A Stellenbosch Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Special Trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300

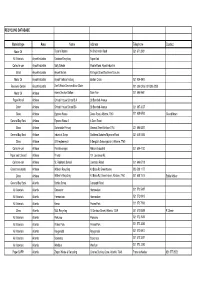

Place Name Code Hub Surch Regional A KRIEK (special trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300 BFN No AANHOU WEN, Stellenbosch 7600 SSS No ABBOTSDALE 7600 SSS No ABBOTSFORD, East London 5241 ELS No ABBOTSFORD, Johannesburg 2192 JNB No ABBOTSPOORT 0608 PTR Yes ABERDEEN (48 hrs) 6270 PLR Yes ABORETUM 3900 RCB Town Ships No ACACIA PARK 7405 CPT No ACACIAVILLE 3370 LDY Town Ships No ACKERVILLE, Witbank 1035 WIR Town Ships Yes ACORNHOEK 1 3 5 1360 NLR Town Ships Yes ACTIVIA PARK, Elandsfontein 1406 JNB No ACTONVILLE & Ext 2 - Benoni 1501 JNB No ADAMAYVIEW, Klerksdorp 2571 RAN No ADAMS MISSION 4100 DUR No ADCOCK VALE Ext/Uit, Port Elizabeth 6045 PLZ No ADCOCK VALE, Port Elizabeth 6001 PLZ No ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 DUR No ADDNEY 0712 PTR Yes ADDO 2 5 6105 PLR Yes ADELAIDE ( Daily 48 Hrs ) 5760 PLR Yes ADENDORP 6282 PLR Yes AERORAND, Middelburg (Tvl) 1050 WIR Yes AEROTON, Johannesburg 2013 JNB No AFGHANI 2 4 XXXX BTL Town Ships Yes AFGUNS ( Special Trip ) 0534 NYL Town Ships Yes AFRIKASKOP 3 9860 HAR Yes AGAVIA, Krugersdorp 1739 JNB No AGGENEYS (Special trip) 8893 UPI Town Ships Yes AGINCOURT, Nelspruit (Special Trip) 1368 NLR Yes AGISANANG 3 2760 VRR Town Ships Yes AGULHAS (2 4) 7287 OVB Town Ships Yes AHRENS 3507 DBR No AIRDLIN, Sunninghill 2157 JNB No AIRFIELD, Benoni 1501 JNB No AIRFORCE BASE MAKHADO (special trip) 0955 PTR Yes AIRLIE, Constantia Cape Town 7945 CPT No AIRPORT INDUSTRIA, Cape Town 7525 CPT No AKASIA, Potgietersrus 0600 PTR Yes AKASIA, Pretoria 0182 JNB No AKASIAPARK Boxes 7415 CPT No AKASIAPARK, Goodwood 7460 CPT No AKASIAPARKKAMP, -

Effect of Different Environmental Factors on the Performance of Sauvignon Blanc Grapevines in the Stellenbosch/Durbanville Districts of South Africa

Effect of Different Environmental Factors on the Performance of Sauvignon blanc Grapevines in the Stellenbosch/Durbanville Districts of South Africa. I. Geology, Soil, Climate, Phenology and Grape Composition W.J. Conradie1, V.A. Carey1*, V. Bonnardot2, D. Saayman3 and L. H. van Schoor1 1) ARC Infruitec-Nietvoorbij, Private Bag X5026, 7599 Stellenbosch, South Africa 2) ARC Institute for Soil, Climate and Water, Private Bag X5026, 7599 Stellenbosch, South Africa 3) Distell, Box 184, 7599 Stellenbosch, South Africa Submitted for publication: June 2002 Accepted for publication: August 2002 Key words: Geology, soil, climate, terroir, grapevine, phenology, growth, yield, must analysis A study in five commercial Sauvignon blanc vineyards, grown at different localities in the Western Cape of South Africa, was carried out over a period of seven years. These localities (four within the district of Stellenbosch and one in Durbanville) were within a radius of 15 km and underlain by different geological formations. Two experimental plots, representing different soil forms, were identified at each locality. In some cases soils could be related to the s Grapevine . materials l geologica f o s mixture m fro d develope s soil e th s case r othe n i t bu , materials t paren g underlyin were not irrigated and root distribution was mostly affected by factors such as soil moisture, compacted layers and percentage stone, and not necessarily by geological parent material. Relatively good root distribution was obtained for at least one soil from each parent material (granite, hornfels, shale). Management practices, such as liming and fertilisation, changed the chemical properties of the soil. -

Restructuring of the Rembrandt Group Circular to Shareholders and Notices of Annual General Meetings 30 August 2000

Rembrandt Group Limited Rembrandt Controlling Investments Limited Technical Investment Corporation Limited Technical and Industrial Investments Limited Restructuring of the Rembrandt Group Circular to shareholders and notices of annual general meetings 30 August 2000 Attorneys Joint sponsoring brokers Deutsche Bank Securities Deutsche Bank Securities (SA) (Pty) Ltd Hofmeyr Herbstein & Gihwala Inc. (Registration number 1995/011798/07) Reporting accountants PricewaterhouseCoopers Inc. Chartered Accountants (SA) Registered Accountants and Auditors (Registration no 1998/012055/21) Indien u ’n Afrikaanse vertaling van hierdie dokument wil hê, skakel asseblief 0800 996 164 If you have any questions regarding the restructuring of the Rembrandt Group, call the Information Agents on 0800 996 164 (or + 44 20 7335 7278 if you are phoning from outside South Africa) are acting as Information Agents to answer your questions about the restructuring. Corporate information Directors of Rembrandt Group Limited (Registration number 1948/031037/06) Johann Rupert (Chairman) P J Erasmus* E de la H Hertzog (Co-Deputy Chairman) D M Falck M H Visser (Co-Deputy Chairman and Managing Director) J Malherbe P E Beyers E Molobi* W E Bührmann J A Preller G D de Jager* P G Steyn* J W Dreyer T van Wyk * non-executive Directors of Rembrandt Controlling Investments Limited (Registration number 1952/000002/06) Johann Rupert (Chairman) D M Falck E de la H Hertzog (Co-Deputy Chairman) J Malherbe M H Visser (Co-Deputy Chairman and Managing Director) E Molobi* P E Beyers J A -

A Household Solid Waste Recycling Programme in Stellenbosch: Householders' Attitudes and Willingness Toparticip Ate

A HOUSEHOLD SOLID WASTE RECYCLING PROGRAMME IN STELLENBOSCH: HOUSEHOLDERS' ATTITUDES AND WILLINGNESS TOPARTICIP ATE MAFALLA E. MAKAU Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: Dr PH DE NECKER APRIL2006 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION I; the undersigned. hereby. dcclm·\i that the W«k ¢Mtained ih tbl:s thesis is my own Qfiglnal work and that 1 have;: oot previously in Ita entirety or In part submitted it Bt any univorsit;y for a dagrec. Signature: Daw: Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Ill ABSTRACT Municipal waste presents problems of pollution, health hazards and resource conservation. Household waste forms part of municipal solid waste that is a challenge to control due to its heterogeneity and diversity. The ever-filling landfills for the disposal of solid waste due to rapid population increase and urbanization call for urgent waste management strategies to reduce, reuse and recycle solid waste. In this study householders' attitudes, participation in recycling and willingness to participate in household solid waste recycling are investigated to design and implement a household solid waste recycling programme in Stellenbosch. Questionnaire survey data about the awareness of, attitudes towards, and participation in household waste recycling were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods in the STATISTICA V6 program. Results were displayed in frequency tables, bar charts, maps and pie charts. The same statistical program was used to fmd the relationship between the householders' willingness to participate in the household solid waste recycling programme, namely the Blue Bag Household Waste Recovery Programme (BBHWRP), and their socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics. -

A Brief History of Wine in South Africa Stefan K

European Review - Fall 2014 (in press) A brief history of wine in South Africa Stefan K. Estreicher Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA Vitis vinifera was first planted in South Africa by the Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck in 1655. The first wine farms, in which the French Huguenots participated – were land grants given by another Dutchman, Simon Van der Stel. He also established (for himself) the Constantia estate. The Constantia wine later became one of the most celebrated wines in the world. The decline of the South African wine industry in the late 1800’s was caused by the combination of natural disasters (mildew, phylloxera) and the consequences of wars and political events in Europe. Despite the reorganization imposed by the KWV cooperative, recovery was slow because of the embargo against the Apartheid regime. Since the 1990s, a large number of new wineries – often, small family operations – have been created. South African wines are now available in many markets. Some of these wines can compete with the best in the world. Stefan K. Estreicher received his PhD in Physics from the University of Zürich. He is currently Paul Whitfield Horn Professor in the Physics Department at Texas Tech University. His biography can be found at http://jupiter.phys.ttu.edu/stefanke. One of his hobbies is the history of wine. He published ‘A Brief History of Wine in Spain’ (European Review 21 (2), 209-239, 2013) and ‘Wine, from Neolithic Times to the 21st Century’ (Algora, New York, 2006). The earliest evidence of wine on the African continent comes from Abydos in Southern Egypt. -

PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND

MAMRE PELLA ATLANTIS Cape Town Tourism PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND R27 Transport Information Centre 0800 656 463 CAPE TOWN TOURISM SERVICES GENERAL TRAVEL INFORMATION: Champagne All you need to know about Cape Town P hila W d el Adam Tas e ph and travelling within the City. s i t a C Wellington o R302 a PHILADELPHIA s R304 t k KOEBERG M c RESERVATIONS: e You can do all your bookings via Cape Town Tourism a e l b m e i e R s Visitor Information Centres, online and via our Call Centre. b u an r V y n y a r J u Silwerstroom b SANPARKS BOOKINGS/SERVICES: s R304 Reservations, Activity Cards, Green e Main Beach lm a Cards & Permits at designated Visitor Information Centres. M ld DUYNEFONTEIN O R45 COMPUTICKET BOOKINGS: Book your Theatre, Events or Music Shows R312 at designated Visitor Information Centres. M19 Melkbosstrand N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 WEBTICKETS ONLINE BOOKINGS: Langenh Robben Island Trips, Kirstenbosch oven Concerts, Table Mountain Cable Car Trip at all Cape Town Tourism R304 PAARL M14 Visitor Information Centres. Suid Agter Paarl R302 R27 M58 CITY SIGHTSEEING HOP ON HOP OFF BUS TICKETS: Purchase your tickets Main West Coast at designated Visitor Information Centres. Otto Du Plessis l BLAAUWBERG e Lichtenberg w u e h p li Visse Adderley MYCITI BUS ROUTE SERVICE: Purchase and load your MyConnect Card rshok K N1 Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND at Cape Town International Airport and City Centre. Big Bay i le v West Coast M48 s on Marine m PARKLANDS Si m ROBBEN ISLAND a Wellington d ts o R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE -

Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Greater Blue Downs District Draft Baseline and Analysis Report 2019 State of the Built Environment

STATE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Greater Blue Downs District Draft Baseline and Analysis Report 2019 State of the Built Environment DRAFT Version 1.1 8 November 2019 Page 1 of 77 STATE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT CONTENTS A. STATE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................. 4 LAND USE AND DEVELOPMENT TRENDS .................................................................................... 5 1. Built environment .............................................................................................................. 6 Residential...................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Industrial ......................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Retail and Office ........................................................................................................... 8 Mixed Use .................................................................................................................................. 9 Home based enterprises ......................................................................................................... 9 Smallholdings ............................................................................................................................ 9 Agricultural land ..................................................................................................................... -

AC097 FA Cape Town City Map.Indd

MAMRE 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 km PELLA ATLANTIS WITSAND R27 PHILADELPHIA R302 R304 KOEBERG R304 I CAME FOR DUYNEFONTEIN MAP R45 BEAUTIFULR312 M19 N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 LANDSCAPES,PAARL M14 R304 R302 R27 M58 AND I FOUND Blaauwberg BEAUTIFULN1 PEOPLE Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND M48 B6 ROBBEN ISLAND PARKLANDS R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE VIEW M13 JOOSTENBERG KILLARNEY DURBANVILLE VLAKTE City Centre GARDENS KRAAIFONTEIN N1 R44 Atlantic Seaboard Northern Suburbs SONSTRAAL M5 N7 Table Bay Sunset Beach R304 Peninsula R27 BOTHASIG KENRIDGE R101 M14 PLATTEKLOOF M15 Southern Suburbs M25 EDGEMEAD TYGER VALLEY MILNERTON SCOTTSDENE M16 M23 Cape Flats M8 BRACKENFELL Milnerton Lagoon N1 Mouille Point Granger Bay M5 Helderberg GREEN POINT ACACIA M25 BELLVILLE B6 WATERFRONT PARK GOODWOOD R304 Three Anchor Bay N1 R102 CAPE TOWN M7 PAROW M23 Northern Suburbs STADIUM PAARDEN KAYAMANDI SEA POINT EILAND R102 M12 MAITLAND RAVENSMEAD Blaauwberg Bantry Bay SALT RIVER M16 M16 ELSIESRIVIER CLIFTON OBSERVATORY M17 EPPING M10 City Centre KUILS RIVER STELLENBOSCH Clifton Bay LANGA INDUSTRIA M52 Cape Town Tourism RHODES R102 CAMPS BAY MEMORIAL BONTEHEUWEL MODDERDAM Visitor Information Centres MOWBRAY N2 R300 M62 B6 CABLE WAY ATHLONE BISHOP LAVIS M12 M12 M3 STADIUM CAPE TOWN TABLE MOUNTAIN M5 M22 INTERNATIONAL Police Station TABLE RONDEBOSCH ATHLONE AIRPORT BAKOVEN MOUNTAIN NATIONAL BELGRAVIA Koeël Bay PARK B6 NEWLANDS RYLANDS Hospital M4 CLAREMONT GUGULETU DELFT KIRSTENBOSCH M54 R310 Atlantic Seaboard BLUE DOWNS JAMESTOWN B6 Cape Town’s Big 6 M24 HANOVER NYANGA Oude Kraal KENILWORTH PARK -

Name Corporate/Franchise Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Suburb

Name Corporate/Franchise Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Suburb Greater Area/City Province Main Phone GAUTENG Domino's Pizza Alberton Corporate 1 Venter St Shop 7, Jacqueline Mall Alberton Johannesburg Gauteng 011 908 3180 Domino's Pizza Bellairs Corporate Cnr Malibongwe & Bellairs Dr Shop 34, Bel Air Shopping Mall North Riding Johannesburg Gauteng 011 704 0907 Domino's Pizza Benoni Rynfield Corporate 178 Pretoria Rd Shop 2, Rynfield Shopping Centre Rynfield Benoni Gauteng 011 425 2101 Domino's Pizza Boksburg Corporate Cnr Rietfontein Rd & Rigg St Shop 2, The Square Shopping Centre Jansen Park Boksburg Gauteng 011 826 7013 Domino's Pizza Bonaero Park Franchise Cnr Tempelhof South St & Louis Botha Rd Shop 28, Aero Shopping Centre Bonaero Park Kempton Park Gauteng 011 973 1020 Domino's Pizza Brakpan Corporate 757 Voortrekker Rd Video Town, Brakpan Building Brakpan East Rand Gauteng 011 744 4723 Domino's Pizza Bram Fischer Blairgowrie Corporate 117 Bram Fischer Dr Shop 1, Canterbury Crossing Shopping Centre Blairgowrie Randburg Gauteng 011 326 1111 Domino's Pizza Bryan Park Corporate Cnr Grosvenor Rd & Cumberland Ave Shop 19A, Bryan Park Shopping Centre Bryanston Johannesburg Gauteng 011 463 2528 Domiono's Pizza Cherry Lane Corporate Cnr Fehrsen & Middel St Erf 437, Nieuw Muckleneuk Brooklyn Pretoria Gauteng 012 346 3599 Domino's Pizza Comaro Crossing Corporate Cnr Oak Stt Boundary Rd Shop FF21B Oakdene Gauteng 011 759 7269 Domino's Pizza Faerie Glen Corporate Cnr Solomon Mahlangu Dr & Haymeadow Cres Shop 4, Dischem Centre Faerie Glen Pretoria -

39542 24-12 Roadcarrier

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant December Vol. 606 24 2015 No. 39542 Desember ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 39542 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 39542 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 24 DECEMBER 2015 1 A message from Government Printing Oit)TV6, Works Notice Submissions Rule: Single notice, single email Dear Valued Customer, Over the last six months, GPW has been experiencing problems with many customers that are still not complying with GPW’s rule of single notice, single email (with proof of payment or purchase order). You are advise that effective from 18 January 2016, all notice submissions received that do no comply with this rule will be failed by our system and your notice will not be processed. In the case where a Z95, Z95Prov or TForm3 Adobe form is submitted with content, there should be a separate Adobe form completed for each notice content which must adhere to the single notice, single email rule. A reminder that documents must be attached separately in your email to GPW. (In other words, your email should have an electronic Adobe Form plus proof of payment/purchase order – 2 separate attachments – where notice content is applicable, it should also be a 3rd separate attachment). To those customers who are complying with this rule, we say Thank you! Regards, Government Printing Works This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 24 DESEMBER 2015 No. -

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials -

“We Are a Bit Blind About It”: a Qualitative Analysis of Climate Change-Related Perceptions and Communication Across South African Communities

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 “We are a Bit Blind About it”: A Qualitative Analysis of Climate Change-Related Perceptions and Communication Across South African Communities Schäfer, Mike S ; Siegen, Dario ; Mahl, Daniela Abstract: Climate change-related perceptions and communication are important factors influencing peo- ple’s support for climate change policies and individual behavior. Since research on both climate change- related perceptions and communication is biased towards Western countries and standardized research methodologies, this paper investigates perceptions across South African communities using a deductive- inductive qualitative approach. 20 individuals in three communities of a South African town were in- terviewed about their climate change-related perceptions and communication. Results show that for individual concepts of climate change, interviewees’ perceptions differed across the communities: higher educated communities had more differentiated and diverse conceptions of causes and consequences of climate change and potential countermeasures. Most interviewees, across the communities, stressed that they considered climate change as an important problem, although other social problems seemed more pressing. Interestingly, all three communities most frequently encounter the issue of climate change through new and traditional mass media, but their self-assessed knowledge about it varies widely. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2020.1736116 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-199081 Journal Article Accepted Version Originally published at: Schäfer, Mike S; Siegen, Dario; Mahl, Daniela (2020). “We are a Bit Blind About it”: A Qualitative Analysis of Climate Change-Related Perceptions and Communication Across South African Communities.