Old Themes for New Times: Basildon Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxism Today: the Forgotten Visionaries Whose Ideas Could Save Labour John Harris Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Marxism Today: the forgotten visionaries whose ideas could save Labour John Harris Tuesday, 29 September 2015 The best guide to politics in 2015 is a magazine that published its final issue more than two decades ago A selection of Marxism Today’s greatest covers. Composite: Amiel Melburn Trust In May 1988, a group of around 20 writers and academics spent a weekend at Wortley Hall, a country house north of Sheffield, loudly debating British politics and the state of the world. All drawn from the political left, by that point they were long used to defeat, chiefly at the hands of Margaret Thatcher. Now, they were set on figuring out not just how to reverse the political tide, but something much more ambitious: in essence, how to leave the 20th century. Over the previous decade, some of these people had shone light on why Britain had moved so far to the right, and why the left had become so weak. But as one of them later put it, they now wanted to focus on “how society was changing, what globalisation was about – where things were moving in a much, much deeper sense”. The conversations were not always easy; there were raised voices, and sometimes awkward silences. Everything was taped, and voluminous notes were taken. A couple of months on, one of the organisers wrote that proceedings had been “part coherent, part incoherent, exciting and frustrating in just about equal measure”. What emerged from the debates and discussions was an array of amazingly prescient insights, published in a visionary magazine called Marxism Today. -

Welsh Communist Party) Papers (GB 0210 PEARCE)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Bert Pearce (Welsh Communist Party) Papers (GB 0210 PEARCE) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH This description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) Second Edition; AACR2; and LCSH. https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/bert-pearce-welsh-communist-party- papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/bert-pearce-welsh-communist-party-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Bert Pearce (Welsh Communist Party) Papers Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CommonKnowledge Pacific University CommonKnowledge Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work Faculty Scholarship (CAS) 2017 New Times: Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism Christopher D. Wilkes Pacific University Recommended Citation Wilkes, Christopher D., "New Times: Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism" (2017). Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work. 4. https://commons.pacificu.edu/sasw/4 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship (CAS) at CommonKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work by an authorized administrator of CommonKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Times: Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism Description 'Stuart Hall and the Culturalist Turn' is an extended version of Chapter Five from 'The State: a Biography', forthcoming, from Cambridge Scholars Press. Rights Terms of use for work posted in CommonKnowledge. This book chapter is available at CommonKnowledge: https://commons.pacificu.edu/sasw/4 New Times Stuart Hall, Culturalism, Fordism and Post-Fordism Introduction : the Winter of Discontent and the Rise of Thatcherism. In 1979, the year of Poulantzas’s death, and in the wake of a disastrous period of Labour rule in Britain, Margaret Thatcher came to power as the first woman Prime Minister in U.K. history, and with a platform of reforms in hand that was to change the nature of British politics for decades to come. This new régime, rapidly labelled Thatcherism, sought to deal with major problems of unemployment and a long-standing economic crisis. -

Industrial Militancy, Reform and the 1970S: a Review of Recent Contributions to CPGB Historiography

FJHP Volume 23 (2006) Industrial Militancy, Reform and the 1970s: A Review of Recent Contributions to CPGB Historiography Evan Smith Flinders University The historiography of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) has grown rapidly since its demise in 1991 and has created much debate for a Party seen as only of marginal interest during its actual existence. Since 1991, there have been four single volume histories of the Party, alongside the completion of the ‘official’ history published by Lawrence & Wishart and several other specialist studies, adding to a number of works that existed before the Party’s collapse. In recent years, much of the debate on Communist Party historiography has centred on the Party and its relationship with the Soviet Union. This is an important area of research and debate as throughout the period from the Party’s inception in 1920 to the dissolution of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1943 (and even beyond), the shadow of the Soviet Union stood over the CPGB. However an area that has been overlooked in comparison with the Party in the inter-war era is the transitional period when the CPGB went from being an influential part of the trade union movement to a Party that had been wrought by internal divisions, declining membership and a lowering industrial support base as well as threatened, alongside the entire left, by the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979. This period of CPGB history, roughly from 1973 to 1979, was heavily influenced by the rise of Gramscism and Eurocommunism, in which a significant portion of the Party openly advocated reforms and a shift away from an emphasis of industrial militancy. -

Against Trotskyism

INSTITUTE OF MARXISM-LENINISM OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE CPSU AGAINST TROTSKYISM THE STRUGGLE OF LENIN AND THE CPSU AGAINST TROTSKYISM A Collection of Documents PROGRESS PUBLISHERS Moscow PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The works of Lenin (in their entirety or extracts) and the decisions adopted at congresses and conferences of the Bolshevik Party and at plenary meetings of the CC offered in this volume show that Trotskyism is an anti-Marxist, opportunist trend, show its subversive activities against the Communist Party and expose its ties with the opportunist leaders of the Second International and with revisionist, anti-Soviet trends and groups in the workers’ parties of different countries. The resolutions passed by local Party organisations underscore the CPSU’s unity against Trotskyism. The addenda include - decisions adopted by the Communist International and resolutions of the Soviet trade unions against Trotskyism. The Notes facilitate the use of the material published in this book. First printing 1972 Printed in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics FOREWORD 1 LENIN’S CRITICISM OF THE OPPORTUNIST VIEWS OF THE 8 TROTSKYITES AND EXPOSURE OF THEIR SUBVERSIVE ACTIVITIES IN 1903-1917 SECOND CONGRESS OF THE RSDLP. July 17 (30)—August 10 (23), 1903 8 EXTRACTS FROM SPEECHES ON THE DISCUSSION OF THE PARTY RULES. August 2 (15). From THE LETTER TO Y. D. STASOVA, F. V. LENGNIK, AND OTHERS, October 10 14, l904 From SOCIAL-DEMOCRACY AND THE PROVISIONAL REVOLUTIONARY 11 GOVERNMENT FIFTH CONGRESS OF THE RSDLP, April 30-May 19 (May 13—June 1), 1907 13 From SPEECH ON THE REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE DUMA GROUP From THE AIM OF THE PROLETARIAN STRUGGLE IN OUR REVOLUTION TO G. -

Left Pamphlet Collection

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: Special Collection Title: Left Pamphlet Collection Scope: A collection of printed pamphlets relating to left-wing politics mainly in the 20th century Dates: 1900- Extent: over 1000 items Name of creator: University of Sheffield Library Administrative / biographical history: The collection consists of pamphlets relating to left-wing political, social and economic issues, mainly of the twentieth century. A great deal of such material exists from many sources but, as such publications are necessarily ephemeral in nature, and often produced in order to address a particular issue of the moment without any thought of their potential historical value (many are undated), they are frequently scarce, and holding them in the form of a special collection is a means of ensuring their preservation. The collection is ad hoc, and is not intended to be comprehensive. At the end of the twentieth century, which was a period of unprecedented conflict and political and economic change around the globe, it can be seen that (as with Fascism) while the more extreme totalitarian Socialist theories based on Marxist ideology have largely failed in practice, despite for many decades posing a revolutionary threat to Western liberal democracy, many of the reforms advocated by democratic Socialism have been to a degree achieved. For many decades this outcome was by no means assured, and the process by which it came about is a matter of historical significance which ephemeral publications can help to illustrate. The collection includes material issued from many different sources, both collective and individual, of widely divergent viewpoints and covering an extensive variety of topics. -

Introduction: the Rise and Decline of British Bolshevism

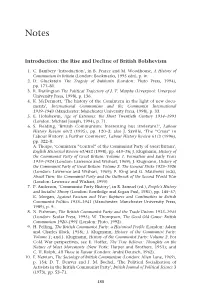

Notes Introduction: the Rise and Decline of British Bolshevism 1. C. Bambery ‘Introduction’, in B. Pearce and M. Woodhouse, A History of Communism In Britain (London: Bookmarks, 1995 edn), p. iv. 2. D. Gluckstein The Tragedy of Bukharin (London: Pluto Press, 1994), pp. 171–81. 3. R. Darlington The Political Trajectory of J. T. Murphy (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1998), p. 136. 4. K. McDermott, ‘The history of the Comintern in the light of new docu- ments’, International Communism and the Communist International 1919–1943 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p. 33. 5. E. Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: the Short Twentieth Century 1914–1991 (London: Michael Joseph, 1994), p. 71. 6. S. Fielding, ‘British Communism: Interesting but irrelevant?’, Labour History Review 60/2 (1995), pp. 120–3; also J. Saville, ‘The “Crisis” in Labour History: a Further Comment’, Labour History Review 61/3 (1996), pp. 322–8. A. Thorpe, ‘Comintern “Control” of the Communist Party of Great Britain’, English Historical Review 63/452 (1998), pp. 610–36; J. Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Volume 1. Formation and Early Years 1919–1924 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1969); J. Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Volume 2. The General Strike 1925–1926 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1969); F. King and G. Matthews (eds), About Turn: the Communist Party and the Outbreak of the Second World War (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990). 7. P. Anderson, ‘Communist Party History’, in R. Samuel (ed.), People’s History and Socialist Theory (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981), pp. 145–57; K. -

Marxism Today: an Anatomy

MARXISM TODAY: AN ANATOMY JOHN SAVILLE What do we expect from a monthly journal of the Left? Obviously it must be different, and distinguishable, from weekly journals such as Tribune and the New Statesman and Society. And with the explicit title of Marxism Today, which it must be assumed indicates a specific commitment to a marxist analysis in the elucidation of society, past, present and future, it would be reasonable to expect a serious review of the contemporary world. We would assume an historical perspective upon the world around us, one which included the kind of constant questioning of social reality to be found in the correspondence between Marx and Engels. It has always been the aim and purpose of Marxist analysis to help situate the individual within historical time; to relate the past to the present and to offer a variety of perspectives for the future; to make sense of individual purpose, a matter of self-enlightenment, within a wider social-political framework and setting. We have often been wrong, confused and blinded by a dogmatic reference to the past which has encouraged a false or one sided understanding of the present, and a mistaken prognosis of things to come. We are all, that is to say, human; but we have not always been mistaken, and readers of a journal that is titled Marxism Today expect a sharpness of intellectual approach which is serious, perceptive, and an encouragement to political action. Alongside all the criticisms we can make of ourselves, the last three decades have witnessed a significant revival of the critical spirit which moved the founding fathers. -

Brave New World

here is a good deal of talk revolution; and new forms of the these days about 'new times'. spatial organisation of social processes. This discussion is of great An issue that must perplex us is how political significance, for two total or complete this transition to Treasons. 'New times' are associated post-Fordism is. But this may be a too with the ascendancy of the Right in all-or-nothing way of posing the ques- Britain, the US and many parts of tion. In a permanently transitional age Europe. But 'new times' will also we must expect uneveness, contradic- provide the conditions - propitious or tory outcomes, disjunctures, delays, unpropitious, depending on how we contingencies, uncompleted projects, judge them - for any renewal of the overlapping emergent ones. We know Left and the project of socialism. that earlier transitions (feudalism to However, there are some real problems capitalism, household production to with this discourse of 'new times'. How modern industry) all turned out, on 'new' are they? Is it the dawn of the new inspection, to be more protracted and age or only the whimper of an old one? incomplete than the theory suggested. How do we characterise what is 'new' We have to make assessments, not about them? How do we assess their from the completed base, but from the contradictory tendencies? Are they 'leading edge' of change. The food progressive or regressive? What prom- industry, which has just arrived at the ise do they hold out for a more point where it can guarantee worldwide democratic and egalitarian future? the standardisation of the size, shape What political meaning do they have? and composition of every hamburger What are their political consequences? and every potato (sic) chip in a So far as description is concerned, Macdonald's Big Mac from Tokyo to there are several terms which have Harare, is clearly just entering its been employed to characterise these Fordist apogee. -

Stuart Hall, 1932–2014

robin blackburn STUART HALL 1932–2014 he renowned cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who died on 10 February, was the first editor ofnlr . Stepping down in 1962, he continued to play an outstanding role in the broader New Left for the rest of his life. Stuart made decisive contributions Tto cultural theory and interpretation, yet a political impulse—involving both a political challenge to dominant cultural patterns and a cultural challenge to hegemonic politics—pervades his work. His exemplary investigations came close to inventing a new field of study, ‘cultural studies’; in his vision, the new discipline was profoundly political in inspiration and radically interdisciplinary in character. Wrestling with his own identity as a West Indian-born anti-imperialist in Oxford, London and Birmingham, he evolved into his own style of Marxist. Author or co- author of a hundred texts, subject of scores of interviews, keynote speaker at many dozens of conferences, co-founder of three journals, he managed to be strikingly original and always distinctively himself. He bore nearly two decades of illness with amazing stoicism, exhibiting a tenacious hold on life and intense curiosity about the future; and helped in all this by his companion of nearly fifty years, the historian Catherine Hall. Much of Stuart’s most original and influential work widened the scope of the political by taking account of the power relations of civil society. But he did not allow an inflation of micro-politics to obscure choices and institutions at the level of society as a whole. He returned time and again to the New Left as a macro-political project, albeit one that was exploratory and pluralist—an elusive ‘floating signifier’, as he might subsequently have described it—that evolved and found new expression in every subsequent decade. -

Communists Text

The University of Manchester Research Communists and British Society 1920-1991 Document Version Proof Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K., Cohen, G., & Flinn, A. (2007). Communists and British Society 1920-1991. Rivers Oram Press. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 INTRODUCTION A dominant view of the communist party as an institution is that it provided a closed, well-ordered and intrusive political environment. The leading French scholars Claude Pennetier and Bernard Pudal discern in it a resemblance to Erving Goffman’s concept of a ‘total institution’. Brigitte Studer, another international authority, follows Sigmund Neumann in referring to it as ‘a party of absolute integration’; tran- scending national distinctions, at least in the Comintern period (1919–43) it is supposed to have comprised ‘a unitary system—which acted in an integrative fashion world-wide’.1 For those working within the so-called ‘totalitarian’ paradigm, the validity of such ‘total’ or ‘absolute’ concep- tions of communist politics has always been axiomatic.