National Identity Cards Lecture Delivered at the University of Edinburgh on January 19, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breaking out of Britain's Neo-Liberal State

cDIREoCTIONmFOR THE pass DEMOCRATIC LEFT Breaking out of Britain’s Neo-Liberal State January 2009 Gerry Hassan and Anthony Barnett 3 4 r Tr hink e b m m u N PIECES 3 4 Tr hink e b m u N PIECES Breaking out of Britain’s Neo-Liberal State Gerry Hassan and Anthony Barnett “In the big-dipper of UK politics, the financial crisis suddenly re-reversed these terms. Gordon Brown excavated a belief in Keynesian solutions from his social democratic past and a solidity of purpose that was lacking from Blair’s lightness of being” Compass publications are intended to create real debate and discussion around the key issues facing the democratic left - however the views expressed in this publication are not a statement of Compass policy. Breaking out of Britain’s Neo-Liberal State www.compassonline.org.uk PAGE 1 Breaking out of Britain’s reduced for so many, is under threat with The British Empire State Building Neo-Liberal State no state provisions in place for them. The political and even military consequences England’s “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 Gerry Hassan and Anthony Barnett could well be dire. created a framework of compromise between monarchy and Parliament. It was Nonetheless we should celebrate the followed by the union of England with possible defeat of one aspect of neo- Scotland of 1707, which joined two he world we have lived in, liberal domination. It cheered the different countries while preserving their created from the twin oil-price destruction of a communist world that distinct legal traditions. Since then the T shockwaves of 1973 and 1979 was oppressive and unfree. -

The Case of the National Identity Card in the UK Paul Beynon-Davies University of Wales, Swansea, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) European Conference on Information Systems ECIS 2005 Proceedings (ECIS) 2005 Personal Identification in the Information Age: The Case of the National Identity Card in the UK Paul Beynon-Davies University of Wales, Swansea, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2005 Recommended Citation Beynon-Davies, Paul, "Personal Identification in the Information Age: The asC e of the National Identity Card in the UK" (2005). ECIS 2005 Proceedings. 27. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2005/27 This material is brought to you by the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in ECIS 2005 Proceedings by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERSONAL IDENTIFICATION IN THE INFORMATION AGE: THE CASE OF THE NATIONAL IDENTITY CARD IN THE UK Paul Beynon-Davies, European Business Management School, University of Wales Swansea, Singleton Park, Swansea, UK, [email protected] Abstract The informatics infrastructure supporting the Information Society requires the aggregation of data about individuals in electronic records. Such data structures demand that individuals be uniquely identified and this is critical to the necessary processes of authentication, identification and enrolment associated with the use of e-Business, e-Government and potentially e-Democracy systems. It is also necessary to the representation of human interactions as data transactions supporting various forms of governance structure: hierarchies, markets and networks. -

Conference Programme Online Educa Berlin 2007

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Please see www.online-educa.com/pre-conference for Pre-Conference Workshops and Forums taking place on November 28 Please note that the agenda for Online Educa Berlin is subject to change (23 November 2007) Page 1 Session Codes & Themes COR = E-Learning in the Corporate and Company Context UNI = Learning Futures in Higher Education SCH = Classroom Learning and ICT PUB = Public and Professional E-Learning LIF = Lifelong and Informal Learning DES = Designing Teaching and Learning with Digital Media and Tools GAM = Games and Simulations in Support of Learning MOB = M-Learning: Learning in the Hands of the Learner WEB = Web 2.0 linked to Education 2.0 VID = Video in Support of Online Learning QUA = Quality and E-Learning EVA = Assessment and Evaluation ACC = Online Learning, Equality and Accessibility RES = The Application of Research Outcomes in the TEL Field POL = E-Learning Policy and Practice KES = Knowledge Exchange Sessions GEN = General Sessions BPS = Best Practice Sessions DEM = Demonstration Sessions NET = Networking Sessions Page 2 Thursday, November 29, 2007 9:15 – 11:00 Opening Plenary Potsdam I/III The Opening Plenary for Online Educa Berlin 2007 will be chaired by Dr. Harold Elletson, The New Security Foundation, UK and will feature key-note presentations by: Hon. Elizabeth Ohene, Minister of State, Ministry of Education, Science & Sports, Ghana Prof. Sugata Mitra, Newcastle University, UK & Chief Scientist Emeritus, NIIT Ltd., India The “Hole in the Wall” Experiments: Self-Organising Systems in Primary -

Election 2001 Campaign Spending We Are an Independent Body That Was Set up by Parliament

Election 2001 Campaign spending We are an independent body that was set up by Parliament. We aim to gain public confidence and encourage people to take part in the democratic process within the United Kingdom by modernising the electoral process, promoting public awareness of electoral matters, and regulating political parties. On 1 April 2002, The Boundary Committee for England (formerly the Local Government Commission for England) became a statutory committee of The Electoral Commission. Its duties include reviewing local election boundaries. © The Electoral Commission 2002 ISBN: 1-904363-08-3 1 Contents List of tables, appendices and returns 2 Conclusions 45 Preface 5 Political parties 45 Executive summary 7 Third parties 46 Spending by political parties 7 Candidates’ expenses 46 Spending by third parties 7 Future work programme 47 Spending by candidates 7 Introduction 9 Appendices The role of The Electoral Commission 10 Appendix 1 49 Campaign expenditure by political parties 11 Appendix 2 50 The spending limit 12 Appendix 3 87 Interpretation of legislation 12 Appendix 4 89 Public and media interest in the campaign 13 Appendix 5 90 Commission guidance 13 Appendix 6 97 Completing and reviewing the expenditure returns 13 Candidates’ election expenses at the Analysis of returns 14 2001 general election 99 Northern Ireland analysis 15 Great Britain analysis 17 Problems in categorising expenditure 18 Breakdown of total expenditure: the main three British parties 18 Other parties and trends 19 Apportionment and spending in England, Scotland -

Centre for Political & Constitutional Studies King's College London

CODIFYING – OR NOT CODIFYING – THE UNITED KINGDOM CONSTITUTION: THE EXISTING CONSTITUTION Centre for Political & Constitutional Studies King’s College London Series paper 2 2 May 2012 1 Centre for Political and Constitutional Studies The Centre for Political and Constitutional Studies is a politically non-aligned body at King’s College London, engaged in and promoting interdisciplinary studies and research into contemporary political and constitutional issues. The Centre’s staff is led by Professor Robert Blackburn, Director and Professor of Constitutional Law, and Professor Vernon Bogdanor, Research Professor, supported by a team of funded research fellows and academic staff at King’s College London specialising in constitutional law, contemporary history, political science, comparative government, public policy, and political philosophy. www.kcl.ac.uk/innovation/groups/ich/cpcs/index. Authorship This report of the Centre for Political and Constitutional Studies was written by Dr Andrew Blick, Senior Research Fellow, in consultation with Professor Robert Blackburn, Director, and others at the Centre, as part of its impartial programme of research for the House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee into Mapping the Path towards Codifying – or Not Codifying – the United Kingdom Constitution, funded by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust and the Nuffield Foundation. Previous publications in this series Codifying – or Not Codifying – the United Kingdom Constitution: A Literature Review, Series Paper 1, February 2011 © -

Members 1979-2010

Members 1979-2010 RESEARCH PAPER 10/33 28 April 2010 This Research Paper provides a complete list of all Members who have served in the House of Commons since the general election of 1979 to the dissolution of Parliament on 12 April 2010. The Paper also provides basic biographical and parliamentary data. The Library and House of Commons Information Office are frequently asked for such information and this Paper is based on the data we collate from published sources to assist us in responding. This Paper replaces an earlier version, Research Paper 09/31. Oonagh Gay Richard Cracknell Jeremy Hardacre Jean Fessey Recent Research Papers 10/22 Crime and Security Bill: Committee Stage Report 03.03.10 10/23 Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Bill [HL] [Bill 79 of 2009-10] 08.03.10 10/24 Local Authorities (Overview and Scrutiny) Bill: Committee Stage Report 08.03.10 10/25 Northern Ireland Assembly Members Bill [HL] [Bill 75 of 2009-10] 09.03.10 10/26 Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report 11.03.10 10/27 Unemployment by Constituency, February 2010 17.03.10 10/28 Transport Policy in 2010: a rough guide 19.03.10 10/29 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2010/11 26.03.10 10/30 Digital Economy Bill [HL] [Bill 89 of 2009-10] 29.03.10 10/31 Economic Indicators, April 2010 06.04.10 10/32 Claimant Count Unemployment in the new (2010) Parliamentary 12.04.10 Constituencies Research Paper 10/33 Contributing Authors: Oonagh Gay, Parliament and Constitution Centre Richard Cracknell, Social and General Statistics Section Jeremy Hardacre, Statistics Resources Unit Jean Fessey, House of Commons Information Office This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

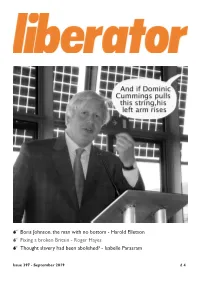

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

Why Have a Bill of Rights?

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 26 Number 1 Symposium: The Bill of Rights Yesterday and Today: A Bicentennial pp.1-19 Celebration Symposium: The Bill of Rights Yesterday and Today: A Bicentennial Celebration Why Have a Bill of Rights? William J. Brennan Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation William J. Brennan Jr., Why Have a Bill of Rights?, 26 Val. U. L. Rev. 1 (1991). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol26/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Brennan: Why Have a Bill of Rights? Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 26 Fall 1991 Number 1 ARTICLES WHY HAVE A BILL OF RIGHTS? WILLIAM J. BRENNAN, JR.- It is a joy as well as an honor to speak to you today about a subject that has been at the heart of my service on the Supreme Court. The American Bill of Rights, guaranteeing freedom of speech, religion, assembly, and the press, along with other important protections against arbitrary or oppressive government action, provides a noble expression and shield of human dignity. Together with the Civil War Amendments, outlawing slavery and involuntary servitude and ensuring all citizens equal protection of the laws and due process of law, the Bill of Rights stands as a constant guardian of individual liberty. -

Autonomy, Community, and Traditions of Liberty: the Contrast of British and American Privacy Law

AUTONOMY, COMMUNITY, AND TRADITIONS OF LIBERTY: THE CONTRAST OF BRITISH AND AMERICAN PRIVACY LAW INTRODUCTION I give the fight up: let there be an end, A privacy, an obscure nook for me. I want to be forgotten even by God. -Robert Browning1 Although most people do not wish to be forgotten "even by God," individuals do expect their community to refrain from intrusive regula- tion of the intimate aspects of their lives. Thus, the community must strike a balance between legitimate community concerns and the individ- ual's interest in personal autonomy. In free societies, the community os- tensibly speaks through a popularly constituted government. Thus, government protection of privacy rights is a measure of a society's com- mitment to liberty and, in a broader sense, autonomy. Privacy law re- flects the tolerance of a nation. Although privacy is only one example of 2 autonomy, privacy rights are a substantial subset of personal autonomy. Thus, examining privacy rights is one way to evaluate the general mea- sure of liberty a society confers on its members. But, even if one recognizes the need for privacy, the right of privacy cannot be absolute. The existence of political community requires the relinquishment of certain rights, prerogatives, and freedoms.3 As John Locke described, individuals must cede some rights and prerogatives that 1. Paracelsus,in 1 THE POEMS 118, 127 (J. Pettigrew ed. 1981). 2. The autonomy/privacy relation is a difficult matter. Privacy relates to personal autonomy, but they are not coextensive. For example, autonomy would reach public acts such as one's public dress or a speech given at a public gathering, acts that are not encompassed in any notion of privacy. -

William Cobbett, His Children and Chartism

This is a repository copy of William Cobbett, his children and Chartism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82896/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Chase, MS (2015) William Cobbett, his children and Chartism. In: Grande, J and Stevenson, J, (eds.) William Cobbett, Romanticism and the Enlightenment: Contexts and Legacy. The Enlightenment World, 31 . Pickering & Chatto . ISBN 9781848935426 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 COBBETT, HIS CHILDREN AND CHARTISM Malcolm Chase William Cobbett was part of the ‘mental furniture’ of the Chartists, contrary to one biographer’s claim that they had ‘little in common’ with him.1 James Watson, one of London’s leading radical publishers remembered his mother ‘being in the habit of reading Cobbett’s Register’.2 Growing up in a Chartist home, W. -

Membership Roll

FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY - NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω MEMBERSHIP ROLL Illustrious Royal Order of Saint Januarius Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George Royal Order of Francis I DELEGATION OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND March 2015 The Grand Master HRH Prince Charles of Bourbon Two Sicilies, Duke of Castro, and HRH Princess Camilla of Bourbon Two Sicilies, Duchess of Castro, His Eminence Renato Raffaele, Cardinal Martino, Grand Prior of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George The Prayer of the Constantinian Order 1 The History of the Order in Great Britain 2 The History of the Order in Ireland 4 Council of the Delegation of Great Britain and Ireland 6 Members of the Delegation of Great Britain and Ireland 8 Illustrious Royal Order of Saint Januarius 8 » In the Category of Knight 8 Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George 9 » In the Category of Justice 9 » In the Special Category 10 » In the Category of Grace 10 » In the Category of Merit 12 » » In the Category of Office 15 RoyalRecepients Order of of BenemerentiFrancis I Medals 1715 Post Nominals of Decorations 20 Obituaries 21 The Prayer of the Constantinian Order Almighty and Merciful Father, King of kings and Lord of lords, in Your immeasurable goodness You have called me into the ranks of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George, Your Knight and Martyr. May I never cease to emulate our heavenly patron and with alacrity fol- low in the footsteps of Your Only-begotten Son, Who is our Alpha and Omega, our Beginning and End. -

Harvard University's

A joint project of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and Harvard Law School Long-Term Legal Strategy Project for Preserving Security and Democratic Freedoms in the War on Terrorism Philip B. Heymann, Harvard Law School Juliette N. Kayyem, Kennedy School of Government Sponsored by The National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government administered the Long-Term Legal Strategy Project from April 2003 - November 2004. The Belfer Center provides leadership in advancing policy-relevant knowledge about the most important challenges of international security and other critical issues where science, technology, environmental policy, and international affairs intersect. To learn more about the Belfer Center, visit www.bcsia.ksg.harvard.edu. Long-Term Legal Strategy Project Attn: Meredith Tunney John F. Kennedy School of Government 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-5275 www.ksg.harvard.edu/bcsia/longtermlegalstrategy www.mipt.org/Long-Term-Legal-Strategy.asp Harvard University’s Long-Term Legal Strategy Project for Preserving Security and Democratic Freedoms in the War on Terrorism Board of Advisors All members of the Board of Advisors agreed with the necessity to evaluate the legal terrain governing the “war on terrorism.” This final Report is presented as a distillation of views and opinions based on a series of closed-door meetings of the Board. The advisors have from time to time been offered the opportunity to express views or make suggestions relating to the matters included in this Report, but have been under no obligation to do so, and the contents of the Report do not represent the specific beliefs of any given member of the Board.