(Up) Against the (In) Between: Interstitial Spatiality in Genet and Derrida Clare Blackburne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jean Genet Ebook

JEAN GENET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Bradby | 214 pages | 17 Feb 2012 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415375061 | English | London, United Kingdom Jean Genet PDF Book Hayman, Ronald. His obituary ran in the New York Times, April 16, The word is recorded from… Ecological genetics , ecological genetics The study of genetics with particular reference to variation on a global and local geographic scale. To achieve harmony in bad taste is the height of elegance. His heart leaned from his "'religious nature" as he confessed in his autobiographical Thief's Journal , English Restrictions apply. They appear fleetingly and are downtrodden, when not hysterics or madams. He would be reborn as a witness for the Palestinians. Genet: A Collection of Critical Essays. In the longest section of the speech, Genet discusses the new forms of solidarity that he believes are possible between whites and Blacks in America, and the difficulties involved in convincing white people of their necessity. To be granted, from his pen, the status of a real mother, a woman had to be Arab or black. Driver, Jean Genet ; Richard N. But there was a more elusive figure, still admired today by artists like Patti Smith , who influenced and challenged their thinking: poet, playwright, novelist, film director, and pardoned convict Jean Genet. She loathes Madame and criticizes her gifts, including the fur, which she took back. But the carpenter's family that was entrusted with his care gave Genet ample attention and affection. With this play Genet was established as an outstanding figure in the Theatre of the Absurd. Solange promises never to abandon her. -

Choreographies: Jacques Derrida and Christie V. Mcdonald Author(S)

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 141.225.218.75 on Mon, 27 Apr 2015 09:11:22 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions INTERVIEW CHOREOG RAPH IES ................... JACQUESDERRIDA and CHRISTIEV. MCDONALD MEE-5_- 44~-i~il"':?ii':iiiii ":-:---iii-i Question I' MCDONALD:Emma Goldman, a maverickfeminist from the late nine- teenth century,once said of the feministmovement: "If I can'tdance I don't wantto be partof yourrevolution." Jacques Derrida, you havewritten about the question of woman and what it is that constitutes 'the feminine.' In Spurs/Eperons(Chicago and London:The Universityof ChicagoPress, 1978), a textdevoted to Nietzsche,style and woman,you wrotethat "that which will not be pinneddown by truth[truth?] is, in truth,feminine." And you warnedthat such a proposition"should not... be hastilymistaken for a woman'sfeminin- ity, for female sexuality,or for any other of those essentializingfetishes which . :-?i- .l . .... mightstill tantalize the dogmaticphilosopher, the impotentartist or the inexpe- riencedseducer who has not yet escaped his foolishhopes of capture." Whatseems to be at playas you take up Heidegger'sreading of Nietzsche is whether or not sexual differenceis a "regionalquestion in a largerorder which would subordinateit firstto the domain of general ontology, subse- ....... -

Jean Genet’S the Maids Translated by Bernard Frechtman Directed by Stephanie Shroyer Sept

JEAN GENET’S THE MAIDS TRANSLATED BY BERNARD FRECHTMAN DIRECTED BY STEPHANIE SHROYER SEPT. 18 – NOV. 12, 2016 Study Guides from A Noise Within A rich resource for teachers of English, reading arts, and drama education. Dear Reader, We’re delighted you’re interested in our study guides, designed to provide a full range of information on our plays to teachers of all grade levels. A Noise Within’s study guides include: • General information about the play (characters, synopsis, timeline, and more) • Playwright biography and literary analysis • Historical content of the play • Scholarly articles • Production information (costumes, lights, direction, etc.) • Suggested classroom activities • Related resources (videos, books, etc.) • Discussion themes • Background on verse and prose (for Shakespeare’s plays) Our study guides allow you to review and share information with students to enhance both lesson plans and pupils’ theatrical experience and appreciation. They are designed to let you extrapolate articles and other information that best align with your own curricula and pedagogic goals. More information? It would be our pleasure. We’re here to make your students’ learning experience as rewarding and memorable as it can be! All the best, Alicia Green Pictured: Deborah Strang, The Tempest, 2014. PHOTO BY CRAIG SCHWARTZ. DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION TABLE OF CONTENTS The Maids Character List ............................................4 Synopsis .........................................................5 Playwright Biography: Jean Genet .....................................6 -

What Remains of the "Between" and of the Space That Divides, the Seam That Touches Both Borders? Between Literature and Philosophy? Between Texts and Readers? Between

1 What remains? What remains of the "between" and of the space that divides, the seam that touches both borders? Between literature and philosophy? Between texts and readers? Between Glas and CA?1 "What remains of the 'remain(s)' when it is pulled to pieces, torn into morsels? Where does the rule of its being torn into morsels come from? Must one still try to determine a regularity when tearing to pieces what remains of the remain(s)? A strictly angular question. The remain(s) here suspends itself. Let us give ourselves the time of this suspense. For the moment time will be nothing but the suspense between the regularity and the irregularity of the morsels of what remains."(Glas, 226a) There are too many questions remaining. But how, precisely, is that possible? How do they "remain?" What "past" do they mark as "remains?" How does one deal with remains? What is the work of mourning and interrment, the glas-work, the work announced even as it is made impossible by Glas? Can this be the mark of a reading? A Writing? A "critical discourse?" What is it, finally, "to remain?" This is the fundamental (post)-ontological question that Glas ceaselessly recites even as it tears the fabric of such a question, the texts that appear to posit it (the texts of Sa, the Phenomenology of Spirit), and those that disseminate it through a celebration of the partial and the signature (the texts of the thief, the prisoner, the homosexual) into pieces. In approaching these questions of what can (possibly) remain, Glas continually reminds me that the number most often written into Sa, the Hegelian number parexcellence , is three. -

SPECTRES of a CRISIS: READING JACQUES DERRIDA AFTER the GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS of 2008 by JOHN JAMES FRANCIS a Thesis Submi

SPECTRES OF A CRISIS: READING JACQUES DERRIDA AFTER THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS OF 2008 by JOHN JAMES FRANCIS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Culture, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham JUNE 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis investigates a theoretical response to the question of what constitutes the political implications of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This thesis, working within the tradition of critical and cultural theory, undertakes a sustained engagement with the works of Jacques Derrida to theorise the traditions, norms, and practices that inform a response to an event such as the crisis of 2008. This thesis works with his proposals that: the spectre of its limitations haunts politics; that this has led to the ‘deconstruction’ of the meaning of politics through complex textual frameworks; and that this dynamic leads to a tension between the arrival of new political possibilities on the one hand and new forms of political sovereignty on the other. -

Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor

Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in the Department of French, the School of Music, and Cultural, Social, and Political Thought Mitch Renaud, 2015 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 Supervisory Committee Emile Fromet de Rosnay, Department of French and CSPT Supervisor Christopher Butterfield, School of Music Co-Supervisor Stephen Ross, Department of English and CSPT Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Emile Fromet de Rosnay (Department of French and CSPT) Supervisor Christopher Butterfield (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Stephen Ross (Department of English and CSPT) Outside Member Noise is noisy. Its multiple definitions cover one another in such a way as to generate what they seek to describe. My thesis tracks the ways in which noise can be understood historically and theoretically. I begin with the Skandalkonzert that took place in Vienna in 1913. I then extend this historical example into a theoretical reading of the noise of Derrida’s Of Grammatology, arguing that sound and noise are the unheard of his text, and that Derrida’s thought allows us to hear sound studies differently. Writing on sound must listen to the noise of the motion of différance, acknowledge the failings, fading, and flailings of sonic discourse, and so keep in play the aporias that constitute the field of sound itself. -

Jacques Derrida MAR G in S of Philosophy

Jacques Derrida MAR G IN S of Philosophy rranslated, with Additional Notes, by Alan Bass The( · University of Chicago Press Contents Jacques Derrida teaches the history of philosophy at the Ecole normale superieure, Paris. Four of his other �orks Translator's Note vii have been published by the University of Chicago Press · Tympan ix in English translation: Writing and Difference (1978); Spurs: Nietzsche's Styles Eperons: Les styles de Nietzsche (bilingual Differance 1 edition, 1979); PositionsI (1981); and Dissemination (1981). Ousia and Gramme: Note on a Note from Being and Time 29 The Pit and the Pyramid: Introduction to Hegel's Semiology 69 The Ends of Man 109 The Linguistic Circle of Geneva 137 Form and Meaning: A Note Y.on the Phenomenology of Language 155 The Supplement of Copula: Philosophy before Linguistics 175 White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy 207 The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Qual Quelle: The Harvester Press Limited, Brighton, Sussex Valery's Sources 273 1982 by The University of Chicago Signature Event Context 307 All© rights reserved. Published 1982 Printed in the United States of America 89 88 87 86 85 84 83 82 5 4 3 2 1 This work was published in Paris under the title Marges de Ia philosophie, 1972, by Les Editions de Minuit. Libraryof Congress© Cataloging in Publication Data Derrida, Jacques. Margins of philosophy. Title. I82-11137. v rranslatorIs Note Many of these essays have been translated before. Although all the translations in this volume are "new" and "my own" -the quotation marks serving here, as Derrida might say, as an adequate precaution-! have been greatly assisted in my work by consulting: "Differance," trans. -

Jacques Derrida Law As Absolute Hospitality

JACQUES DERRIDA LAW AS ABSOLUTE HOSPITALITY JACQUES DE VILLE NOMIKOI CRITICAL LEGAL THINKERS Jacques Derrida Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality presents a comprehensive account and understanding of Derrida’s approach to law and justice. Through a detailed reading of Derrida’s texts, Jacques de Ville contends that it is only by way of Derrida’s deconstruction of the metaphysics of presence, and specifi cally in relation to the texts of Husserl, Levinas, Freud and Heidegger, that the reasoning behind his elusive works on law and justice can be grasped. Through detailed readings of texts such as ‘To Speculate – on Freud’, Adieu, ‘Declarations of Independence’, ‘Before the Law’, ‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, Given Time, ‘Force of Law’ and Specters of Marx, de Ville contends that there is a continuity in Derrida’s thinking, and rejects the idea of an ‘ethical turn’. Derrida is shown to be neither a postmodernist nor a political liberal, but a radical revolutionary. De Ville also controversially contends that justice in Derrida’s thinking must be radically distinguished from Levinas’s refl ections on ‘the Other’. It is the notion of absolute hospitality – which Derrida derives from Levinas, but radically transforms – that provides the basis of this argument. Justice must, on de Ville’s reading, be understood in terms of a demand of absolute hospitality which is imposed on both the individual and the collective subject. A much needed account of Derrida’s infl uential approach to law, Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality will be an invaluable resource for those with an interest in legal theory, and for those with an interest in the ethics and politics of deconstruction. -

Styling Against Absolute Knowledge in Derrida's Glas Jessica Marian

parrhesia 24 · 2015 · 217-238 styling against absolute knowledge in derrida's glas jessica marian Jacques Derrida’s Glas (1974) is written entirely across two parallel columns, the left column focussing on a reading of selected works by the G. W. F. Hegel, the nineteenth-century philosopher of what Derrida will refer to as ‘savoir absolu’ (absolute knowledge), and the other column, on the right, concentrating on a selection of the fiction and plays of Jean Genet, one of France’s most avowedly marginal authors, a self-confessed “traitor, thief, informer, coward and queer.”1 Glas is one of Derrida’s most stylistically experimental texts, disregarding linear argumentation and citation standards in favour of an approach which draws upon such elements as word-play, aural resonances and textual interruptions or supplements referred to as “judases”. Glas is regularly grouped with Éperons: les styles de Nietzsche (1978) and La Carte postale: de Socrate à Freud et au-delà (1980) as roughly contemporaneous texts written in a non-traditional, somewhat literary style. In his 1980 thesis defence, Derrida located this group of three works within a “continued pursuit […] of the project of grammatology”, “an expansion of earlier attempts”, whilst also alluding towards a felt need to attempt to develop a different style and performance of writing which would turn “towards textual configurations that were less and less linear, logical and topical forms, even typographical forms that were more daring, the intersection of corpora, mixtures of genera or of modes, changes of tone […], satire, rerouting, grafting, etc.”2 In this paper I read Glas with an eye towards exploring precisely this linkage between Derrida’s philosophical project and Glas’ highly experimental style—I argue that Glas’ style is intimately linked with its philosophical project. -

Read the Introduction

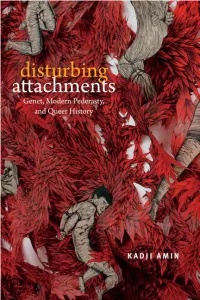

disturbing attachments A series edited by Lauren Berlant and Lee Edelman disturbing attachments Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History KADJI AMIN Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Names: Amin, Kadji, [date– ] author. Title: Disturbing attachments [electronic resource] : Genet, modern pederasty, and queer history / Kadji Amin. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Series: Theory Q | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017009234 (print) | lccn 2017015463 (ebook) isbn 9780822368892 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369172 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822372592 (e-book) Subjects: lcsh: Genet, Jean, 1910–1986. | Homosexuality in literature. | Queer theory. Classification: lcc pq2613.e53 (ebook) | lcc pq2613.e53 z539 2017 (print) | ddc 842/.912—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009234 Cover art: Felipe Baeza, Fogata, 2013. Woodblock, silkscreen, and monoprint on varnished paper. Courtesy of the artist. contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS · ix INTRODUCTION · 1 CHAPTER 1 · 19 Attachment Genealogies of Pederastic Modernity CHAPTER 2 · 45 Light of a Dead Star: The Nostalgic Modernity of Prison Pederasty CHAPTER 3 · 76 Racial Fetishism, Gay Liberation, and the Temporalities of the Erotic CHAPTER 4 · 109 Pederastic Kinship CHAPTER 5 · 141 Enemies of the State: Terrorism, Violence, and the Affective Politics of Transnational Coalition EPILOGUE · 176 Haunted by the 1990s: Queer Theory’s Affective Histories NOTES · 191 BIBLIOGRAPHY · 235 INDEX · 249 Solange: S’aimer dans le dégoût, ce n’est pas s’aimer. -

Jacques Derrida Dissemination Translated, with an Introduction

Jacques Derrida Dissemination Translated, with an Introduction and Additional Notes, by Barbara Johnson The University of Chicago Press Contents Translator's Introduction VlI Outwork, prefacing 1 Plato's Pharmacy 61 I 65 1. Pharmacia 65 2. The Father of Logos 75 3. The Filial Inscription: Theuth, Hermes, Thoth, Nabfr, Nebo 84 4. The Pharmakon 95 5. The 'pharmakeus 117 II lW 6. The Pharmakos 128 7. The Ingredients: Phantasms, Festivals, and Paints 134 8. The Heritage of the Pharmakon: Family Scene 142 9. Play: From the Pharmakon to the Letter and from Blindness to the Supplement 156 The Double Session 173 I 175 II 227 VI CONTENTS Dissemination 287 I 289 1. The Trigger 290 2. The Apparatus or Frame 296 3. The Scission 300 4. The Double Bottom of the Plupresent 306 5. wriTing, encAsIng, screeNing 313 6. The Attending Discourse 324 II 330 7. The Time before First 330 8. The Column 340 9. The Crossroads of the "Est" 347 10. Grafts, a Return to Overcasting 355 XI. The Supernumerary 359 Translator's Introduction All translation is only a somewhat provisional way of coming to terms with the foreignness of languages. -Walter Benjamin, "The Task of the Translator" What is translation? On a platter A poet's pale and glaring head, A parrot's screech, a monkey's chatter, And profanation of the dead. -Vladimir Nabokov, "On Translating 'Eugene Onegin'" Jacques Derrida, born in Algiers in 1930, teaches philosophy at the Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris. His tremendous impact on contemporary theoretical thought began in 1967 with the simultaneous publication -

The Ecstasy of Rebellion in the Works of Jean Genet

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Dissidence is Bliss: The Ecstasy of Rebellion in the Works of Jean Genet Shane Fallon CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/237 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Dissidence is Bliss: The Ecstasy of Rebellion in the Works of Jean Genet By Shane Fallon Mentored by Harold Aram Veeser August 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts of the City College of the City University of New York “We must see our rituals for what they are: completely arbitrary things, tired of games and irony, it is good to be dirty and bearded, to have long hair, to look like a girl when one is a boy (and vice versa); one must put ‘in play,’ show up transform, and reverse the systems which quietly order us about. As far as I am concerned, that is what I try to do in my work.” -Michel Foucault “What is this story of Fantine about? It is about society buying a slave. From whom? From misery. From hunger, from cold, from loneliness, from desertion, from privation. Melancholy barter. A soul for a piece of bread. Misery makes the offer, society accepts.” -Victor Hugo, Les Miserables Table of Contents Introduction…….