Macdonagh, Thomas by Lawrence William White

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

De Búrca Rare Books

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 141 Spring 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 141 Spring 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Pennant is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 141: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our front and rear cover is illustrated from the magnificent item 331, Pennant's The British Zoology. -

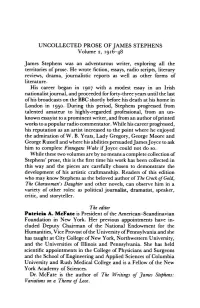

UNCOLLECTED PROSE of JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48

UNCOLLECTED PROSE OF JAMES STEPHENS Volume 2, 1916-48 James Stephens was an adventurous writer, exploring all the territories of prose. He wrote fiction, essays, radio scripts, literary reviews, drama, journalistic reports as well as other forms of literature. His career began in 1907 with a modest essay in an Irish nationalist journal, and proceeded for forty-three years until the last of his broadcasts on the BBC shortly before his death at his home in London in 1950. During this period, Stephens progressed from talented amateur to highly-regarded professional, from an un known essayist to a prominent writer, and from an author of printed works to a popular radio commentator. While his career progi-essed, his reputation as an artist increased to the point where he enjoyed the admiration ofW. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, George Moore and George Russell and where his abilities persuaded James Joyce to ask him to complete Finnegans Wake if Joyce could not do so. While these two volumes are by no means a complete collection of Stephens' prose, this is the first time his work has been collected in this way and the pieces are carefully chosen to demonstrate the development of his artistic craftmanship. Readers of this edition who may know Stephens as the beloved author of The Crock oJGold, The Charwoman's Daughter and other novels, can observe him in a variety of other roles: as political journalist, dramatist, speaker, critic, and storyteller. The editor Patricia A. McFate is President of the American-Scandinavian Foundation in New York. Her previous appointments have in cluded Deputy Chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Vice Provost of the University of Pennsylvania and she has taught at City College of New York, Northwestern University, and the Universities of Illinois and Pennsylvania. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

From Celtic Twilight to Revolutionary Dawn: the Irish Review, 1911-14

From Celtic Twilight to Revolutionary Dawn The Irish Review 1911-1914 By Ed Mulhall The July 1913 edition of The Irish Review , a monthly magazine of Irish Literature, Art and Science, leads off with an article " Ireland, Germany and the Next War" written under the pseudonym " Shan Van Vocht ". The article is a response to a major piece written by Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes books and a noted writer on international issues, in the Fortnightly Review of February 1903 called "Great Britain and the Next War". Shan Van Vocht takes issue with a central conclusion of Doyle's piece that Ireland's interests are one with Great Britain if Germany were to be victorious in any conflict. Doyle writes: "I would venture to say one word here to my Irish fellow- countrymen of all political persuasions. If they imagine that they can stand politically or economically while Britain falls, they are woefully mistaken. The British Fleet is their one shield. If it be broken, Ireland will go down. They may well throw themselves heartily into the common defense, for no sword can transfix England without the point reaching Ireland behind her." However The Irish Review author proposes to show that "Ireland, far from sharing the calamities that must necessarily fall on Great Britain from defeat by a Great Power, might conceivably thereby emerge into a position of much prosperity." The contents page of the July 1913 issue of The Irish Review In supporting this provocative stance the author initially tackles two aspects of the accepted British view of Ireland's fate under these circumstances: that Ireland would remain tied with Britain under German rule or that she might be annexed by the victor. -

James Stephens - Poems

Classic Poetry Series James Stephens - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive James Stephens(9 February 1882 - 26 December 1950) James Stephens was an Irish novelist and poet. James Stephens produced many retellings of Irish myths and fairy tales. His retellings are marked by a rare combination of humor and lyricism (Deirdre, and Irish Fairy Tales are often especially praise). He also wrote several original novels (Crock of Gold, Etched in Moonlight, Demi-Gods) based loosely on Irish fairy tales. "Crock of Gold," in particular, achieved enduring popularity and was reprinted frequently throughout the author's lifetime. Stephens began his career as a poet with the tutelage of "Æ" (<a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/george-william-a-e-russell-2/">George William Russel</a>l). His first book of poems, "Insurrections," was published during 1909. His last book, "Kings and the Moon" (1938), was also a volume of verse. During the 1930s, Stephens had some acquaintance with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/james-joyce/">James Joyce</a>, who found that they shared a birth year (and, Joyce mistakenly believed, a birthday). Joyce, who was concerned with his ability to finish what later became Finnegans Wake, proposed that Stephens assist him, with the authorship credited to JJ & S (James Joyce & Stephens, also a pun for the popular Irish whiskey made by John Jameson & Sons). The plan, however, was never implemented, as Joyce was able to complete the work on his own. During the last decade of his life, Stephens found a new audience through a series of broadcasts on the BBC. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles

Irish Communication Review Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 6 July 2020 Posters, Handkerchiefs and Murals: Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles Bradley Rohlf Mount Aloysius College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Commons, History of Gender Commons, Visual Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rohlf, Bradley (2020) "Posters, Handkerchiefs and Murals: Visual Gender Separation During the Troubles," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Irish Communications Review vol 17 (2020) Posters, handkerchiefs and murals: Visual gender separation during the Troubles Bradley Rohlf, Mount Aloysius College (Pennsylvania) Abstract The Troubles in Northern Ireland provide a complex and intriguing topic for many scholars in various academic disciplines. Their violence, publicity and tragedy are common themes that elicit a plethora of emotional responses throughout the world. However, the very intimate nature of this conflict creates a much more complex system of friends, foes and experiences for those involved. While the very heart of the Irish nationalist movement is founded on liberal and progressive concepts such as socialism and equality, the media associated with it sometimes promote tradition and conservatism, especially regarding gender. -

A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

THE ROLE OF THE GAELIC LEAGUE THOMAS MacDONAGH PATRICK PEARSE EOIN MacNEILL A League of extraordinary gentlemen Gaelic League was breeding ground for rebels, writes Richard McElligott EFLECTING on The Gaelic League was The Gaelic League quickly the rebellion that undoubtedly the formative turned into a powerful mass had given him nationalist organisation in the movement. By revitalising the his first taste of development of the revolutionary Irish language, the League military action, elite of 1916. also began to inspire a deep R Michael Collins With the rapid decline of sense of pride in Irish culture, lamented that the Easter Rising native Irish speakers in the heritage and identity. Its wide was hardly the “appropriate aftermath of the Famine, many and energetic programme of time for memoranda couched sensed the damage would be meetings, dances and festivals in poetic phrases, or actions irreversible unless it was halted injected a new life and colour DOUGLAS HYDE worked out in similar fashion”. immediately. In November 1892, into the often depressing This assessment encapsulates the Gaelic scholar Douglas Hyde monotony of provincial Ireland. the generational gulf between delivered a speech entitled ‘The Another significant factor participation in Gaelic games. cursed their memory”. Pearse the romantic idealism of the Necessity for de-Anglicising for its popularity was its Within 15 years the League had was prominent in the League’s revolutionaries of 1916 and the Ireland’. Hyde pleaded with his cross-gender appeal. The 671 registered branches. successful campaign to get Irish military efficiency of those who fellow countrymen to turn away League actively encouraged Hyde had insisted that the included as a compulsory subject would successfully lead the Irish from the encroaching dominance female participation and one Gaelic League should be strictly in the national school system. -

James Stephens at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 5 Issue 9 March Article 5 March 1961 James Stephens at Colby College Richard Cary. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 5, no.9, March 1961, p.224-253 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Cary.: James Stephens at Colby College 224 Colby Library Quarterly shadow and symbolize death: the ship sailing to the North Pole is the Vehicle of Death, and the captain of the ship is Death himself. Stephens here makes use of traditional motifs. for the purpose of creating a psychological study. These stories are no doubt an attempt at something quite distinct from what actually came to absorb his mind - Irish saga material. It may to my mind be regretted that he did not write more short stories of the same kind as the ones in Etched in Moonlight, the most poignant of which is "Hunger," a starvation story, the tragedy of which is intensified by the lucid, objective style. Unfortunately the scope of this article does not allow a treat ment of the rest of Stephens' work, which I hope to discuss in another essay. I have here dealt with some aspects of the two middle periods of his career, and tried to give significant glimpses of his life in Paris, and his .subsequent years in Dublin. In 1915 he left wartime Paris to return to a revolutionary Dub lin, and in 1925 he left an Ireland suffering from the after effects of the Civil War. -

A Poet's Rising

A POET’S RISING A POET’S RISING In 2015 the Irish Writers Centre answered the Arts Council’s Open Call for 2016 and A Poet’s Rising was born. Our idea was this: to commission six of Ireland’s most eminent poets to respond through poetry focusing on a key historical figure and a particular location associated with the Rising. The poets would then be filmed in each discreet location and made permanent by way of an app, freely available for download. The resulting poems are beautiful, important works that deserve to be at the forefront of the wealth of artistic responses generated during this significant year in Ireland’s history. We are particularly proud to be producing this exceptional oeuvre in the year of our own 25th anniversary since the opening of the Irish Writers Centre. • James Connolly at Liberty Hall poem by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin • Pádraig Pearse in the GPO poem by Paul Muldoon • Kathleen Lynn in City Hall poem by Jessica Traynor • The Ó Rathaille at O’Rahilly Parade poem by Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill • Elizabeth O’Farrell in Moore Lane poem by Theo Dorgan • The Fallen at the Garden of Remembrance poem by Thomas McCarthy We wish to thank Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Paul Muldoon, Jessica Traynor, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Theo Dorgan and Thomas McCarthy for agreeing to take part and for their resonant contributions, and to Conor Kostick for writing the historical context links between each poem featured on the app. A special thanks goes to Colm Mac Con Iomaire, who has composed a beautiful and emotive score, entitled ‘Solasta’, featured throughout the app. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters.