Through the Looking Glass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandatory Data Retention by the Backdoor

statewatch monitoring the state and civil liberties in the UK and Europe vol 12 no 6 November-December 2002 Mandatory data retention by the backdoor EU: The majority of member states are adopting mandatory data retention and favour an EU-wide measure UK: Telecommunications surveillance has more than doubled under the Labour government A special analysis on the surveillance of telecommunications by states have, or are planning to, introduce mandatory data Statewatch shows that: i) the authorised surveillance in England, retention (only two member states appear to be resisting this Wales and Scotland has more than doubled since the Labour move). In due course it can be expected that a "harmonising" EU government came to power in 1997; ii) mandatory data retention measure will follow. is so far being introduced at national level in 9 out of 15 EU members states and 10 out of 15 favour a binding EU Framework Terrorism pretext for mandatory data retention Decision; iii) the introduction in the EU of the mandatory Mandatory data retention had been demanded by EU law retention of telecommunications data (ie: keeping details of all enforcement agencies and discussed in the EU working parties phone-calls, mobile phone calls and location, faxes, e-mails and and international fora for several years prior to 11 September internet usage of the whole population of Europe for at least 12 2000. On 20 September 2001 the EU Justice and Home Affairs months) is intended to combat crime in general. Council put it to the top of the agenda as one of the measures to combat terrorism. -

Excerpt from GOD's BANKERS by Gerald Posner 1 Murder in London

Excerpt from GOD’S BANKERS by Gerald Posner 1 Murder in London London, June 18, 1982, 7:30 a.m. Anthony Huntley, a young postal clerk at the Daily Express, was walking to work along the footpath under Blackfriars Bridge. His daily commute had become so routine that he paid little attention to the bridge’s distinctive pale blue and white wrought iron arches. But a yellowish orange rope tied to a pipe at the far end of the north arch caught his attention. Curious, he leaned over the parapet and froze. A body hung from the rope, a thick knot tied around its neck. The dead man’s eyes were partially open. The river lapped at his feet. Huntley rubbed his eyes in disbelief and then walked to a nearby terrace with an unobstructed view over the Thames: he wanted to confirm what he had seen. The shock of his grisly discovery sank in.1 By the time Huntley made his way to his newspaper office, he was pale and felt ill. He was so distressed that a colleague had to make the emergency call to Scotland Yard.2 In thirty minutes the Thames River Police anchored one of their boats beneath Blackfriars’ Number One arch. There they got a close-up of the dead man. He appeared to be about sixty, average height, slightly overweight, and his receding hair was dyed jet black. His expensive gray suit was lumpy and distorted. After cutting him down, they laid the body on the boat deck. It was then they discovered the reason his suit was so misshapen. -

La-Banda-Della-Magliana.Pdf

INDICE 1. La Banda della Magliana.................................................................................................................... 2. La struttura criminale della Banda della Magliana............................................................................. 3. Banda della Magliana......................................................................................................................... 4. Una Banda tra mafia, camorra e servizi segreti.................................................................................. 5. I rapporti tra la Banda della Magliana e Licio Gelli........................................................................... 6. I ricatti della Banda............................................................................................................................ 7. Gli intrecci pericolosi della Banda della Magliana............................................................................ 8. Dall’assassinio di Carmine Pecorelli alla fuga di Calvi..................................................................... 9. La mala romana e la Mafia................................................................................................................. 10. Vita e morte della gang romana........................................................................................................ 11. Banda della Magliana: i padroni di Roma........................................................................................ 12. Omicidio di Roberto Calvi.............................................................................................................. -

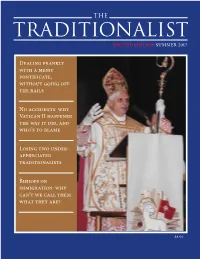

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

The Devil's Banker

THE DEVIL'S BANKER Screenplay by Gary Van Haas Based on the Novel by Gary Van Haas June 2017 Draft WGAw Registration #1346965 (c) 2014 by Gary Van Haas CINEMA ARTS GROUP [email protected] INSERT: "BASED ON ACTUAL EVENTS" FADE IN: EXT. DOCKSIDE WAREHOUSE - DAY A series of shipping containers stacked across from the front of a warehouse with the garage-style door open. Policeman SERGE PORTER (late 30’s) and his partner P.C. PAULA SANTOLI (29), hide belly down on top of a crate. They peer down at TWO THUGS leaning against a stack of palettes facing away from the cop's hiding spot. Porter moves ahead first, then Paula, getting the drop on the two men and... Porter pulls out his pistol and jumps down from the crate yelling as he RUNS for the THUGS with his pistol out. Paula follows as the THUGS whirl in surprise, hands shooting into the air. They drop to the ground, hands behind their heads as Porter covers them with his weapon. Just as they are about to cuff them...Paula smiles at Porter and takes THUG #1's hand as... A CAR revs up and tears out of the warehouse. A MAN jumps out... The MUZZLE flash of AN UZI lights up the darkness of the WAREHOUSE ENTRANCE as a car driven by THUG #3 roars toward them. ON PORTER: He sees the man then hears staccato GUN SHOTS - an UZI blazing away at them! He dives behind a palette...gets off a couple of rounds. Then, with a yell to Paula, as he dives behind the palettes. -

The Denver Catholic Register World Awaits the White Smoke

THE DENVER CATHOLIC REGISTER. Wed.. Auauel 3.T ISTB ---- i e The Denver Catholic Register WEDNESDAY, AUGUST23, 1978 VOL. LIV NO. 1 Colorado's Largest Weekly 20 PAGES 25 CENTS PER COPY a ! i \ v^. THE HOLY SPIRIT MOVES IN OQ THE CONCLAVE O y-h World Awaits the White Smoke By John Muthig where their peers stand on key issues and what they Papal election rules say that cells must be chosen VATICAN CITY (NC) — As hundreds of the have been up to in their own regions. by lot. curious stream past Pope Paul’s simple tomb below St. Peter's, the College of Cardinals has already U.S. Cardinals Absolute Secrecy unofficially begun electing his successor. All eight U.S. cardinals who will enter the All cardinals are sworn to absolute secrecy, not The commandant of the Swiss Guards and a small conclave —• U.S. Cardinal John Wright, prefect of the only about what goes on in the conclave but also about group of Vatican officials will not seal the oak Vatican Congregation for the Clergy, officially the general congregations. conclave doors officially until 5 p.m. Aug. 25, but the informed fellow cardinals by telegram Aug. 14 that he Each had to take the following oath in the presence cardinals during their daily meetings in baroque, cannot attend for health reasons — are participating of his fellow cardinals: frescoed halls near the basilica have already begun the daily in the meetings (called general congregations) of “We cardinals of the Holy Roman Church ... key process of getting to know one another and sizing the college. -

A Map of the Financial Powers That Control P-2 Operations

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 8, Number 27, July 7, 1981 THE BANKING CONNECTIONS A map of the financial powers that control P-2 operations by David Goldman, Economics Editor Italian banking has been more international in character precedented opportunity to work through the Chinese than any other country's since the 14th century, and it is boxes of money-laundering fr om the inside outwards. not likely that a scandal implicating the board chairmen The most prominent financier of the Italian Socialist of every major Italian bank could fail to have worldwide Party, Calvi built the $6 billion Banco Ambrosiano as the ramifications. In fact, the publication of P-2 Grand core of a $20 billion international empire of merged and Master Licio Gelli's membership list sent shock waves associated companies. But Ambrosiano itself fits tightly out to Canada, Hong Kong, and the Caribbean. The into a larger series of boxes, a publicity-shy but powerful evidence now in the public domain comes very close to international syndicate known as "Inter-Alpha," among demonstrating the existence of a tightly coordinated the first. It includes West Germany's BHF-Bank, world network for dirty money transactions-a "Dope, France's Swiss-connected Credit Commercial, the Kre Inc.," as this publication first characterized it in an dietbank of Luxemburg, and the British combination of October 1978 feature. Williams and Glyns-Royal Bank of Scotland, the latter Not merely the major Italian banks, but Bank of about to merge with the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank. America and Chase Manhattan in the United States, the Ambrosiano is thoroughly Italian in character, but Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, and major institutions not in ownership. -

The Catholic Church in the Czech Lands During the Nazi

STUDIA HUMANITATIS JOURNAL, 2021, 1 (1), pp. 192-208 ISSN: 2792-3967 DOI: https://doi.org/10.53701/shj.v1i1.22 Artículo / Article THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE CZECH LANDS DURING THE NAZI OCCUPATION IN 1939–1945 AND AFTER1 LA IGLESIA CATÓLICA EN LOS TERRITORIOS CHECOS DURANTE LA OCUPACIÓN NAZI ENTRE LOS AÑOS 1939–1945 Y DESPUÉS Marek Smid Charles University, Czech Republic ORCID: 0000-0001-8613-8673 [email protected] | Abstract | This study addresses the religious persecution in the Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia) during World War II, when these territories were part of the Bohemian and Moravian Protectorate being occupied by Nazi Germany. Its aim is to demonstrate how the Catholic Church, its hierarchy and its priests acted as relevant patriots who did not hesitate to stand up to the occupying forces and express their rejection of their procedures. Both the domestic Catholic camp and the ties abroad towards the Holy See and its representation will be analysed. There will also be presented the personalities of priests, who became the victims of the Nazi rampage in the Czech lands at the end of the study. The basic method consists of a descriptive analysis that takes into account the comparative approach of the spiritual life before and after the occupation. Furthermore, the analytical-synthetic method will be used, combined with the subsequent interpretation of the findings. An additional method, not always easy to apply, is hermeneutics, i.e., the interpretation of socio-historical phenomena in an effort to reveal the uniqueness of the analysed texts and sources and emphasize their singularity in the cultural and spiritual development of Czech Church history in the first half of the 20th century. -

Banda Della Magliana Vi: L'impero Economico Di De Pedis

BANDA DELLA MAGLIANA VI: L'IMPERO ECONOMICO DI DE PEDIS di Angelo Barraco 23 giugno 1986, a quasi 3 anni dalla prima deposizione di Lucioli, la Corte D’Assise condanna in primo grado 37 imputati su 60. La sentenza riconosce principalmente il traffico di stupefacenti, la metà di loro tornano liberi, compreso Enrico De Pedis. La condanna più pedante va ad Edoardo Toscano, dovrà scontare 20 anni di carcere per omicidio. La battaglia con la giustizia è stata vinta ma una nuova minaccia arriva da un affiliato che fino a quel momento aveva agito nell’ombra, si chiama Claudio Sicilia detto “il vesuviano”. Claudio Sicilia è tra i pochissimi scampati all’arresto del 1983, con i compagni in carcere ha preso le redini dell’organizzazione. La sua reggenza finisce nell’autunno del 1986, anno in cui viene arrestato. Temendo per la sua incolumità, Sicilia decide di parlare e conferma i racconti degli altri pentiti e aggrava le posizioni degli altri compagni. Lui parla delle finte malattie di Abbatino. Abbatino vuole riprendere il controllo dell’organizzazione cercando l’appoggio negli amici di sempre, ma viene ignorato. Ha capito che ha Roma non ha più alleati ma nemici. Il 23 dicembre del 1986 Abbatino, che era ricoverato a Villa Gina da molti mesi, evade dalla villa tramite il supporto di lenzuola. Si da alla latitanza e fa perdere le sue tracce, a regnare sulla capitale adesso c’è soltanto De Pedis. 17 marzo 1987, pochi mesi dopo l’evasione di Abbatino, la procura di Roma emette 91 ordini di cattura contro le persone chiamate in causa da Claudio Sicilia. -

Jeff Katz Obituary Michael Gillard Thu 21 Jan 2021 21.50 GMT

Crime Jeff Katz obituary Michael Gillard Thu 21 Jan 2021 21.50 GMT Corporate investigator who rejected dubious tactics and agents to shine a light on foul play Jeff Katz was working as a journalist when he was invited to join Kroll Associates, then rose to be head of its European operations Jeff Katz, who has died aged 74 from a heart attack, played a key role in changes to the corporate investigation business, first at Kroll Associates, then at Bishop International. Long before the Leveson inquiry, and as far back as the early 1970s, there have been prosecutions in the UK for phone hacking and blagging of information involving small-time private investigators, some of them working on behalf of the press, and colourful cases of industrial espionage in the US involving so-called “dumpster diving” by PIs acting for corporate clients. As a former journalist Katz was well aware of this history and looked to move away from such dubious tactics and players. He was an advocate of government regulation of the £250m-a-year business that has emerged in Britain over the past four decades. Rather than the world-weary private eyes of film and literature, corporate investigation involves expensive organisations dominated by lawyers, accountants, former MI6/MI5 agents and retired senior police or military officers. They prefer to be known as business intelligence providers, strategic advisers and risk or security consultants, relying on public record and legally obtained information. Katz’s highest-profile case was a two- year Kroll investigation that he led into the death in London of the Italian banker Roberto Calvi, which undermined the official version that Calvi had hanged himself beneath Blackfriars Bridge in 1982. -

How Propaganda-2 Operates Within South America

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 8, Number 28, July 21, 1981 How Propaganda-2 opera�es within South America by Mark Sonnenblick For the past month, Italian Interpol officials have be P.2 grand master Licio Gelli keeps his Italian wife seeched the cooperation of their Uruguayan and Para and son in a $5 million Montevideo mansion, amidst a guayan counterparts in capturing the grand master of neighborhood of aristocratic properties that he owns. the Propaganda 2 Masonic lodge, Licio Gelli. Gelli and According to the local daily EI Dia. Gelli fills a down his banker partner Umberto Ortolani are wanted in Italy town Montevideo office building with the assorted dum for their leadership of a conspiracy to assassinate politi my corporations through which he helps manage P-2 cal leaders, spread terror, and organize a military coup dirty-money flows. to return Italy to the grip of the Savoy monarchy and its unreconstructed fascist allies. 'Alive and well in Argentina' For the very reason that Italian authorities were Gelli is no novice in this business. At the end of probably searching in the right place for these respect World War II, he worked with the Italian-Swiss banks able managers of an underworld empire, their efforts to move the ill-begotten family fortunes of escaped I have proved fruitless. The P-2 lodge and the ancient Fascists and Nazis to their havens, "alive and well," in family fortunes that are the main beneficiaries of its Argentina. activities have already seized power in the Southern Cone The Italian Fascists, their hoards, and their compa of Latin America. -

Banco Ambrosiano

Banco Ambrosiano In a great bookGreat “ Financial Scandals”, the author, Sam Jaffa, writes on the collapse of Banco Ambrosiano in 1982, which rocked the financial world. “The Banco Ambrosiano collapsed in 1982 with debts of more than $1.3 billion, and in June of that year its Chairman, Roberto Calvi, was found dead in rather macabre circumstances, hanging beneath < ?xml:namespace prefix = st1 ns = "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:smarttags" />London‘s Blackfriars Bridge. His demise has never been fully explained – was it suicide or murder? What would become clear, however, was that the VaticanBank – the Istituto per le Opere di Religione (IOR) – which was a shareholder in Banco Ambrosiano, was to lose heavily when the latter collapsed. The Vatican made a ‘voluntary’ contribution to creditors of Banco Ambrosiano amounting to $244 million, and altogether the scandal probably cost it a further $160 million in losses. However, the extent of the Vatican’s dealings have never fully come to light, because Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, the American who headed IOR from 1971 until his retirement in 1990, was deemed to be outside the jurisdiction of the Italian courts. In February 1987 a Milan court issued a warrant for his arrest and that of two of his associates, Luigi Mennini and Pellegrino de Strobel, on charges of fraudulent bankruptcy (which carried a penalty of up to fifteen years in prison). With this hanging over his head, the Archbishop was for a time confined to his state rooms in the Vatican, which was tough for the sports-loving cleric, who particularly enjoyed a round of golf.