HSCA Volume X: Anti-Castro Activists and Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XII. David Ferrie

KII. DAVID FERRIE (388) In connection with its investigation of anti-Castro Cuban groups, the committee examined the activities of David William I'er- rie, an alleged associate of Lee Harvey Oswald. Among other conten- tions, it had been charged that Ferric was involved with at least one militant group of Cuban exiles and that he had made flights into Cuba in support of their counterrevolutionary activities there. (389) On Monday afternoon, November 25, 1963, Ferric, Moreover, voluntarily presented himself for questioning , to the New Orleans police, who had been looking for him in connection with the assassination of President Kennedy. (1) The New Orleans district attorney's office had earlier received information regarding a rela- tionship between Ferric and accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald,(2) including allegations that : Ferric may have been acquainted with Oswald since Oswald's days in the Civil Air Patrol youth organization in 1954-55, Ferric may have given Oswald instruction in the use of a rifle and may have hypnotized Oswald to shoot the President, and that Ferric was in Texas on the day of the assassination and may have been Oswald's getaway pilot. (3) (390) Ferric denied all the contentions, stating that at the time of the President's assassination, he had been in New Orleans, busy with court matters for organized crime figure Carlos Marcello, who had been acquitted of immigration-related charges that same day. (4) Other individuals, including Marcello, Marcello's lawyer, the lawyer's secretary, and FBI agent Regis Kennedy, supported Ferrie's alibi. (5) (391) Ferric also gave a detailed account of his whereabouts for the period from the evening of November 22, 1963, until his appearance at the New Orleans police station. -

Sophistic Synthesis in JFK Assassination Rhetoric. 24P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 532 CS 215 483 AUTHOR Gilles, Roger TITLE Sophistic Synthesis in JFK Assassination Rhetoric. PUB DATE Apr 93 NOTE 24p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication (44th, San Diego, CA, April 1-3, 1993). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Higher Education; Historiography; Popular Culture; *Presidents of the United States; *Rhetorical Criticism; *Rhetorical Theory; *United States History IDENTIFIERS 1960s; *Assassinations; Classical Rhetoric; Garrison (Jim); *Kennedy (John F); Rhetorical Stance; Social Needs ABSTRACT The rhetoric surrounding the assassination of John F. Kennedy offers a unique testing ground for theories about the construction of knowledge in society. One dilemma, however, is the lack of academic theorizing about the assassination. The Kennedy assassination has been left almost exclusively in the hands of "nonhistorians," i.e., politicians, filmmakers, and novelists. Their struggle to reach consensus is an opportunity to consider recent issues in rhetorical theory, issues of knowledge and belief, argument and narrative, history and myth. In "Rereading the Sophists: Classical Rhetoric Refigured," Susan C. Jarratt uses the sophists and their focus on "nomos" to propose "an alternative analytic to the mythos/logos antithesis" characteristic of more Aristotelian forms of rhetorical analysis. Two basic features of sophistic historiography interest Jarratt: (1) the use of narrative structures along with or opposed to argumentative structures; and (2) the rhetorical focus on history to creative broad cultural meaning in the present rather than irrefutable fact,about the past. Jarratt's book lends itself to a 2-part reading of Jim Garrison's "On the Trail of the Assassins"--a rational or Aristotelian reading and a nomos-driven or myth-making reading. -

J. R . Nelson US Deputy Marshal

STATE OF LOUISIANA SECRETARY OF STATE BATON ROUGE WADE 0. MARTIN,JR. SECRETARY OF STATE May 11, 1967 Harold Weisberg Coq d'Or Farm Hyattstown, Maryland Civil Action File No, 67-648. United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana New Orleans Division Section F Dr. Carlos Bringuier vs Gambi Publications, Inc. , et al Dear Sir: I am enclosing herewith citation served in regard to the above entitled proceeding. Yours very truly, Served on J. R . Nelson Date 5-11-67 at 10:00 a. m. Served by Tom Grace U. S. Deputy Marshal (TITLE) State Capitol, Baton Rouge RECD NUMBER DATE BANK NO. PAID BY AMOUNT CASH CHECK 5-5-67 14-72 Marquez-Diaz & Parker $4. 00 M. O. LETTERS Check returned for endorsement 7994-7995 mgl SERVICE OF PROCESS---SS-307 No. 7994 CTV. u (2.51) SUMMONS IN A CIVIL ACTION (Fatasarty D. C. Farm No. 45a Dm (4-45)) littitrb *tales Distritt Court FOR THE Eastern District of Louisiana New Orleans Division CIVIL ACTION FILE NO.. 67-648 Section F DR. ^ARLOS BRINGUIER a. 51 39 2 rou ida mmua 0 9 n Plaintiff mo SUMMONS a i to i v. an o vi o l PUBLICATIONS, INC., di mi Avi Defendant 1 Harold Weisberg, Coq 6'Or Farm, Hyattstown, Maryland, To the above named Defendant : thru the Secty. of State, State of Louisiana zorla'Ar7g1IFAXARErei‘tiarinlitigiA°g8§MAIL Mum wVAISTARVIRCGTA lazple [MT] qtrl 18 plaintiff's attorney , whose address I s 822 Gravier S Bldg., Gravier St. npawpsq rnq ern= co poIor.o e New Orle~, La. -

3. Carlos Bringuier Carlos Bringuier Was an Anti-Castro Cuban Activist In

3. Carlos Bringuier Carlos Bringuier was an anti-Castro Cuban activist in New Orleans who had repeated contact with Lee Harvey Oswald in the summer of 1963. Bringuier managed a clothing store in New Orleans, and he was also the New Orleans representative of the anti-Castro organization Directorio Revolucionaro Estudiantil (the DRE). Oswald visited Bringuier’s store in early August of 1963 and they discussed the Cuban political situation. According to Bringuier, Oswald portrayed himself as being anti-Castro and anti-communist. Several days later, someone told Bringuier that an American was passing out pro-Castro leaflets in New Orleans. Bringuier and two others went to counter-demonstrate, and Bringuier was surprised to see that Owald was the pro-Castro leafleter. Bringuier and Oswald argued and were arrested for disturbing the peace. The publicity from the altercation and trial (Oswald pleaded guilty and was fined $10 and Bringuier and his friends pleaded not guilty and the charges were dismissed) resulted in a debate on WDSU radio between Bringuier and Oswald on August 21, 1963. Bringuier testified to the Warren Commission in April of 1964. The Review Board requested access to all FBI files on Bringuier from New Orleans and Headquarters that had not already been designated for processing under the JFK Act. The Review Board designated six serials on Bringuier from New Orleans 105-1095 as assassination records. The earliest serial, dated March 16, 1962, documents attempts by a Federal agency to enlist Cuban nationals for military training. All of the other serials are dated after November 22, 1963, and document Bringuier’s interactions with Oswald in August of 1963. -

Lee Harvey Oswald's Last Lover? the Warren Commission Missed A

Lee Harvey Oswald’s Last Lover? The Warren Commission Missed A Significant JFK Assassination Connection It is reasonable to be suspicious of claims that challenge our understanding of history. But it is unreasonable to ignore evidence because it might change one’s mind or challenge the positions that one has taken in public. History shows us that new information is rarely welcome.–Edward T. Haslam Lee Harvey Oswald was an innocent man who was a government intelligence agent. He faithfully carried out assignments such as entering the USSR and pretending to be pro-Castro. Lee Harvey Oswald was a brave, good man, a patriot and a true American hero . .–Judyth Vary Baker If Judyth Vary Baker is telling the truth, it will change the way we think about the Kennedy assassination.–John McAdams Oswald in New Orleans in 1963 Lyndon B. Johnson famously remarked that Lee Harvey Oswald “was quite a mysterious fellow.” One of the most enigmatic episodes in Oswald’s adventure-filled 24-year life was his 1963 sojourn in his birthplace, New Orleans, where he arrived by bus on Apr. 25 and from which he departed by bus on Sept. 25, less than two months before the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The Warren Report The Warren Commission, which investigated the assassination and concluded that Oswald, acting alone, was the assassin, found nothing of significance in Oswald’s 1963 stay in New Orleans. The picture painted by the 1964 Warren Report is of a lowly, lonely and disgruntled leftist and pro-Castroite who occasionally pretended to be an anti-Castro rightist. -

Final Report of the ARRB

CHAPTER 6 PA RT I: TH E QU E S T F O R AD D I T I O N A L IN F O R M AT I O N A N D RE C O R D S I N FE D E R A L GO V E R N M E N T OF F I C E S A major focus of the Assassination Records fully evaluate the success of the Review Review Board’s work has been to attempt to Bo a r d’s approach is to examine the Review answer questions and locate additional infor- Bo a r d’s rec o r ds as well as the assassination mation not previously explored related to the rec o r ds that are now at the National Arc h i v e s assassination of President John F. Kennedy. and Records Administration (NARA) as a di r ect result of the Review Board’s req u e s t s . The Review Board’s “Requests for Ad d i t i o n a l Information and Records” to government Mo re o v e r , because the Review Board’s req u e s t s agencies served two purposes. First, the addi- we r e not always consistent in theme, the chap- tional requests allowed Review Board staff ter is necessarily miscellaneous in nature. members to locate new categories of assassi- nation rec o r ds in federal government files. In Scope of Chapter some files, the Review Board located new assassination rec o r ds. -

Was Lee Harvey Oswald in North Dakota

Chapter 28 Lee Harvey Oswald; North Dakota and Beyond John Delane Williams and Gary Severson North Dakota would become part of the JFK assassination story subsequent to a letter, sent by Mrs. Alma Cole to President Johnson. That letter [1] follows (the original was in Mrs. Cole’s handwriting): Dec 11, 1963 President Lyndon B. Johnson Dear Sir, I don’t know how to write to you, and I don’t know if I should or shouldn’t. My son knew Lee Harvey Oswald when he was at Stanley, North Dakota. I do not recall what year, but it was before Lee Harvey Oswald enlisted in the Marines. The boy read communist books then. He told my son He had a calling to kill the President. My son told me, he asked him. How he would know which one? Lee Harvey Oswald said he didn’t know, but the time and place would be laid before him. There are others at Stanley who knew Oswald. If you would check, I believe what I have wrote will check out. Another woman who knew of Oswald and his mother, was Mrs. Francis Jelesed she had the Stanley Café, (she’s Mrs. Harry Merbach now.) Her son, I believe, knew Lee Harvey Oswald better than mine did. Francis and I just thought Oswald a bragging boy. Now we know different. We told our sons to have nothing to do with him (I’m sorry, I don’t remember the year.) This letter is wrote to you in hopes of helping, if it does all I want is A Thank You. -

THE TAKING of AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E

THE TAKING OF AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E. Sprague Richard E. Sprague 1976 Limited First Edition 1976 Revised Second Edition 1979 Updated Third Edition 1985 About the Author 2 Publisher's Word 3 Introduction 4 1. The Overview and the 1976 Election 5 2. The Power Control Group 8 3. You Can Fool the People 10 4. How It All BeganÐThe U-2 and the Bay of Pigs 18 5. The Assassination of John Kennedy 22 6. The Assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King and Lyndon B. Johnson's Withdrawal in 1968 34 7. The Control of the KennedysÐThreats & Chappaquiddick 37 8. 1972ÐMuskie, Wallace and McGovern 41 9. Control of the MediaÐ1967 to 1976 44 10. Techniques and Weapons and 100 Dead Conspirators and Witnesses 72 11. The Pardon and the Tapes 77 12. The Second Line of Defense and Cover-Ups in 1975-1976 84 13. The 1976 Election and Conspiracy Fever 88 14. Congress and the People 90 15. The Select Committee on Assassinations, The Intelligence Community and The News Media 93 16. 1984 Here We ComeÐ 110 17. The Final Cover-Up: How The CIA Controlled The House Select Committee on Assassinations 122 Appendix 133 -2- About the Author Richard E. Sprague is a pioneer in the ®eld of electronic computers and a leading American authority on Electronic Funds Transfer Systems (EFTS). Receiving his BSEE degreee from Purdue University in 1942, his computing career began when he was employed as an engineer for the computer group at Northrup Aircraft. He co-founded the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California in 1950, and by 1953, serving as Vice President of Sales, the company had sold more computers than any competitor. -

Wtorpedo the Investigation of the Case? Who Controls The

PDC-. r i I ) January 1968 Seventy-five Cents " Tho appointed-L Ramsey Clark, who has done his best to torpedo the investigation of the case? Who controls the W CIA ? Who controls the FBI? Who controls the Archives where this evidence is locked up for so long that it is unlikely that there is anybody in this room who will be alive when it is released? This is really your property and the property of the people of this country. Who has the arrogance and the brass to prevent the people from seeing that evidence? Who indeed? "The one man who has profited most from the assassination — your friendly President, Lyndon Johnson!" Jim Garrison The Garrison Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy IM GARRISON IS AN ANGRY MAN. For him away from a vice ring or as if the the people of this country. Who has the six years now he has been the tough, Mob had attempted to use political clout arrogance and the brass to prevent the J uncompromising district attorney to get him off their backs. Only this people from seeing that evidence? Who of New Orleans, a rackets-buster without time, the file reads "Conspiracy to As- indeed ? parallel in a political freebooting state. sassinate President Kennedy," and it "The one man who has profited most He was elected on a reform platform and isn't Cosa Nostra, but the majestic might from the assassination—your friendly meant it. Turning down a Mob proposi- of the United States government which President, Lyndon Johnson!" tion that would have netted him $3000 a is trying to keep him from his duty. -

The FBI, JFK and Jim Garrison

The FBI, JFK and Jim Garrison Jim DiEugenio with help from Malcolm Blunt https://kennedysandking.com CAPA November in Dallas, 11/22/2019 1 Author/Researcher Bill Turner https://kennedysandking.com CAPA November in Dallas, 11/22/2019 2 Turner: the FBI and the JFK case Turner told me: The JFK case was a turning point for the FBI, in both its public reputation and its inner corruption. https://kennedysandking.com CAPA November in Dallas, 11/22/2019 3 The FBI and the JFK case Edwin Black's 1975 article FBI advance warnings that Kennedy would be killed that fall: 1. Chicago tip from a guy codenamed “Lee” 2. The Walter Telex 3. Richard Case Nagell How could Hoover not know William Walter's mock-up something was going to happen? of the lost telex Richard Case Nagell https://kennedysandking.com CAPA November in Dallas, 11/22/2019 4 Hoover’s Reaction Yet, in the face of all this, what was Hoover’s reaction on 11/22/63? • He calls Bobby Kennedy and says: Your brother’s been shot. • He calls 20 minutes later and says: Your brother is dead. The next day he and Clyde Tolson went to the racetrack. https://kennedysandking.com CAPA November in Dallas, 11/22/2019 5 Hoover’s Knowledge Make no mistake, Hoover knew something was going on, especially with what he was turning up in New Orleans and Mexico City. And so did Jim Garrison. https://kennedysandking.com CAPA November in Dallas, 11/22/2019 6 Hoover’s Knowledge Seven weeks after the assassination, Hoover wrote in the marginalia of a memorandum: “OK but I hope you are not being taken in. -

Stuckey Ex 3

TRANS CC DEBATE OVER STATION WDSU oft Commission No . 87b 236 ANNOUNCER : It's time now for Conversation Carte Blanche . Here is Bill Slatter . BILL SLATTER : Good evening, for the next few minutes Bill Stuckey and I, Bill whose program you've probably heard on Saturday night, "Latin Listening Post" Bill and I are going to be talking to three gentlemen the subject mainly revolving around Cuba . Our guests tonight are Lee Harvey Oswald, Secretary of the New Orleans Chapter of The Fair Play for Cuba Committee, a New York headquartered organization which is generally recognized as the principal voice of the Castro government in this country . Our second guest is Ed Butler who is Executive Vice-President of the Information Council of the Americas (INCA) which is headquartered in New Orleans and specializes in distributing anti-communist educational materials throughout Latin America, and our third guest is Carlos Bringuier, Cuban refugee and New Orleans Delegate of the Revolutionary Student Directorate one of the more active of the anti- Castro refugee organizations . Bill, if at this time you will briefly background the situation as you know it, Bill BILL STUCiOv'Y : First, for those who don't know too much about the Fair Play for Cuba Committee this is an organization that specializes primarily in distributing literature, based in New York . For the several years it has been in New York it has operated principally out of the east and out of the West Coast and a few college campuses, recently however attempts have been made to organize a chapter here in New Orleans . -

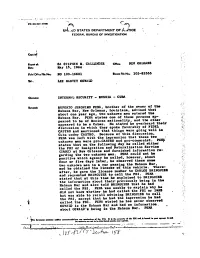

Repo. .I 441-2,4, 15-?

VD. 11•4 aim I-04110 UW. cD STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUTICE FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION GVY Repo. .I SA STEPHEN M. CALLENDER Colikft NEW ORLEANS Dow May 15, 1964 11,14 Office Rh N.•1 NO 100-16601 &tea, R1s Ku 105-82555 LEE HARVEY OSWALD INTERNAL SECURITY - RUSSIA - CUBA RUPERTO JERONIMO PENA, brother of the owner of the Habana Bar, New Orleans, Louisiana, advised that about one year ago, two unknown men entered the Habana Bar. PENA states one of these persons ap- peared to be of Mexican nationality, and the other appeared to be a Cuban. He stated he overheard their discussion in which they spoke favorably of FIDEL CASTRO and mentioned that things were going well in Cuba under CASTRO. Because of this discussion, PENA was left with the impression that these two unknown men were pro-CASTRO and pro-communist. PEI* states that on the following day he called either the FBI or Immigration and Naturalization Service (I&NS) at New Orleans and furnished information re- garding the two unknown men. PENA could not be positive which agency he called, however, about four or five days later, he observed these same two unknown men in a car passing the Habana Bar, and he obtained the license of this vehicle. There- after, be gave the license number to CARLOS BRINGUIER and requested BRINGUIER to call the FBI. PENA. stated that at this time he explained to BRINGUIER the information about their previously being in the Habana Bar and also told BRINGUIER that he had . called the FBI.