The Novels of William Golding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolism of Power in William Golding's Lord of the Flies

Estetisk-filosofiska fakulteten Engelska Björn Bruns The Symbolism of Power in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies Engelska C-uppsats Datum: Hösttermin 2008/2009 Handledare: Åke Bergvall Examinator: Mark Troy Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se The Symbolism of Power in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies An important theme in William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies is social power relations. These power relations are everywhere on the island, and are shown at different levels throughout the novel. These power relations are illustrated by symbols in the novel, which center on two different power systems, a democratic system, with Ralph as the head, and a dictatorial system with Jack as the leader. Sometimes these symbols are tied so closely together to both power systems that they mean different things for each of them. The aim of this essay is to investigate the different kinds of symbols that are used in the novel, and to show how they are tied to its social power relations. Those symbols that I have found are always important items that either Ralph or Jack use intentionally or unintentionally. The use of symbols is crucial to this novel, thus Golding shows us that an item is more powerful than it first seems. An important theme in William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies is social power relations. These power relations are everywhere on the island, and are shown at different levels throughout the novel. The novel, according to Kristin Olsen, concentrates on describing “the desire for power, […] the fear of other people, anger and jealousy” (2). -

The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs

I The Tarzan Series of Edgar Rice Burroughs: Lost Races and Racism in American Popular Culture James R. Nesteby Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy August 1978 Approved: © 1978 JAMES RONALD NESTEBY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ¡ ¡ in Abstract The Tarzan series of Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), beginning with the All-Story serialization in 1912 of Tarzan of the Apes (1914 book), reveals deepseated racism in the popular imagination of early twentieth-century American culture. The fictional fantasies of lost races like that ruled by La of Opar (or Atlantis) are interwoven with the realities of racism, particularly toward Afro-Americans and black Africans. In analyzing popular culture, Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1932) and John G. Cawelti's Adventure, Mystery, and Romance (1976) are utilized for their indexing and formula concepts. The groundwork for examining explanations of American culture which occur in Burroughs' science fantasies about Tarzan is provided by Ray R. Browne, publisher of The Journal of Popular Culture and The Journal of American Culture, and by Gene Wise, author of American Historical Explanations (1973). The lost race tradition and its relationship to racism in American popular fiction is explored through the inner earth motif popularized by John Cleves Symmes' Symzonla: A Voyage of Discovery (1820) and Edgar Allan Poe's The narrative of A. Gordon Pym (1838); Burroughs frequently uses the motif in his perennially popular romances of adventure which have made Tarzan of the Apes (Lord Greystoke) an ubiquitous feature of American culture. -

Anthropology

CALIFOR!:HA STATE UNIVERSI'fY, NO:R'l'HRIDGE 'l'HE EVOLUTIONARY SCHENES 0!.'' NEANDER.THAL A thesis su~nitted in partial satisfaction of tl:e requirements for the degree of Naste.r of A.rts Anthropology by Sharon Stacey Klein The Thesis of Sharon Stacey Klein is approved: Dr·,~ Nike West. - Dr. Bruce Gelvin, Chair California s·tate University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ·There are many people I would like to thank. Firs·t, the members of my corr.mi ttee who gave me their guidance and suggestions. Second, rny family and friends who supported me through this endea7cr and listened to my constant complaining. Third, the people in my office who allowed me to use my time to complete ·this project. Specifically, I appreciate the proof-reading done by my mother and the French translations done by Mary Riedel. ii.i TABLE OF' CONTENTS PAGE PRELIMINA:H.Y MATEIUALS : Al")stra-:-:t vi CHAP'I'ERS: I. Introduction 1 II. Methodology and Materials 4 III. Classification of Neanderthals 11 Species versus Subspecies Definitions of Neanderthals 16 V. The Pre-sapiens Hypothesis .i9 VI. The Unilinear Hypothesis 26 Horphological Evidence Transi tiona.l Sp.. ::;:cimens T'ool Complexes VII. The Pre-Neanderthal Hypothesis 58 Morphological Evidence Spectrum Hypothesis "Classic'1 Neanderthal's Adaptations Transitional Evidence Tool Complexes VIII. Sumnary and Conclusion 90 Heferences Cited 100 1. G~<ological and A.rchaeoloqical 5 Subdivisions of the P1eistoce!1e 2. The Polyphyletic Hypothesis 17 3. The Pre-sapiens Hypothesis 20 4. The UnilinPar Hypothesis 27 iv FIGUHES: P.Z\GE 5. Size Comparisons of Neanderthal 34 and Australian Aborigine Teeth 6. -

LORD of the FLIES by William Golding Adapted by Nigel Williams Directed by Marcus Romer Education Resource Pack Updated Sept 08 Created by Helen Cadbury

LORD OF THE FLIES by William Golding adapted by Nigel Williams directed by Marcus Romer Education Resource Pack updated Sept 08 created by Helen Cadbury ! www.pilot-theatre.com! ! ! ! ! ! 1 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Synopsis 4 ce Pack About Pilot 5 Director's Vision 6 William Golding 7 Nigel Williams 8 From Page to Stage 9 The Casting Process The Casting Breakdown 10 From Page to Stage 11 A Day in Rehearsal 12 Meet the Actor - Davood Ghadami 13 Meet the Actor - Dominic Doughty 14 d of the Flies Education Resour The Cast 15 Lor Behind the Scenes at Pilot Theatre 16 with Katie Fathers - Projects Co-ordinator WORKSHOPS AND CLASSROOM 17 ACTIVITIES Working from Themes The Island - Descriptive Language 18 - continued 19 Betrayal - Piggy and Ralph 20 Betrayal/ first script extract 21 Betrayal/ second script extract 22 Betrayal/ third script extract 23 Killing The Pig - Dramatic Tension 24 Killing the Pig/script extract 25 Killing the Pig/novel extract 26 Further Resources 27 ! www.pilot-theatre.com! ! ! ! ! ! 2 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Pilot Theatre’s 10th Anniversary Production of Lord of The Flies ce Pack Lord of the Flies is a timeless piece of work following the central theme of the journey from boyhood to manhood. William Golding described writing his novel as ‘like lamenting the lost childhood of the world’. Our production remains true to the vision of the novel, but in keeping with Pilot’s style of performance, this show is dangerous, contemporary and exciting. This education pack offers resources that give an insight into the production and that explore the themes of the play. -

Teacher and Student Resource Pack Lord of the Flies Teacher and Student Resource Pack 1 1

A NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE PRODUCTION TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 1 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK p3 2. WILLIAM GOLDING’S NOVEL p4 William Golding and Lord of the Flies Novel’s Plot Characters Themes and Symbols 3. NEW ADVENTURES AND RE:BOURNE’S LORD OF THE FLIES p11 An Introduction By Matthew Bourne Production Research Some Initial Ideas Plot Sections Similarities and Differences 4. PRODUCTION ELEMENTS p21 Set and Costume Costume Supervisor Music Lighting 5. PRACTICAL WORKSHEETS p26 General Notes Character Devising and Developing Movement 6. REFLECTING AND REVIEWING p32 Reviewing live performance Reviews and Editorials for New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s Production of Lord of the Flies 7. FURTHER WORK p32 Did You Know? It’s An Adventure Further Reading Essay Questions References Contributors LORD OF THE FLIES TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE PACK 2 1. USING THIS RESOURCE PACK This pack aims to give teachers and students further understanding of New Adventures and Re:Bourne’s production of Lord of the Flies. It contains information and materials about the production that can be used as a stimulus for written work, discussion and practical activities. There are worksheets containing information and resources that can be used to help build your own lesson plans and schemes of work based on Lord of the Flies. This pack contains subject material for Dance, Drama, English, Design and Music. Discussion and/or Evaluation Ideas Research and/or Further Reading Activities Practical Tasks Written Work The symbols above are to guide you throughout this pack easily and will enable you to use this guide as a quick reference when required. -

Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: Lord of the Flies

Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations The Adventures of The Grapes of Wrath Portnoy’s Complaint Huckleberry Finn Great Expectations A Portrait of the Alice’s Adventures in The Great Gatsby Artist as a Young Wonderland Hamlet Man All Quiet on the The Handmaid’s Tale Pride and Prejudice Western Front Heart of Darkness Ragtime As You Like It I Know Why the The Red Badge of The Ballad of the Sad Caged Bird Sings Courage Café The Iliad The Rime of the Beloved Jane Eyre Ancient Mariner Beowulf The Joy Luck Club The Rubáiyát of Billy Budd, Benito The Jungle Omar Khayyám Cereno, Bartleby the Long Day’s Journey The Scarlet Letter Scrivener, and Other Into Night A Separate Peace Tales Lord of the Flies Silas Marner Black Boy The Lord of the Rings Song of Solomon The Bluest Eye Love in the Time of The Stranger Cat on a Hot Tin Cholera A Streetcar Named Roof Macbeth Desire The Catcher in the The Man Without Sula Rye Qualities The Sun Also Rises Catch-22 The Metamorphosis The Tale of Genji The Color Purple Miss Lonelyhearts A Tale of Two Cities Crime and Moby-Dick The Tempest Punishment Night Their Eyes Were The Crucible 1984 Watching God Darkness at Noon The Odyssey Things Fall Apart Death of a Salesman Oedipus Rex To Kill a Mockingbird The Death of Artemio The Old Man and the Ulysses Cruz Sea Waiting for Godot The Divine Comedy On the Road The Waste Land Don Quixote One Flew Over the White Noise Dubliners Cuckoo’s Nest Wuthering Heights Emerson’s Essays One Hundred Years of Young Goodman Emma Solitude Brown Fahrenheit 451 The Pardoner’s Tale Frankenstein Persuasion Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations William Golding’s Lord of the Flies New Edition Edited and with an introduction by Harold Bloom Sterling Professor of the Humanities Yale University Bloom’s Modern Critical Interpretations: Lord of the Flies—New Edition Copyright © 2008 Infobase Publishing Introduction © 2008 by Harold Bloom All rights reserved. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.comThe Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Contemporary English Fiction and the works of Kazuo Ishiguro Bhawna Singh Research Scholar Lucknow University ABSTRACT The aim of this abstract is to study of memory in contemporary writings. Situating itself in the developing field of memory studies, this thesis is an attempt to go beyond the prolonged horizon of disturbing recollection that is commonly regarded as part of contemporary postcolonial and diasporic experience. it appears that, in the contemporary world the geographical mapping and remapping and its associated sense of dislocation and the crisis of identity have become an integral part of an everyday life of not only the post-colonial subjects, but also the post-apartheid ones. This inter-correlation between memory, identity, and displacement as an effect of colonization and migration lays conceptual background for my study of memory in the literary works of an contemporary writers, a Japanese-born British writer, Kazuo Ishiguro. This study is a scrutiny of some key issues in memory studies: the working of remembrance and forgetting, the materialization of memory, and the belongingness of material memory and personal identity. In order to restore the sense of place and identity to the displaced people, it may be necessary to critically engage in a study of embodied memory which is represented by the material place of memory - the brain and the body - and other objects of remembrance Vol. 1, Issue 4 (March 2016) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 80 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.comThe Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Contemporary English Fiction and the works of Kazuo Ishiguro Bhawna Singh Research Scholar Lucknow University In the eighteenth century the years after the forties observed a wonderful developing of a new literary genre. -

William Golding's Novel Conveys More Than One Idea About Individuals And

William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies” for the Common Core Worksheet 6. Theme Ideas in Lord of the Flies (teacher version) William Golding’s novel conveys more than one idea about individuals and groups. Consider information from the text supplied for you; write in the theme idea that you think the author is trying to convey through that scene. Information from the text Theme idea Piggy is overweight and asthmatic; he has weak People often judge by appearances and victimize vision; he is smart and not at all athletic. The others who seem somehow inadequate. The other boys tend to discount his ideas and make strong tend to bully the apparently weak. fun of him. The boys on the island end up at war with each War is an inevitable product of human nature. other, and war in the outside world is what led to When there is no real reason to fight, people their castaway experience in the first place. create one. When Jack first has a chance to kill a pig, he Killing, with practice, becomes easy and even hesitates. When the boys kill the sow, they are pleasurable. People can become inured to what at filled with bloodlust and savagery. first seems awful. As the novel draws to a close, it seems certain Sometimes miraculous saves do occur. (Imagine that Ralph will be killed and his head will be how different the novel would be if it ended with mounted on a stick. At the very last minute, a Ralph’s death and an island covered with burned naval officer arrives to save his life and get the out flora and fauna.) boys off the island. -

Dynasty Academic Competition Questions

DACQ January 2008 Packet 4: Dynasty Academic Competition Tossups Questions © 2007 Dynasty Academic Competition Questions. All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced or redistributed, in whole or in part, without express prior written permission solely by DACQ. Please note that non-authorized distribution of DACQ materials that involves no monetary exchange is in violation of this copyright. For permission, contact Chris Ray at [email protected]. 1. In the Civil War story arc, this character was given command of the Thunderbolts and controlled with mood stabilizers. He was created thanks to Mendel Stromm, and was the first major villain to employ the enforcers. Responsible for the death of Gwen Stacy, his weapons of choice include DNA Bombs, Razor Bats, (*) Pumpkin Bombs, and his ubiquitous glider. This identity was briefly assumed by Peter Parker's friend Harry, but is usually shown to be Norman Osbourne. FTP, identify this green-skinned nemesis of Spider Man, known for his resemblance to a small, demon-like creature. ANSWER: The Green Goblin (do NOT accept Hobgoblin) 2. This world leader include a discussion of “the social basis of the third universal theory” in his Green Book, which became extremely popular among IRA soldiers to whom this man had used ships like the MV Eksund to deliver weapons. Operation El Dorado Canyon targeted this man but instead killed his adopted daughter Hanna, and he clashed with (*) Bulgarian leaders over imprisoned health workers at Benghazi Hospital. In 2003 this man, who overthrew Idris I, agreed to payments for the Lockerbie bombing. The longest-serving head of government in the world, FTP, identify this President of Libya. -

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition

Recommended Reading for AP Literature & Composition Titles from Free Response Questions* Adapted from an original list by Norma J. Wilkerson. Works referred to on the AP Literature exams since 1971 (specific years in parentheses). A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King's Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) The American by Henry James (05, 07) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08) Another Country by James Baldwin (95) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05) Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07) As You Like It by William Shakespeare (92 05. 06) Atonement by Ian McEwan (07) Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man by James Weldon Johnson (02, 05) The Awakening by Kate Chopin (87, 88, 91, 92, 95, 97, 99, 02, 04, 07) B "The Bear" by William Faulkner (94, 06) Beloved by Toni Morrison (90, 99, 01, 03, 05, 07) A Bend in the River by V. -

Ultimate AP Book List

Yellow=Mullane Green=our library purple=free download online or on a kindle/device (We have a few kindles you may borrow from the library) A Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner (76, 00, 10) Adam Bede by George Eliot (06) (also in our library) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (80, 82, 85, 91, 92, 94, 95, 96, 99, 05, 06, 07, 08,11)(also in our library) The Aeneid by Virgil (06) Agnes of God by John Pielmeier (00) The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton (97, 02, 03, 08) Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood (00, 04, 08) All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (00, 02, 04, 07, 08, 09, 11) All My Sons by Arthur Miller (85, 90) All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (95, 96, 06, 07, 08, 10, 11) America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (95) An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (81, 82, 95, 03) American Pastoral by Philip Roth (09) The American by Henry James (05, 07, 10) Angels in America by Tony Kushner (09) Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner (10) Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (80, 91, 99, 03, 04, 06, 08, 09) You may also download it. Another Country by James Baldwin (95, 10) Antigone by Sophocles (79, 80, 90, 94, 99, 03, 05, 09, 11)-Slopek teaches it Anthony and Cleopatra by William Shakespeare (80, 91) Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler (94) Armies of the Night by Norman Mailer (76) As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (78, 89, 90, 94, 01, 04, 06, 07, 09)Also in our library. -

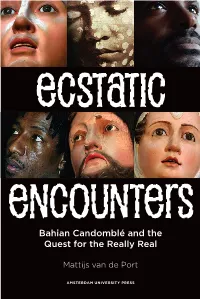

Ecstatic Encounters Ecstatic Encounters

encounters ecstatic encounters ecstatic ecstatic encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Ecstatic Encounters Bahian Candomblé and the Quest for the Really Real Mattijs van de Port AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Layout: Maedium, Utrecht ISBN 978 90 8964 298 1 e-ISBN 978 90 4851 396 3 NUR 761 © Mattijs van de Port / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2011 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents PREFACE / 7 INTRODUCTION: Avenida Oceânica / 11 Candomblé, mystery and the-rest-of-what-is in processes of world-making 1 On Immersion / 47 Academics and the seductions of a baroque society 2 Mysteries are Invisible / 69 Understanding images in the Bahia of Dr Raimundo Nina Rodrigues 3 Re-encoding the Primitive / 99 Surrealist appreciations of Candomblé in a violence-ridden world 4 Abstracting Candomblé / 127 Defining the ‘public’ and the ‘particular’ dimensions of a spirit possession cult 5 Allegorical Worlds / 159 Baroque aesthetics and the notion of an ‘absent truth’ 6 Bafflement Politics / 183 Possessions, apparitions and the really real of Candomblé’s miracle productions 5 7 The Permeable Boundary / 215 Media imaginaries in Candomblé’s public performance of authenticity CONCLUSIONS Cracks in the Wall / 249 Invocations of the-rest-of-what-is in the anthropological study of world-making NOTES / 263 BIBLIOGRAPHY / 273 INDEX / 295 ECSTATIC ENCOUNTERS · 6 Preface Oh! Bahia da magia, dos feitiços e da fé.