My System: a Treatise on Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1 “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION 2013, Botswana Chess Review In this Issue; BY: KEENESE NEOYAME KATISENGE 1. Historic World Chess Federation’s Visit to Botswana 2. Field Performance 3. Administration & Developmental Programs BCF PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR 4. Social Responsibility, Marketing and Publicity / Sponsorships B “Checkmate” is the first edition of BCF e-Newsletter. It will be released on a quarterly basis with a review of chess events for the past period. In Chess circles, “Checkmate” announces the end of the game the same way this newsletter reviews performance at the end of a specified period. The aim of “Checkmate” is to maintain contact with all stakeholders, share information with interesting chess highlights as well as increase awareness in a BNSC Chair Solly Reikeletseng,Mr Mogotsi from Debswana, cost-effective manner. Mr Bobby Gaseitsewe from BNSC and BCF Exo during The 2013 Re-ba bona-ha Youth Championships 2013, Botswana Chess Review Under the leadership of the new president, Tshenolo Maruatona,, Botswana Chess continues to steadily Minister of Youth, Sports & Culture Hon. Shaw Kgathi and cement its place as one of the fastest growing the FIDE Delegation during their visit to Botswana in 2013 sporting codes in the country. BCF has held a number of activities aimed at developing and growing the sport in the country. “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION | Issue 1 2 2013 Review Cont.. The president of the federation, Mr Maruatona attended two key International Congresses, i.e Zonal Meeting held during The -

Issue 16, June 2019 -...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA

...CHESSPROBLEMS.CA Contents 1 Originals 746 . ISSUE 16 (JUNE 2019) 2019 Informal Tourney....... 746 Hors Concours............ 753 2 Articles 755 Andreas Thoma: Five Pendulum Retros with Proca Anticirce.. 755 Jeff Coakley & Andrey Frolkin: Multicoded Rebuses...... 757 Arno T¨ungler:Record Breakers VIII 766 Arno T¨ungler:Pin As Pin Can... 768 Arno T¨ungler: Circe Series Tasks & ChessProblems.ca TT9 ... 770 3 ChessProblems.ca TT10 785 4 Recently Honoured Canadian Compositions 786 5 My Favourite Series-Mover 800 6 Blast from the Past III: Checkmate 1902 805 7 Last Page 808 More Chess in the Sky....... 808 Editor: Cornel Pacurar Collaborators: Elke Rehder, . Adrian Storisteanu, Arno T¨ungler Originals: [email protected] Articles: [email protected] Chess drawing by Elke Rehder, 2017 Correspondence: [email protected] [ c Elke Rehder, http://www.elke-rehder.de. Reproduced with permission.] ISSN 2292-8324 ..... ChessProblems.ca Bulletin IIssue 16I ORIGINALS 2019 Informal Tourney T418 T421 Branko Koludrovi´c T419 T420 Udo Degener ChessProblems.ca's annual Informal Tourney Arno T¨ungler Paul R˘aican Paul R˘aican Mirko Degenkolbe is open for series-movers of any type and with ¥ any fairy conditions and pieces. Hors concours compositions (any genre) are also welcome! ! Send to: [email protected]. " # # ¡ 2019 Judge: Dinu Ioan Nicula (ROU) ¥ # 2019 Tourney Participants: ¥!¢¡¥£ 1. Alberto Armeni (ITA) 2. Rom´eoBedoni (FRA) C+ (2+2)ser-s%36 C+ (2+11)ser-!F97 C+ (8+2)ser-hsF73 C+ (12+8)ser-h#47 3. Udo Degener (DEU) Circe Circe Circe 4. Mirko Degenkolbe (DEU) White Minimummer Leffie 5. Chris J. Feather (GBR) 6. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

CHESS REVIEW but We Can Give a Bit More in a Few 250 West 57Th St Reet , New York 19, N

JULY 1957 CIRCUS TIME (See page 196 ) 50 CENTS ~ scription Rate ONE YEAR $5.50 From the "Amenities and Background of Chess-Play" by Ewart Napier ECHOES FROM THE PAST From Leipsic Con9ress, 1894 An Exhibition Game Almos t formidable opponent was P aul Lipk e in his pr ime, original a nd pi ercing This instruc tive game displays these a nd effective , Quite typica l of 'h is temper classical rivals in holiUay mood, ex is the ",lid Knigh t foray a t 8. Of COU I'se, ploring a dangerous Queen sacrifice. the meek thil'd move of Black des e r\" e~ Played at Augsburg, Germany, i n 1900, m uss ing up ; Pillsbury adopted t he at thirty moves an hOlll" . Tch igorin move, 3 . N- B3. F A L K BEE R COU NT E R GAM BIT Q U EE N' S PAW N GA ME" 0 1'. E. Lasker H. N . Pi llsbury p . Li pke E. Sch iffers ,Vhite Black W hite Black 1 P_K4 P-K4 9 8-'12 B_ KB4 P_Q4 6 P_ KB4 2 P_KB4 P-Q4 10 0-0- 0 B,N 1 P-Q4 8-K2 Mate announred in eight. 2 P- K3 KN_ B3 7 N_ R3 3 P xQP P-K5 11 Q- N4 P_ K B4 0 - 0 8 N_N 5 K N_B3 12 Q-N3 N-Q2 3 B-Q3 P- K 3? P-K R3 4 Q N- B3 p,p 5 Q_ K2 B-Q3 13 8-83 N-B3 4 N-Q2 P-B4 9 P-K R4 6 P_Q3 0-0 14 N-R3 N_ N5 From Leipsic Con9ress. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

Aron Nimzowitsch My System & Chess Praxis

Aron Nimzowitsch My System & Chess Praxis Translated by Robert Sherwood New In Chess 2016 Contents Translator’s Preface............................................... 9 My System Foreword..................................................... 13 Part I – The Elements . 15 Chapter 1 The Center and Development...............................16 1. By development is to be under stood the strategic advance of the troops to the frontier line ..............................16 2. A pawn move must not in and of itself be regarded as a develo ping move but should be seen simply as an aid to develop ment ........................................16 3. The lead in development as the ideal to be sought ..........18 4. Exchanging with resulting gain of tempo.................18 5. Liquidation, with subsequent development or a subsequent liberation ..........................................20 6. The center and the furious rage to demobilize it ...........23 7. On pawn hunting in the opening ......................28 Chapter 2 Open Files .............................................31 1. Introduction and general remarks.......................31 2. The origin (genesis) of the open file ....................32 3. The ideal (ultimate purpose) of every operation along a file ..34 4. The possible obstacles in the way of a file operation ........35 5. The ‘restricted’ advance along one file for the purpose of relin quishing that file for another one, or the indirect utilization of a file. 38 6. The outpost .......................................39 Chapter 3 The Seventh and Eighth Ranks ..............................44 1. Introduction and general remarks. .44 2. The convergent and the revo lutionary attack upon the 7th rank. .44 3. The five special cases on the seventh rank . .47 Chapter 4 The Passed Pawn ........................................75 1. By way of orientation ...............................75 2. The blockade of passed pawns .........................77 3. -

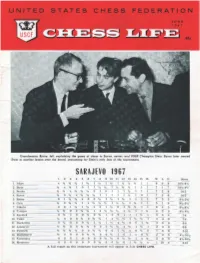

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

Chess Review

MARCH 1968 • MEDIEVAL MANIKINS • 65 CENTS vI . Subscription Rat. •• ONE YEAR $7.S0 • . II ~ ~ • , .. •, ~ .. -- e 789 PAGES: 7'/'1 by 9 inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 ideo variations 1704 practical variations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all variations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr, Max Euwe, Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch, and many other noted authorities This Jatest and immense work, the mo~t exhaustive of i!~ kind, e:x · plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not teft hanging in mid.position with the query : What bappens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. Firsl come the moves with footnotes leading to the key position. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low perlinenl observations, illustrated by "Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print. Practical and Supplementary Variations, well annotated, exemplify the effective possibilities. Each line is appraised : or spacious poging and a ll the +, - = . The large format-71/2 x 9 inches- is designed for ease of rcad· other appurtenances of exquis· ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuffling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal lines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation·identify· ing diagrams are other plus features. chess books! In addition to all else, fhi s book contains 439 complete ga mes- a golden trea.mry in itself! ORDER FROM CHESS REVIEW 1- --------- - - ------- --- - -- - --- -I I Please send me Chess Openings: Theory and Practice at $12.50 I I Narne • • • • • • • • • • . -

Formation Attack Strategies

Formation Attack Strategies Joel Johnson Edited by: Eric Hammond © Joel Johnson, June 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from Joel Johnson. Edited by: Eric Hammond Cover Photography: Barry M. Evans Cover Design: Joel Johnson Game Searching: Joel Johnson, Richard J. Cowan, William Parker Proofreading: Joel Johnson Game Contributors: Brian Wall, Jack Young, Clyde Nakamura, James Rizzitano, Keith Hayward, Hal Terrie, Richard Cowan, Jesús Seoane, William Parker, Domingos Perego Linares Diagram and Linares Figurine fonts ©1993-2003 by Alpine Electronics, Steve Smith Alpine Electronics 703 Ivinson Ave. Laramie, WY 82070 Email: Alpine Chess Fonts ([email protected]) Website: http://www.partae.com/fonts/ CONTENTS Preface 9 Kudos 9 Purpose of the Book 10 Harry Lyman 9 Education 10 Chess In The Schools 10 Chess Friendships and Sportsmanship 10 Eulogy for Harry Lyman (by Shelby Lyman) 10 Harry Lyman Games 10 Passing The Torch 9 Joshua Zhu 10 Richard Cowan 10 Matthew Miller 10 Luke Miller 10 Noah Raskin 10 Eric Hammond 10 Jimi Sullivan 10 Phil Terrill 10 Austin Terrill 10 Bailey Vidler 10 Clark Vidler 10 Michael Oldehoff 10 Bogdan Anghel 10 Jamie Aronson 10 Rich Desmarais 10 Nick Desmarais 10 Joe Range 10 Bernabe Garcia 10 Nancy Jones 10 Adam Nehmeh 10 Paul Nehmeh 10 Section A – Attack Philosophies 11 Personal Development 12 Frame of Mind 15 Dual Aspects of Chess 30 Chess Mechanics -

Hypermodern Game of Chess the Hypermodern Game of Chess

The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower Foreword by Hans Ree 2015 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Hypermodern Game of Chess The Hypermodern Game of Chess by Savielly Tartakower © Copyright 2015 Jared Becker ISBN: 978-1-941270-30-1 All Rights Reserved No part of this book maybe used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. PO Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Translated from the German by Jared Becker Editorial Consultant Hannes Langrock Cover design by Janel Norris Printed in the United States of America 2 The Hypermodern Game of Chess Table of Contents Foreword by Hans Ree 5 From the Translator 7 Introduction 8 The Three Phases of A Game 10 Alekhine’s Defense 11 Part I – Open Games Spanish Torture 28 Spanish 35 José Raúl Capablanca 39 The Accumulation of Small Advantages 41 Emanuel Lasker 43 The Canticle of the Combination 52 Spanish with 5...Nxe4 56 Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch and Géza Maróczy as Hypermodernists 65 What constitutes a mistake? 76 Spanish Exchange Variation 80 Steinitz Defense 82 The Doctrine of Weaknesses 90 Spanish Three and Four Knights’ Game 95 A Victory of Methodology 95 Efim Bogoljubow -

Chess-Moves-July-Aug

July / August 2006 NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION £1.50 Magnificent Bequest to the British Chess Federation John Robinson the well known and much esteemed chess organiser and arbiter died on 1st February 2006. John dedicated much of his life to chess in many forms, now comes the news of a magnificent bequest to the British Chess Federation of the order of £650,000. Of this sum about £120,000 will be invested in the British Chess Federation Permanent Invested Fund enabling John’s expressed wish of support for the British Championship to be carried out, the remainder of the bequest will be invested in the John Robinson Youth Chess Trust a Charitable Trust which means no inheritance tax is payable on John’s bequest. It is proposed that this money should be invested in such a way that the capital may be retained and the accumulated income used for grants from the Trust. This Legacy provides stability for the future of the Championship and for Junior Chess. If anyone wishes to consider a bequest to ECF/BCF please contact the Office for further details. Editorial The establishment of the National Chess Library is progressing well. The rooms have now been cleared and the specialised ECF News shelving is in place. The books are in the process of being unpacked with book plates Nominations for being added. As soon as an opening date is fixed this will be announced. There are many Election at the ECF AGM other exciting projects, other than books The voluntary posts to be elected at being discussed with Hastings University, 0YD no later than 13.30 on Wednesday it is amazing how one venture can lead to the AGM on 1 October 006 are: 13 September 2006.