Active Transportation and Transit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Sauvie Island Quadrangle, Multnomah and Columbia Counties, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington

Geologic Map of the Sauvie Island Quadrangle, Multnomah and Columbia Counties, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington By Russell C. Evarts, Jim E. O'Connor, and Charles M. Cannon Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3349 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Suggested citation: Evarts, R.C., O'Connor, J.E., and Cannon, C.M., 2016, Geologic map of the Sauvie Island quadrangle, Multnomah and Columbia Counties, Oregon, and Clark County, Washington: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3349, scale 1:24,000, pamphlet 34 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/sim3349. ISSN 2329-132X (online) Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Marriage of Basalt and His Wife River by Rick Rubin ©2001

The Marriage of Basalt and his Wife River By Rick Rubin ©2001 Sixteen million years ago, a vast outpouring of lava from eastern Oregon began. The greatest lava flow in North America, that lava covered 80,000 square miles with molten rock. At that time, the Columbia River had her bed where Salem is now. A (miocene) basalt path, covered by (Quaternary) alluvial sediment just south of Salem shows the place. Her bed reached the sea north of the present Lincoln City. That lava outpouring got into her bed. Filled it up. Got hard. Became grass covered Cascade Head, north of Lincoln City. Husband-like, Basalt shouldered his river/wife north and west. She had to make a new bed for herself. Time and again those cracks to the east poured out lava, which flowed down the river’s new bed, which was always to the north of the earlier one, and came to the sea, or perhaps simply stopped, for the sea was as much as 300 miles farther west than it is now some of the time. (That was Ice Age’s doing. The Earth’s water was all tied up in glacier ice). The next time fiery Basalt poured out from east of where the Cascade mountains are now, and coming into Columbia River’s bed flowed down to the sea, it cooled into slim, steep sided, jutting Cape Lookout A million or so years later, Basalt flowed into the river’s attractive bed again, and this time, when he reached the sea, became blocky Cape Meares, just south of Tillamook Bay Later Basalt may have made a cape at the north entrance to Great Basin petroglyphs from Petroglyphs of Oregon, Luther Cressmann, Tillamook Bay of which some basalt rocks near the shore are the only relics. -

Tualatin Valley Scenic Bikeway Management Plan Washington County, Oregon March 1, 2013

Tualatin Valley Scenic Bikeway Management Plan Washington County, Oregon March 1, 2013 Revised March 20, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 Proponent contact information 2 Route map 3-4 Sign plan introduction 5 Sign location table 6-9 Field-checked turn-by-turn cue sheet 10-11 Final letters of support from all road jurisdictions 12-25 Records of public notification 26 Map features 27-28 State Congressional representatives 28 Overarching objectives 29 Business target markets 29-30 Cyclist categories 31 Web action items / Ongoing Web communications 31-32 General marketing action items 32 Ride description 33 Talking points 33-34 Measurable objectives 34 Electronic photos 34 Preservation and enhancement goals 35-37 Tualatin Valley Scenic Bikeway Management Plan 1 | Page Proponent Contact Information Contact Name, Agency Contact Info Role Carolyn McCormick 11000 SW Stratus St., Ste. 170 Coordinates marketing and President/CEO, Washington Beaverton, OR 97008 promotion, steering County Visitors Association Phone: 503-644-5555 committee, signage, Email: [email protected] jurisdiction involvement Allison George 11000 SW Stratus St., Ste. 170 Coordinates outreach and Stakeholder Development Beaverton, OR 97008 engagement of local Manager, Washington County Phone: 503-644-5555 tourism-related businesses Visitors Association Email: [email protected] along the route Joy Lalic Chang 155 N. First Ave., Ste. 350-14 Traffic engineering and Associate Planner Hillsboro, OR 97124 coordination with Washington County Long Phone: 503-846-3873 maintenance/operations on Range Planning Email: [email protected] Washington County roads Jolynn Becker 13680 NW Main St. Interim City Manager Banks, OR 97106 Point of contact for Banks City of Banks Phone: 503-324-5112 ext. -

WASH CTY NOV 2002.Qxd

Washington Elections Division 3700 SW Murray Blvd. Beaverton, OR 97005 County voters’ pamphlet VOTE-BY-MAIL ELECTION NOVEMBER 5, 2002 To be counted, voted ballots must be in our office Washington County by 8:00 pm on Board of County Commissioners NOVEMBER 5, 2002 Tom Brian, Chair Dick Schouten, District 1 John Leeper, District 2 Roy Rogers, District 3 Andy Duyck, District 4 Attention: This is the beginning of your county voters’ Dear Voter: pamphlet. The county portion of this joint vot- This pamphlet contains information for several districts and there may be ers’ pamphlet is inserted in the center of the candidates/measures included that are not on your ballot. If you have state portion. Each page of the county voters’ any questions, call 503-846-5800. pamphlet is clearly marked with a color bar on the outside edge. All information contained in Attention: the county portion of this pamphlet has been Washington County Elections prints information as submitted. We do not assembled and printed by your County correct spelling, punctuation, Elections Official. grammar, syntax, errors or inaccurate information. W-2 W-3 WASHINGTON COUNTY Commissioner At Large TOM BRIAN (NONPARTISAN) OCCUPATION: Chairman, Washington County Board of Commissioners, 1999 to present. OCCUPATIONAL BACKGROUND: Business consultant; State Representative 1989-1999; Small business owner, 18 years; Director, Oregon Council on Crime and Delinquency, 6 years; Deputy Sheriff, 3 years. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Bachelor of Science, Western Oregon University; Masters in Public Administration program (1976-78), Portland State University; Executive Program, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 2001. PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL EXPERIENCE: State Representative, 1989-1999. -

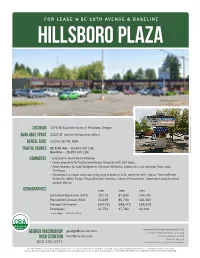

George Macoubray Nick Stanton

FOR LEASE » SE 10TH AVENUE & BASELINE HILLSBORO PLAZA Location 1075 SE Baseline Street in Hillsboro, Oregon Available Space 2,820 SF (former chiropractic office) Rental Rate $17.00/SF/YR, NNN Traffic CountS SE 10th Ave – 84,493 ADT (18) Baseline – 28,194 ADT (18) Comments • Located in downtown Hillsboro. • Close proximity to Tuality Healthcare Hospital with 167 beds. • Area retailers include Walgreens, Sherwin Williams, Starbucks, Les Schwab Tires, and Thriftway. • Hillsboro is a major manufacturing and economic hub, home to Intel, Qorvo, ThermoFisher Scientific, Wells Fargo, Tokyo Electron America, Kaiser Permanente, Genentech and Acumed, among others. Demographics 1 MILE 3 MILE 5 MILE Estimated Population 2019 23,113 81,909 154,197 Population Forecast 2024 24,229 85,706 161,342 Average HH Income $64,715 $98,472 $95,309 Employees 11,752 37,782 62,316 Source: Regis – SitesUSA (2019) CRA Commercial Realty Advisors NW LLC george macoubray [email protected] 733 SW Second Avenue, Suite 200 nick stanton [email protected] Portland, Oregon 97204 www.cra-nw.com 503.274.0211 Licensed brokers in Oregon & Washington The information herein has been obtained from sources we deem reliable. We do not, however, guarantee its accuracy. All information should be verified prior to purchase/leasing. View the Real Estate Agency Pamphlet by visiting our website, www.cra-nw.com/real-estate-agency-pamphlet/. CRA PRINTS WITH 30% POST-CONSUMER, RECYCLED-CONTENT MATERIAL 7,600 Seats HILLSBORO, OREGON 1,000 Employees NE Evergreen Pkwy NE Evergreen Pkwy JONES FARM 6,019 Employees FEI TANASBOURNE RONLER ACRES TOWN CENTER 7,043 Employees STREETS OF NE Cornell Road 1000 Employees TANASBOURNE Hillsboro Airport ORENCO STATION TOWN CENTER NE Cornell Road HAWTHORN FARM 1,612 Employees MAX LIGHT RAIL MAX LIGHT RAIL 1,275 Employees SITE TUALITY HOSPITAL 167 BEDS SUNSET ESPLANADE SHOPPING CENTER ALOHA CAMPUS n CRA HILLSBORO, OREGON│DOWNTOWN LINCOLN STREET ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SYAN IZAKAYA WASHINGTON CO. -

The Petrology and Stratigraphy of the Portland Hills Silt Portland Hills Silt, Which Once Covered Much of This Area

OREGON GEOLOGY published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries VOLUME 43 , NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1981 DOGAMI laboratory policy revised OREGON GEOLOGY (ISSN 0164-3304) The greatly increased need for systematic rock-chemistry data for Oregon has prompted the Oregon Department of VOLUME 43, NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1981 Geology and Mineral Industries to enlarge the scope of its laboratory facilities. The Department lab is managed by Published monthly by the State of Oregon Department of Assayer-Spectroscopist Gary Baxter. Geology and Mineral Industries (Volumes 1 through 40 were en Effective January 1, 1981, the Department's revised pur titled The Ore Bin). poses and procedures include the following: The laboratory will be primarily research oriented, with the view of providing necessary support for staff geologists in Governing Board a manner analogous to the library, cartographic, and editorial John L. Schwabe, Chairman ................... Portland C. Stanley Rasmussen ........ .. Baker sections of the Department. Allen P. Stinchfield ........................ North Bend The laboratory is continuing its service to the public on routine assays and analyses, but it can no longer perform the State Geologist . .. Donald A. Hull analyses in-house. Instead, gold and silver assays and heavy metal and other analyses are now being farmed 'Out to com Deputy State Geologist ..................... John D. Beaulieu merciallabs on an annual-bid basis. The Department performs random quality-control checks and crushing and grinding. A Editor ................................... BeverlyF. Vogt new price list, schedule, and other procedural instructions will be published at a later date. Main Office: 1005 State Office Building, Portland 97201, phone (503) 229-5580. Departmental lab capabilities continue to be ,oriented toward fire assay, geochemical analysis of metals, future im Baker Field Office: 2033 First Street, Baker 97814, phone (503) provement of geochemical capabilities for soil and rock, and 523-3133. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

Geologic Formations of Western Oregon

BULLETIN 70 GEOLOGIC fORMATION§ OF WESTERN OREGON WEST OF LONGITUDE 121° 30' STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1971 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1069 Stal·e Office Building Portland, Oregon 97201 BULLETIN 70 GEOLOGIC FORMATIONS OF WESTERN OREGON (WEST OF LONGITUDE 12 1 °30') By John D. Beaulieu 1971 GOVERNING BOARD Fayette I. Bristol, Rogue River, Chairman R. W. deWeese, Portland Harold Banta, Baker STATE GEOLOGIST R. E. Corcoran CONTENTS Introduction . Acknowledgements 2 Geologic formations 3 Quadrang I es. 53 Corre I ation charts. 60 Bibliography. 63 ii GE OLOGIC FORMA T IONS OF WESTERN OR EGON (W E ST OF LONG ITUD E 12 1°30') By John D. Beaulieu* INTRODUCTION It is the purpose of th is publi cation to provide a concise , yet comprehensive discussion of the for mations of western Oregon. It is the further aim that the data for each of the formations be as current as possi ble. Consequently, the emphasis has been placed on th e recent literature . Although this paper should not be viewed as a discussion of the historical development of each of the fo rmations, the original reference for each of the units is given . Also, in cases where the historical development of the formation has a direct bearing on present-day problems it is included in the discussion . A wide variety of published literature and unpublished reports , theses, and dissertations was con sul ted and several professional opin ions regarding specific problems were so licited . In recent years re search has been concentrated in the Klamath Mountains and the southern Coast Range and for these regions literature was volumi nous. -

Orenco Station Town Center for Lease | Hillsboro, Oregon

ORENCO STATION TOWN CENTER FOR LEASE | HILLSBORO, OREGON Location Cornell Rd & Orenco Station Pkwy in Hillsboro, OR Available Space 1,540 SF Rental Rate $30.00/SF/YR, NNN Comments Beautiful retail shop space available at Portland’s award-winning suburban mixed-use development. Anchored by New Seasons, Orenco Station Town Center is surrounded by vibrant neighborhoods, major employers such as Intel, and other high-volume retailers such as Costco, WinCo, Kohls & Walgreens. Traffic CountS Cornell Rd – 29,388 ADT (17) Demographics 1 MILE 3 MILE 5 MILE Estimated Population 2018 14,288 120,718 243,964 Population Forecast 2023 14,980 126,440 255,680 Average HH Income $106,284 $96,334 $100,403 Employees 15,376 47,383 91,642 Source: Regis – SitesUSA (2018) CRA Commercial Realty Advisors NW LLC JEFF OLSON 733 SW Second Avenue, Suite 200 503.274.0211 Portland, Oregon 97204 www.cra-nw.com [email protected] Licensed brokers in Oregon & Washington The information herein has been obtained from sources we deem reliable. We do not, however, guarantee its accuracy. All information should be verified prior to purchase/leasing. View the Real Estate Agency Pamphlet by visiting our website, www.cra-nw.com/real-estate-agency-pamphlet/. CRA PRINTS WITH 30% POST-CONSUMER, RECYCLED-CONTENT MATERIAL 7,600 Seats HILLSBORO, OREGON 1,000 Employees NE Evergreen Pkwy NE Evergreen Pkwy JONES FARM 6,019 Employees FEI TANASBOURNE RONLER ACRES TOWN CENTER 7,043 Employees STREETS OF NE Cornell Road 1000 Employees TANASBOURNE Hillsboro Airport ORENCO STATION TOWN CENTER SITE -

Bono De HSD Página 3

UNA MIRADA AL INTERIOR Octubre 2017 El conocido orador nacional Keith Deltano dirige asambleas de unidad, página 13 Bono de HSD página 3 El distrito propone un bono de capital para proyectos construcción de $408 millones en las próximas elecciones el 7 de noviembre; el bono no aumentaría el índice contributivo actual. mensaje del Caminos a la profesiÓn Voluntarios superintendente y a la universidad y Donaciones Escuelas sólidas = comunidad sólida Crédito dual, expansión de programas CTE HSD tiene un apoyo sólido página 2 página 13 página 14 Informes de los grupos de escuelas: Century 4 | Glencoe 5 | Hilhi 6 | Liberty 7 Hillsboro Online Academy 10 | Miller Education Center 10 Calendarios 8-9 Voluntarios 14 Socios de la comunidad 15 3083 NE 49th Place l Hillsboro, OR 97124 503.844.1500 l www.hsd.k12.or.us 2 │ UNA MIRADA AL INTERIOR Hillsboro School District Octubre 2017 escuelas soólidas = comunidad soólida Compromiso con la comunidad, esto simplemente no es el caso. No hay ningún cultura y profesión las áreas del Distrito para asegurar que conti otro mecanismo de financiación en Oregón para Aunque hay mucho trabajo por hacer en todas la construcción de escuelas u otras inversiones de nuestros estudiantes, creemos que podemos grandes de capital que los bonos de obligación tenernuamente un impactomaximizamos mensurable la experiencia en nuestro educa tiva ob tenciageneral del que distrito se so meten escolar. a votación y se aprueban por los propietarios que viven en la zona de asis Hemos escuchado, “Pero, ¿seguramente no cons jetivo estratégico de todos los estu diantes que truirían a South Hillsboro sin tener escuelas seacuerdos gradúan y compromisos preparados conde nuestrodestrezas Plan para estra la allí?”, y hemos tenido que decir que eso es exac pro fesión y la universidad, enfocándonos en los tamente lo que sucedería hasta y a menos que los Mensaje del superintendente tégico 2016-2021 de conectar a los estu diantes Paracon la el comunidad, plan de trabajo cultura de yeste profesión. -

Parks & Recreation Commission

PARKS & RECREATION COMMISSION TELECONFERENCE MEETING AGENDA Tuesday, June 9, 2020 Sign-language interpreters are available at no cost. Please call 503-681-6100 or TTY 503-681-6284, 72 hours prior to the meeting. Parks & Recreation Commission - 9 am - Teleconference The City of Hillsboro invites you to listen to the Tuesday, June 9 teleconference Parks and Recreation Commission meeting using the Zoom meeting details below. Zoom Teleconference Phone: +1 669 900 6833 or +1 253 215 8782 Meeting ID: 841 5347 0520 Please click the link below to join the webinar: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84153470520 Call to Order - Roll Call 1. Public Comment Public Comment will not be received during this meeting but can be emailed to [email protected] before 8 am Monday, June 8. 2. Consider Minutes 2.1. Parks & Recreation Commission Minutes May 26, 2020. Parks & Recreation Commission Meeting Minutes - May 26, 2020 3. Reports/Presentations 3.1. Community Senior Center - Thompson & Stark 4. Director/Manager Updates 4.1. Miletich - Parks & Recreation 4.2. Nye - Pride Party 4.3. Pipher - Dairy Creek Park 4.4. Kok - Projects 4.5. Morgan - Recreation 5. New Business 5.1. Consider adopting the Fiscal Year 2020-2021 Parks & Recreation Department Capital Improvement Plan (CIP). Staff Report Draft Parks CIP 2020-21 Final 6. Old Business None. 7. Advice/Information Items 7.1. Hillsboro's Public Art Collection is Online! Hillsboro Public Art Archive Page 2 of 10 Hillsboro Parks and Recreation Commission Minutes Regular Session May 26, 2020 9:00 a.m. Zoom Teleconference The Hillsboro Parks and Recreation Commission met in regular session. -

WASHINGTON STREET STATION 20 Units • Hillsboro, Oregon OFFERING MEMORANDUM

WASHINGTON STREET STATION 20 Units • Hillsboro, Oregon OFFERING MEMORANDUM www.hfore.com (503) 241.5541 2 HFO INVESTMENT REAL ESTATE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ASSET SUMMARY DETAILED UNIT MIX Location 433 SE Washington Street Unit Type Unit Count Average Sq Ft Total Sq Ft % of Total Units City, State Hillsboro, OR 97123 1 Bed / 1 Bath 2 548 1,096 10.0% County Washington 1 Bed / 1 Bath 8 600 4,800 40.0% 2 Bed/ 2 Bath Total Units 20 6 1,243 7,458 30.0% Townhome Year Built 2012 2 Bed / 2 Bath 4 1,330 5,320 20.0% Approx. NR Sq Ft 18,674 Total / Averages 20 934 18,674 100.0% Average Unit Size 934 Washington Street Station is a 20-unit community in the heart of downtown PRICE SUMMARY Hillsboro. The property offers tenants spacious one-bed, one-bath and large two- bed, two-bath layouts. Apartments average 934 square feet and have modern Price $4,400,000 fixtures and amenities throughout. Price Per Unit $220,000 Washington Street Station is situated on SE Washington Street between SE 4th and Per Square Foot $236 5th Streets just one block from the Hillsboro Central MAX station. Its accessible Projected Cap Rate 5.91% location offers numerous amenities within walking distance including Walgreens, Starbucks, Insomnia Coffee, Shute Park, Tuality Community Hospital, and an abundance of restaurants and retailers. Washington Street Station’s rents currently TOURS AND INQUIRIES average $1,409 per unit or $1.51 per square foot; projected rents average $1,480 per unit or $1.58 per sq ft.