Matty's Burn Trauma in William Golding's Darkness Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Golding's the Paper Men: a Critical Study درا : روا و ر ل ورق

William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical study روا و ر ل ورق : درا Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. Sabbar S. Sultan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master of Arts in English Language and Literature Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Arts and Sciences Middle East University July, 2012 ii iii iv Acknowledgment I wish to thank my parent for their tremendous efforts and support both morally and financially towards the completion of this thesis. I am also grateful to thank my supervisor Dr. Sabbar Sultan for his valuable time to help me. I would like to express my gratitude to the examining committee members and to the panel of experts for their invaluable inputs and encouragement. Thanks are also extended to the faculty members of the Department of English at Middle East University. v Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my precious father; To my beloved mother; To my two little brothers; To my family, friends, and to all people who helped me complete this thesis. vi Table of contents Subject A Thesis Title I B Authorization II C Thesis Committee Decision III D Acknowledgment IV E Dedication V F Table of Contents VI G English Abstract VIII H Arabic Abstract IX Chapter One: Introduction 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Golding and Gimmick 2 1.2 Use of Symbols 4 1.3 Golding’s Recurrent Theme (s) 5 1.4 The Relationship between Creative Writer and 7 Biographers or Critics 1.6 Golding’s Biography and Writings 8 1.7 Statement of the problem 11 1.8 Research Questions 11 1.9 Objectives of the study 12 1.10 Significance of the study 12 1.11 Limitations of the study 13 1.12 Research Methodology 14 Chapter Two: Review of Literature 2.0 Literature Review 15 Chapter Three: Discussion 3.0 Preliminary Notes 35 vii 3.1 The Creative Writer: Between Two Pressures 38 3.2 The Nature of Creativity: Seen from the Inside and 49 Outside Chapter Four 4.0 Conclusion 66 References 71 viii William Golding’s The Paper Men: A Critical Study Prepared by: Laheeb Zuhair AL Obaidi Supervised by: Dr. -

Tricks of the Light: William Golding'sudarkness Visible"

Tricks of the Light: William Golding's uDarkness Visible" PHILIP REDPATH O N AWARDING THE NOBEL PRIZE for Literature to William Golding, the Swedish Academy praised his novels for "illuminat• ing the human condition in the world today." But the vast amount of time, energy, and erudition expended in trying to interpret his work suggests that its meaning is in fact none too clear. To read a Golding novel is to be made aware that some• thing important is being said, but what that is is shrouded in ambiguity. The "gimmick" endings of the earlier novels forced the reader to reread and reconsider what he had already read, and the later writings have adopted complex forms within which events play themselves out. In The Spire Jocelin's final realiza• tion that the explanations for the erection of the spire are as complex as the branching and forking form of the appletree is a realization of the impossibility of explanation. So how "illuminat• ing" is a Golding novel? Does it impart a clear statement about man and his universe, or does it remain darkly ambiguous? If it does remain ambiguous, what is the function of this ambiguity? In order to explore these points, Golding's 1979 novel Dark• ness Visible will be discussed. This is a contemporary novel about England in the 1970's and deals with characters and events we are likely to read about in the newspapers. There are no Nean• derthal men, shipwrecked sailors, or medieval deans here to obscure our understanding of the action. Everything, therefore, should be as clear as possible. -

William Golding List

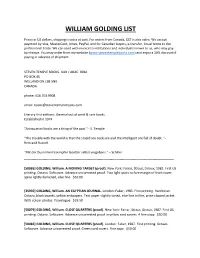

WILLIAM GOLDING LIST Prices in US dollars, shipping is extra at cost. For orders from Canada, GST is also extra. We accept payment by Visa, MasterCard, Amex, PayPal, and for Canadian buyers, e-transfer. Usual terms to the professional trade. We can send with invoice to institutions and individuals known to us, who may pay by cheque. You may order from my website (www.steventemplebooks.com) and enjoy a 10% discount if paying in advance of shipment. STEVEN TEMPLE BOOKS. ILAB / ABAC. IOBA PO BOX 45 WELLAND ON L3B 5N9 CANADA phone: 416.703.9908 email: [email protected] Literary first editions. General out of print & rare books. Established in 1974. "Antiquarian books are a thing of the past." - S. Temple “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt. “- Bertrand Russell "Mit der Dummheit kaempfen Goetter selbst vergebens." – Schiller ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- [50085] GOLDING, William. A MOVING TARGET (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1982. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof. Two light spots to fore margin of front cover, spine lightly darkened, else fine. $50.00 [35930] GOLDING, William. AN EGYPTIAN JOURNAL. London: Faber, 1985. First printing. Hardcover. Octavo, black boards, yellow endpapers. Text paper slightly toned, else fine in fine, price-clipped jacket. With colour photos. Travelogue. $19.50 [50079] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1987. First US printing. Octavo. Softcover. Advance uncorrected proof in yellow card covers. A fine copy. $50.00 [50083] GOLDING, William. CLOSE QUARTERS (proof). London: Faber, 1987. First printing. -

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels William Golding

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels William Golding 178 pages William Golding 1984 The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels 0156796589, 9780156796583 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984 Three short novels show Golding at his subtle, ironic, mysterious best. The Scorpion God depicts a challenge to primal authority as the god-ruler of an ancient civilization lingers near death. Clonk Clonk is a graphic account of a crippled youth's triumph over his tormentors in a primitive matriarchal society. Envoy Extraordinary is a tale of Imperial Rome where the emperor loves his illegitimate son more than his own arrogant, loutish heir. file download wuxin.pdf Sequel to: Close quarters Fiction ISBN:0374526389 Dec 1, 1999 313 pages William Golding Fire Down Below Sequel to: Rites of passage. Recounts the further adventures of the eighteenth-century fighting ship, converted at the close of the Napoleonic War to carry passengers and cargo Dec 1, 1999 281 pages Fiction ISBN:0374526362 William Golding Close Quarters Scorpion Jorge Luis Borges, Donald A. Yates, James East Irby Selected Stories & Other Writings A new edition of a classic work by a late forefront Argentinean writer features the 1964 augmented original text and is complemented by a biographical essay, a tribute to the 1964 Fiction ISBN:0811216993 Labyrinths 256 pages download Domestics Michle Desbordes A Story 2003 149 pages ISBN:0571210066 The Maid's Request At the behest of the French king the artist has journeyed from Italy to lead his school of students in the design and construction of a chateau in the Loire Valley. Despite the Oct 1, 1999 Fiction William Golding 278 pages Edmund Talbot recounts his voyage from England to the Antipodes, and the humiliating confrontation between the stern Captain Anderson and the nervous parson, James Colley Rites of Passage ISBN:9780374526405 Short ISBN:0143027980 Asia Now reissued with a substantial new afterword, this highly acclaimed overview of Western attitudes towards the East has become one of the canonical texts of cultural studies Orientalism 2006 416 pages Edward W. -

Novels of William Golding: an Overview

NOVELS OF WILLIAM GOLDING: AN OVERVIEW DR. NAGNATH TOTAWAD Associate Prof., Dept. of English, Member, BOS in English, Coordinator, IGNOU, SC 1610, Vivekanand Arts, S.D.Commerce & Science College, Aurangabad, 431001 (MS) INDIA William Golding is known as a prominent writer of English fiction. He is judged as an incredible fabulist, a symbolic essayist or a mythmaker. In this regard his inclination is to be called as an author of 'mytho poetic control'. His books are translated in the light of philosophy. Golding’s vision about human instinct is very well reflected in his fictions, in a general sense he has confidence in God, yet he questions if God has faith in him or in humankind. His fictions are brimming with Christian imagery yet he bids to each sort of faith in his fiction. His propensity is toward the submissive and the soul. He never endeavors to instruction. There is no agreement in his fiction. He opens human instinct for the reader so well that the reader is stunned subsequent to perusing any Golding epic and starts to scrutinize his own tendency and his job in the unceasing catastrophe on the earth-organize. Keywords: Imagery, Christ, good, evil, loss, innocence, chaos, experience etc. INTRODUCTION William Golding was a great theological novelist. Golding’s work tries to achieve apt definition of the religious implications such as the sense of guilt and shame on the one hand and as the result of wars, and inevitable urgency of more humanity, more care and more love on the other. Golding has seen the cruelty and wickedness during his service in Navy, DR. -

Rajeswar-Pal

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research S cholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations AN EVALUATION OF WILLIAM GOLDING’S POSTHUMOUS NOVEL, THE DOUBLE TONGUE Prof. Rajeswar Pal Al Jouf Univ. Sakaka (KSA) Born on September 19, 1911 in Cornwall, William Gerald Golding was a British school teacher, writer, poet and playwright He studied at Marlborough Grammar School. He got admission in Brasenose College, Oxford for the of Natural Sciences but after two years, he diverted his intention to study English Literature. He got success in his graduation in 1934 and his first volume of Poems was published in the same year. Golding joined Royal Navy and participated in Second World War with various missions before the war ended. After war Golding started a new life of teaching philosophy and science. In 1953, Golding wrote a novel, Lord of the Flies which became the tool for his success. Golding sacrificed his all time for writing and composing. He was bishop in Wordsworth’s School also. He resigned from there to save time. He went to his native home to Virginia to concentrate only on the writing. He wrote thirteen novels. He continuously started to write novels following one after other including Pincher Martin (1955), The Inheritors (1955), Free Fall (1956), The Spire (1964), The Pyramid (1967), Darkness Visible (1979), To the Ends of the Earth – trilogy (1980, 87, and 89). Golding was a multi-faceted genius and also wrote essays short fiction, and plays. His travel book is also very famous. William Golding also had some works that is still unpublished. -

William Golding: the Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WILLIAM GOLDING: THE MAN WHO WROTE LORD OF THE FLIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Carey | 592 pages | 03 Sep 2009 | FABER & FABER | 9780571231638 | English | London, United Kingdom William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies PDF Book The day before he died at 81 he was up a ladder unblocking a drainpipe. Drawing on a vast wealth of previously-unpublished material in the Golding family archive, John Carey explores the life and career of an often violently self-critical novelist who won the nobel prize for literature. John Carey has an extensive and impressive list of sources at the end of the biography. In reading this biography, I learned something of other characters, like James Lovelock, who lived for a time in the same Wiltshire village as William Golding. If you love the novels of William Golding then this first biography of the great writer will fascinate you. With Carey it's part of his integrity. John Carey. His time in the trenches gave him the insight he needed to create believable archetypes. Aug 07, Betsy rated it really liked it. He feels happy and unafraid. Welcome back. And it was largely written to serve as comfort, which helps explain its warmth: Rites of Passage to offset the difficulty of Darkness Visible and Close Quarters in the same relation to The Paper Men. Extensive use is made of his journals and letters to produce a warts'n all bio. But for him Golding would probably have died an unknown schoolteacher. As a long-time admirer of Golding, Carey can't have believed his luck when given access to a family archive containing several unpublished novels, two autobiographies, and a 5,page private journal. -

William Golding: Some Critical Considerations

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1978 William Golding: Some Critical Considerations Jack I. Biles Georgia State University Robert O. Evans University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Biles, Jack I. and Evans, Robert O., "William Golding: Some Critical Considerations" (1978). Literature in English, North America. 21. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/21 WILLIAM GOLDING DAVID ANDERSON TED E. BOYLE PHILIPPA TRISTRAM PETER WOLFE JEANNE DELBAERE-GARANT ROBERT 0. EVANS ARNOLD JOHNSTON JAY L. HALIO E. C. BUFKIN RICHARDS. CAMMAROTA DAVID SKILTON LEIGHTON HODSON MAURICE McCULLEN JACK I. BILES William Golding SOME CRITICAL CONSIDERATIONS EDITED BY Jack 1 Biles & Robert 0. Evans THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5127-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77-73705 Copyright© 1978 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION ix David Anderson IS GOLDING'S THEOLOGY CHRISTIAN? 1 Ted E. -

Golding Novel' : �Studg of William Golding's Fictional Work Submitted B Smt

THE l'6OLDING NOVEV :A STUDY *. OF • LLIAM GOLDING'S FICTIONAL WORK THESXS SUBNiTTED TO THE 60ft UNIVERSITY $s \ N.77.0 FOR s-••■•.. \ 14) it THE DEGREE OF \ D G TOR OF PHILOSOPHY KRAN JAYANT BUDKULEY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH GU A UNIVERSITY TALEIGA0 PLTE:AU A •01 20f3 • CTFTIFTJATT • dTs required under the Univqrsitu erdina.nce, I certilu that the thesis entitled The 'Golding Novel' : studg of William Golding's Fictional Work submitted b Smt. JZiran 3agant BudXulew for the award of Doctor of Philosophy . in Snglish, is a record of research done b the candidate during the period of study under mg guidance and that it has not previoustg formed the basis for the award to the candidate of arty Degree, Diploma, Yrssociateship, 7ellowship or other similar titles. Neodifte- r lir. ft. K. Josh (Research Guide) Professor and !lead. • Department of Englitiil Goa Universitu Taleigao Plateau Goa 403 203 CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE THE 'GOLDING NOVEL' • 1.1 Introduction 4 1 • 1.2 Life and Influences 1.3 Range and Diversity of Golding's York 10 1.4.1 The 'Golding Novel' 12 1.4.2 Golding's Concern with an 13 1.4.3 Isolated Settings of the Plots 15 1.4.4 The Moment of Confrontation for Golding Protagonists 17 1.4.5 'Gimmick' Ending of Golding's,Novels 19 1.4.6 Use of Literary Foils 21 1,5 Conclusion 26 References 31 CHAPTER TWO THE INITIAL 'GOLDING NOVEL' : EXPERIMENTAL PRASE 2.1.1 Introduction 32 2.1.2 'Golding Novel' : The Stages 2.1,3 The Initial Stage of the 'Golding Novel':Its Two Phases 38 2.1.4 Common Features of Golding's Novels of the Initial Stage 42 2.2.1 Novels of the 'experisental phase' 46 2.2.2 Lord of the Flies : The Plot 51 • 2.2.3 Ironical Reversal at the End of the Novel 53 • 2.2.4 Fable as an Element in Lord of the Flies 55 • • • • • • • •• 2.2.i Allegory in the Novel •. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The death of William Golding: authorship and creativity in darkness visible and the paper men Hardy, Stephen G. How to cite: Hardy, Stephen G. (2003) The death of William Golding: authorship and creativity in darkness visible and the paper men, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4091/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract The Death of William Golding: Authorship and Creativity in Darkness Visible and The Paper Men Stephen G. Hardy In the seventies and eighties William Golding was deeply responsive to the critical, anti-authorial ethos that followed the publication of Roland Barthes's "La mort de l'auteur" (1968). In Darkness Visible (1979) and The Paper Men (1984) he investigates means by which to reaffirm authorial presence. Working through paradox, he performs the authorial death in these novels, and establishes language's inadequacy as a means of conveying absolute meaning, authorial "vision," truth or revelation. -

Delphic Oracle in the Novels of William Golding Dr

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Delphic Oracle in the Novels of William Golding Dr. Prakash Bhadury Assistant Professor, NIT Hamirpur, Himanchal Pradesh, India Abstract: William Golding in his novels depicts man as a physical being in a physical world, torn between a primitive innocence and the intelligence of an evolving mind. All scientific discoveries, our awareness of our physical world are a necessary part of our evolving consciousness. The paper unravels how Golding’s mythic and allegorical world while moving around binaries attempts to find the root of the disease of evil. His central theme is to find a relationship of man to the universe and through the universe to God. Irrational faith, ignorance and material progress have obscured our vision. The root cause of man’s fall is spiritual blindness which has made man stranger to himself. Delphic Oracle-know thyself- is the hope for redemption. Key Words: Binary, Darkness, Delphic Oracle, Duality, Fall, Good & Evil, Theology. I. Introduction The world according to Golding is neither good nor evil. The perception is rooted in the human brain and in human consciousness. Evil in the Lord of the Flies (1954) exists, not as a Beast, but as an external manifestation of what is really inside and an emblematic and conceptual reduction of it are dangerous manifestations of the Fall. -

William Golding: the Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies. London: Faber and Faber

John Carey 2009: William Golding: The Man who Wrote Lord of the Flies. London: Faber and Faber. x+573 pp. ISBN 978-0-571-23163-8 Jesús Saavedra Carballido Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [email protected] At the end of his detailed biography of William Golding, John Carey remarks that today “mention of Lord of the Flies sparks recognition in a way that Golding’s own name does not” (516). This may seem unjust to those who have read the other novels, and Golding himself would have been irritated: when he reread it in 1972, he condemned its “boring and crude” style (cited 363). Still, despite huge public and critical acclaim during most of his career, Golding is remembered chiefly for that one book, which has become a massive cultural influence. This explains the subtitle of the present work. John Carey had already edited a commemorative volume on the novelist (Carey 1987). In his attempt to show that Golding was much more than a one-hit wonder, he now unearths a wealth of written documents which comprises “unpublished novels . early drafts of published novels . two autobiographical works . and a 5,000-page journal”, together with “the correspondence between Golding and his editor at Faber and Faber, Charles Monteith” (ix). So far this kind of information had only been available through Golding’s own essays and reviews, some of them collected in The Hot Gates (1965) and A Moving Target (1982), and through such biographical sketches as the one written by his daughter, Judy Carver, and appended to the last edition of Kinkead- Weekes and Gregor’s Critical Study (2002).