The Structure of Municipal Voting in Vancouver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..180 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 15.00)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 146 Ï NUMBER 165 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, October 19, 2012 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 11221 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, October 19, 2012 The House met at 10 a.m. terrorism and because it is an unnecessary and inappropriate infringement on Canadians' civil liberties. New Democrats believe that Bill S-7 violates the most basic civil liberties and human rights, specifically the right to remain silent and the right not to be Prayers imprisoned without first having a fair trial. According to these principles, the power of the state should never be used against an individual to force a person to testify against GOVERNMENT ORDERS himself or herself. However, the Supreme Court recognized the Ï (1005) constitutionality of hearings. We believe that the Criminal Code already contains the necessary provisions for investigating those who [English] are involved in criminal activity and for detaining anyone who may COMBATING TERRORISM ACT present an immediate threat to Canadians. The House resumed from October 17 consideration of the motion We believe that terrorism should not be fought with legislative that Bill S-7, An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Canada measures, but rather with intelligence efforts and appropriate police Evidence Act and the Security of Information Act, be read the action. In that context one must ensure that the intelligence services second time and referred to a committee. and the police forces have the appropriate resources to do their jobs. -

July 29, 2021

SPECIAL COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES JULY 29, 2021 A Special Meeting of the Council of the City of Vancouver was held on Thursday, July 29, 2021, at 1:01 pm, in the Council Chamber, Third Floor, City Hall, for the purpose of convening a meeting which is closed to the public. This Council meeting was convened by electronic means as authorized under the Order of the Minister of Public Safety and Solicitor General of the Province of British Columbia – Emergency Program Act, updated Ministerial Order No. M192. PRESENT: Deputy Mayor Christine Boyle Councillor Rebecca Bligh Councillor Adriane Carr Councillor Melissa De Genova Councillor Lisa Dominato Councillor Pete Fry Councillor Colleen Hardwick Councillor Sarah Kirby-Yung Councillor Jean Swanson Councillor Michael Wiebe ABSENT: Mayor Kennedy Stewart CITY MANAGER’S OFFICE: Paul Mochrie, City Manager Karen Levitt, Deputy City Manager CITY CLERK’S OFFICE: Katrina Leckovic, City Clerk David Yim, Meeting Coordinator WELCOME The Deputy Mayor acknowledged we are on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations and we thank them for having cared for this land and look forward to working with them in partnership as we continue to build this great city together. The Deputy Mayor also recognized the immense contributions of the City of Vancouver’s staff who work hard every day to help make our city an incredible place to live, work, and play. IN CAMERA MEETING MOVED by Councillor De Genova SECONDED by Councillor Wiebe THAT Council will go into meeting later this day which -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

June 4, 2015 Letter from Premier Christy Clark to the Mayor Regarding Housing Affordability, Foreign Investment and Ownership

~YOF · CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information a Privacy File No. : 04-1 000-20-2017-468 March 14, 2018 ?.22(1) Re: Request for Access to Records under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the "Act") I I am responding to your request originally received on November 22, 2017 and then clarified · on December ·7, 2017 for: 1. Any and all subsequent written exchanges between the City .of Vancouver and the Province relating to foreign investment in local real estate from June 1, 2015 to November 21, 2017; City of Vancouver: • the Mayor's Office and Mayor Robertson Province: • The Former Premier Clark • The Current Premier Horgan • Shayne Ramsay of BC Housing • Mike de ~ong , former Minister of Finance • Carole James, current Minister of Finance • Rich Coleman, former Minister of Housing • Ellis Ross, former Minister of Housing • Selina Robinson, current Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing 2. Any and all minutes of meetings, briefing notes or other documents relating to discussions or consultations between the City of Vancouver and the Province regarding housing affordability sihce from June 1, 2015 to November 21 , 2017; and City of Vancouver: • the Mayor's Office and Mayor Robertson Province: • The Former Premier Clark City Hall 453 West 12th Avenue Vancouver BC VSY 1V4 vancouver.ca City Cle rk's Department tel: 604.873.7276 fax: 604.873.7419 • The Current Premier Horgan • Shayne Ramsay of BC Housing • Mike de Jong, former Minister of Finance • Carole James, current Minister of Finance • Rich Coleman, former Minister of Housing • Ellis Ross, former Minister of Housing • Selina Robinson, current Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing 3. -

ACTION PLAN Authorized by Financial Agent Arnedo Lucas (778-558-4098) Copyright 2018 YES Vancouver Party PREFACE

ACTION PLAN Authorized by Financial Agent Arnedo Lucas (778-558-4098) Copyright 2018 YES Vancouver Party PREFACE Over the coming days and weeks, we will be announcing our policies on the many other issues facing our city. Today, we are addressing the most pressing issue: our housing crisis. There are many passionate opinions about the causes and solutions to our housing crisis. They’ve been some of the most contentious Vancouver dinner table discussions for years. However, passionate debates must now make way for compassionate ones. We must accept that there is no you vs. me and only we. We love our city, and we need to say YES to loving our neighbours. We cannot afford to play the politics of division when we have such a crisis before us. We need to stop saying “NO.” Saying “NO” to making room for people in our city has got us into this crisis. YES Vancouver will: • Legalize and build more affordable housing, • Target speculators, not homeowners • Clean up the development and permitting process, and • Build thriving, inclusive neighbourhoods for families. There was a time in my own life where, as a young person, our family lost everything and we became homeless despite working hard and doing the right things. There are many people in the same position today. Over the past ten years, we’ve witnessed a 30% increase in homelessness due to everyday Vancouverites losing their access to decent rental accommodations, and we’ve also seen 9,000 fewer children in our classrooms because families had to flee Vancouver. 3 Many seniors are being forced out of the city they’ve known all their lives because we refuse to legalize anything other than large single-family homes in the neighbourhoods where they could live closer to their children. -

PRESS RELEASE | City of Vancouver

PRESS RELEASE | City of Vancouver Greens, Independents Surge in Vancouver Council Election Methodology: Almost half of residents would like to see several parties Results are based on an represented in City Council. online study conducted from September 4 to Vancouver, BC [September 11, 2018] – As Vancouverites consider September 7, 2018, among their choices in the election to City Council, the parties that 400 adults in the City of Vancouver. The data has traditionally formed the government in the city are not particularly been statistically weighted popular, a new Research Co. poll has found. according to Canadian census figures for age, In the online survey of a representative sample of City of gender and region in the Vancouver residents, 46% say they will “definitely” or “probably” City of Vancouver. The consider voting for Green Party of Vancouver candidates in next margin of error—which month’s election to City Council, while 39% will “definitely” or measures sample “probably” cast ballots for independent candidates. variability—is +/- 4.9 percentage points, nineteen times out of About a third of Vancouverites (32%) would “definitely” or twenty. “probably” consider voting for City Council candidates from the Coalition of Progressive Electors (COPE). The ranking is lower for Would you “definitely” or Vision Vancouver (30%), the Non-Partisan Association (NPA) (also “probably” consider voting 30%), Yes Vancouver (24%), One City (19%), Coalition Vancouver for these parties or (13%), Vancouver First (12%) and ProVancouver (9%). candidates in the election for Vancouver City Council? “The Green Party is definitely outperforming all others in Vancouver when it comes to City Council,” says Mario Canseco, Green Party – 46% President of Research Co. -

Improving Visible-Minority Representation in Local Governments in Metro Vancouver

Electing a Diverse-City: Improving visible-minority representation in local governments in Metro Vancouver by Munir-Khalid Dossa B.A. (Policy Studies), Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 2019 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Public Policy in the School of Public Policy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Munir-Khalid Dossa 2021 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2021 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Munir-Khalid Dossa Degree: Master of Public Policy Thesis title: Electing a Diverse-City: Improving visible- minority representation in local governments in Metro Vancouver Committee: Chair: Dominique Gross Professor, Public Policy Josh Gordon Supervisor Assistant Professor, Public Policy John Richards Examiner Professor, Public Policy ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract Visible minorities make up roughly half of the population in Metro Vancouver. Despite this, their representation in municipal governments is very low, in partial contrast to provincial and federal levels of government, where representation is higher, although still not proportionate. This study documents this underrepresentation at the municipal level, investigates the sources of that underrepresentation and examines policy options to address it. In five case studies, the research looks at the impact of at-large versus ward electoral systems, varying rates of voter turnout, and the influence of incumbency on electoral chances of visible minority candidates. Drawing on these case studies and six subject matter interviews, the study then evaluates four policy options in the Metro Vancouver context: changing to a ward system for elections, education campaigns, civic engagement opportunities and the status quo. -

CVN 2018 Vancouver Election Responses from Candidates

Questions for Vancouver Candidates 2018 The Coalition of Vancouver Neighbourhoods (CVN) asked the candidates for Mayor and Council to each answer four questions of great importance to all Vancouver neighbourhoods. The Questions Trust: What specific actions would you take to increase the public’s trust in Vancouver’s governance? Participation: What specific actions would you take to increase neighbourhood participation in planning changes to their own neighbourhoods? Affordability: What specific actions would you take to increase affordability, retain the city’s most affordable housing, and reduce homelessness in Vancouver? Liveability: What specific actions would you take to enhance liveability in Vancouver? Candidates were strongly encouraged to: • Be brief • Avoid generalities • List as bullet points the specific actions that they would commit to if elected. The Responses Responses to date have been received from some, but not all of the candidates. Candidate responses are listed below in alphabetic order, first for Council, then for Mayor. Responses by Council Candidates Christine Boyle, One City Trust We believe that trust comes from keeping promises and holding fast to values. As elected Councillors, we'll work hard to bring forward policy motions that reflect our policy, connect with and listen to Vancouverites across the city, and maintain our values. Participation We believe that the current consultation process could be improved. We want to work harder to reach people in their communities, and talk to all residents, not just those who are able to show up to a public hearing and speak publicly. We believe that access to the planning process could be improved through increased access to translation services, training for planners to work across cultures, and improving rates of participation for families with young children and people with disabilities. -

The Role of Local Political Parties on Rezoning Decisions in Vancouver (1999-2005)

Do Political Parties Matter at the Local Level? The Role of Local Political Parties on Rezoning Decisions in Vancouver (1999-2005) Edna Cho Bachelor of Arts, University of Calgary, 1997 PROJECT SUBMl7TED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF URBAN STUDIES In the Urban Studies Program O Edna Cho, 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2007 All rights resewed. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Edna Cho Degree: Master of Urban Studies Title of Research Project: Do Political Parties Matter at the Local Level? The Role of Local Political Parties on Rezoning Decisions in Vancouver (I999-2005) Examining Committee: Chair Dr. Len Evenden Dr. Patrick Smith Professor, Department of Political Science Simon Fraser University Vancouver, British Columbia Senior Supervisor Dr. Anthony Perl Professor and Director, Urban Studies Program Simon Fraser University Vancouver, British Columbia Supervisor Dr. Kennedy Stewart Assistant Professor, Public Policy Program Simon Fraser University Vancouver, British Columbia External Examiner Date Defended 1 Approved: I 0 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY~ibra ry DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

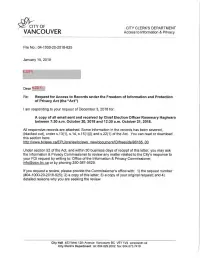

VANCOUVER Access to Information & Privacy

~YOF CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information & Privacy File No.: 04-1000-20-2018-625 January 15, 2019 s.22(1) Dear s2 2TfJ Re: Request for Access to Records under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the "Act") I am responding to your request of December 3, 2018 for: A copy of all email sent and received by Chief Election Officer Rosemary Hagiwara between 7:30 a.m. October 20, 2018 and 12:30 a.m. October 21, 2018. All responsive records are attached. Some information in the records has been severed, (blacked out), under s.13(1), s.1 4, s.15(1)(I) and s.22(1) of the Act. You can read or download this section here: http://www.bclaws.ca/EPLibraries/bclaws new/document/I D/freeside/96165 00 Under section 52 of the Act, and within 30 business days of receipt of this letter, you may ask the Information & Privacy Commissioner to· review any matter related to the City's response to your FOi request by writing to: Office of the Information & Privacy Commissioner, [email protected] or by phoning 250-387-5629. If you request a review, please provide the Commissioner's office with: 1) the request number (#04-1000-20-2018-625); 2) a copy of this letter; 3) a copy of your original request; and 4) detailed reasons why you are seeking the review. City Hall 453 West 12th Avenue Vancouver BC V5Y 1V4 vancouver.ca City Clerk's Department tel: 604.829.2002 fax: 604.873.7419 Yours truly, Barbara~ J. -

Vision Vancouver

~TYOF CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMEI VANCOUVER Election Office ELECTOR ORGANIZATION CAMPAIGN FINANCING DISCLOSURE STATEMENT IN THE 2011 GENERAL LOCAL ELECTION Vancouver Charter, Division 8 [Campaign Financing] NOTE: This document will be made available to the public as follows: • It may be inspected in the City Clerk's Office during regular office hours [Section 65(1) of the Vancouver Charter] • It will be posted on the City of Vancouver web site [City Council resolution, May 13, 2008] The deadline for filing this disclosure statement is Monday. March 19. 2012 VISION VANCOUVER ELECTOR ASSOCIATION NAME OF ELECTOR ORGANIZATION See attached Schedule "Candidates 2011" NAME(S) OF ENDORSED CANDIDATE(S) AND OFFICE~OR WHICH THE CANDIDATE(S) SOUGHT ELECTION* * If you are attaching a list, check this box: ~ SUMMARY OF CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS Total amount of campaign contributions (Total from Part 1 of Schedule A): $ 2,227,402.34 (Note: Part 2 of Schedule Acontains a list of contributors who have contributed $100 or more) Total amount of anonymous campaign contributions remitted o to the City of Vancouver (Total from Part 3 of Schedule A): $----- SUMMARY OF ELECTION EXPENSES Total amount of election expenses (Total from Schedule B): $ 2,218,040.20 SURPLUS FUNDS $__0__ Transfer from City of Vancouver (surplus funds from previous election): Balance (positive or negative) remaining in Elector Organization's campaign account (Total from Line "A" in Schedule C): $ 9,362.14 CAMPAIGN ACCOUNT INFORMATION All campaign contributions of money were deposited in, and all election expenses were paid from, one or more campaign accounts opened for this purpose at: VANCITV located at. -

NEWS-CLIPS Oct 19/2018 to Nov 21/2018

NEWS-CLIPS Oct 19/2018 to Nov 21/2018 New Seymour River suspension bridge nearly finished.pdf 66 year old bridge bound for replacement.pdf Nobody home.pdf A look at the election results.pdf North Shore a leader for homes built with the BC Energy Step Code.pdf Addiction recovery facility opens for men in North Van.pdf North Van students learn waterway restoration.pdf BC have a choice of 3 good PR systems.pdf North Vancouver Election Results.pdf BC proportional representation vote is dishonest.pdf North Vancouver hostel owner found in contempt of court.pdf Bridge to the future.pdf North Vancouver residents warned of water testing scam.pdf Capilano Substation.pdf North Vancouver student vote mirrors adult choice.pdf Change of office.pdf Notice - Early Input Opportunity.pdf Climate change activist spamming politicians for a better tomorrow.pdf Notice -PIM for a Heritage Revialization Agreement .pdf Consider the cost before you vote for electoral reform.pdf Notice-PIM-for-1510-1530 Crown Str.pdf Developers furious with City of White Rock as council freezes tower plans.pdf Old grey mayors - the story of NV early leaders -part 1.pdf Dog ban part of long-rang plan for Grouse Mountain park.pdf Old grey mayors - the story of NV early leaders -part 2.pdf Dont like density - you aint seen nothin yet.pdf Old grey mayors-part2.pdf Drop in anytime.pdf Outgoing City of North Van council entitled to payouts.pdf Electoral reform not that complicated.pdf Pot pipe in car earns driver ticket in West Van.pdf ELECTORAL REFORM PUSH ABOUT POWER -IDEOLOGY.pdf