Messages from My Father-In-Law: Indexing Membership and Proximity in Long-Distance Voicemails

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

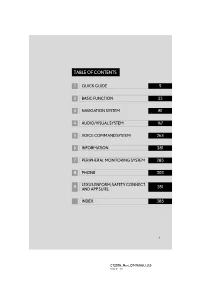

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 QUICK GUIDE 9 2 BASIC FUNCTION 33 3 NAVIGATION SYSTEM 81 4 AUDIO/VISUAL SYSTEM 167 5 VOICE COMMAND SYSTEM 263 6 INFORMATION 281 7 PERIPHERAL MONITORING SYSTEM 285 8 PHONE 303 LEXUS ENFORM, SAFETY CONNECT 9 351 AND APP SUITE INDEX 385 1 CT200h_Navi_OM76146U_(U) 14.06.17 11:11 Introduction NAVIGATION SYSTEM OWNER’S MANUAL This manual explains the operation of the Navigation System. Please read this manual carefully to ensure proper use. Keep this manual in your vehicle at all times. The screen shots in this document and the actual screens of the navigation system dif- fer depending on whether the functions and/or a contract existed and the map data available at the time of producing this document. Please be aware that the content of this manual may be different from the navigation system in some cases, such as when the system’s software is updated. NAVIGATION SYSTEM The Navigation System is one of the most technologically advanced vehicle accesso- ries ever developed. The system receives satellite signals from the Global Positioning System (GPS) operated by the U.S. Department of Defense. Using these signals and other vehicle sensors, the system indicates your present position and assists in locating a desired destination. The navigation system is designed to select efficient routes from your present starting location to your destination. The system is also designed to direct you to a destination that is unfamiliar to you in an efficient manner. The system uses DENSO maps. The cal- culated routes may not be the shortest nor the least traffic congested. -

Story: Part 1

Log in Page Discussion Read View source View history Search Summertime Saga Wiki Main story: Part 1 Contents [hide] 1 Requirements Home Back to site 2 Story Recent changes 3 Optional scenes 4 Pregnancies Navigation 4.1 Maria Walkthrough 4.2 Josephine Characters Locations Items Requirements Minigames Dexterity up to 4 Tools & Extensions Strength up to 5 DarkCookie's Stream F.A.Q. Story Tools What links here The main story starts after the prologue, on the second day. Related changes Special pages The Bad Guys Printable version Allow 2 days to pass. Permanent link Page information 1. The police officer Harold is reassuring the landlady in the kitchen, and you get to know his partner, Yumi. Suspicion is growing thicker around your father’s death and the debt he incurred. Allow 2 days to pass. 2. The breakfast is ruined by two Russian‐accented thugs at the front door. While Debbie’s making a statement in the kitchen, Jenny has her own opinion in the hallway. Allow 5 days to pass. 3. No sooner have you crossed the home threshold than the intimidation resumes. The housemates aren’t much more confident. Veni, Vidi, Tony This event is randomly triggered after an 11-day delay. 4. It could have been just another day but Igor and Dimitri decided otherwise. Your rescue is due to Tony’s interposition. After recounting the incident to Debbie and Jenny, you find solace in your bed. 5. Next day, the least you ought to do is thank Tony in his restaurant. A deliveryman’s position just opened up: with the bike purchased at Consum-R, distribute the pizza in the right order to be hired. -

The Forensic Teacher Magazine Issue 37

The Forensic Teacher Magazine Issue 37 Page left intentionally blank. This magazine is best viewed with the pages in pairs, side by side (View menu, page display, two- up), zooming in to see details. Odd numbered pages should be on the right. you reallyThe presents wanted! The Forensic science Kit EXAMINE THE EVIDENCE & SOLVE THE CASE + Includes real forensic tests + Dust evidence for prints to match against suspect prints Forensic + Study the police case file Teacher Magazine to solve the murder of + Test fabric samples for the Missy Hammond* presence of blood. KIT 2 SIZES smALL cLAssroom Up to 4 peopLe Up to 40 stUDents $55$ 325 BOTH SIZES COME WITH FREE, CLASSROOM-TESTED LESSON PLANS RECOMMENDED FOR 9th grADe & Up Spring 2021 * internet access is required to view the case file shop.crimescene.com // [email protected] $5.95 US/$6.95 Can you reallyThe presents wanted! Forensic science Kit EXAMINE THE EVIDENCE & SOLVE THE CASE + Includes real forensic tests + Dust evidence for prints to match against suspect prints + Study the police case file to solve the murder of + Test fabric samples for the Missy Hammond* presence of blood. KIT 2 SIZES smALL cLAssroom Up to 4 peopLe Up to 40 stUDents $55 $325 BOTH SIZES COME WITH FREE, CLASSROOM-TESTED LESSON PLANS RECOMMENDED FOR 9th grADe & Up * internet access is required to view the case file shop.crimescene.com // [email protected] Spring 2015 The Forensic Teacher • Spring 2021 $5.95 US/$6.95 Can The Volume 14, Number 37, Spring 2021 The Forensic Teacher Magazine is published and owned by Wide Open Minds Educational Services, LLC. -

Remotely Controlled

The broken C I Sidling and secretaries A harmless three-hour tour T Y Reality TV on the Red Planet That faithful moose passes by “Darn tootin’, I love Fig Newtons” REMOTELY CONTROLLED 17 Winter 2015 ISSN 1916-3304 The broken C I W i n t e r 2 0 15 Issue 17 T Y The Broken City A r t Contributor : , ISSN 1916-3304, is published semiannually Bill Wolak out of Toronto, Canada, appearing sporadically in print, but The Broken City (“Tasting the Whispers” on the front cover and always at: www.thebrokencitymag.com. Rights to individual Love Opens the Hands “Sand Dreaming of Dew” on page 8) has just published works published in remain the property of his twelfth book of poetry, entitled , the author and cannot be reproduced without their consent. with Nirala Press. Recently, he was a featured poet at The All other materials © 2015. All rights reserved. All wrongs Mihai Eminescu International Poetry Festival in Craiova, reversed. O n t h e W e b : Romania. Mr. Wolak teaches Creative Writing at William PatersonD i s c l aUniversity i m e r : in New Jersey. Owww.thebrokencitymag.com n m o b i l e d e v i c e s : Remotely Controlled Though we arrived at this issue’s title independently, we Sissuu.com/thebrokencity u b m i s s i o n Guidelines: should point out that is also the name Cof oan n unaf�iliated t e n t s : book by Aric Sigman. Correspondencewww.thebrokencitymag.com/submissions.html: Poetry .....3-7, 12, 13 [email protected] Robot .....8 O n Tw i t t e r : Fiction .....9 Essay .....11 @brokencitymag The Broken City I n t h i s i s s u e : Breakfast Clubbed is currently accepting submissions for its summer 2016 edition: . -

THE COLLECTED LETTERS and UNPUBLISHED WRITINGS of KARIN PANKREEZ, NOVELIST ASPIRANT Jason Shrontz Northern Michigan University

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 2011 THE COLLECTED LETTERS AND UNPUBLISHED WRITINGS OF KARIN PANKREEZ, NOVELIST ASPIRANT Jason Shrontz Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Shrontz, Jason, "THE COLLECTED LETTERS AND UNPUBLISHED WRITINGS OF KARIN PANKREEZ, NOVELIST ASPIRANT" (2011). All NMU Master's Theses. 505. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/505 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE COLLECTED LETTERS AND UNPUBLISHED WRITINGS OF KARIN PANKREEZ, NOVELIST ASPIRANT By Jason Shrontz THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Graduate Studies Office 2011 SIGNATURE OF APPROVAL FORM This thesis by Jason Shrontz is recommended for approval by the student’s Thesis Committee and Department Head in the Department of English and by the Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies. Committee Chair: Dr. Stephen Burn Date First Reader: Dr. Lee Siegel Date Second Reader: Rebecca Johns Trissler Date Department Head: Dr. Raymond Ventre Date Dean of Graduate Studies: Dr. Terrance L Seethoff Date OLSON LIBRARY NORTHERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY THESIS DATA FORM In order to catalog your thesis properly and enter a record in the OCLC international bibliographic data base, Olson Library must have the following requested information to distinguish you from others with the same or similar names and to provide appropriate subject access for other researchers. -

Communications Training Manual

_____________________________________________________________________________ ALBANY POLICE DEPARTMENT COMMUNICATIONS TRAINING MANUAL SERVICE PROFESIONALISM PRIDE TEAMWORK DEDICATION ______________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ Page intentionally left blank ______________________________________________________________________ COMMUNICATIONS TRAINING MANUAL 2 _____________________________________________________________________________ CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION The term "Public Safety Dispatcher" describes today's professional whose skills combine those of a radio dispatcher, telephone call-taker and computer specialist. Our goal is improved public safety by increasing communication accuracy and decreasing response time. This goal very much involves you. If you have not previously used a Records Incident Management System (RIMS), you will be introduced to the most modern method of public safety dispatching. Although it can appear intimidating, it is a user-friendly system that will greatly increase your efficiency. You can't break the computer by pressing the wrong button. If you do make a mistake, it can be fixed. You will find the RIMS to be faster, more exact, and much easier to use than the outdated manual dispatching system. The RIMS system affords all terminal users’ quick access to a myriad of computer listed files. Users can query the status of all units and calls from any terminal in the system. One can also view and/or print out a history of any incident in chronological order. What used to take hours of handwriting and typing now only takes seconds to note, and the computer stores the data. The term "call-taker" refers to the individual who receives the call from the reporting party, extracting thorough and accurate information for the proper allocation of resources. The "dispatcher", by use of the police radio, allocates departmental resources predicated on the information received from the call-taker and/or field personnel. -

Appellant's Brief

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGINIA CHARLESTON, WEST VIRGINIA No. 34770 STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA, Plaintiff Below - Respondent, i~... ~,l;;' ~ I . r JUN ::i ...... VS. I.j . l l _ t RORY L. PERRY II, CLERK ) •...... SUPREME COLJRT OF APPEALS L,~_ OF,!VEST VIRIGINIA DALLAS HUGHES, Defendant Below - Petitioner. CIRCUIT COURTOF RALEIGH COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA CASE NO. 04-F-285-H BRIEF OF APPELLANT . Submitted by: John J. Mize WVSB# 10091 Mize Law Firm, PLLC Counsel for Appel/ant 106 Y2 South Heber Street Suite One Beckley, WV 25801 (304) 255-6493 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities. 3 Kind of Proceedings and Nature of Rulings Below 4 Statement of Facts . 7 Assignments of Error and the Manner in Which They Were Decided. 13 Points and Authorities 14 A~ume~ 16 Conclusion 48 Request for Relief 50 THE DEFENDANT WAS REQUIRED TO DEFEND AGAINST BOTH FELONY MURDER AND PREMEDITATED MURDER EVEN THOUGH DEFENDANT HAD NO NOTICE OF THE FELONY MURDER CHARGE BECAUSE THE INDICTMENT RETURNED AGAINST DEFENDANT CHARGED HIM WITH PREMEDITATED MURDER BUT DID NOT CHARGE HIM WITH FELONY MURDER. 16 The defendant was not provided with fair and adequate notice that he would be required to defend a charge of felony murder because the indictment charged the defendant with premeditated first degree murder only. 16. The trial court abused its discretion by not granting defendant's motion to have the State elect between premeditated and felony murder either during the trial or at the close of evidence when the defendant made a particularized showing of the prejudice that would result from a failure to elect. -

In the Supreme Court of Florida Case No. Sc05-587 Roy Lee Mcduffie

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA CASE NO. SC05-587 ROY LEE MCDUFFIE Appellant, v. STATE OF FLORIDA Appellee. ___________________________________________________ CORRECTED ANSWER BRIEF OF APPELLEE ON APPEAL FROM THE SEVENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR VOLUSIA COUNTY, FLORIDA ___________________________________________________ CHARLES J. CRIST, JR. ATTORNEY GENERAL COUNSEL FOR RESPONDENT BARBARA C. DAVIS Fla. Bar No. 410519 ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL 444 SEABREEZE BLVD., SUITE 500 DAYTONA BEACH, FLORIDA 32114 (386)238-4990 FAX - (386) 226-0457 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................ii STATEMENT OF THE CASE ....................................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE FACTS .....................................10 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................59 ARGUMENTS ..................................................62 POINT I THE TRIAL COURT CONDUCTED AN ADEQUATE RICHARDSON HEARING AND IMPOSED AN APPROPRIATE REMEDY FOR THE DEFENSE DISCOVERY VIOLATION; ERROR, IF ANY, WAS HARMLESS ....................62 POINT II THE TRIAL COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN ADMITTING THE TESTIMONY OF ALEX MATIAS IDENTIFYING McDUFFIE OR IN LIMITING CROSS-EXAMINATION REGARDING OTHER SUSPECTS .......67 POINT III THE TRIAL COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN LIMITING PRESENTATION OF CRIMINAL ACTS OF OTHER PERSONS ............72 POINT IV THE TRIAL COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN ADMITTING THE TESTIMOMY OF DAVID PEDERSON ...........................78 -

21-5211 Questioned Documents Examination

P.O. Box 650820 Collaborative Testing Services, Inc Sterling, VA 20165-0820 e-mail: [email protected] FORENSIC TESTING PROGRAM Telephone: +1-571-434-1925 Web site: www.cts-forensics.com Questioned Documents Examination Test No. 21-5211 Summary Report Each sample set consisted of a questioned robbery note (Q1) and a known spiral notepad (K1) for examination and analysis. Participants were requested to examine the items to determine if the questioned note could have originated from the recovered notepad. Data were returned from 176 participants and are compiled into the following tables: Page Manufacturer's Information 2 Summary Comments 3 Table 1: Examination Results 4 Table 2: Methods and Observations 8 Table 3: Conclusions 63 Table 4: Additional Comments 87 Appendix: Data Sheet This report contains the data received from the participants in this test. Since these participants are located in many countries around the world, and it is their option how the samples are to be used (e.g., training exercise, known or blind proficiency testing, research and development of new techniques, etc.), the results compiled in the Summary Report are not intended to be an overview of the quality of work performed in the profession and cannot be interpreted as such. The Summary Comments are included for the benefit of participants to assist with maintaining or enhancing the quality of their results. These comments are not intended to reflect the general state of the art within the profession. Participant results are reported using a randomly assigned "WebCode". This code maintains participant's anonymity, provides linking of the various report sections, and will change with every report. -

“Coffee Is Not Coffee! Coffee Is Sex!” – Kodade Identiteter Och Intertextuellt Kaos I Seinfeld Innehållsförteckning 1.1 Inledning S

Lunds Universitet Pontus Gunnarson Språk- och litteraturcentrum FIVK01 Filmvetenskap Handledare: Lars-Gustaf Andersson 2008-01-17 “Coffee is not coffee! Coffee is sex!” – Kodade identiteter och intertextuellt kaos i Seinfeld Innehållsförteckning 1.1 Inledning s. 3 1.2 Frågeställning s. 4 1.3 Metod s. 4 1.4 Teori s. 5 1.5 Presentation av primärmaterial s. 9 2.1 Seinfelds karaktärer s. 9 2.1.1 Jerry Seinfeld: Komikern s. 10 2.1.2 George Costanza: Neurotikern s. 11 2.1.3 Cosmo Kramer: Galningen s. 11 2.1.4 Elaine Benes: Moralisten s. 12 3.1 Postmodern humor s. 13 3.1.1 Tecken s. 13 3.1.2 Parallellisering s. 15 4.1 Identitetskodning s. 17 4.1.1 Kommodifiering av identitet s. 18 4.1.2 Konstruerad identitet s. 20 4.1.3 Intertextuell identitet s. 23 5.1 Slutdiskussion s. 27 6.1 Källförteckning s. 29 6.1.1 Primärmaterial s. 29 6.1.2 Sekundärmaterial, filmer s. 29 6.1.3 Sekundärmaterial, TV-serier s. 30 6.1.4 Sekundärmaterial, tryckt s. 31 6.1.5 Sekundärmaterial, otryckt s. 32 6.1.6 Övrigt s. 32 2 1.1 Inledning 90-talets kanske allra populäraste komediserie stavas Seinfeld . Det kanske mest uppseendeväckande med serien är handlingen; Seinfeld säger sig handla om ingenting . Intresset hos mig väcktes dock av en annan anledning; bristen på moraliskt budskap. Seinfeld är i sin genre en föregångare på den här punkten, en frisk fläkt av förändring inom komediseriens värld som än idag mer ofta än sällan levererar ett samhällsfrämjande budskap i slutet av varje avsnitt: Populära exempel som Vänner (som möjligtvis kan tävla med Seinfeld i antal tittarsiffror), Full House , Joey , That 70’s Show och t.o.m. -

Sydney Program Guide

6/21/2019 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_ELEVEN_Guide?psStartDate=07-Jul-19&psEndDate=13-… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 07th July 2019 06:00 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 06:05 am Cardfight!! Vanguard (Rpt) G Turn 21 - Fake Fight Chrono, accompanied by Tokoha and Shion, join the mini-championship held at the headquarters of United Sanctuary. 06:30 am Transformers: Robots In Disguise (Rpt) G Graduation Exercises Slipstream and Jetstorm accidentally put Drift in harm's way when they try to prove their worth. 06:55 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:00 am Treasure Island (Rpt) G The Algae Swamp Adventure on high seas to the Caribbean with young Jim Hawkins, Long John Silver and the rest of the crew as they search for the hidden treasure of Captain Flint. 07:25 am Toasted TV G Want the lowdown on what's hot in the playground? Join the team for the latest in pranks, movies, music, sport, games and other seriously fun stuff! Featuring a variety of your favourite cartoons. 07:30 am Littlest Pet Shop (Rpt) G It's A Happy, Happy, Happy, Happy World Sunil's pursuit of happiness leads him through the city with the other pets. -

Gay Era (Lancaster, PA)

LGBT History Project of the LGBT Center of Central PA Located at Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Documents Online Title: Gay Era (Lancaster, PA) Date: November 1977 Location: LGBT-001 Joseph W. Burns Collection Periodicals Collection Contact: LGBT History Project Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] Dy Urawrord Barton Now under new ownership formerly “The Dandelion Tree” In the News KU KLUX KLAN CALLS least two major denominations have actually ordained homosexuals into FOR EXECUTION OF HOMOSEXUALS the ministry. The first was the HOUSTON—A tape-recorded tele 1.8 million member United Church of phone message from a Ku Klux Klan Christ which ordained a male preach bookstore in Pasadena, California, ing queer five years ago, and the urges the execution of all homosex other is the Episcopalian church, uals. It is not known whether the which recently ordained a female call for the execution of gay people homosexual, or lesbian, as a priest. is official KKK policy. However, "The Ku Klux Klan does not have KKK members have offered their serv to rely on the feelings or thoughts ices to protect anti-gay singer of man, nor do we need to experience Anita Bryant at public appearances a dialogue with some Jewish psychia and recently did so at a Huntington, trist or rabbi who is mentally warp West Virginia, rally. ed anyway. We rely upon the age- The phone message states that proven and reliable law of God. "The Ku Klux Klan is not embarrassed "The law on homosexuality states: to admit that we endorse and seek 'That if a man also lie with man the execution of all homosexuals.