November 2014 1 President’S View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

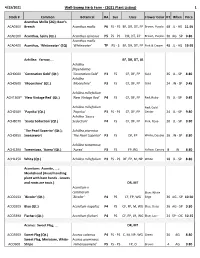

WSHF Catalog

4/23/2021 Well-Sweep Herb Farm - (2021 Plant Listing) 1 Stock # Common Botanical HA Sun Uses Flower ColorHT When Price Acanthus Mollis (2Q); Bear's ACA030X Breech Acanthus mollis P6 FS - PS BF, DR, DT, FP Brown, Purple- 48 JL - AG 11.95 ACA010X Acanthus, Spiny (Qt.) Acanthus spinosus P5 FS - PS DR, DT, FP Brown, Purple- 30 AG - SP 9.80 Acanthus mollis ACA040X Acanthus, `Whitewater' (2Q) `Whitewater' TP PS - S BF, DR, DT, FP Pink & Cream 48 JL - AG 19.95 Achillea: Yarrow, ... BF, DR, DT, LB Achillea filipendulina ACH000X `Coronation Gold' (Qt.) `Coronation Gold' P3 FS CF, DF, FP Gold 36 JL - SP 8.80 Achillea ACH050X `Moonshine' (Qt.) `Moonshine' P3 FS CF, DF, FP Gold 24 JN - SP 9.45 Achillea millefolium ACH130X* `New Vintage Red' (Qt.) `New Vintage Red' P4 FS CF, DF, FP Red, Ruby- 15 JL - SP 9.45 Achillea millefolium Red; Gold ACH250X `Paprika' (Qt.) `Paprika' P3 FS - PS CF, DF, FP Center 24 JL - SP 9.80 Achillea `Saucy ACH807X `Saucy Seduction' (Qt.) Seduction' P4 FS CF, DF, FP Pink, Rose- 20 JL - SP 9.80 `The Pearl Superior' (Qt.); Achillea ptarmica ACH095X Sneezewort `The Pearl Superior' P3 FS DF, FP White; Double 16 JN - SP 8.80 Achillea tomentosa ACH120X Tomentosa, `Aurea' (Qt.) `Aurea' P3 FS FP, RG Yellow, Canary- 8 JN 8.80 ACH125X White (Qt.) Achillea millefolium P3 FS - PS DF, FP, M, NP White 18 JL - SP 8.80 Aconitum: Aconite, ... ; Monkshood (Avoid handling plant with bare hands - Leaves and roots are toxic.) DR, MT Aconitum x cammarum Blue; White ACO015X `Bicolor' (Qt.) `Bicolor' P4 PS CF, FP, WG Edge 36 AG - SP 10.50 ACO020X Blue (Qt.) Aconitum napellus P4 PS CF, FP, M, WG Blue, Deep- 36 AG - SP 9.80 ACO339X Fischeri (Qt.) Aconitum fischeri P4 PS CF, FP, LB, WG Blue, Lav.- 24 SP - OC 10.15 Acorus: Sweet Flag, .. -

Histochemical and Phytochemical Analysis of Lamium Album Subsp

molecules Article Histochemical and Phytochemical Analysis of Lamium album subsp. album L. Corolla: Essential Oil, Triterpenes, and Iridoids Agata Konarska 1, Elzbieta˙ Weryszko-Chmielewska 1, Anna Matysik-Wo´zniak 2 , Aneta Sulborska 1,*, Beata Polak 3 , Marta Dmitruk 1,*, Krystyna Piotrowska-Weryszko 1, Beata Stefa ´nczyk 3 and Robert Rejdak 2 1 Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, University of Life Sciences, Akademicka 15, 20-950 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (E.W.-C.); [email protected] (K.P.-W.) 2 Department of General Ophthalmology, Medical University of Lublin, Chmielna 1, 20-079 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (A.M.-W.); [email protected] (R.R.) 3 Department of Physical Chemistry, Medical University of Lublin, Chod´zki4A, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] (B.P.); offi[email protected] (B.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (M.D.); Tel.: +48-81-445-65-79 (A.S.); +48-81-445-68-13 (M.D.) Abstract: The aim of this study was to conduct a histochemical analysis to localize lipids, terpenes, essential oil, and iridoids in the trichomes of the L. album subsp. album corolla. Morphometric examinations of individual trichome types were performed. Light and scanning electron microscopy Citation: Konarska, A.; techniques were used to show the micromorphology and localization of lipophilic compounds and Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; iridoids in secretory trichomes with the use of histochemical tests. Additionally, the content of Matysik-Wo´zniak,A.; Sulborska, A.; essential oil and its components were determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry Polak, B.; Dmitruk, M.; (GC-MS). -

Lavender Quiz: Questions and Answers

kupidonia.com Lavender Quiz: questions and answers Lavender Quiz: questions and answers - 1 / 4 kupidonia.com 1. What is lavender? A vegetable A fruit A flower 2. What is the most widely cultivated species of lavender? Lavandula stoechas Lavandula pinnata Lavandula angustifolia 3. Which family does lavender belong to? Eudicots Asterids Lamiaceae 4. In what year L. pinnata and L. carnosa were recognized? 1937 1753 1790 5. How many subgenera is lavender considered to have? 4 2 Lavender Quiz: questions and answers - 2 / 4 kupidonia.com 3 6. In what type of soil do lavenders bloom the best? Sandy soil Dry soil Both are true 7. Which lavender is used for producing lavender essential oil used in balms, perfumes and cosmetics? Lavandula angustifolia Lavandula multifida Lavandula latifolia 8. In which century was lavender introduced to England? 1600s 1800s 1500s 9. In practices of herbalism, what is the use of lavender? For curing insomnia For curing Roehmheld's syndrome Both are true 10. What have the ancient Greeks called the lavender herb? Dohuk Nardus Naarda Lavender Quiz: questions and answers - 3 / 4 kupidonia.com Lavender Quiz: questions and answers Right answers 1. What is lavender? A flower 2. What is the most widely cultivated species of lavender? Lavandula angustifolia 3. Which family does lavender belong to? Lamiaceae 4. In what year L. pinnata and L. carnosa were recognized? 1790 5. How many subgenera is lavender considered to have? 3 6. In what type of soil do lavenders bloom the best? Both are true 7. Which lavender is used for producing lavender essential oil used in balms, perfumes and cosmetics? Lavandula angustifolia 8. -

Effect of Heat Shock on Ultrastructure and Calcium Distribution in Lavandula Pinnata L. Glandular Trichomes. By

Effect of heat shock on ultrastructure and calcium distribution in Lavandula pinnata L. glandular trichomes. By: S.S. Huang, Bruce K. Kirchoff and J.P. Liao Huang, S-S, Kirchoff, B.K., and J-P Liao. 2013. Effect of heat shock on ultrastructure and calcium distribution in Lavandula pinnata L. glandular trichomes. Protoplasma. 250(1), 185- 196. DOI: 10.1007/s00709-012-0393-7 Made available courtesy of Springer Verlag. The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com. ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Springer Verlag. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: The effects of heat shock (HS) on the ultrastructure and calcium distribution of Lavandula pinnata secretory trichomes are examined using transmission electron microscopy and potassium antimonate precipitation. After 48-h HS at 40°C, plastids become distorted and lack stroma and osmiophilic deposits, the cristae of the mitochondria become indistinct, the endoplasmic reticulum acquires a chain-like appearance with ribosomes prominently attached to the lamellae, and the plasma and organelle membranes become distorted. Heat shock is associated with a decrease in calcium precipitates in the trichomes, while the number of precipitates increases in the mesophyll cells. Prolonged exposure to elevated calcium levels may be toxic to the mesophyll cells, while the lack of calcium in the glands cell may deprive them of the normal protective advantages of elevated calcium levels. The inequality in calcium distribution may result not only from uptake from the transpiration stream, but also from redistribution of calcium from the trichomes to the mesophyll cells. -

2016 Catalog

Well-Sweep Herb Farm 2016 Catalog $3.00 ‘Hidcote’ Lavender Hedge & Orange Calendula Helleborus - ‘Peppermint Ice’ Gentiana - ‘Maxima’ Trumpet Gentian Farm Hours Monday - Saturday, 9:00 to 5:00. Closed Sundays and Holidays. Special Openings: Sundays 11 - 4, April 24 - July 31 & December only. The farm is open year-round, but please call before stopping by January - March. Phone: (908) 852-5390 Fax: (908) 852-1649 www.wellsweep.com ‘Judith Hindle’ Pitcher Plant 205 Mount Bethel Rd, Port Murray, New Jersey 07865-4147 ‘Blackcurrant Swirl’ Double Datura Citrus - Calamondin Orange ‘Yellow Trumpet’ ‘Well-Sweep Pitcher Plant Miniature Purple’ Basil ‘Bartzella’ Itoh Peony ‘Tasmanian Angel’ Acanthus ‘King Henry’ Venus Fly Trap Our Sales Area ‘Tomato Soup’ Cone Flower WELCOME To Well-Sweep Herb Farm! Our farm, a family endeavor, is located in the picturesque mountains of Warren County and is home Our Plants to one of the largest collections of herbs and perenni- Our plants are grown naturally, without chemi- als in the country. Germinating from the seed of cal pesticides or fungicides. All plants are shipped prop- handed down tradition and hobby - to a business that erly labeled and well-rooted in three inch pots or quart has flourished, 2016 proclaims our 47th year. containers as noted in the catalog by (Qt.). Weather From around the globe, with a breadth of Acan- permitting, our widest selection of herb plants and pe- thus to Zatar, our selection spans from the familiar rennials are available for purchase around May 15th. and unusual to the rare and exotic. This season we are introducing 76 intriguing new plants to our collection Our News which now tops 1,911 varieties. -

Plant List 2014

%1.00 ! MINNESOTA LANDSCAPE ARBORETUM AUXILIARY SPRING PLANT SALE Saturday, May 10 & Sunday, May 11, 2014 Table of Contents! th Year !! Shade Perennials...................................2-4! Our 46 Martagon Lilies……………………….……..…5 Ferns…………………………….………………….5! PLANT SALE! HOURS! Ground Covers for Shade………………..…5 Saturday, May 10, 9 am to 4 pm Sun Perennials……………………………….6-9! Sunday, May 11!, 9 am to 4 pm Annuals ……………………………………….…10! • The sale will be held at the Arboretum’s picnic shelter area Rock Garden Perennials……………………11! near the Marion Andrus Prairie Plants……………………………………11 Learning Center.! • Come early for best selection.! Hemerocallis (Daylily)………………………12! • Bring carrying containers for Water Gardens…………………………………12! your purchases: boxes, wagons, carts.! Paeonia (Peony)……………………………13-14! • There will be a pickup area where you can drive up and load Roses........................................................15! your plants.! Hosta...................................................16-17! • We also have a few golf carts with volunteers to drive you and Woodies:! your plants to your car.! !Vines……………………………………….18! ! PAYMENT !Trees & Shrubs...........................18-19! • Please assist us in maximizing Ornamental Grasses…………………………21! our support of the MLA by using cash or checks. However, if you Herbs..................................................24-25! wish to use a credit card, we gladly accept Visa, MasterCard, Vegetables..........................................26-27! Amex and Discover.! ! • Volunteers will make a list of your purchases which you will hand to a cashier for payment.! • Please keep your receipt as you may need to show it to a volunteer as you exit.! • There will be an Express Lane for purchases of 10 items or fewer.! SHADE PERENNIALS Interest in Shade Gardening continues to grow as more homeowners are finding AQUILEGIA vulgaris ‘Nora Barlow’!(European Columbine)--18-30” their landscapes becoming increasingly shady because of the growth of trees and Double flowers in delightful combination of red, pink, and green. -

Lavender (Lavandula Spp.) Catherine J

The Longwood Herbal Task Force (http://www.mcp.edu/herbal/) and The Center for Holistic Pediatric Education and Research (http://www.childrenshospital.org/holistic/) Lavender (Lavandula spp.) Catherine J. Chu and Kathi J. Kemper, MD, MPH Principal Proposed Uses: Sedative and anxiolytic; antimicrobial Other Proposed Uses: Analgesic, anticonvulsant, and antidepressant; cholagogue, antispasmodic and digestive aid; antioxidant; anti-inflammatory; cancer chemopreventative; insecticide; aphrodisiac Overview Lavender’s essential oil is commonly used in aromatherapy and massage. Its major clinical benefits are on the central nervous system. Many studies conducted on both animals and humans support its use as a sedative, anxiolytic and mood modulator. Lavender oil has in vitro antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi and some insects. Lavender’s essential oil exerts spasmolytic activity in smooth muscle in vivo, supporting its historical use as a digestive aid. Particular chemical constituents of lavender have potent anticarcinogenic and analgesic properties; its antioxidant effects are less potent than those of other members of its botanical family such as rosemary and sage. Allergic reactions to lavender have been reported. Because of its potent effects on the central nervous system, people with seizure disorders and those using sedative medications should consult a physician before using lavender. Although lavender has traditionally been used to treat symptoms ranging from restlessness to colic in infants and children, systematic studies have not been conducted to test the efficacy and safety of lavender use in infants and children or during pregnancy or lactation. Catherine J. Chu and Kathi J. Kemper, MD, MPH Lavender Page 1 Longwood Herbal Task Force: http://www.mcp.edu/herbal/ Revised July 2, 2001 Historical and Popular Uses Perhaps best known for its popular use in the fragrance industry, lavender also has a long history of medicinal use. -

Catalogue of Type Specimens in the Vascular Plant Herbarium (DAO)

Catalogue of Type Specimens in the Vascular Plant Herbarium (DAO) William J. Cody Biodiversity (Mycology/Botany) Eastern Cereal and Oilseed Research Centre Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada WM. Saunders (49) Building , Central Experimental Farm Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0C6 Canada March 22 2004 Aaronsohnia factorovskyi Warb. & Eig., Inst. of Agr. & Nat. Hist. Tel-Aviv, 40 p. 1927 PALESTINE: Judaean Desert, Hirbeth-el-Mird, Eig et al, 3 Apr. 1932, TOPOTYPE Abelia serrata Sieb. & Zucc. f. colorata Hiyama, Publication unknown JAPAN: Mt. Rokko, Hondo, T. Makino, May 1936, ? TYPE COLLECTION MATERIAL Abies balsamea L. var. phanerolepis Fern. f. aurayana Boivin CANADA: Quebec, canton Leclercq, Boivin & Blain 614, 16 ou 20 août 1938, PARATYPE Abies balsamea (L.) Mill. var. phanerolepis Fern. f. aurayana Boivin, Nat. can. 75: 216. 1948 CANADA: Quebec, Mont Blanc, Boivin & Blain 473, 5 août 1938, HOLOTYPE, ISOTYPE Abronia orbiculata Stand., Contrib. U.S. Nat. Herb. 12: 322. 1909 U.S.A.: Nevada, Clark Co., Cottonwood Springs, I.W. Clokey 7920, 24 May 1938, TOPOTYPE Absinthium canariense Bess., Bull. Soc. Imp. Mosc. 1(8): 229-230. 1929 CANARY ISLANDS: Tenerife, Santa Ursula, La Quinta, E. Asplund 722, 10 Apr. 1933, TOPOTYPE Acacia parramattensis Tindale, Contrib. N.S. Wales Nat. Herb. 3: 127. 1962 AUSTRALIA: New South Wales, Kanimbla Valley, Blue Mountains, E.F. Constable NSW42284, 2 Feb. 1948, TOPOTYPE Acacia pubicosta C.T. White, Proc. Roy. Soc. Queensl. 1938 L: 73. 1939 AUSTRALIA: Queensland, Burnett District, Biggenden Bluff, C.T. White 7722, 17 Aug. 1931, ISOTYPE Acalypha decaryana Leandri, Not. Syst.ed. Humbert 10: 284. 1942 MADAGASCAR: Betsimeda, M.R. -

2016–2017 Seed Exchange Catalog MID-ATLANTIC GROUP He 23Rd Annual Edition for the First Time

The Hardy Plant Society/Mid-Atlantic Group 2016–2017 Seed Exchange Catalog MID-ATLANTIC GROUP he 23rd annual edition for the first time. As you can tions and you will find plants of the Seed Exchange see, this seed program in- your garden can’t do with- TCatalog includes 976 cludes new plants not previ- out! Since some listed seed seed donations contributed ously offered as well as old is in short supply, you are en- by 57 gardeners, from begin- favorites. couraged to place your order ners to professionals. Over We’re sure you’ll enjoy early. 85 new plants were donated perusing this year’s selec- Our Seed Donors Catalog listed seed was generously contributed by our members. Where the initial source name is fol- lowed by “/”and other member names, the latter identifies those who actually selected, collected, cleaned, and then provided descriptions to the members who prepared the catalog. If a donor reported their zone, you will find it in parenthesis. Our sincere thanks to our donors—they make this Seed Exchange possible. Aquascapes Unlimited Gregg, John 3001 (7) Schmitt, Joan 840 / Heffner, Randy 1114 Haas, Joan 1277 (6a) Scofield, Connie 1585 Bartlett, John 45 Henry Foundation 1170 (7) Solow, Sharee 1320 Bennett, Teri 1865 (7) Iroki Garden Squitiere, Paula 2294 (6) Berger, Clara 65 / Deutsch, Cathy 5024 (6b) Stonecrop Gardens, 118 Berkshire Botanical Garden Jellinek, Susan 1607 (7a) Streeter, Mary Ann 926 / Hviid, Dorthe 1143 (5b) Jenkins Arboretum 9985 (7a) Ulmann, Mary Ann 2193 (6) Bittmann, Frank 2937 (6a) Kolo, Fred 507 Umphrey, Catherine 965 (7a) Bowditch, Margaret 84 Kushner, Annetta 522 Urffer, Betsy 1939 Boylan, Rebecca 2137 (6b) Leasure, Charles 543 (7a) Vernick, Sandra 1759 (7) Bricker, Matthew D. -

Portuguese Lavenders Evaluation of Their Potential Use For

UNIVERSITY OF COIMBRA 2012 Portuguese lavenders: evaluation of their potential use for health and agricultural purposes Mónica da Rocha Zuzarte A thesis presented to the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology (Speciality in Plant Physiology) Front cover: Lavandula luisieri growing in the wild at Serra do Caldeirão, Algarve, Portugal. II SUPERVISORS Professor Jorge Manuel Pataca Leal Canhoto Department of Life Sciences Faculty of Sciences and Technology University of Coimbra Professor Lígia Maria Ribeiro Salgueiro Faculty of Pharmacy University of Coimbra This work was financially supported by national funds from FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a T ecnologia under the project CEF/POCI2010/FEDER and by a PhD grant SFRH/BD/40218/2007 to Mónica Rocha Zuzarte supported by QREN funds through the “Programa Operacional Potencial Humano”. III “When you learn, teach, when you get, give” Maya Angelou V I dedicate this thesis to my family and life companion, Rui, for their love, endless support and encouragement. VII AKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a great pleasure to thank everyone who taught, assisted, supported and encouraged me during the course of my PhD project making it a very pleasant journey. I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisors, Prof. Lígia Salgueiro and Prof. Jorge Canhoto, whose expertise, suggestions and constructive commentaries, added considerably to my graduate experience. I would like to thank them for guiding me into the scientific world. A very special thanks goes out to Prof. Jorge Paiva for introducing me to the fantastic world of aromatic and medicinal plants. -

Uma Abordagem Anatômica, Ultraestrutural E Taxonômica

VALÉRIA FERREIRA FERNANDES ESTRUTURAS SECRETORAS FOLIARES EM CASEARIA JACQ.: UMA ABORDAGEM ANATÔMICA, ULTRAESTRUTURAL E TAXONÔMICA Tese apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, para obtenção do título de Doctor Scientiae. VIÇOSA MINAS GERAIS – BRASIL 2016 Aos meus pais, João e Gerusa, pelo amor incondicional, compreensão e incentivos. ii "Se nunca abandonas o que é importante para ti, se te importas tanto a ponto de estares disposto a lutar para obtê-lo, asseguro-te que tua vida estará plena de êxito. Será uma vida dura, porque a excelência não é fácil, mas valerá a pena." Richard Bach iii AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus pela graça da vida, bênçãos recebidas, oportunidades e força diária para enfrentar os obstáculos. Muito obrigada por me permitir discernir que um “não” muitas vezes é um “sim” e por colocar pessoas especiais no meu caminho. A Universidade Federal de Viçosa, em especial ao Programa Pós-Graduação em Botânica, pelo aprendizado proporcionado. A CAPES, pelo apoio financeiro concedido através da bolsa de doutorado. Ao Projeto Floresta-Escola SECTES/UNESCO/HidroEX/FAPEMIG), sob coordenação do Prof. Dr. João Meira Neto, pelo suporte financeiro. Aos meus queridos pais, João e Gerusa, por acreditarem em meus sonhos e ideais, pelos exemplos de determinação, honestidade e pelo amor incondicional. Lembro-me, desde criança, de enfatizarem que o conhecimento é a maior riqueza que uma pessoa pode conquistar e tenho certeza que estavam certos. A vocês, minha eterna gratidão e amor. As minhas irmãs, Emília e Fernanda, pelo amor, carinho, apoio e incentivos. A minha sobrinha, Maria Eduarda, por me mostrar uma nova forma de amor. -

Calcium Distribution and Function in the Glandular Trichomes of Lavandula Pinnata L

Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 137(1), 2010, pp. 1–15 Calcium distribution and function in the glandular trichomes of Lavandula pinnata L. Shan-Shan Huang1,2 The Institute of Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou, 510520, China Jing-Ping Liao South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, 510650, China Bruce K. Kirchoff University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Department of Biology, Greensboro, NC 27402 HUANG, S-S. (The Institute of Chinese Medicine of Guangdong province, Guangzhou, 510520, China), J.-P. LIAO (South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou, 510650, China). AND B. K. KIRCHOFF (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Department of Biology, Greensboro, NC 27402), Calcium distribution and function in the glandular trichomes of Lavandula pinnata L. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 137: 1–15. 2010.—Calcium distribution during peltate and capitate glandular trichome development in Lavandula pinnata L. was examined with the potassium antimonate precipitation method. In order to establish a role for calcium in the secretory process and elucidate calcium function in the glands, the effects of calcium removal were investigated by treatment with nifedipine (Nif, a calcium channel blocker) and Ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N9,N9-tetraacetic acid (EGTA, a calcium chelator). Untreated, mature glands accumulate many calcium precipitates in the subcuticular space and adjacent cell wall during secretion. In Nif or EGTA treated plants these precipitates disappear, and the amount of secretory product is drastically reduced. Calcium removal also results in a reduction in gland density, cells with decreased cytoplasmic density, formation of a lax cell wall, abnormal formation of the subcuticular space, thinning of the cuticle, and the presence of multivesicular bodies near the plasma membrane.