A New Viewpoint Rockwell Lesson Plans for Secondary Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

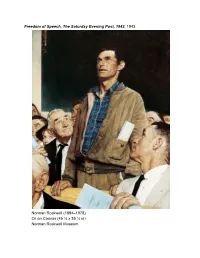

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

Denver Art Museum to Present the Power of Art in Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Traveling Exhibition Features Depictions of Franklin D

Images available upon request. Denver Art Museum to Present the Power of Art in Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Traveling exhibition features depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms alongside contemporary selections by artists responding to these freedoms today DENVER—June 19, 2020—The Denver Art Museum (DAM) will soon open Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom, an exhibition focused on the artist’s 1940s depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms and a contemporary response to these freedoms. Popularized by Rockwell’s interpretation following President Roosevelt’s 1941 speech, the freedoms include the Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. Organized and curated by the Norman Rockwell Museum and curated locally by Timothy J. Standring, Gates Family Foundation Curator at the Denver Art Museum, with contemporary works from the museum’s own collections curated by Becky Hart, Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, the exhibition will be on view from June 26, 2020 to Sept. 7, 2020, in the Anschutz and Martin & McCormick special exhibition galleries. “The presentation of Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom is the most comprehensive traveling exhibition to date of creative interpretations of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms,” said Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Mayer Director of the DAM. “We look In the 1940s, Roosevelt’s administration turned to the forward to presenting works that will challenge our visitors arts to help Americans understand the necessity of to consider the concepts of the common good, civic defending and protecting the Four Freedoms, which were engagement and civil discourse through artworks of the not immediately embraced, but later came to be known past and present.” as enduring ideals. -

THE NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM at Stockbridge

The Port olio SPRING 2000 THE NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM at Stockbridge www.nrm.org Director's Thanks On behalf of the board of directors and The Girl Rockwell our staff, 1 have the immense pleasure of announcing a most generous gift from Diane Disney Miller-the 1941 Norman Gave to Disney Rockwell oil painting Girl Reading the Post. This important Saturday Evening David Verzi, External Relations Coordinator Post cover directly ties the art of Norman Rockwell to the magazine that he was The original oil painting for the Saturday Evening Post cover of March 1, associated with for over forty-five years. It was bequeathed to the museum by the 1941, Girl Reading the Post, stands as a token of respect and friendship daughter of the other famous American between two cultural icons- the 20th-century's giants of animation illustrator, Walt Disney. We are so very and illustration. Norman Rockwell gave the painting to Walt Disney in grateful to Diane Disney Miller for her 1943 during the illustrator's brief residence in Alhambra, California. extraordinarily generous act in giving Rockwell inscribed the work, "To Walt Disney, one of the really great this painting to the Norman Rockwell artists- from an admirer, Norman Rockwell." Museum and to people all over the world who come here to experience the incredible joy of seeing original paint T he admiration was mutual, as Disney hung in the office of the famed car ings by Rockwell. once wrote to Rockwell, "I thought your toonist, then for some years it was in Four Freedoms were great. -

Annual Report 2Oo8–2Oo9

annual report 2oo8–2oo9 4o years illustration art 1 president’s letter After the fabulous recognition and its citizens. Following inspiring speeches achievements of 2008, including the from other elected officials, Laurie receipt of the National Humanities Norton Moffatt honored the vision and Medal at the White House, I really tenacity of our Founding Trustees (all anticipated a “breather” of sorts in women), who represent both our proud 2009. Fortunately, as has become heritage and great potential. From Corner the tradition of Norman Rockwell House to New England Meeting House, Museum, new highs become the Norman Rockwell Museum has assumed launching pad for new possibilities, its rightful position among our nation’s and 2009 was no exception! most visited cultural monuments. 2009 was indeed a watershed year The gathering of three generations for the Museum as we celebrated of the Rockwell family was a source our 40th anniversary. This milestone of great excitement for the Governor, captured in all its glory the hard work, our Founding Trustees, and all of us. We vision, and involvement of multiple were privileged to enjoy the sculptures generations of staff, benefactors, of Peter Rockwell, Rockwell’s youngest friends, and neighbors. son, which were prominently displayed across our bucolic campus and within Celebrating our 40th anniversary was our galleries. It was an evening to be not confined to our birthday gala on July remembered. 9th, but that gathering certainly was its epicenter. With hundreds of Museum american MUSEUMS UNDER -

Norman Rockwell: Artist Or Illustrator? | Abigail Rockwell

Norman Rockwell: Artist or Illustrator? | Abigail Rockwell http://www.huffingtonpost.com/abigail-rockwell/norman-rockwell-artist-... Distilled Perspective iOS app Android app More Desktop Alerts Log in Create Account August 25, 2015 Abigail Rockwell Become a fan Jazz singer/songwriter; granddaughter of Norman Rockwell Norman Rockwell: Artist or Illustrator? Posted: 08/24/2015 4:34 pm EDT Updated: 08/24/2015 4:59 pm EDT "Peach Crop," American Magazine, 1935 (Courtesy Norman Rockwell Family Agency) Was Norman Rockwell an artist or an illustrator? My initial thought is, "Isn't every illustrator an artist?" Yet the debate continues -- especially when it comes to Norman Rockwell. The modern take on illustration is much too limited. A reevaluation of the medium through history is called for. Thomas Buechner, director of the Brooklyn Museum, published his monumental book on Rockwell and his work in 1970: "Norman Rockwell may not be important as an artist -- whatever that is -- but he has given us a body of work which is unsurpassed in the richness and variety of its subject matter and in the professionalism -- often brilliant -- of its execution. Unlike many of his colleagues (painters with publishers instead of galleries) he lives in and for his work and so he makes it important." This statement is contradictory at best. It is the kind of ambivalence and confusion that follow my grandfather's work to this day. But Buechner then goes on to make an appeal that "illustration should be considered an aspect of the fine arts." Admittedly, it is Rockwell himself who kept publicly pronouncing, "I'm not a fine arts man, I'm an illustrator." Two separate and distinct worlds and sensibilities. -

Biography New.Pdf

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF NORMAN ROCKWELL “Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.” Norman Rockwell Born in New York City in 1894, Norman Rockwell always wanted to be an artist. At the age of fourteen, Rockwell enrolled in art classes at the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School of Art). In 1910, at the age of 16, he left high school to study art at the National Academy of Design. He soon transferred to the Art Students League, where he studied with Thomas Fogarty and George Bridgman. Fogarty’s instruction in illustration prepared Rockwell for his first commercial commissions. From Bridgman, Rockwell learned the technical skills on which he relied throughout his long career. Rockwell found success early. He painted his first commission of four Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. While still in his teens, he was hired as art director of Boys’ Life, the official publication of the Boy Scouts of America, and began a successful freelance career illustrating a variety of young people’s publications. At age 21, Rockwell’s family moved to New Rochelle, New York, a community whose residents included such famous illustrators as J.C. and Frank Leyendecker and Howard Chandler Christy. There, Rockwell set up a studio with the cartoonist Clyde Forsythe and produced work for such magazines as Life, Literary Digest and Country Gentleman. In 1916, the 22-year-old Rockwell painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, the magazine considered by Rockwell to be the “greatest show window in America.” Over the next 47 years, another 321 Rockwell covers would appear on the cover of the Post. -

Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms at Henry Ford

For more information: Melissa Foster, Media and Film Relations Manager [email protected], 313-982-6126 Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, Oct. 13, 2018- Jan. 13, 2019 (Dearborn, Mich. – Sept. 26, 2018) – Visitors to Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation this fall can see the iconic depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms by artist Norman Rockwell October 13, 2018 through January 13, 2019. Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms, an internationally touring exhibition organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum, illuminates both the historic context in which FDR articulated the Four Freedoms and the role Rockwell’s paintings played in bringing them to life for millions of people. The notion of the Four Freedoms has inspired dozens of national constitutions across the globe, yet President Roosevelt’s declaration that the United States was willing to fight for Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear, did not turn out to be the immediate triumph he had envisioned. It would take the continuous efforts of the White House, the Office of War Information, and scores of patriotic artists to give the Four Freedoms new life. Most prominent among those artists was Norman Rockwell, whose images became a national sensation in early 1943 when they were first published in The Saturday Evening Post. Roosevelt’s words and Rockwell’s pieces of art soon became inseparable in the public consciousness, with millions of reproductions bringing the Four Freedoms directly into American homes and workplaces. Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms provides a rare opportunity to see the famous paintings, as well as other works by Rockwell and his contemporaries, alongside interactive digital displays and virtual-reality technology. -

NORMAN ROCKWELL (After) - Sculptures

NORMAN ROCKWELL (After) - Sculptures Authorized Estate sculptures created after Rockwell’s original paintings. Born Norman Percevel Rockwell in New York City on February 3, 1894, Norman Rockwell knew at the age of 14 that he wanted to be an artist, and began taking classes at The New School of Art. By the age of 16, Rockwell was so intent on pursuing his passion that he dropped out of high school and enrolled at the National Academy of Design. A prolific and popular illustrator who produced 323 designs for covers of the Saturday Evening Post, Rockwell created views of American life that were often sentimental, sometimes gently satirical, and occasionally rather pointed in social commentary in a detailed style ideal for mass reproduction and consumption. Rockwell’s success stemmed to a large degree from his careful appreciation for everyday American scenes, the warmth of small-town life in particular. Often what he depicted was treated with a certain simple charm and sense of humor. “Maybe as I grew up and found the world wasn’t the perfect place I had thought it to be, I unconsciously decided that if it wasn’t an ideal world, it should be, and so painted only the ideal aspects of it,” he once said. In 1977— one year before his death—Rockwell was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford. In his speech Ford said, “Artist, illustrator and author, Norman Rockwell has portrayed the American scene with unrivaled freshness and clarity. Insight, optimism and good humor are the hallmarks of his artistic style. -

“BY POPULAR DEMAND”: the HERO in AMERICAN ART, C. 1929-1945

“BY POPULAR DEMAND”: THE HERO IN AMERICAN ART, c. 1929-1945 By ©2011 LARA SUSAN KUYKENDALL Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Charles C. Eldredge, Ph.D. ________________________________ David Cateforis, Ph.D. ________________________________ Marni Kessler, Ph.D. ________________________________ Chuck Berg, Ph.D. ________________________________ Cheryl Lester, Ph.D. Date Defended: April 11, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for LARA SUSAN KUYKENDALL certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “BY POPULAR DEMAND”: THE HERO IN AMERICAN ART, c. 1929-1945 ________________________________ Chairperson Charles C. Eldredge, Ph.D. Date approved: April 11, 2011 ii Abstract During the 1930s and 1940s, as the United States weathered the Great Depression, World War II, and dramatic social changes, heroes were sought out and created as part of an ever-changing national culture. American artists responded to the widespread desire for heroic imagery by creating icons of leadership and fortitude. Heroes took the form of political leaders, unionized workers, farmers, folk icons, historical characters, mothers, and women workers. The ideas they manifest are as varied as the styles and motivations of the artists who developed them. This dissertation contextualizes works by such artists as Florine Stettheimer, Philip Evergood, John Steuart Curry, Palmer Hayden, Dorothea Lange, Norman Rockwell, and Aaron Douglas, delving into the realms of politics, labor, gender, and race. The images considered fulfilled national (and often personal) needs for pride, confidence, and hope during these tumultuous decades, and this project is the first to consider the hero in American art as a sustained modernist visual trope. -

The Fantastical Art of James Gurney

IVINTER/S t • or 010 NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM FROM THE DIRE CTOR BOARD OF TRUSTEES Lee Williams, PreRident \lichelle Gillett, First \ 'ice President Perri Petricca, Second \ 'ice President Stevcn Spielbcrg, Third \'ice President Dear Friends, James W. I rcland, Trea.~urer Mark Selkowitz, Clerk Ruby Bridges Hall It gives me enormous pleasure to boxes for the right piece of paper or Ann Fitzpatrick Brown announce the launch of a major new photograph to accompany an article or a Daniel \1. Cain Alice Carter project at the Norman Rockwell Museum quote in a text. With the eventual com Lansing E. Cranc that will transform the accessibility of our puterization and digitization of collection Bobbie Crosby Museum collections; advance research materials, a researcher, curator, educator, 1\ I ichacl P. Dal) Catharine B. Deel) and understanding of orman Rockwell's or artist can, with the search of a key word PeLer de Seve work; preserve a unique archive of an or catalogue number, see at a glance the John Frank Dr. l'vlal') K. Grant important American artist; and link the breadth of materials linked to a particular jcffrcy Kleiser Museum to major research centers and painting, subject, historic period, or year. john Konwiscr scholars around the world. This project \ Iark Krentzman Thomas D. ~1cCatll1 has been recognized as a national model Initially, materials will be available Deborah S. l\ldd enam) in archival and collections management. solely in the Museum. Eventually, the Wendell Minor Barbara '\Icssim searchable data base will link the Brian j. Quinn ProjectNORMAN (New Media Online Museum to the Internet. -

Annual Report 2Oo3–2Oo4

annual report 2oo3–2oo4 Quebec PFIZERCORCORAN STOCKBRIDGE Red Rose Girls 18th Annual Berkshire County High School ArtP Show MOI! ar is Hometown Hero WASHINGTON DC Women in Illustration kjfoie raojfksajfe front cover 1 president’s letter We are pleased to present our Annual tial staff achievements and progress this Report for the 2003-2004 program year . year, in a climate of such constrained a report filled with accounts of mar- resources, is that the entire staff has velous exhibitions and programs . worked very hard, and very long, with local, national, international . of commitment and dedication that would continuing expert scholarship . and be difficult to ever repay, to ensure that of enthusiastic visions for our future. the Museum continues to advance in pursuit of its important mission. As you all well know, the last few years have presented significant financial Therefore, on behalf of the Board of challenges to cultural institutions Trustees, to whom I also extend my across the country given the perform- personal gratitude for their generous ance of the economy and the financial contributions of time, talent and markets, and reductions in travel and financial support, I salute and applaud tourism. This fact of our national life the outstanding achievements of our has forced us to reduce our annual wonderful staff and volunteers. Thank budget during this period by over 25%, you, thank you! which makes the achievements of our talented staff all the more remarkable. With the ongoing dedicated leadership of our staff and trustees, and the much Nevertheless, we operated this year with- appreciated support of our National in a reduced, but balanced, budget as a Council and Illustrators Advisory, our consequence of careful planning and Museum is in good hands, financially prudent management of our limited sound, and well positioned to continue resources.