ARSC Journal Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS ROYAL LIVERPOOL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA ANDREW MANZE Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 –1958)

A LONDON SYMPHONY SYMPHONY NO. 8 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS ROYAL LIVERPOOL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA ANDREW MANZE Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 –1958) Symphony No.2 in G ‘A London Symphony’ 1. I. Lento – Allegro risoluto (molto pesante) 14.29 2. II. Lento 10.59 3. III. Scherzo (Nocturne): Allegro vivace 7.55 4. IV. Andante con moto – Maestoso alla Marcia (quasi lento) – Allegro – 13.19 Maestoso alla Marcia (alla I) – Epilogue (Andante sostenuto) Symphony No.8 in D minor 5. I. Fantasia (Variazioni senza tema) 10.47 6. II. Scherzo alla marcia (per strumenti a fiato): Allegro alla marcia 3.50 7. III. Cavatina (per strumenti ad arco): Lento espressivo 9.03 8. IV. Toccata: Moderato maestoso 5.06 Total timing: 75.33 ROYAL LIVERPOOL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA ANDREW MANZE CONDUCTOR 2 SYMPHONIES EARLY AND LATE a kind of spiritual and musical summation; we have come full circle, evoking the silent river’s inexorable flow and the veiling mists as metaphors for some profound spiritual truth. At Symphony No.2 ‘A London Symphony’ the very end a muted violin plays a last soaring reminiscence of the theme over soft strings. The two or three years immediately before the outbreak of the Great War were a high point Muted cornets, trumpets and horns sound a soft chord and then, like the sun breaking for British music, when the music of a new generation of younger composers was beginning through, the brass all remove their mutes for the final chord. to appear on concert programmes. Slightly older than the rest, Vaughan Williams was already known for On Wenlock Edge , A Sea Symphony and the Tallis Fantasia , and in March 1914 his Towards the end of his life Vaughan Williams cited H.G. -

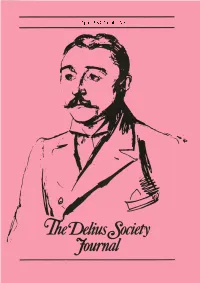

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

In Concert AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 2012

ABOUT THE MUSIC GRIEG CONCERTO /IN CONCERT AUGUST–SEPTEMBER 2012 GRIEG CONCERTO 30 AUGUST–1 SEPTEMBER STEPHEN HOUGH PLAYS TCHAIKOVSKY 14, 15 AND 17 SEPTEMBER TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE 20–22 SEPTEMBER ENIGMA VARIATIONS 28 SEPTEMBER MEET YOUR MSO MUSICIANS: SYLVIA HOSKING AND MICHAEL PISANI PIERS LANE VISITS GRIEG’S BIRTHPLACE STEPHEN HOUGH ON TCHAIKOVSKY’S PIANO CONCERTO NO.2 SIR ANDREW DAVIS HAILS THE NEW HAMER HALL twitter.com/melbsymphony facebook.com/melbournesymphony IMAGE: SIR ANDREW Davis CONDUCTING THE MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Download our free app 1 from the MSO website. www.mso.com.au/msolearn THE SPONSORS PRINCIPAL PARTNER MSO AMBASSADOR Geoffrey Rush GOVERNMENT PARTNERS MAESTRO PARTNER CONCERTMASTER PARTNERS MSO POPS SERIES REGIONAL TOURING PRESENTING PARTNER PARTNER ASSOCIATE PARTNERS SUPPORTING PARTNERS MONASH SERIES PARTNER SUPPLIERS Kent Moving and Storage Quince’s Scenicruisers Melbourne Brass and Woodwind Nose to Tail WELCOME Ashton Raggatt McDougall, has (I urge you to read his reflections been reported all over the world. on Grieg’s Concerto on page 16) and Stephen Hough, and The program of music by Grieg conductors Andrew Litton and and his friend and champion HY Christopher Seaman, the last of Percy Grainger that I have the whom will be joined by two of the privilege to conduct from August finest brass soloists in the world, otograp 29 to September 1 will be a H P Radovan Vlatkovic (horn) and wonderful opportunity for you to ta S Øystein Baadsvik (tuba), for our O experience all the richness our C special Town Hall concert at the A “new” hall has to offer. -

'Koanga' and Its Libretto William Randel Music & Letters, Vol. 52, No

'Koanga' and Its Libretto William Randel Music & Letters, Vol. 52, No. 2. (Apr., 1971), pp. 141-156. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0027-4224%28197104%2952%3A2%3C141%3A%27AIL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B Music & Letters is currently published by Oxford University Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oup.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 22 12:08:38 2007 'KOANGA' AND ITS LIBRETTO FREDERICKDELIUS arrived in the United States in 1884, four years after 'The Grandissimes' was issued as a book, following its serial run in Scribner's Monthh. -

Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924

Wickstead, H 2017 “Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 27(1): 4, pp. 1–18, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bha-596 RESEARCH PAPER “Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924 Helen Wickstead Histories of archaeology traditionally traced the progress of the modern discipline as the triumph of secular disenchanted science over pre-modern, enchanted, world-views. In this article I complicate and qualify the themes of disenchantment and enchantment in archaeological histories, presenting an analysis of how both contributed to the development of scientific theory and method in the earliest decades of the twentieth century. I examine the interlinked biographies of a group who created a joke religion called “The Cult of Kata”. The self-described “Kataric Circle” included notable archaeologists Harold Peake, O.G.S. Crawford and Richard Lowe Thompson, alongside classicists, musicians, writers and performing artists. The cult highlights the connections between archaeology, theories of performance and the performing arts – in particular theatre, music, folk dance and song. “Wild worship” was linked to the consolidation of collectivities facilitating a wide variety of scientific and artistic projects whose objectives were all connected to dreams of a future utopia. The cult parodied archaeological ideas and methodologies, but also supported and expanded the development of field survey, mapping and the interpretation of archaeological distribution maps. The history of the Cult of Kata shows how taking account of the unorthodox and the interdisciplinary, the humorous and the recreational, is important within generously framed approaches to histories of the archaeological imagination. -

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

Whitman 1 Walt Whitman (1819-1892) 2 Section headings and information Poems 6 “In Cabin’d Ships at Sea” 7 “We Two, How Long We Were Foole’d” 8 “These I Singing in Spring” 9 “France, the 18th Year of These States” 10 “Year of Meteors (1859-1860)” 11 “Song for All Seas, All Ships” 12 “Gods” 13 “Beat! Beat! Drums!” 14 “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field one Night” 15 “A March in the Ranks Hard-Prest, and the Road Unknown” 16 “O Captain! My Captain!” 17 “Unnamed Lands” 18 “Warble for Lilac-Time” 19 “Vocalism” 20 “Miracles” 21 “An Old Man’s Thought of School” 22 “Thou Orb Aloft Full-Dazzling” 23 “To a Locomotive in Winter” 24 “O Magnet-South” 25 “Years of the Modern” Source: Leaves of Grass. Sculley Bradley and Harold W. Blodgett, ed. NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1973. Print. Note: For the IOC, copies of the poems will contain no information other than the title, the poem’s text, and line numbers. Whitman 2 Leaves of Grass, 1881, section headings for those poems within this packet WW: Walt Whitman LG: Leaves of Grass MS: manuscript “Inscriptions” First became a group title for the opening nine poems of LG 1871. In LG 1881 the group was increased to the present twenty-four poems, of which one was new. “Children of Adam” In two of his notes toward poems WW set forth his ideas for this group. One reads: “A strong of Poems (short, etc.), embodying the amative love of woman—the same as Live Oak Leaves do the passion of friendship for man.” (MS unlocated, N and F, 169, No. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

DELIUS BOOKLET:Bob.Qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1

DELIUS BOOKLET:bob.qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1 second piece, Summer Night on the River, is equally evocative, this time suggested by the river Loing that lay at the the story of a voodoo prince sold into slavery, based on an episode in the novel The Grandissimes by the American bottom of Delius’s garden near Fontainebleau, the kind of scene that might have been painted by some of the French writer George Washington Cable. The wedding dance La Calinda was originally a dance of some violence, leading to painters that were his contemporaries. hysteria and therefore banned. In the Florida Suite and again in Koanga it lacks anything of its original character. The opera Irmelin, written between 1890 and 1892, and the first attempt by Delius at the form, had no staged Koanga, a lyric drama in a prologue and three acts, was first heard in an incomplete concert performance at St performance until 1953, when Beecham arranged its production in Oxford. The libretto, by Delius himself, deals with James’s Hall in 1899. It was first staged at Elberfeld in 1904. With a libretto by Delius and Charles F. Keary, the plot The Best of two elements, Princess Irmelin and her suitors, none of whom please her, and the swine-herd who eventually wins is set on an eighteenth century Louisiana plantation, where the slave-girl Palmyra is the object of the attentions of her heart. The Prelude, designed as an entr’acte for the later opera Koanga, makes use of four themes from Irmelin. -

A Village Romeo and Juliet the Song of the High Hills Irmelin Prelude

110982-83bk Delius 14/6/04 11:00 am Page 8 Also available on Naxos Great Conductors • Beecham ADD 8.110982-83 DELIUS A Village Romeo and Juliet The Song of the High Hills Irmelin Prelude Dowling • Sharp • Ritchie Soames • Bond • Dyer Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Sir Thomas Beecham Naxos Radio (Recorded 1946–1952) Over 50 Channels of Classical Music • Jazz, Folk/World, Nostalgia Accessible Anywhere, Anytime • Near-CD Quality www.naxosradio.com 2 CDs 8.110982-83 8 110982-83bk Delius 14/6/04 11:00 am Page 2 Frederick Delius (1862-1934) 5 Koanga: Final Scene 9:07 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra • Sir Thomas Beecham (1879-1961) (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus) Recorded on 26th January, 1951 Delians and Beecham enthusiasts will probably annotation, frequently content with just the notes. A Matrix Nos. CAX 11022-3, 11023-2B continue for ever to debate the relative merits of the score of a work by Delius marked by Beecham, First issued on Columbia LX 1502 earlier recordings made by the conductor in the 1930s, however, tells a different story, instantly revealing a mostly with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, in most sympathetically engaged music editor at work. comparison with those of the 1940s and 1950s Pulse, dynamics, phrasing, expressive nuance and All recordings made in Studio 1, Abbey Road, London recorded with handpicked players of the Royal articulation, together with an acute sensitivity to Transfers & Production: David Lennick Philharmonic Orchestra. Following these two major constantly changing orchestral balance, are annotated Digital Noise Reduction: K&A Productions Ltd. periods of activity, the famous EMI stereo remakes with painstaking practical detail to compliment what Original recordings from the collections of David Lennick, Douglas Lloyd and Claude G. -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2001, Number 129 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students £10 per year US/\ and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Aust1alasia and far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Lionel Carley 131\, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon l Iandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard I Iickox FRCO (CHM) Lyndon Jenkins Tasmin Little f CSM, ARCM (I Ions), I Jon D. Lilt, DipCSM Si1 Charles Mackerras CBE Rodney Meadows Robc1 t Threlfall Chain11a11 Roge1 J. Buckley Trcaswc1 a11d M11111/Jrrship Src!l'taiy Stewart Winstanley Windmill Ridge, 82 Jlighgate Road, Walsall, WSl 3JA Tel: 01922 633115 Email: delius(alukonlinc.co.uk Serirta1y Squadron Lcade1 Anthony Lindsey l The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex P021 3SR 'fol: 01243 824964 Editor Jane Armour-Chclu 17 Forest Close, Shawbirch, 'IC!ford, Shropshire TFS OLA Tel: 01952 408726 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.dclius.org.uk Emnil: [email protected]. uk ISSN-0306-0373 Ch<lit man's Message............................................................................... 5 Edilot ial....................... .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... 6 ARTICLES BJigg Fair, by Robert Matthew Walker................................................ 7 Frede1ick Delius and Alf1cd Sisley, by Ray Inkslcr........... .................. 30 Limpsficld Revisited, by Stewart Winstanley....................................... 35 A Forgotten Ballet ?, by Jane Armour-Chclu -

Beecham: the Delius Repertoire - Part Three by Stephen Lloyd 13

April 1983, Number 79 The Delius Society Journal The DeliusDe/ius Society Journal + .---- April 1983, Number 79 The Delius Society Full Membership £8.00t8.00 per year Students £5.0095.00 Subscription to Libraries (Journal only) £6.00f,6.00 per year USA and Canada US $17.00 per year President Eric Fenby OBE, Hon DMus,D Mus,Hon DLitt,D Litt, Hon RAM Vice Presidents The Rt Hon Lord Boothby KBE, LLD Felix Aprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson M Sc, Ph D (Founder Member) Sir Charles Groves CBE Stanford Robinson OBE, ARCM (Hon), Hon CSM Meredith Davies MA, BMus,B Mus,FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE, Hon DMusD Mus VemonVernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) ChairmanChairmart RBR B Meadows 5 Westbourne House, Mount Park Road, Harrow, Middlesex Treasurer Peter Lyons 160 Wishing Tree Road, S1.St. Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex Secretary Miss Diane Eastwood 28 Emscote Street South, Bell Hall, Halifax, Yorkshire Tel: (0422) 5053750537 Membership Secretary Miss Estelle Palmley 22 Kingsbury Road, Colindale,Cotindale,London NW9 ORR Editor Stephen Lloyd 414l Marlborough Road, Luton, Bedfordshire LU3 lEFIEF Tel: Luton (0582)(0582\ 20075 2 CONTENTS Editorial...Editorial.. 3 Music Review ... 6 Jelka Delius: a talk by Eric Fenby 7 Beecham: The Delius Repertoire - Part Three by Stephen Lloyd 13 Gordon Clinton: a Midlands Branch meeting 20 Correspondence 22 Forthcoming Events 23 Acknowledgements The cover illustration is an early sketch of Delius by Edvard Munch reproduced by kind permission of the Curator of the Munch Museum, Oslo. The quotation from In a Summer GardenGuden on page 7 is in the arrangement by Philip Heseltine included in the volume of four piano transcriptions reviewed in this issue and appears with acknowledgement to Thames Publishing and the Delius Trust.