The Homeless in a Divided Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Not-So-Spectacular Now by Gabriel Broshy

cinemann The State of the Industry Issue Cinemann Vol. IX, Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2013-2014 Letter from the Editor From the ashes a fire shall be woken, A light from the shadows shall spring; Renewed shall be blade that was broken, The crownless again shall be king. - Recited by Arwen in Peter Jackson’s adaption of the final installment ofThe Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The Return of the King, as her father prepares to reforge the shards of Narsil for Ara- gorn This year, we have a completely new board and fantastic ideas related to the worlds of cinema and television. Our focus this issue is on the states of the industries, highlighting who gets the money you pay at your local theater, the positive and negative aspects of illegal streaming, this past summer’s blockbuster flops, NBC’s recent changes to its Thursday night lineup, and many more relevant issues you may not know about as much you think you do. Of course, we also have our previews, such as American Horror Story’s third season, and our reviews, à la Break- ing Bad’s finale. So if you’re interested in the movie industry or just want to know ifGravity deserves all the fuss everyone’s been having about it, jump in! See you at the theaters, Josh Arnon Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief Senior Content Editor Design Editors Faculty Advisor Josh Arnon Danny Ehrlich Allison Chang Dr. Deborah Kassel Anne Rosenblatt Junior Content Editor Kenneth Shinozuka 2 Table of Contents Features The Conundrum that is Ben Affleck Page 4 Maddie Bender How Real is Reality TV? Page 6 Chase Kauder Launching -

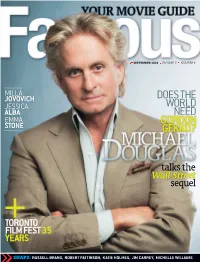

Does the World Need Gordon Gekko?

SEPTEMBER 2010 VOLUME 11 NUMBER 9 MILLA JOVOVICH DOES THE JESSICA WORLD ALBA NEED EMMA GORDON STONE GEKKO? talks the Wall Street sequel + TORONTO FILM FEST 35 YEARS PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40708019 SNAPS: RUSSELL BRAND, ROBERT PATTINSON, KATIE HOLMES, JIM CARREY, MICHELLE WILLIAMS FORDFO FLEX - With so many comfort features it’s no wonder Flex has so many fans. AAvailable features like heated leather seats, multi-panel Vista Roof™, interior refrigerator anand more. All on optional 20 inch wheels so you can ride in style, no matter where you’re ririding.d It’s a family vehicle for the whole family. Visit ford.ca for more. Starting from $29,999† MSRP Highway: 8.4L/100km (34 MPG)° City: 12.6L/100km (22 MPG)° V ehicle shown with optional equipment. °Estimated fuel consumption for 2011 Ford Flex. Fuel consumption ratings based on Transport Canada approved test methods. Actual fuel consumption may vary based on road conditions, vehicle loading and equipment, and driving habits. † 2011 Flex SE FWD starting from $29,999MSRP (Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price). Optional features, freight, Air Tax, licence, fuel fill charge, insurance, PDI, PPSA, administration fees, any environmental charges or fees, and all applicable taxes extra. Dealer may sell or lease for less. Model shown is Limited FWD starting from $41,199 MSRP. InsideFamous SEPTEMBER 2010VOLUME 11•9 regulars EDITOR’S NOTE6 CAUGHT ON FILM8 ENTERTAINMENT IN BRIEF10 SPOTLIGHT12 IN THEATRES14 STYLE42 DVD RELEASES46 TRIVIA48 FAMOUS LAST WORDS50 features DOUBLE TROUBLE20 Jessica Alba plays twins in director Robert Rodriguez’s Machete. And with four movies coming out this year, she says it not the size of the roles that counts, but how you use them • By Jim Slotek cover RUMOUR HAS IT24 story Emma Stone on playing a teen who takes control of the rumour mill in Easy A • By Bob Strauss EVIL DOER30 Milla Jovovich models, sings 34 and twitters, but nothing beats THE MONEY MAN Michael Douglasreturns as “greed is good” guru Gordon Gekko in theWall Street the rush of whacking zombies. -

Afi's 100 Years…100 Heroes and Villains Rank Heroes Villains 1

AFI'S 100 YEARS…100 HEROES AND VILLAINS RANK HEROES VILLAINS 1. Atticus Finch Dr. Hannibal Lecter (in TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD) (in THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS) 2. Indiana Jones Norman Bates (in RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK) (in PSYCHO) 3. James Bond Darth Vader (in DR. NO) (in THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK) 4. Rick Blaine The Wicked Witch of the West (in CASABLANCA) (in THE WIZARD OF OZ) 5. Will Kane Nurse Ratched (in HIGH NOON) (in ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST) 6. Clarice Starling Mr. Potter (in THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS) (in IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE) 7. Rocky Balboa Alex Forrest (in ROCKY) (in FATAL ATTRACTION) 8. Ellen Ripley Phyllis Dietrichson (in ALIENS) (in DOUBLE INDEMNITY) 9. George Bailey Regan MacNeil (in IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE) (in THE EXORCIST) 10. T. E. Lawrence The Queen (in LAWRENCE OF ARABIA) (in SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS) 11. Jefferson Smith Michael Corleone (in MR. SMITH GOES TO (in THE GODFATHER: PART II) WASHINGTON) 12. Tom Joad Alex De Large (in THE GRAPES OF WRATH) (in CLOCKWORK ORANGE) 13. Oskar Schindler HAL 9000 (in SCHINDLER’S LIST) (in 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY) 14. Han Solo The Alien (in STAR WARS) (in ALIEN) 15. Norma Rae Webster Amon Goeth (in NORMA RAE) (in SCHINDLER’S LIST) 16. Shane Noah Cross (in SHANE) (in CHINATOWN) 17. Harry Callahan Annie Wilkes (in DIRTY HARRY) (in MISERY) 18. Robin Hood The Shark (in THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN (in JAWS) HOOD) 19. Virgil Tibbs Captain Bligh (in IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT) (in MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY) 20. -

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps

WALL STREET: He’s a ‘green’ version of Gekko’s former protégé Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen) – who also makes a cameo in this MONEY NEVER SLEEPS follow-up. Jake meets his prospective father-in-law, (Cert 15) who expresses a need to be reconciled with his daughter. Reel Issues author: Clive Price Overview: Sequel to Oliver Stone’s Wall Street of Gekko shows Jake how to take revenge on merciless 1987, this latest incarnation shows fallen money guru finance executive Bretton James (Josh Brolin), who was Gordon Gekko ending his eight-year prison sentence behind the downfall of Jake’s mentor Lou Zabel (Frank for insider trading. It appears he wants to make peace Langella). However, as always, there is much more to with friends and family, but in reality he’s planning a Gekko than meets the eye. Eventually it emerges he’s return to the stock markets – with a vengeance. really after a fund belonging to his daughter. Producer and director: Oliver Stone (2010). Jake persuades Winnie to sign over her money, Length: 127 minutes. Cautions: includes swearing. thinking it could help fund an eco-friendly power scheme. But Gekko makes off with the loot. He THE FILM vanishes, leaving an empty apartment behind. Jake and Winnie split, and it looks like life is over for them. Financial wizard Gordon Gekko – played once again The turning point comes when Jake tracks him down by Michael Douglas – has paid his biggest bill yet. and shows him a video clip of his baby grandson, He’s just completed an eight-year custodial sentence growing in Winnie’s womb. -

Narcissism + Neoliberalism = the Life of I

Narcissism + Neoliberalism = The Life Of I Ross Welcome to Renegade Inc. The rise of hyper individualism and an I, me, mine, culture has encouraged two personality types to dominate business and politics. Where money, power and status lie, the corporate psychopath and the narcissist can be reliably found relentlessly chasing success at the expense of everybody else. Ross Anne Manne, welcome to Renegade Inc. Thank you very much for joining us. Anne Manne It's lovely to be with you. Ross You have thought a fair bit about two of the ills that dog Western society. One is neoliberalism and the other is narcissism. And actually, you've made a connection between the two. Just walk us through what you think that connection is. Anne Manne Perhaps if I start by just outlining the work on narcissism as to exactly what constitutes a narcissistic character. The core elements are things like having an overwhelming sense of entitlement, of being grandiose but without a commensurate kind of achievement, a willingness to exploit others and a lack of empathy - I call it the three deadly Es of narcissism - and a very unstable sense of self whereby the self esteem is too high most of the time. But if the person is criticised, they'll retaliate with humiliated fury. So this is a person also who, in the workplace, will often try and take credit for things that other people do. And they are extremely good at what they call impression management - so giving a sense of an impression of being a better person than they are, a more successful person. -

Uncorrected Transcript

1 CRISIS-2016/01/27 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION FALK AUDITORIUM IS THE NARRATIVE OF “THE BIG SHORT” THE BEST EXPLANATION OF THE FINANCIAL CRISIS? Washington, D.C. Wednesday, January 27, 2016 PARTICIPANTS: Opening Remarks: DAVID WESSEL Director, The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Senior Fellow, Economic Studies, The Brookings Institution Panel Discussion: DAVID WESSEL, Moderator Director, The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Senior Fellow, Economic Studies, The Brookings Institution ADAM McKAY Director, “The Big Short” GREG IP Chief Economics Commentator, The Wall Street Journal ADAM DAVIDSON Co-Founder and Contributor, Planet Money, NPR; Consultant for “The Big Short” Movie DONALD KOHN Senior Fellow, Economic Studies, The Brookings Institution DANNY MOSES Partner/Co-Founder, Seawolf Capital * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 CRISIS-2016/01/27 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. WESSEL: Welcome back. I’m David Wessel. I’m director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy here at Brookings. I’m pleased to be joined by Adam McKay, the director of “The Big Short.” (Applause) We have made special arrangements so everybody in this room has become a voter in the Oscars. MR. MOSES: I love it. I love it. MR. WESSEL: You may notice that the median age of this crowd is about 20 years younger than the Oscars. (Laughter) Don Kohn, who’s a colleague of mine here at Brookings. (Applause) MR. KOHN: One clapper. MR. WESSEL: Vice chairman of the Federal Reserve and is helping to keep the world safe as a member of the Financial Policy Committee of the Bank of England. -

Fictitious Capital

Fictitious Capital Fictitious Capital How Finance is Appropriating Our Future Cedric Durand Translated by David Broder VERSO London • New York For Jeanne, Loul and Isidore Thetranslation of this books was supported by the Centre national du livre (CNL). Avec.lesoutiendu Cet ouvrage publie dans le cadre du programme d'aide ala publication beneficiedu soutien du Ministere des AffairesEtrangeres et du Service Culture! de l'Ambassade de France represente aux Etats-Unis. This work received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States through their publishing assistance program. English-language edition first published by Verso 2017 Originally published in French as Le capital fictif © Les Prairies ordinaires 2014 Translation © David Broder 2017 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 13579108642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F oEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY11201 versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New LeftBooks ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-719-6 (PB) ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-284-5 (HB) ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-720-2 (UK EBK) ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-721-9 (US EBK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Durand, Caedric, author. Title: Fictitious capital : how finance is appropriating our future I Caedric Durand ; translated by David Broder. Other titles: Capital fictif. English Description: London ; Brooklyn, NY : Verso, 2017.1 "Originally published in French as Le capital fictif: Les Prairies ordinaies, 2014:' I Includes bibliographical references and index. -

8 Team Fictional Baseball Tournament Is Coming to a Computer Near You

The 1st Annual(and probably last) 8 Team Fictional Baseball Tournament is coming to a computer near you. Not to worry it's nothing dangerous. No malware, no computer viruses, no spam, and maybe no fun either. But it's free, I do most of the leg work, and there will be a prize for the victor. What more could you ask for? Besides money, power, a 68 inch plasma TV, a world full of peace, love, and puppies, or just an end to this off-topic rant. So what is it? 1. An 8 team tournament featuring 8 fictional teams, drawn from baseball movies, TV, and books, that we have all loved and cherished our whole lives. Unless you grew up in an orphanage, deep inside an abandoned Scranton coal mine, with nothing to eat but coal dust, and nothing to drink but the tears of your fellow orphans. Screams at night echoing down the dark endless coal-scarred chasms, consumed in despair and misery. Why won't somebody help me?.........sorry. 2. The 8 team names have been chosen by me. Before the tournament starts there is room for discussion on changing your team name, but the 8 I have chosen are awesome, so why would you want to change any of them. 3. The 8 stadiums have also been decided, although naming rights can be bought. (cash only) 4. Each team will have a 25 man roster. 2-c, 2-1B, 2-2B, 2-SS, 2-3B, 5-OF, 4-SP, 5-RP, 1-DH. There will be only 200 players available for drafting. -

Open Thesis-Deposit Draft.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications THE BRAND AND THE BOLD: CARTOON NETWORK’S BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD AS COMICS-LICENSED CHILDREN’S TELEVISION A Thesis in Media Studies by Zachary Roman © 2011 Zachary Roman Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2011 The thesis of Zachary Roman was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew P. McAllister Professor of Communications Thesis Advisor Barbara Bird Associate Professor of Communications Jeanne Lynn Hall Associate Professor of Communications Marie Hardin Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT This thesis critiques the animated children's television program, Batman: The Brave and the Bold, debuting in 2008 on Cartoon Network, as a synergistic corporate commodity. In the program, Batman teams up with a guest hero who helps him vanquish the villain. The commodity and commercial functions of this premise is to introduce and promote secondary licensed brands -- the “guest heroes” and “guest villains” -- for synergistic profit based on the current popularity with the program’s anchor brand, Batman. Given Time Warner's ownership of multiple media outlets including Warner Bros. Animation, DC Comics and Cartoon Network, the program serves as a bridge text to usher young consumers of Time Warner content into becoming long-term consumers of more adult iterations of many of these same characters and licenses. The thesis contextualizes the program in the larger scholarly literature of the nature of media licensing, the history of commercialism on children's television, comic books and children's media licensing. -

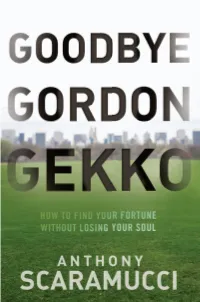

Goodbye Gordon Gekko: How to Find Your Fortune Without Losing Your

[ CONTINUED FROM FRONT FLAP ] SCARAMUCCI What does this mean in practical terms? As $27.95 USA / $33.95 CAN Scaramucci shows, it means ridding yourself of ego- PRAISE FOR tistical tendencies and developing the self-awareness to bounce back from failure. It means building a circle GOODBYE GORDON GEKKO of competence made of those you trust, mentoring e never really know how it’s going to turn and celebrating others, and giving back to your com- out. One day a community organizer, munity and country, all the while targeting success. It “A fun, easy read, with sage advice. Scaramucci is a player, looking under the the next day President. One day CEO of means seeing capitalism as an art and businesses as rocks of corruption in our fi nancial capital, and he survives as an honest soul.” Lehman Brothers, the next day the piñata for greed and ambition run amok. Life is full of decisions, creations and vocations, not simply as levers to feed- — OLIVER STONE, Three time Academy Award® Winner; ing your ego. Goodbye Gordon Gekko provides a road Director, Wall Street and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps choices, and unexpected twists and turns; how you map to help people achieve true wealth defi ned be- pick yourself up and react to these unanticipated yond a checking account. “Scaramucci’s book is a truly insightful read. It introduces us to a moral circumstances will make all the difference. compass on Wall Street—fi nding riches by direction of a true north as ANTHONY SCARAMUCCI opposed to insidious Gekko-style greed.” According to author Anthony Scaramucci, it is time to say goodbye to Gordon Gekko, the rogue character is the founder and Managing — JOSH BROLIN, Academy Award® Nominee; Actor, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps; Active Trader famously portrayed by Michael Douglas in the classic Partner of SkyBridge Capital, a movie Wall Street. -

Faith & Business

Eventide Asset Management, LLC 60 State Street, Ste. 700 Boston, MA 02109 877-771-EVEN (3836) WWW.EVENTIDEFUNDS.COM DECEMBER 21, 2014 A Tale of Two Capitalisms It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way . These are among the most famous opening lines in all of literature, probably rivaled only by “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” They are, of course, the first lines from A Tale of Two Cities by the great nineteenth FAITH & BUSINESS century English novelist, Charles Dickens. Interestingly, they could serve equally TIM WEINHOLD well as the introduction to another popular work of fiction — It’s A Wonderful Life by Frank Capra . a mid-twentieth-century film that is now almost as much a part of our American Christmas holidays as Santa Claus himself. Tim Weinhold serves as Director of Eventide's Faith The two cities to which Dickens’ title alludes are London and Paris. More than & Business Initiative, and has served in a faith and Alexandre or Lucie Manette, more than Charles Darnay or Sydney Carton, it is business/investing thought leadership capacity these two cities that serve as the story’s principal protagonists. -

Beyond Greed Is Good: Pop Culture in the Business Law Classroom

23 Beyond Greed is Good: Pop Culture in the Business Law Classroom Felice Batlan and Joshua Bass Popular culture often projects a narrow view of what lawyers do and of what lawyering entails. Many movies, television shows, cartoons, and novels portray lawyers primarily as litigators, with the climax of the story consisting of an epic courtroom battle.1 The very architecture of law schools, with their lavish moot court and trial advocacy courtrooms, quietly enshrines a normative vision of what the practice of law means.2 Of course, the readings that comprise most of a casebook are appellate decisions that feed the conception that the lawyers’ natural place is in the courtroom and that law is produced by appellate courts. Given these messages, it is no wonder that some students take business organizations classes, believing the subject is tangential to some of the “big” issues discussed in classes such constitutional or criminal law. Many students fear that they have little or no background in business, or that there will be too many “numbers.” For some, the very concept of a business organization is abstract, opaque, and passionless.3 This article explores how popular culture can be used in business organizations courses to expand students’ horizons, while also raising crucial Felice Batlan is Professor of Law, IIT/Chicago-Kent College of Law; Joshua Bass, IIT/Chicago- Kent College of Law. Note from Felice Batlan: As this essay is about using popular culture in the classroom, it seemed essential to co-author it with a student. Mr. Bass was a student in my business organizations class in spring 2017.