Human DNA Glycosylase NEIL1's Interactions with Downstream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Large XPF-Dependent Deletions Following Misrepair of a DNA Double Strand Break Are Prevented by the RNA:DNA Helicase Senataxin

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Large XPF-dependent deletions following misrepair of a DNA double strand break are prevented Received: 26 October 2017 Accepted: 9 February 2018 by the RNA:DNA helicase Published: xx xx xxxx Senataxin Julien Brustel1, Zuzanna Kozik1, Natalia Gromak2, Velibor Savic3,4 & Steve M. M. Sweet1,5 Deletions and chromosome re-arrangements are common features of cancer cells. We have established a new two-component system reporting on epigenetic silencing or deletion of an actively transcribed gene adjacent to a double-strand break (DSB). Unexpectedly, we fnd that a targeted DSB results in a minority (<10%) misrepair event of kilobase deletions encompassing the DSB site and transcribed gene. Deletions are reduced upon RNaseH1 over-expression and increased after knockdown of the DNA:RNA helicase Senataxin, implicating a role for DNA:RNA hybrids. We further demonstrate that the majority of these large deletions are dependent on the 3′ fap endonuclease XPF. DNA:RNA hybrids were detected by DNA:RNA immunoprecipitation in our system after DSB generation. These hybrids were reduced by RNaseH1 over-expression and increased by Senataxin knock-down, consistent with a role in deletions. Overall, these data are consistent with DNA:RNA hybrid generation at the site of a DSB, mis-processing of which results in genome instability in the form of large deletions. DNA is the target of numerous genotoxic attacks that result in diferent types of damage. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur at low frequency, compared with single-strand breaks and other forms of DNA damage1, however DSBs pose the risk of translocations and deletions and their repair is therefore essential to cell integrity. -

Phosphate Steering by Flap Endonuclease 1 Promotes 50-flap Specificity and Incision to Prevent Genome Instability

ARTICLE Received 18 Jan 2017 | Accepted 5 May 2017 | Published 27 Jun 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms15855 OPEN Phosphate steering by Flap Endonuclease 1 promotes 50-flap specificity and incision to prevent genome instability Susan E. Tsutakawa1,*, Mark J. Thompson2,*, Andrew S. Arvai3,*, Alexander J. Neil4,*, Steven J. Shaw2, Sana I. Algasaier2, Jane C. Kim4, L. David Finger2, Emma Jardine2, Victoria J.B. Gotham2, Altaf H. Sarker5, Mai Z. Her1, Fahad Rashid6, Samir M. Hamdan6, Sergei M. Mirkin4, Jane A. Grasby2 & John A. Tainer1,7 DNA replication and repair enzyme Flap Endonuclease 1 (FEN1) is vital for genome integrity, and FEN1 mutations arise in multiple cancers. FEN1 precisely cleaves single-stranded (ss) 50-flaps one nucleotide into duplex (ds) DNA. Yet, how FEN1 selects for but does not incise the ss 50-flap was enigmatic. Here we combine crystallographic, biochemical and genetic analyses to show that two dsDNA binding sites set the 50polarity and to reveal unexpected control of the DNA phosphodiester backbone by electrostatic interactions. Via ‘phosphate steering’, basic residues energetically steer an inverted ss 50-flap through a gateway over FEN1’s active site and shift dsDNA for catalysis. Mutations of these residues cause an 18,000-fold reduction in catalytic rate in vitro and large-scale trinucleotide (GAA)n repeat expansions in vivo, implying failed phosphate-steering promotes an unanticipated lagging-strand template-switch mechanism during replication. Thus, phosphate steering is an unappreciated FEN1 function that enforces 50-flap specificity and catalysis, preventing genomic instability. 1 Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, USA. -

Redundancy in Ribonucleotide Excision Repair: Competition, Compensation, and Cooperation

DNA Repair 29 (2015) 74–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect DNA Repair j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dnarepair Redundancy in ribonucleotide excision repair: Competition, compensation, and cooperation ∗ Alexandra Vaisman, Roger Woodgate Laboratory of Genomic Integrity, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892-3371, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The survival of all living organisms is determined by their ability to reproduce, which in turn depends Received 1 November 2014 on accurate duplication of chromosomal DNA. In order to ensure the integrity of genome duplication, Received in revised form 7 February 2015 DNA polymerases are equipped with stringent mechanisms by which they select and insert correctly Accepted 9 February 2015 paired nucleotides with a deoxyribose sugar ring. However, this process is never 100% accurate. To fix Available online 16 February 2015 occasional mistakes, cells have evolved highly sophisticated and often redundant mechanisms. A good example is mismatch repair (MMR), which corrects the majority of mispaired bases and which has been Keywords: extensively studied for many years. On the contrary, pathways leading to the replacement of nucleotides Ribonucleotide excision repair with an incorrect sugar that is embedded in chromosomal DNA have only recently attracted significant Nucleotide excision repair attention. This review describes progress made during the last few years in understanding such path- Mismatch repair Ribonuclease H ways in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Genetic studies in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Flap endonuclease demonstrated that MMR has the capacity to replace errant ribonucleotides, but only when the base is DNA polymerase I mispaired. -

Regulation of Yeast DNA Polymerase -Mediated Strand Displacement

Nucleic Acids Research Advance Access published March 26, 2015 Nucleic Acids Research, 2015 1 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv260 Regulation of yeast DNA polymerase ␦-mediated strand displacement synthesis by 5-flaps Katrina N. Koc, Joseph L. Stodola, Peter M. Burgers and Roberto Galletto* Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO 63110, USA Received December 22, 2014; Revised March 13, 2015; Accepted March 16, 2015 Downloaded from ABSTRACT ing the template strand (4,5). Finally, during Okazaki frag- ment maturation Pol ␦ catalyzes strand displacement DNA The strand displacement activity of DNA polymerase synthesis through the downstream Okazaki fragment to al- ␦ is strongly stimulated by its interaction with pro- low for the generation of 5 -flaps that are substrates for the liferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). However, in- FEN1 endonuclease (1–3,6,7). Strand displacement by Pol http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/ activation of the 3 –5 exonuclease activity is suffi- ␦ and FEN1 cleavage activity must be a highly coordinated cient to allow the polymerase to carry out strand dis- process to generate ligatable nicks that are then the sub- placement even in the absence of PCNA. We have strate of DNA ligase I (nick translation) (8). In this process examined in vitro the basic biochemical properties the amount of strand displacement activity needs to be reg- that allow Pol ␦-exo− to carry out strand displace- ulated to avoid generating 5 -flaps that are long enough to ment synthesis and discovered that it is regulated by bind Replication Protein A (RPA), as RPA binding is in- the 5-flaps in the DNA strand to be displaced. -

Recent Advances in Drosophila Models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Recent Advances in Drosophila Models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Fukiko Kitani-Morii 1,2,* and Yu-ichi Noto 2 1 Department of Molecular Pathobiology of Brain Disease, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto 6028566, Japan 2 Department of Neurology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto 6028566, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-75-251-5793 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 6 October 2020; Published: 8 October 2020 Abstract: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) is one of the most common inherited peripheral neuropathies. CMT patients typically show slowly progressive muscle weakness and sensory loss in a distal dominant pattern in childhood. The diagnosis of CMT is based on clinical symptoms, electrophysiological examinations, and genetic testing. Advances in genetic testing technology have revealed the genetic heterogeneity of CMT; more than 100 genes containing the disease causative mutations have been identified. Because a single genetic alteration in CMT leads to progressive neurodegeneration, studies of CMT patients and their respective models revealed the genotype-phenotype relationships of targeted genes. Conventionally, rodents and cell lines have often been used to study the pathogenesis of CMT. Recently, Drosophila has also attracted attention as a CMT model. In this review, we outline the clinical characteristics of CMT, describe the advantages and disadvantages of using Drosophila in CMT studies, and introduce recent advances in CMT research that successfully applied the use of Drosophila, in areas such as molecules associated with mitochondria, endosomes/lysosomes, transfer RNA, axonal transport, and glucose metabolism. -

Mycobacterium Smegmatis Fena Highlight Active Site

4164–4175 Nucleic Acids Research, 2018, Vol. 46, No. 8 Published online 9 April 2018 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky238 Crystal structure and mutational analysis of Mycobacterium smegmatis FenA highlight active site amino acids and three metal ions essential for flap endonuclease and 5 exonuclease activities Maria Loressa Uson1,AyalaCarl1, Yehuda Goldgur2 and Stewart Shuman1,* 1Molecular Biology Program, Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY 10065, USA and 2Structural Biology Program, Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY 10065, USA Received January 17, 2018; Revised March 19, 2018; Editorial Decision March 20, 2018; Accepted March 21, 2018 ABSTRACT exonuclease domains of bacterial DNA polymerase I (3– 7); (ii) free-standing bacterial FEN enzymes such as Es- Mycobacterium smegmatis FenA is a nucleic acid cherichia coli ExoIX, Bacillus subtilis YpcP and Mycobac- phosphodiesterase with flap endonuclease and 5 terium smegmatis FenA (7–9); (iii) bacteriophage enzymes exonuclease activities. The 1.8 A˚ crystal structure T5 Fen (10,11) and T4 Fen/RNaseH (12,13); (iv) eukaryal of FenA reported here highlights as its closest ho- FEN1 (14–16); and (v) archaeal FENs (17–19). Human mologs bacterial FEN-family enzymes ExoIX, the Pol1 ExoI is an exemplar of the FEN-like clade (20). Other mem- exonuclease domain and phage T5 Fen. Mycobac- bers of the FEN/FEN-like family include the nucleotide terial FenA assimilates three active site manganese excision repair nuclease Rad2 (21) and the Holliday junc- ions (M1, M2, M3) that are coordinated, directly and tion resolvase GEN1 (22,23). The FEN/FEN-like family via waters, to a constellation of eight carboxylate side are metal-dependent phosphodiesterases. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

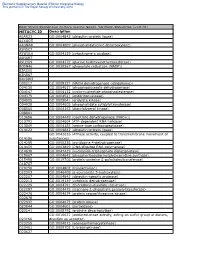

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

The Wonders of Flap Endonucleases: Structure, Function, Mechanism and Regulation

This is a repository copy of The wonders of flap endonucleases: structure, function, mechanism and regulation.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/110867/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Finger, L. D., Atack, J. M., Tsutakawa, S. et al. (4 more authors) (2012) The wonders of flap endonucleases: structure, function, mechanism and regulation. Subcellular Biochemistry, 62. pp. 301-326. ISSN 0306-0225 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4572-8_16 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Subcell Biochem. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 July 31. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Subcell Biochem. 2012 ; 62: 301–326. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4572-8_16. The Wonders of Flap Endonucleases: Structure, Function, Mechanism and Regulation L. David Finger, Department of Chemistry, Centre for Chemical Biology, Krebs Institute, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S3 7HF, UK John M. -

Junction Ribonuclease: an Activity in Okazaki Fragment Processing

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 2244–2249, March 1998 Biochemistry Junction ribonuclease: An activity in Okazaki fragment processing RICHARD S. MURANTE,LEIGH A. HENRICKSEN, AND ROBERT A. BAMBARA* Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, and Cancer Center, Box 712, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY 14642 Communicated by I. Robert Lehman, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, December 29, 1997 (received for review September 15, 1997) ABSTRACT The initiator RNAs of mammalian Okazaki and removal of RNA primers. Reconstitution assays with both fragments are thought to be removed by RNase HI and the mouse cell and SV40 replication proteins require RNase HI for 5*-3* flap endonuclease (FEN1). Earlier evidence indicated the maturation of lagging strands in vitro (12, 13). that the cleavage site of RNase HI is 5* of the last ribonucle- Although cleavage of long RNAyDNA hybrids is random, otide at the RNA-DNA junction on an Okazaki substrate. In cleavage of certain substrates is clearly structure specific. Eder current work, highly purified calf RNase HI makes this exact et al. (16) found that when a series of ribonucleotides were cleavage in Okazaki fragments containing mismatches that followed by a 39 DNA segment and annealed to DNA to form distort the hybrid structure of the heteroduplex. Furthermore, a duplex, human RNase HI preferentially cleaved to leave a even fully unannealed Okazaki fragments were cleaved. DNA segment with a 59 monoribonucleotide. In reactions Clearly, the enzyme recognizes the transition from RNA to reconstituting Okazaki fragment processing, RNase HI from DNA on a single-stranded substrate and not the RNAyDNA calf thymus similarly cleaved the RNA-DNA strand 59 to the heteroduplex structure. -

Mediated Repair of Transcribed Genes Is Linked to SCA3 Pathogenesis

Deficiency in classical nonhomologous end-joining– mediated repair of transcribed genes is linked to SCA3 pathogenesis Anirban Chakrabortya, Nisha Tapryala, Tatiana Venkovaa,1, Joy Mitrab, Velmarini Vasquezb, Altaf H. Sarkerc, Sara Duarte-Silvad,e, Weihan Huaif, Tetsuo Ashizawag, Gourisankar Ghoshf, Patricia Macield,e, Partha S. Sarkarh, Muralidhar L. Hegdeb, Xu Cheni, and Tapas K. Hazraa,2 aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555; bDepartment of Neurosurgery, Center for Neuroregeneration, The Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX 77030; cDepartment of Cancer and DNA Damage Responses, Life Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720; dSchool of Medicine, Life and Health Sciences Research Institute, University of Minho, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal; eICVS (Life and Health Sciences Research Institute)/3B’s-PT Government Associate Laboratory, 4710-057 Braga/Guimarães, Portugal; fDepartment of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093; gDepartment of Neurology, The Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX 77030; hDepartment of Neurology and Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555; and iDepartment of Neurosciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 Edited by James E. Cleaver, University of California San Francisco Medical Center, San Francisco, CA, and approved March 2, 2020 (received for review October 6, 2019) Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) is a dominantly inherited ATXN3 knockout mice showed an increase in total ubiquitinated neurodegenerative disease caused by CAG (encoding glutamine) protein levels (19). Consistently, knockdown of ATXN3 resulted in repeat expansion in the Ataxin-3 (ATXN3) gene.