect of the type of village the Austria. women reside in. Email: [email protected] Funding information KEYWORDS Indian Council of Social Science Research, Assam, fertility, immigrants, India, native, religion Grant/Award Number: RESPRO/58/2013‐14/ ICSSR/RPS 1 | INTRODUCTION fertility of immigrants and their descendants can be an important indi- cator of social integration over time (Dubuc, 2012).