View “Complicating Simplicity,” Ceglio Describes Critical Reception to the Exhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crystal Anniversary: Nmai Celebrates 15 Years with Gala and Catalog Of

PREVIEWING UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS, EVENTS, SALES AND AUCTIONS OF HISTORIC FINE ART AMrICAN ISSUE 22 July/August 2015 FMAGAZINEI AFA22.indd 2 6/2/15 10:30 AM EVENT PREVIEW: NEWPORT, RI Crystal Anniversary National Museum of American Illustration celebrates 15 years with gala and catalog of Norman Rockwell and His Contemporaries exhibition July 30, 6 p.m. National Museum of American Illustration Vernon Court 492 Bellevue Avenue Newport, RI 02840 t: (401) 851-8949 www.americanillustration.org o commemorate the 15th anniversary of the National TMuseum of American Illustration (NMAI), the museum will host a gala and live auction July 30 in connection with its current exhibition Norman Rockwell and His Contemporaries, running through October 12. The gala features cocktails, dining, dancing and celebrity appearances, while the auction includes work by Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish, and Howard Chandler Christy, among others. An auction highlight is a portrait of former President John F. Kennedy by Rockwell. The illustration was completed for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post and was done during the Cuban missile crisis. By using a three-quarter portrait pose with Kennedy’s chin resting on his hand and a dark background, the artist was able to express the heaviness Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Portrait of John F. Kennedy, The Saturday Evening Post cover, April 6, of the president’s decisions to the 1963. Oil on canvas, 22 x 18 in., signed lower right. Estimate: $4/6 million viewer. “We lived through it. It was a big The portrait was the second and last Phoebus on Halzaphron, a short story by deal for us. -

Tips for Families

GRADE 2 | MODULE 3 TIPS FOR FAMILIES WHAT IS MY GRADE 2 STUDENT LEARNING IN MODULE 3? Wit & Wisdom® is our English curriculum. It builds knowledge of key topics in history, science, and literature through the study of excellent texts. By reading and responding to stories and nonfiction texts, we will build knowledge of the following topics: Module 1: A Season of Change Module 2: The American West Module 3: Civil Rights Heroes Module 4: Good Eating In Module 3, we will study a number of strong and brave people who responded to the injustice they saw and experienced. By analyzing texts and art, students answer the question: How can people respond to injustice? OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS Picture Books (Informational) ▪ Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington, Frances E. Ruffin; illustrations, Stephen Marchesi ▪ I Have a Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; paintings, Kadir Nelson ▪ Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, Ruby Bridges ▪ The Story of Ruby Bridges, Robert Coles; illustrations, George Ford ▪ Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh Poetry ▪ “Words Like Freedom,” Langston Hughes ▪ “Dreams,” Langston Hughes OUR CLASS WILL EXAMINE THIS PHOTOGRAPH ▪ Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, James Karales OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE ARTICLES ▪ “Different Voices,” Anna Gratz Cockerille ▪ “When Peace Met Power,” Laura Helwegs OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS ▪ “Ruby Bridges Interview” ▪ “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” ▪ “The Man Who Changed America” For more resources, -

Ruby Bridges, Cultural Materialism and Prayer As a Material Object

Ruby Bridges, Cultural Materialism and Prayer as a Material Object In 1960, six-year old Ruby Bridges was the first African American girl to integrate a white Southern elementary school in the state of Louisiana. On November 14, escorted by four US Marshalls, Ruby walked through the doors of William Frantz Elementary, Louisiana. As she walked, she was confronted by an angry mob of white protestors and segregationists who yelled profanities and threw objects (Boyd, 2013), yet Ruby persisted, and in so doing, Ruby came to mark a pivotal point in US history. Ruby found herself as the target of racial violence and hatred due to a confluence of factors that began with the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, (347 U.S. 483,1954) that ruled ‘separate-but-equal’ schools were unconstitutional. Although the law required integrated schools, many white people strongly opposed the Court’s ruling and they continued to block changes in the school. Ruby, who had recently relocated from Mississippi to Louisiana with her parents, was enrolled in an all-white school that was demographically closer to her home. In 1960, with the encouragement from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who fought for racial equality, Ruby’s parents agreed to have her sent to this school. Robert Coles, a Harvard professor and psychiatrist volunteered to provide counseling for Ruby and her family. As an enthralled witness to the daily terror Ruby experienced as she attempted to walk to school, Coles relocated to Louisiana to volunteer free counselling services for Ruby and her family. -

“American Chronicles: the Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” Published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky

“American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell at TAM” published in Artdish, March 2011 2011 Jane Richlovsky Norman Rockwell's painting "Discovery", currently on display at the Tacoma Art Museum, depicts a pajama-clad young boy finding a Santa Claus suit and false beard in Dad's bureau drawer, incriminating evidence of the old man's fakery. The picture appeared on the cover of the December 29, 1956 Saturday Evening Post. It's hard at first to get past the boy's facial expression. His eyes are popping out of his head, in a way that irritatingly foreshadows the ubiquitous Macauley Caulkin "Home Alone" publicity shot. However unfortunate this association, the expression is so utterly unconvincing as a portrayal of having one's cherished mythology punctured, that one can't help but think the kid never believed in Santa in the first place. Considering that this is one of many Rockwell paintings that repeatedly revisit the Santa-unmasking narrative over decades, you have to wonder: Is the guy responsible for our vision of the American Myth perhaps telling us we shouldn't be so surprised or upset that it's all made up? I've always found sunny, idealized, 1950's-style Leave-it-to-Beaver archetypal America intriguing, compelling, and horrifying. I'm far from alone in this, but I have spent more time than most people immersed in its ephemera, interrogating, digesting, cutting up, reconfiguring, and spitting back out endless images from midcentury domestic magazines. Imagine my shock when, after all that, putting together a show of the resulting paintings, I encounter a dealer's misbegotten press release, or an enthusiastic patron, praising what I thought was my scathing critique as a fond, nostalgic look back at a "simpler time". -

Children of Stuggle Learning Guide

Library of Congress LIVE & The Smithsonian Associates Discovery Theater present: Children of Struggle LEARNING GUIDE: ON EXHIBIT AT THE T Program Goals LIBRARY OF CONGRESS: T Read More About It! Brown v. Board of Education, opening May T Teachers Resources 13, 2004, on view through November T Ernest Green, Ruby Bridges, 2004. Contact Susan Mordan, (202) Claudette Colvin 707-9203, for Teacher Institutes and T Upcoming Programs school tours. Program Goals About The Co-Sponsors: Students will learn about the Civil Rights The Library of Congress is the largest Movement through the experiences of three library in the world, with more than 120 young people, Ruby Bridges, Claudette million items on approximately 530 miles of Colvin, and Ernest Green. They will be bookshelves. The collections include more encouraged to find ways in their own lives to than 18 million books, 2.5 million recordings, stand up to inequality. 12 million photographs, 4.5 million maps, and 54 million manuscripts. Founded in 1800, and Education Standards: the oldest federal cultural institution in the LANGUAGE ARTS (National Council of nation, it is the research arm of the United Teachers of English) States Congress and is recognized as the Standard 8 - Students use a variety of national library of the United States. technological and information resources to gather and synthesize information and to Library of Congress LIVE! offers a variety create and communicate knowledge. of program throughout the school year at no charge to educational audiences. Combining THEATER (Consortium of National Arts the vast historical treasures from the Library's Education Associations) collections with music, dance and dialogue. -

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

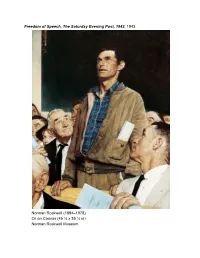

2-A Rockwell Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943, 1943 Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) Oil on Canvas (45 ¾ x 35 ½ in) Norman Rockwell Museum NORMAN ROCKWELL [1894–1978] 19 a Freedom of Speech, The Saturday Evening Post, 1943 After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, What is uncontested is that his renditions were not only vital to America was soon bustling to marshal its forces on the home the war effort, but have become enshrined in American culture. front as well as abroad. Norman Rockwell, already well known Painting the Four Freedoms was important to Rockwell for as an illustrator for one of the country’s most popular maga- more than patriotic reasons. He hoped one of them would zines, The Saturday Evening Post, had created the affable, gangly become his statement as an artist. Rockwell had been born into character of Willie Gillis for the magazine’s cover, and Post read- a world in which painters crossed easily from the commercial ers eagerly followed Willie as he developed from boy to man world to that of the gallery, as Winslow Homer had done during the tenure of his imaginary military service. Rockwell (see 9-A). By the 1940s, however, a division had emerged considered himself the heir of the great illustrators who left their between the fine arts and the work for hire that Rockwell pro- mark during World War I, and, like them, he wanted to con- duced. The detailed, homespun images he employed to reach tribute something substantial to his country. a mass audience were not appealing to an art community that A critical component of the World War II war effort was the now lionized intellectual and abstract works. -

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—A Partnership with for Freedoms—Activates Civic Engagement Through Art Work Creation, Saturday, Oct 20

BAM 50 State Initiative Art Project—a partnership with For Freedoms—activates civic engagement through art work creation, Saturday, Oct 20 Free public event will be led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy Oct 5, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) has partnered with For Freedoms in an afternoon of civic engagement on Saturday, Oct 20 from 1–3pm at the South Site Plaza (Lafayette Ave, corner of Flatbush Ave). Attendees will participate in an art-making project, led by Brooklyn visual artist Katherine Toukhy, to create and share social and political statements with the community. Images of finished artworks will be photographed and displayed on BAM’s outdoor digital signpost on the corner of Flatbush Ave and Lafayette Ave—running on a loop until the mid-term elections in November. BAM’s VP of Education and Community Engagement Coco Killingsworth said, “We’re excited to join with For Freedoms and Katherine Toukhy in gathering community members for this creative civic activation. We hope this event inspires all of us to use our voices to engage in the democratic process.” For Freedoms started in 2016 as a platform for civic engagement, discourse, and direct action for artists in the United States. Inspired by Norman Rockwell’s 1943 painting of the four universal freedoms articulated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1941—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—For Freedoms seeks to use art to deepen public discussions of civic issues and core values, and to clarify that citizenship in American society is deepened by participation, not by ideology. -

Inspirational People

Inspirational People FUEL THE PASSION TO CREATE POSITIVE CHANGE WITH BOOKS FROM THESE INSPIRATIONAL PEOPLE! Art © 2019 by Bob Bianchini Whether reading with family or friends, this activity brochure will spark important and thoughtful conversations. This brochure includes: This is Your Time • Discussion Questions It’s Trevor Noah: Born a Crime • Discussion Questions THIS IS YOUR TIME Reader Discussion and Writing Guide Guide your family or group’s discussion about this inspirational letter to today’s young activists from RUBY BRIDGES herself. Art used under license from Shutterstock.com. Photo courtesy of author. Art used under license from Shutterstock.com. Language Advisory: This Is Your Time contains some images of racist language and other offensive epithets. This guide was written by Kimiko Cowley-Pettis. A Brief Overview of the Civil Rights Movement in America THE FIGHT TO END THE SEGREGATION OF PUBLIC FACILITIES The Supreme Court made a ruling in the May 18, Plessy v. Ferguson case that established 1896 the separate but equal doctrine. President Lyndon Johnson signed the July 2, Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing 1964 racial discrimination in employment, voting, and the use of public facilities. TIMELINE OF THE FIGHT FOR SCHOOL INTEGRATION The Massachusetts Supreme Court Black and white children went to separate heard arguments about school schools in New Orleans. A judge ordered segregation in Roberts v. the City that four black girls attend two all-white December 4, of Boston. Months later, it declared 1960 schools—McDonogh Elementary School 1849 that school integration would and William Frantz Elementary School. only increase racial prejudice. -

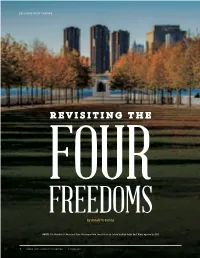

REVISITING the FOUR FREEDOMS by Donald M

EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE REVISITING THE FOUR FREEDOMS By Donald M. Bishop PHOTO: The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, located on an island in New York's East River, opened in 2012 3 • MARINE CORPS UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION • SUMMER 2019 EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE Modern political warfare now includes both cyber and information operations. At MCU, Bren Chair of Strategic Communications Donald Bishop focuses his teaching and presentations on the “information” or “influence” dimension of conflict – disinformation, propaganda, persuasion, hybrid warfare – now enabled by the internet and social media. And he emphasizes that Americans, as they confront violent extremism and other threats, must know and be confident of the American values they defend. "Thanks, Grandpa, for coming to my game." Why look back at The Four Freedoms? First, in my classes at Marine Corps University, I’ve discovered that the current "I enjoyed it too, Jack. We men in our eighties don't get generation of Marines have never heard of them. Of Norman out as often as we wish. Seeing you score a run was Rockwell’s four famous paintings, they have seen only one – something. But you know, I noticed something else today. the family at Thanksgiving – and they don’t know they were "When you were at the plate, it carried me back to part of a series. Second – when Americans must articulate watching my older brother in the batter's box. You held the “what we’re for” (rather than “what we’re against”) – whether bat like he did. You have the same stance and the same in the war on terrorism or in a future of great power competi- swing. -

Denver Art Museum to Present the Power of Art in Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Traveling Exhibition Features Depictions of Franklin D

Images available upon request. Denver Art Museum to Present the Power of Art in Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom Traveling exhibition features depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms alongside contemporary selections by artists responding to these freedoms today DENVER—June 19, 2020—The Denver Art Museum (DAM) will soon open Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom, an exhibition focused on the artist’s 1940s depictions of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms and a contemporary response to these freedoms. Popularized by Rockwell’s interpretation following President Roosevelt’s 1941 speech, the freedoms include the Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want and Freedom from Fear. Organized and curated by the Norman Rockwell Museum and curated locally by Timothy J. Standring, Gates Family Foundation Curator at the Denver Art Museum, with contemporary works from the museum’s own collections curated by Becky Hart, Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, the exhibition will be on view from June 26, 2020 to Sept. 7, 2020, in the Anschutz and Martin & McCormick special exhibition galleries. “The presentation of Norman Rockwell: Imagining Freedom is the most comprehensive traveling exhibition to date of creative interpretations of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms,” said Christoph Heinrich, Frederick and Jan Mayer Director of the DAM. “We look In the 1940s, Roosevelt’s administration turned to the forward to presenting works that will challenge our visitors arts to help Americans understand the necessity of to consider the concepts of the common good, civic defending and protecting the Four Freedoms, which were engagement and civil discourse through artworks of the not immediately embraced, but later came to be known past and present.” as enduring ideals.