Berkeley Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The People's Institute, the National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America

In Defense of the Moving Pictures: The People's Institute, The National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America Nancy J, Rosenbloom Located in the midst of a vibrant and ethnically diverse working-class neighborhood on New York's Lower East Side, the People's Institute had by 1909 earned a reputation as a maverick among community organizations.1 Under the leadership of Charles Sprague Smith, its founder and managing director, the Institute supported a number of political and cultural activities for the immigrant and working classes. Among the projects to which Sprague Smith committed the People's Institute was the National Board of Censorship of Motion Pictures. From its creation in June 1909 two things were unusual about the National Board of Censorship. First, its name to the contrary, the Board opposed growing pressures for legalized censorship; instead it sought the voluntary cooperation of the industry in a plan aimed at improving the quality and quantity of pictures produced. Second, the Board's close affiliation with the People's Institute from 1909 to 1915 was informed by a set of assumptions about the social usefulness of moving pictures that set it apart from many of the ideas dominating American reform. In positioning itself to defend the moving picture industry, the New York- based Board developed a national profile and entered into a close alliance with the newly formed Motion Picture Patents Company. What resulted was a partnership between businessmen and reformers that sought to offset middle-class criticism of the medium. The officers of the Motion Picture Patents Company also hoped 0026-3079/92/3302-O41$1.50/0 41 to increase middle-class patronage of the moving pictures through their support of the National Board. -

FILMS FANTASTIC 11 the Journal of the NFFF Film Bureau

FILMS FANTASTIC 11 The Journal of the NFFF Film Bureau This Issue OUTWARD BOUND Films Fantastic number 11 is published by Eric Jamborsky for the N3F Film Bureau. [email protected] The 1920s are often remembered as The Jazz Age, for Flappers, Sheiks, and Vamps. For genre fans Fritz Lang's METROPOLIS and WOMAN IN THE MOON may come to mind. Then we have the films of Lon Chaney, the Man Of A Thousand Faces, such as PHANTOM OF THE OPERA or the now lost LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT. This was also the decade where Hugo Gernsback published the first magazine devoted to Science Fiction. But there was another side to the decade. Following the unprecedented number of deaths in the First World War, followed by the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919. Of the Flu pandemic, according to the CDC, “The 1918 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Although there is not universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide during 1918-1919. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel in spring 1918. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.” As a result this decade witnessed the growth of Spiritualism and other doctrines by people who had undergone losses during that period. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

Sonya Levien Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf558003r5 No online items Sonya Levien Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson, January 31, 1997, revised November 10, 2010. Initial cataloging and biography Carolyn Powell, November 1994. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Sonya Levien Papers: Finding Aid mssHM 55683-56785, mssHM 74388 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Sonya Levien Papers Dates (inclusive): 1908-1960 Collection Number: mssHM 55683-56785, mssHM 74388 Creator: Levien, Sonya, 1888?-1960. Extent: 1,181 pieces + ephemera and awards in 35 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Hollywood screenwriter Sonya Levien (1888?-1960), including screenplays, literary manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, awards and ephemera. There is also material in the collection related to Levien's early involvement with the Suffrage movement, both in America and England, as well as material recounting life in England and surviving the Blitz in World War Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

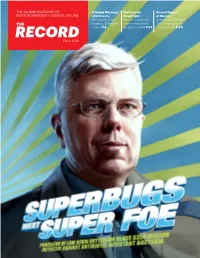

Record Fall 2016 Fall 2016 Inside the Record

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF A Happy Marriage Fighting the Annual Report BOSTON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW of Interests Good Fight of Giving MIT and BU share Four BU Law alumni Building on Excellence: THE Intellectual Property share their passion The Campaign for BU clinics. P.8 for social justice. P.14 School of Law. P.54 RECORD FALL 2016 FALL 2016 INSIDE THE RECORD BU Law The alumni Maureen A. O’Rourke Dean, Professor of Law, receives grant magazine of Michaels Faculty to combat Boston Research Scholar antimicrobial University Oice of Development resistance School of Law & Alumni Relations Lillian Bicchieri, 2 Development Associate Thomas Damiani, Senior Sta A Happy Coordinator Marriage of Terry McManus, 8 Assistant Dean for Interests: Development & BU Law’s IP Alumni Relations Curriculum Oice of Communications & Marketing Ann Comer-Woods, Assistant Dean for Communications & Marketing Lauren Eckenroth, 12 Senior Writer Opportunity in Failure Contributors Rebecca Binder 14 (LAW’06) Patrick L. Kennedy (COM’04) Fighting the Meghan Laska Good Fight: Trevor Persaud (STH’18) Alumni in Indira Priyadarshini Public Service 20 (COM’16) The Right Sara Rimer to Innovate Corinne Steinbrenner (COM’06) Photography Josh Andrus Alex Boerner BU Photography School News John Gillooly & & Updates Professional Event Images, Inc. Max Hirshfeld Tim Llewellyn 22 Chris McIntosh Mark Ostow Photography Melissa Ostrow Class Notes & Jackie Ricciardi Chris Sorensen In Memoriam Michael D. Spencer Dan Watkins Design Ellie Steever, Boston University Creative Services Cover art and Tell us what you illustrations think! Complete our 54 The Red Dress Annual Report Owen Gildersleeves reader survey at of Giving Peter Hoey bit.ly/bulawrecord. -

![[Collection Name]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7478/collection-name-4067478.webp)

[Collection Name]

ZOË AKINS PAPERS 1878 - 1959 FINDING AID The Huntington Library Gayle M. Richardson January 17, 2008 ©The Huntington Library Zoë Akins Papers -- Finding Aid -- page 2 Table of Contents Page Administrative Information 3 Biographical Note 4 Scope and Content Note 5 Container List 6 Manuscripts 6 Correspondence 55 Oversize Correspondence 134 Photographs 135 Drawings 141 Ephemera 142 Oversize Ephemera 151 Indexing: Subjects 151 Indexing: Added Entries 275 Indexing: Form and Genre Terms 298 Bibliography 298 Appendix I: List of Akins’ Works with Original 299 and Alternate Titles Zoë Akins Papers -- Finding Aid -- page 3 Administrative Information The bulk of the collection was acquired from Zoë Akins on March 20, 1952. The following material was acquired separately and added to the collection: Orrick Johns, H.L. Mencken letters to Akins, and H.L. Mencken letter to Jobyna Howland, gift of Zoë Akins, July 28, 1952. Zoë Akins Addenda acquired from the Zoë Akins Estate, May 12, 1961. Zoë Akins manuscripts, “First Verse” and “Iseult, The Fair,” gift of Henry O’Neil. Zoë Akins letter to Alexander Woollcott acquired from Walter R. Benjamin, January 10, 1978, (accession number 493). Zoë Akins typewritten letters (carbon copies), gift of Occidental College Library, January 21, 1982, (accession number 926). Zoë Akins diary, 1924, acquired from R.E. Evans, December 23, 1986, (accession number 1312). The collection has been fully processed and is available for research. The collection numbers 7, 354 cataloged items plus ephemera. Call numbers: ZA 1 - 7330 Restrictions: Willa Cather stated in her will that none of her letters are ever to be published. -

A Study of the Motion Picture Relief Fund's Screen Guild Radio Program 1939-1952. Carol Isaacs Pratt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 A Study of the Motion Picture Relief Fund's Screen Guild Radio Program 1939-1952. Carol Isaacs Pratt Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pratt, Carol Isaacs, "A Study of the Motion Picture Relief Fund's Screen Guild Radio Program 1939-1952." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Cleveland Theatre in the Twenties

This dissertation has been Mic 61-2823 microfilmed exactly as received BROWN, Irving Marsan. CLEVELAND THEATRE IN THE TWENTIES. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Speech - Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CLEVELAND THEATRE IN THE TWENTIES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Irving Marsan Brown, A.B., M.A. *.»**** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of Speech ACKNOWLEDGMENT To lay wife, Eleanor, without whan this would not have been ii CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES........................................ iv Chapter I. INTRO SU C T I O N ............. 1 II. CLEVELAND IN THE TWENTIES....................... U III. THE AMERICAN THEATRE IN THE T W E N T I E S ........... 20 IV. CLEVELAND THEATRE IN THE TWENTIES: INTRODUCTION. U6 V. CLEVELAND THEATRE IN THE TWENTIES: THE COMMERCIAL THEATRE ........................ 71 VI. CLEVELAND THEATRE IN THE TWENTIES: THE AMATEURS ................................. 128 VII. CONCLUSION................................... 20$ BIBLIOGRAPHY............................................ 210 AUTOBIOGRAPHY .......................................... 216 TABLES Table Page 1. Plays That Ran for Over $00 Performances on Broadway Between 1919-20 and 1928-29 . .......... 2$ 2. Road and Stock Company Shows in Cleveland; Statistics: 1919-20 to 1928-29 122 3. Kinds of Shows, 1919-20 and 1928-29 123 U. Play House Productions, 1928-29................ 191 -

ABOUT THIS BOOK Te 2016 – 2017 JBC Network Meet the Author Book Was Prepared by Jewish Book Council for Exclusive Use by JBC Network Members

ABOUT THIS BOOK Te 2016 – 2017 JBC Network Meet the Author book was prepared by Jewish Book Council for exclusive use by JBC Network members. It is intended to assist in the selection of authors and books to feature in book programs hosted by JBC Network member sites for the 2016 – 2017 program year. Te JBC Network is a service provided by the Jewish Book Council, whose mission is to enrich Jewish communities through the literary arts and to encourage and promote the reading, writing, and publishing of books of Jewish interest in the English language. Trough the JBC Network, members become acquainted with writers of newly published books whose works are of specifc interest to JBC Network member organizations. Jewish Book Council does not approve or sanction any of the books or authors herein, but rather provides a platform for their exposure and promotion. Each author in this book (or a representative) has approached Jewish Book Council for the opportunity to introduce their books to sites within the North American Jewish community through the JBC Network. Jewish Book Council will facilitate author visits only upon specifc requests from JBC Network members. An author’s inclusion in this book and/or appearance at the JBC Network Conference Meet the Author event does not guarantee invitations from JBC Network members. Invitation is the sole decision of JBC Network member sites. Te material in this book is organized alphabetically by last name of the author. Te information contained herein has been provided by publishers or authors directly and has been edited but not written by Jewish Book Council. -

Theory, with Special Attention to Moving-Image Materials

/227 Manifestations and Near-Equivalents: Theory, with Special Attention to Moving-Image Materials Martha M. Vee Differences betlceen manifestations and near-equivalents that might be con sidered significant by catalog users are examined. Anglo-Amelican catalog ing practice concerning when to make a new record is examined. Definitions for manifestation, title manifestation, aud near-equivalent are proposed. It is suggested that current practice leads to making too many separate records for near-equivalents. It is recommended that practice be changed so that near-equivalents are more often cataloged on the same record. Next, differ ences between manifestations and near-equivalents of moving-image works are examined, and their Significance to users of moving-image works is assessed. It is suggested that tme manifestations result lchen the continuity, i.e., visual aspect of the work, or the soundtrack, i.e., audio aspect of the work, or the textual aspect ofthe work actually differ, whether due to editing, the appending of new material, or the work ofsubsidiary authors creating subtitles, neu; music tracks, etc. Title manifestations can occur lchen the title or billing order differs lcithout there being any underlying difference in continuity. Distribution infonnation can differ without there being any underlying difference in continuity, creating a near-equivalent. Finally, phYSical variants ornear-equivalents can occur when phYSicalfonnat differs without the involvement ofsubsidiary authors. A manifestation of a work is a version differences that might be considered sig or edition of it that differs Significantly nificant by catalog users, and the ways from another version or edition. A near these differences have been handled by equivalent is used here to mean a copy of Anglo-American cataloging rules. -

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

TO THE MEMBERS OF THE ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES VOL. 3; No. 6-7 9038 MELROSE AVENUE • HOLLYWOOD 46, CALIF. JUNE-JULY, 1947 INTERNATIONAL FILM EXPOSITION PLANNED "IN THE BEGINNING" by HERSHOL T OUTLINES FILM CONGRESS MARY C. MCCALL, JR. IN ADDRESS TO UNITED NATIONS CLUB It is the plan of the Academy to. A film congress, the first of its kind to be held in this country; devote an issue of " For You r In is planned for Hollywood. The exposition, for which no definite formation" to each branch of its date has been set, will include leading artists and craftsmen in the membership until all the Academy motion picture industry the world over. branches have been covered. jean Hersholt, president of the Academy, made the announce . It is appropriate that the first ment before an audience of fifteen hundred members of fifty-five of this series of informational bulle nations at the United Nations Club in Washington. tins should be devoted to the Writ He stated: ers Branch of the Academy. For it "1 feel that at a gathering such as this, it is appropriate that I is as true in the creation of a mo announce that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences tion picture as the Bible tells us it will sponsor an International Film Congress in Hollywood a year was in the creation of the world from this summer. We shall bring together from all parts of the that The Word is the Beginning. world men and woman who made this medium one of the great The story·, the play, is the basis of vehicles for the interchange of social and cultural ideas--probably a motion picture.