Petition for Rehearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korn MP3 Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Korn MP3 Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: MP3 Collection Country: Russia Style: Alternative Rock, Hardcore, Nu Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1479 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1820 mb WMA version RAR size: 1182 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 701 Other Formats: MP1 MMF AU RA FLAC AIFF MPC Tracklist Hide Credits 1994 - Korn 1 –Korn Blind 0:47 2 –Korn Ball Tongue 4:29 3 –Korn Need To 4:01 4 –Korn Clown 4:37 5 –Korn Divine 2:51 6 –Korn Faget 5:49 7 –Korn Shoots And Ladders 5:22 8 –Korn Predictable 4:32 9 –Korn Fake 4:51 10 –Korn Lies 3:22 11 –Korn Helmet In The Bush 4:02 Daddy 12A –Korn 17:31 Voice – Judith Kiener 12B –Korn Michael And Geri 1996 - Life Is Peachy 13 –Korn Twist 0:49 14 –Korn Chi 3:54 15 –Korn Lost 2:55 16 –Korn Swallow 3:38 17 –Korn Porno Creep 2:01 18 –Korn Good God 3:20 Mr. Rogers 19 –Korn 5:10 Guitar [Additional] – Jonathan Davis 20 –Korn K@#0%! 3:02 21 –Korn No Place To Hide 3:31 Wicked 22 –Korn 4:00 Vocals – Chino MorenoWritten-By – Ice Cube A.D.I.D.A.S. 23 –Korn 2:32 Vocals [Additional] – Baby Nathan Low Rider 24 –Korn 0:58 Cowbell – Chuck Johnson Written-By – War 25 –Korn Ass Itch 3:39 Kill You 26A –Korn 8:37 Guitar [Additional] – Jonathan Davis 26B –Korn Twist (A Capella) 1998 - Follow The Leader 27 –Korn It's On! 4:28 28 –Korn Freak On A Leash 4:15 29 –Korn Got The Life 3:45 30 –Korn Dead Bodies Everywhere 4:44 Children Of The Korn 31 –Korn 3:52 Featuring – Ice Cube 32 –Korn B.B.K 3:56 33 –Korn Pretty 4:12 All In The Family 34 –Korn 4:48 Featuring – Fred Durst 35 –Korn Reclaim My Place 4:32 -

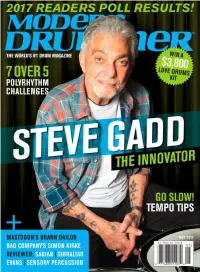

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Leon Bridges Black Moth Super Rainbow Melvins

POST MALONE ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER LORD HURON MELVINS LEON BRIDGES BEERBONGS & BENTLEYS REBOUND VIDE NOIR PINKUS ABORTION TECHNICIAN GOOD THING REPUBLIC FRENCHKISS RECORDS REPUBLIC IPECAC RECORDINGS COLUMBIA The world changes so fast that I can barely remember In contrast to her lauded 2016 album New View, Vide Noir was written and recorded over a two Featuring both ongoing Melvins’ bass player Steven Good Thing is the highly-anticipated (to put it lightly) life pre-Malone… But here we are – in the Future!!! – and which she arranged and recorded with her touring years span at Lord Huron’s Los Angeles studio and McDonald (Redd Kross, OFF!) and Butthole Surfers’, follow-up to Grammy nominated R&B singer/composer Post Malone is one of world’s unlikeliest hit-makers. band, Rebound was recorded mostly by Friedberger informal clubhouse, Whispering Pines, and was and occasional Melvins’, bottom ender Jeff Pinkus on Leon Bridges’ breakout 2015 debut Coming Home. Beerbongs & Bentleys is not only the raggedy-ass with assistance from producer Clemens Knieper. The mixed by Dave Fridmann (The Flaming Lips/MGMT). bass, Pinkus Abortion Technician is another notable Good Thing Leon’s takes music in a more modern Texas rapper’s newest album, but “a whole project… resulting collection is an entirely new sound for Eleanor, Singer, songwriter and producer Ben Schneider found tweak in the prolific band’s incredible discography. direction while retaining his renowned style. “I loved also a lifestyle” which, according to a recent Rolling exchanging live instrumentation for programmed drums, inspiration wandering restlessly through his adopted “We’ve never had two bass players,” says guitarist / my experience with Coming Home,” says Bridges. -

September 13, 2020

Vision: That all generations at St. Mary and in the surrounding community encounter Je- sus and live as His disci- ples. Mission: We are called to go out and share the Good News, making disciples who build up the Kingdom of God through meaningful prayer, effec- tive formation and loving ser- vice. SAINT MARY OF THE ANNUNCIATION MUNDELEIN Temporary Mass Schedule: www.stmaryfc.org TemporarySun. 7:30, Mass9:30,11:30 Schedule: AM Facebook:www.stmaryfc.org @stmarymundelein Sun.Tuesday, 7:30, 9:30,11:30 8:00 AM AM Facebook:Twitter: @stmarymundelein @stmarymundelein Wednesday,Tuesday, 8:00 8:00AM AM Instagram:Twitter: @stmarymundelein @stmarymundelein Thursday, 9:008:00 AM Instagram: @stmarymundelein Confessions: Saturday, 3:00–4:00 PM Confessions: Saturday, 3:00–4:00 PM Mass Intentions September 14—20, 2020 Stewardship Report Tuesday, September 15, 8:00 AM Living 69th Wedding Anniversary Sunday Collection September 6, 2020 $ 20,786..07 Matthew & Dorothy Miholic Budgeted Weekly Collection $ 22,115.38 Living Duane & Fran Schmidt Family Difference $ (1,329.31) †Salvatore & †Micheline Panettieri The Family †Genovera Larua Berner Family Current Fiscal Year-to-Date* $ 198,759.01 †Arthur “Artie” Sutko Victoria Hansen Budgeted Sunday Collections To-Date $ 221,153.85 †Archangel Capulong Wife Amy & Family †Lt. Keith O’Brien Difference $ (22,394.84) Difference vs. Last Year $ (31,220.12) Wednesday, September 16, 8:00AM †Lt. Keith O’ Brien *Note: YTD amount reflects updates by bank to postings and adjustments. †Liam Nold Gannon Family Thursday, September 17, 8:00 AM Living Lauren Jensen Shirley Monahan †Bob Soley Diana Suhling Join the Re-Opening Team †Karla Adams Parents Ed & Margaret Stahoviak The St. -

Iowa State University Alumni Association

Dear Iowa State University Graduates and Guests: Congratulations to all of the Spring 2017 graduates of Iowa State University! We are very proud of you for the successful completion of your academic programs, and we are pleased to present you with a degree from Iowa State University recognizing this outstanding achievement. We also congratulate and thank everyone who has played a role in the graduates’ successful journey through this university, and we are delighted that many of you are here for this ceremony to share in their recognition and celebration. We have enjoyed having you as students at Iowa State, and we thank you for the many ways you have contributed to our university and community. I wish you the very best as you embark on the next part of your life, and I encourage you to continue your association with Iowa State as part of our worldwide alumni family. Iowa State University is now in its 159th year as one of the nation’s outstanding land-grant universities. We are very proud of the role this university has played in preparing the future leaders of our state, nation, and world, and in meeting the needs of our society through excellence in education, research, and outreach. As you graduate today, you are now a part of this great tradition, and we look forward to the many contributions you will make. I hope you enjoy today’s commencement ceremony. We wish you all continued success! Sincerely, Steven Leath President of the University TABLE OF CONTENTS The Official University Mace .......................................................................................................... 4 The Presidential Chain of Office .................................................................................................... -

Contwe're ACT

Media contacts for Linkin Park: Dvora Vener Englefield / Michael Moses / Luke Burland (310) 248-6161 / (310) 248-6171 / (615) 214-1490 [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] LINKIN PARK ADDS BUSTA RHYMES TO 2008 SUMMER TOUR ACCLAIMED HIP HOP INNOVATOR WILL PERFORM WITH LINKIN PARK, CHRIS CORNELL, THE BRAVERY, ASHES DIVIDE ON PROJEKT REVOLUTION MAIN STAGE REVOLUTION STAGE HEADLINED BY ATREYU AND FEATURING 10 YEARS, HAWTHORNE HEIGHTS, ARMOR FOR SLEEP & STREET DRUM CORPS TOUR BEGINS JULY 16 IN BOSTON Los Angeles, CA (June 3, 2008) – Multi-platinum two-time Grammy-winning rock band Linkin Park has announced that acclaimed hip-hop innovator Busta Rhymes will join their Projekt Revolution 2008 lineup. Rhymes and Linkin Park recently collaborated on “We Made It,” the first single and video from Rhymes’ upcoming album, Blessed. By touring together, Linkin Park & Busta are taking a cue from the chorus of their song: “…we took it on the road…”. As recently pointed out in Rolling Stone’s “Summer Tour Guide,” the tour will see nine acts joining rock superstars Linkin Park, who are also offering concertgoers a digital souvenir pack that includes a recording of the band’s entire set. As the band’s co-lead vocalist Mike Shinoda told the magazine, “That puts extra pressure on us to make sure our set is different every night.” The fifth installation of Linkin Park’s raging road show will see them headlining an all-star bill that features former Soundgarden/Audioslave frontman Chris Cornell, electro-rockers The Bravery and Ashes Divide featuring Billy Howerdel, known for his work with A Perfect Circle. -

TOTAL VOCAL with Deke Sharon

03-25 DCINY.qxp_GP 3/15/18 4:15 PM Page 1 Sunday Afternoon, March 25, 2018, at 2:00 Celebrating DCINY’s 10th Anniversary Season! Iris Derke, Co-Founder and General Director Jonathan Griffith, Co-Founder and Artistic Director presents TOTAL VOCAL with Deke Sharon Deke Sharon , Guest Conductor, Arranger, & Creative Director Shelley Regner , Guest Soloist Matthew Sallee , Guest Soloist VoicePlay , Special Guests Shemesh Quartet (Mexico) , Special Guests Distinguished Concerts Singers International All arrangements by Deke Sharon unless otherwise noted TOBIAS BOSHELL I’ve Got The Music in Me (from The Sing-Off ) Distinguished Concerts International Soloists: LYDIA BROWELL, GABRIELLA DERKE, ALEXIS DILUCIA, KAT HAMMOCK, MARY LASTER, CHLOE MESOGITIS, SARA PARKER, ALEXANDRA PRODANUK, CARSON RICHMOND, HANNAH SALLEY BOBBY TROUP Route 66 (from Groove 66 ) CATHY DENNIS, HENRIK JONBACK, PONTUS WINNBERG, CHRISTIAN KARLSSON Toxic (from Pitch Perfect 3 ) JESSE HARRIS, NORAH JONES Don’t Know Why ROOM 100, PETERS TOWNSHIP HIGH SCHOOL, Featured Ensemble JOHN FOGERTY Proud Mary TONY VELONA Lollipops And Roses ITTAI MAZOR, BRUNO CISNEROS, SARA GONZALES, RUBÉN BLADES, GILBERTO SANTA ROSA Latin Medley SHEMESH QUARTET, Featured Ensemble David Geffen Hall Please make certain your cellular phone, pager, or watch alarm is switched off. 03-25 DCINY.qxp_GP 3/15/18 4:15 PM Page 2 RANDY NEWMAN When She Loved Me (from D Cappella ) DUFFY, STEVE BOOKER Mercy EVOLVE, CHESAPEAKE HIGH SCHOOL, Featured Ensemble LOUIS PRIMA Sing, Sing, Sing LIONEL RICHIE All Night Long (from -

Songwriter Endorsers.Xlsx

U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Designation of Mechanical Licensing Collective and Digital Licensee Coordinator Docket No. 2018-11 EXHIBITS 5 TO 10 TO THE DESIGNATION PROPOSAL OF MECHANICAL LICENSING COLLECTIVE PRYOR CASHMAN LLP Frank P. Scibilia Benjamin K. Semel 7 Times Square New York, New York 10036-6569 Attorneys for Mechanical Licensing Collective EXHIBIT 5 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Washington, D.C. In the Matter of': Docket No. 2018-11 DESIGNATION OF MECHANICAL LICENSING COLLECTIVE AND DIGITAL LICENSEE COORDINATOR DECLARATION OF BART HERBISON 1. My name is Bart Herbison. I am the Executive Director of the Nashville Songwriters Association International ("NSAI"), a position which I have held since 1997. I submit this declaration in support of the submission of Mechanical Licensing Collective ("MLC") to be designated as the mechanical licensing collective pursuant to the Music Modernization Act (the "MMA"). Songwriters are the backbone of the American music industry. And, since it was established in 1967, NSAI has worked tirelessly to advocate for the American songwriting profession. NSAI is now the largest not-for-profit songwriter trade association in the world, with approximately 5,000 members and approximately 100 local chapters. 3. Our mission is to advocate for songwriters' legal and economic interests and educate a new generation of American songwriters. To accomplish this mission, NSAI provides an array of services to songwriters. Some services are educational. For instance, NSAI helps songwriters improve their craft through: workshops; mentoring from experienced songwriters; feedback on songs from experienced writers and peer-to- peer review; online services for our members; regularly-held song contests and other events; pitch sessions; and in connecting aspiring professional songwriters with colleagues in the music industry. -

Korn All Albums Download Korn – Discography (1994 – 2014) UPDATE

korn all albums download Korn – Discography (1994 – 2014) UPDATE. Korn – Discography (1994 – 2014) EAC Rip | 19xCD + 4xDVD | FLAC Image & Tracks + Cue + Log | Full Scans included Total Size: 11.2 GB | 3% RAR Recovery STUDIO ALBUMS | LIVE ALBUMS | COMPILATION | EP Label: Various | Genre: Alternative Rock, Nu Metal. Korn’s cathartic alternative metal sound positioned the group among the most popular and provocative to emerge during the post-grunge era. Korn began their existence as the Bakersfield, California-based metal band LAPD, which included guitarists James “Munky” Shaffer and Brian “Head” Welch, bassist Reginald “Fieldy Snuts” Arvizu, and drummer David Silveria. After issuing an LP in 1993, the members of LAPD crossed paths with Jonathan Davis, a mortuary science student moonlighting as the lead vocalist for the local group Sexart. They soon asked Davis to join the band, and upon his arrival the quintet rechristened itself Korn. After signing to Epic’s Immortal imprint, they issued their debut album in late 1994; thanks to a relentless tour schedule that included stints opening for Ozzy Osbourne, Megadeth, Marilyn Manson, and 311, the record slowly but steadily rose in the charts, eventually going gold. Its 1996 follow- up, Life Is Peachy, was a more immediate smash, reaching the number three spot on the pop album charts. The following summer, they headlined Lollapalooza, but were forced to drop off the tour when Shaffer was diagnosed with viral meningitis. While recording their best-selling 1998 LP Follow the Leader, Korn made national headlines when a student in Zeeland, Michigan, was suspended for wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the group’s logo (the school’s principal later declared their music “indecent, vulgar, and obscene,” prompting the band to issue a cease-and-desist order). -

MACHINE FACTORY Quanam in ILLIS Madonna of the Wasps Don

Dear Readers, Inspired by the genius of Hitchcock and his films, latin luminaries such as Argento and Bava directed macabre murder-mystery thrillers, that combined the suspense with scenes of o u t r a g e o u s v i o l e n c e , s t y l i s h cinematography, and groovy soundtracks. This genre became known in their native Italy as giallo. Giallo is Italian for yellow, inspired by the lurid covers of thrillers, in the way that pulp fiction was derived from the cheap wood pulp paper of the crime stories, or Film Noir came from the chiaroscuro of the German Expressionistic lighting. We at TBRE want to bring gialli-inspired stories by POST TBRE magazine, Gritfiction Ltd, 55 Gibson Drive, Rugby, CV21 4LJ some of the best crime writers on the scene today to a wider audience, giving birth to a new literary movement in crime EMAIL [email protected] writing, NeoGiallo, and drag this much maligned genre screaming WEBSITE thebloodredexperiment.co.uk and slashing its way into the 21st Century. Have a bloody good time, TWITTER @TBRE ADVERTISING The Editors Craig Douglas Advertising Director 07809 248049 The Blood Red Experiment MAGAZINE OF GIALLO HORROR Available from the Kindle store on Ama- zon TBRE MAGAZINE TEAM Editor Jason Michel Assistant Editor Craig Douglas Art Director Richard Joseph Burton Vendor Amazon Kindle Sales ©The Blood Red Experiment 2017 Company registration no. 08765084 2 TBRE NOVEMBER 2017 The bloodied hands that bring you their works. Richard is the author of countless nov- els and short stories. -

The Grizzly, October 9, 2008

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Ursinus College Grizzly Newspaper Newspapers 10-9-2008 The Grizzly, October 9, 2008 Kristin O'Brassill Gabrielle Poretta Spencer Jones Daniel Tomblin Kristi Blust See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/grizzlynews Part of the Cultural History Commons, Higher Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Authors Kristin O'Brassill, Gabrielle Poretta, Spencer Jones, Daniel Tomblin, Kristi Blust, Kristen Stapler, Elizabeth MacDonald, Nathan Humphrey, Roger Lee, Serena Mithboakar, Laine Cavanaugh, Laurel Salvo, Josh Krigman, Spencer Cuskey, Christopher Schaeffer, Abigail Raymond, Emily McCloskey, and Jameson Cooper '"Ip Thursday, October 9, 2008 Tile student ne NAND PALIN· Spencer Jones fundamentals of the economy were strong. Two weeks before that he said we've made great economic progress Grizzly Staff Writer under George Bush's policies." Palin was quick to rise up Less than a week after the deba in defense of her running mate and rebutted, "John between John McCain and Barack McCain, in refen'ing to the fundamentals of our Obama, Joe Siden and Sarah Palin economy being strong, was talking to and faced off at Washington University talking about the American workforce, which in the first and only vice pres' is the greatest in the world with its ingenuity debate, with Gwen Ifill as mOldel'atc~r: and work ethic. That's a positive. That's Republicans and encouragement. And that's what John McCain expressed their hopes and meant." expectations for both candidates, When asked how they would handle as well as the goals each would being president should their higher ups need to achieve in order to pass away while in office, the candidates strengthen their respective laid out specifically how they would tickets. -

And Winery!), Tool’S Maynard James Keenan Wants to Be Nothing Less Than a One-Man Brand

He’s the genitalia- obsessed frontman for one of rock’s most successful bands. But with his new side project (and winery!), Tool’s Maynard James Keenan wants to be nothing less than a one-man brand. “Welcome to Arizona.” Maynard James Keenan groans it more than speaks it, a strangulated thanksforcomingdude made even less robust by body language: He has his back turned and is rushing ten feet ahead of me through the fertile arbor of the Page Springs Vineyard & Cellars. ❦ It’s noon and a brainpan-frying 95 degrees here in northern Arizona’s Verde Valley—in Keenan’s mind a natural time to have just biked the 15 miles from his home to this verdant wine-making paradise. As he presses on, he clutches a bottle of water in one hand and an iced chai in the other. Both drinks are for him. ❦ But what the notoriously reclusive rock star seems incapable of exuding in warmth, he repays in splendor, by leading me onto a deck that suspends, spectacularly, over the languid waters of Oak Creek. A tributary of the Verde PUSCIFER BY JOHN MCALLEY \\\ PHOTOGRAPHS BY JOÃO CANZIANI 82 DECEMBER 2007 WWW.SPIN.COM F_MAYNARD_DEC_FINAL_OPENER_HR3.i82 82 10/26/07 3:04:13 PM Maynard James Keenan, photo- graphed for Spin in Cornville, Arizona, October 4, 2007 WWW.SPIN.COM MONTH 2007 83 F_MAYNARD_DEC_FINAL_OPENER_HR3.i83 83 10/26/07 3:04:54 PM Thanks, but we’ll wait until you wash your hands. 84 MONTH 2007 WWW.SPIN.COM F_MAYNARD_DEC_FINAL_HR.indd 84 10/25/07 5:45:36 PM “I don’t have any talent.