The Disproportionate Appeal of Frank Bridge's Music To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: a Study of Traditions and Influences

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2012 Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences Sara Gardner Birnbaum University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Birnbaum, Sara Gardner, "Elegies for Cello and Piano by Bridge, Britten and Delius: A Study of Traditions and Influences" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 102 Viola V30 N2 Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 1

Viola V30 N2_Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 101 30 Years of JAVS Features: A Survey of Hans Gál’s Chamber Works Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part I Alfred Uhl’s Viola Études Primrose’s Transcriptions Volume 30 Volume Number 2 and Arrangements Journal of Journal the American Viola Society Viola V30 N2_Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 102 Viola V30 N2_Viola V26 N1 11/7/14 6:25 PM Page 1 Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Fall 2014 Volume 30 Number 2 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: Announcements ~ In memoriam Feature Articles p. 13 A Survey of Hans Gál’s Chamber Works with Viola: Richard Marcus writes on the Austrian composer Hans Gál, who emigrated to Great Britain due to World War II. A catalog of his chamber works with viola is provided, along with a look at various selections of these compositions. p. 27 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part I: In the first installment of a two-part article, Elena Artamonova provides a detailed historical context of the Russian violist Vadim Borisovsky—who, in addition to his musical accomplishments, was also a poet. p. 37 Alfred Uhl’s Viola Études: Studies with a Heart: Études have long been an indispensible part of a violist’s training, but have also been typically confined to providing technical facility. Danny Keasler looks at the études of Alfred Uhl, which include melodic aspects that can relate directly to repertoire. -

Past Commissions 2014/15

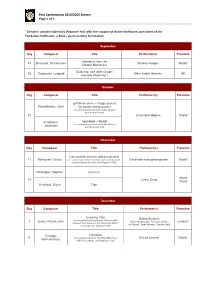

Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 1 of 5 * Denotes commissioned by Wigmore Hall with the support of André Hoffmann, president of the Fondation Hoffmann, a Swiss grant-making foundation September Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Variations from the 14 Birtwistle, Sir Harrison Nicolas Hodges World* Golden Mountains Study No. 44A after Chopin 15 Godowsky, Leopold Marc-André Hamelin UK nouvelle étude No.1 October Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première gefährlich dünn — fragile pieces Petraškevičs, Jānis for double string quartet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern and Wigmore Hall) 10 Ensemble Modern World* Schöllhorn, sous-bois – Sextet (co-commissioned by Ensemble Modern Johannes and Wigmore Hall) November Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Carnaval for clarinet, piano and cello 11 Mantovani, Bruno (co-commissioned by Ensemble intercontemporain, Ensemble intercontemporain World* Opéra national de Paris and Wigmore Hall) Montague, Stephen nun-mul World 16 Jenna Sung World Pritchard, Gwyn Tide December Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Uncanny Vale Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 3 Jones, Patrick John (Emer McDonough, Nicholas Daniel, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted Joy Farrall, Sarah Burnett, Stephen Bell) campaign and Wigmore Hall) Turnage, Contusion 6 (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, Belcea Quartet World* Mark-Anthony NMC Recordings and Wigmore Hall) Past Commissions 2014/2015 Season Page 2 of 5 January Day Composer Title Performer(s) Première Light and Matter Britten Sinfonia (co-commissioned by Britten Sinfonia with 14 Saariaho, Kaija (Jacqueline Shave, Caroline Dearnley, London* support from donors to the Musically Gifted campaign Huw Watkins) and Wigmore Hall) 3rd Quartet Holt, Simon (co-commissioned by The Radcliffe Trust, World* NMC Recordings, Heidelberger Frühling, and 19 Wigmore Hall) JACK Quartet Haas, Georg Friedrich String Quartet No. -

Mariastangier

HIGH DEFINITION ORGAN ROLAND MARIA STANGIER English Town Hall Organ Philharmonie Duisburg Holst • Händel • Vierne Elgar • Bridge • Franck Gárdonyi Von Roland Maria Stangier ROLAND MARIA mit Astrologie. Das siebensätzige Werk ist aus for- STANGIER maler und harmonischer Sicht sowie in der berau- English Town Hall Organ Philharmonie Duisburg schend-virtuos gehaltenen üppigen Instrumenta- Gustav Holst tion ungemein originell. Sieben Planeten (Mars, Holst • Händel • Vierne • Elgar • Bridge • Franck • Gárdonyi „Jupiter“ aus op. 32 Venus, Merkur, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus und Nep- tun) werden ganz subjektiv, individuell „beleuch- „Als Hauptziel sollte angestrebt werden, für Orgel tet“, „beschrieben“: „In jüngster Zeit hat der Cha- arrangierte Musik so zum Klingen zu bringen, als rakter jedes einzelnen Planeten enorm viel in mir Gustav Holst (1874–1934) | arr.: Roland Maria Stangier (*1957) Roland Maria Stangier (*1957) wäre sie original für Orgel geschrieben worden“, angeregt, und ich habe mich ziemlich eingehend 1 „Jupiter“ aus op. 32 8:23 Improvisationen schreibt Herbert Ellingford 1922 in „The Art of mit Astrologie beschäftigt“ schrieb er 1913. (1685-1759) | arr.: Henry Smart (1813-1879) 9 I „Strings“ (Streicher) 3:13 Georg Friedrich Händel Transcribing for the Organ“. Dem ist nichts hinzu- 2 „Konzert für Orgel und Orchester“ op. 4 Nr. 5 9:10 10 II „Diapasons“ (Prinzipale) 2:06 zufügen. Entsprechend sind die vielfältigen Tran- So ist hier Jupiter der Bote jubilierender Freude 11 III „Flutes“ (Flöten) 2:08 Louis Vierne (1870-1937) skriptionen von Symphonien, Chorwerken oder und nicht gestrenger Herr des Olymp und Blitz 12 IV „Reeds“ (Zungen) 3:02 3 „Claire de lune“ aus op. 53 9:05 Kammermusik zwischen 1870 und 1930 zahl- und Donner schleudernd. -

London Mozart Players Wind Trio When He Left to Focus on His Freelance Career

Timothy Lines (Clarinet) Timothy studied at the Royal College of Music with Michael Collins and now enjoys a wide- ranging career as a clarinettist. He has played with all the major symphony orchestras in London as well as with chamber groups including London Sinfonietta and the Nash Ensemble. From 1999 to 2003 he was Principal Clarinet of the London Symphony Orchestra and was also chairman of the orchestra during his last year there. From September 2004 to January 2006 he was section leader clarinet of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, London Mozart Players Wind Trio when he left to focus on his freelance career. He plays on original instruments with the English Baroque Soloists, the Orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique and the Orchestra of Thursday 12th March 2020 at 7.30 pm the Age of Enlightenment and is also frequently engaged to record film music and pop music Cavendish Hall, Edensor tracks. Timothy is Professor of Clarinet at both the Royal College of Music and the Royal Academy of Music, and is the clarinet coach for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. In March 2016 he was awarded a Fellowship of the Royal College of Music and was later that year invited to become Principal Clarinet of the London Mozart Players. Concert Champêtre H. TOMASI Gareth Hulse (Oboe) (1901-1971) After reading music at Cambridge, Gareth Hulse studied with Janet Craxton at the Royal Divertimento K439b W.A. MOZART Academy of Music, and with Heinz Holliger at the Freiburg Hochschule fur Musik. On his (1756-1791) return to England he was appointed Principal Oboe with the Northern Sinfonia, a position he has since held with English National Opera and the London Philharmonic. -

Six Folk Songs from Norfolk

1 Six folk songs from norfolk Voice & Piano by E.J. Moeran VOCAL SCORE 2 This score is in the Public Domain and has No Copyright under United States law. Anyone is welcome to make use of it for any purpose. Decorative images on this score are also in the Public Domain and have No Copyright under United States law. No determination was made as to the copyright status of these materials under the copyright laws of other countries. They may not be in the Public Domain under the laws of other countries. EHMS makes no warranties about the materials and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You may need to obtain other permissions for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy or moral rights may limit how you may use the material. You are responsible for your own use. http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/ Text written for this score, including project information and descriptions of individual works does have a new copyright, but is shared for public reuse under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 International) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Cover Image: ”Peace (detail)” by Benjamin Williams Leader, 1915 3 The “renaissance” in English music is generally agreed to have started in the late Victorian period, beginning roughly in 1880. Public demand for major works in support of the annual choral festivals held throughout England at that time was considerable which led to the creation of many large scale works for orchestra with soloists and chorus. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain. -

Fundamental Techniques in Viola Spaces of Garth Knox. (2016) Directed by Dr

ÉRTZ, SIMON ISTVÁN, D.M.A. Beyond Extended Techniques: Fundamental Techniques in Viola Spaces of Garth Knox. (2016) Directed by Dr. Scott Rawls. 49 pp. Viola Spaces are often seen as interesting extra projects rather than valuable pedagogical tool that can be used to fill where other material falls short. These works can fill various gaps in the violist’s literature, both as pedagogical and performance works. Each of these works makes a valuable addition to the violist’s contemporary performance repertoire as a short, imaginative, and musically satisfying work and can be performed either individually or as part of a smaller set in a larger program (see Appendix A). They all also present interesting technical challenges that explore what are seen as extended techniques but can also be traced back to work on some of the fundamentals of viola technique. Etudes for viola are often limited to violin transcriptions mostly written in the eighteenth, nineteenth, or early twentieth centuries. Contemporary etudes written specifically for viola are valuable but are usually not as comprehensive or as suitable for performance etudes as are Viola Spaces. Few performance etudes cover the technical varieties that are presented in these works of Garth Knox. In this paper I will discuss the historical background of the viola and etudes written for viola. Many viola etudes written in the earlier history of the viola have not continued to be published; this study will also look at why some survived and others are no longer used. Compared to literature for the violin there are large gaps in the violists’ repertoire that Viola Spaces does much to fill; furthermore many violinists have asked for transcriptions of these works. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

103 CHAPTER V STRING SEXTET, OP. 47 in the Standard

CHAPTER V STRING SEXTET, OP. 47 In the standard instrumentation of two violins, two violas, and two cellos, only a half-dozen works for string sextet, all from the Romantic tradition, enjoy a place in the standard repertoire today. These are: the two sextets of Johannes Brahms, op. 18 in B f and op. 36 in G; Dvorak’s Sextet in A, op. 48; and the program works of the Romantic era, Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, Tchaikowsky’s Souvenir di Florence, and Richard Strauss’s Prelude to Capriccio. The efforts by Vincent d’Indy and Joseph Joachim Raff, as well as a handful of their lesser-known contemporaries, have fallen into obscurity. In the post-Romantic era, contributions to the genre have come from Frank Bridge, Erich Korngold, Bohuslav Martinu˚, Darius Milhaud, Walter Piston, Quincy Porter, and Max Reger, along with a few dozen works from lesser-known composers.1 Part of the reason for this sparsity of repertoire can be attributed to the overwhelming popularity of the string quartet, which since Haydn’s time has been the accepted proving ground for composers of chamber music. Another factor, in the post- 1 Margaret K. Farish, String Music in Print, 2nd ed. (New York, R.R. Bowker & Co, 1973), 289–90; 1984 Supplement (Philadelphia: Musicdata, Inc., 1984), 99–101; 1998 Supplement (Philadelphia: Musicdata, Inc.), 101–4. This periodically updated catalog offers the most complete listing of string chamber music available in the last thirty years. 103 104 tonal era, is the exploration of new and atypical sound combinations, which has led to a great proliferation of untraditional mixed ensembles, including acoustic and electronic instruments. -

November 2016

November 2016 Igor Levit INSIDE: Borodin Quartet Le Concert d’Astrée & Emmanuelle Haïm Imogen Cooper Iestyn Davies & Thomas Dunford Emerson String Quartet Ensemble Modern Brigitte Fassbaender Masterclasses Kalichstein/Laredo/ Robinson Trio Dorothea Röschmann Sir András Schiff and many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–X Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – X AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats.