Lyellcollection.Org/ at University of Arizona on June 24, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vita Scientia Revista De Ciências Biológicas Do CCBS

Volume III - Encarte especial - 2020 Vita Scientia Revista de Ciências Biológicas do CCBS © 2020 Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie Os direitos de publicação desta revista são da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Os textos publicados na revista são de inteira responsabilidade de seus autores. Permite-se a reprodução desde que citada a fonte. A revista Vita Scientia está disponível em: http://vitascientiaweb.wordpress.com Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Vita Scientia: Revista Mackenzista de Ciências Biológi- cas/Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Semestral ISSN:2595-7325 UNIVERSIDADE PRESBITERIANA MACKENZIE Reitor: Marco Túllio de Castro Vasconcelos Chanceler: Robinson Granjeiro Pro-Reitoria de Graduação: Janette Brunstein Pro-Reitoria de Extensão e Cultura: Marcelo Martins Bueno Pro-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação: Felipe Chiarello de Souza Pinto Diretora do Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde: Berenice Carpigiani Coordenador do Curso de Ciências Biológicas: Adriano Monteiro de Castro Endereço para correspondência Revista Vita Scientia Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie Rua da Consolação 930, São Paulo (SP) CEP 01302907 E-mail: [email protected] Revista Vita Scientia CONSELHO EDITORIAL Adriano Monteiro de Castro Camila Sachelli Ramos Fabiano Fonseca da Silva Leandro Tavares Azevedo Vieira Patrícia Fiorino Roberta Monterazzo Cysneiros Vera de Moura Azevedo Farah Carlos Eduardo Martins EDITORES Magno Botelho Castelo Branco Waldir Stefano CAPA Bruna Araujo PERIDIOCIDADE Publicação semestral IDIOMAS Artigos publicados em português ou inglês Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, Revista Vita Scientia Rua da Consolaçãoo 930, Edíficio João Calvino, Mezanino Higienópolis, São Paulo (SP) CEP 01302-907 (11)2766-7364 Apresentação A revista Vita Scientia publica semestralmente textos das diferentes áreas da Biologia, escritos em por- tuguês ou inglês: Artigo resultados científicos originais. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Newsletter Number 77

The Palaeontology Newsletter Contents 77 Association Business 2 Association Meetings 18 News 23 Advert: National Fossil Day 27 From our correspondents Invasion of the Dinosaur 28 PalaeoMath 101: Complex outlines 36 Future meetings of other bodies 46 Meeting Report Progressive Palaeontology 2011 54 Mystery Fossil 21: update 58 Obituary Frank K. McKinney 60 Reporter: a fossiliferous Countdown 62 Graduate opportunities in palaeontology 67 Book Reviews 68 Special Papers 85: Asteroidea 83 Palaeontology vol 54 parts 3 & 4 84–85 Discounts for PalAss members 86 Reminder: The deadline for copy for Issue no 78 is 3rd November 2011. On the Web: <http://www.palass.org/> ISSN: 0954-9900 Newsletter 77 2 Association Business Annual Meeting 2011 Notification is given of the 54th Annual General Meeting and Annual Address This will be held at the University of Plymouth on 18th December 2011, following the scientific sessions. AGENDA 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of the 53rd AGM, University of Ghent 3. Trustees Annual Report for 2010 4. Accounts and Balance Sheet for 2010 5. Election of Council and vote of thanks to retiring members 6. Report on Council Awards 7. Annual address DRAFT AGM MINUTES 2010 Minutes of the Annual General Meeting held on Saturday, 18th December 2010 at the University of Ghent. 1 Apologies for absence: Prof. J. C. W. Cope 2 Minutes: Agreed a correct record 3 Trustees Annual Report for 2009. Proposed by Dr L. R. M. Cocks and seconded by Prof. G. D. Sevastopoulo, the report was agreed by unanimous vote of the meeting. 4 Accounts and Balance Sheet for 2009 . -

Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature

\M RD IV WV The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature IGzjJxjThe Official Periodical of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature Volume 56, 1999 Published on behalf of the Commission by The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature c/o The Natural History Museum Cromwell Road London, SW7 5BD, U.K. ISSN 0007-5167 '£' International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 56(4) December 1999 I TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Notices 1 The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and its publications . 2 Addresses of members of the Commission 3 International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 4 The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature 5 Towards Stability in the Names of Animals 5 General Article Recording and registration of new scientific names: a simulation of the mechanism proposed (but not adopted) for the International Code of Zoological Nomen- clature. P. Bouchet 6 Applications Eiulendriwn arbuscula Wright, 1859 (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa): proposed conservation of the specific name. A.C. Marques & W. Vervoort 16 AUGOCHLORiNi Moure. 1943 (Insecta. Hymenoptera): proposed precedence over oxYSTOGLOSSiNi Schrottky, 1909. M.S. Engel 19 Strongylogasier Dahlbom. 1835 (Insecta. Hymenoptera): proposed conservation by the designation of Teiuhredo muhifascuim Geoffroy in Fourcroy, 1785 as the type species. S.M. Blank, A. Taeger & T. Naito 23 Solowpsis inviclu Buren, 1972 (Insecta, Hymenoptera): proposed conservation of the specific name. S.O. Shattuck. S.D. Porter & D.P. Wojcik 27 NYMPHLILINAE Duponchel, [1845] (Insecta, Lepidoptera): proposed precedence over ACENTROPiNAE Stephens. 1835. M.A. Solis 31 Hemibagnis Bleeker, 1862 (Osteichthyes, Siluriformes): proposed stability of nomenclature by the designation of a single neotype for both Bagrus neimirus Valenciennes, 1840 and B. -

Designing the Dinosaur: Richard Owen's Response to Robert Edmond Grant Author(S): Adrian J

Designing the Dinosaur: Richard Owen's Response to Robert Edmond Grant Author(s): Adrian J. Desmond Source: Isis, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Jun., 1979), pp. 224-234 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/230789 . Accessed: 16/10/2013 13:00 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 150.135.115.18 on Wed, 16 Oct 2013 13:00:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Designing the Dinosaur: Richard Owen's Response to Robert Edmond Grant By Adrian J. Desmond* I N THEIR PAPER on "The Earliest Discoveries of Dinosaurs" Justin Delair and William Sarjeant permit Richard Owen to step in at the last moment and cap two decades of frenzied fossil collecting with the word "dinosaur."' This approach, I believe, denies Owen's real achievement while leaving a less than fair impression of the creative aspect of science. -

Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness

The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon Volume 84 Issue 1 Article 8 1-6-2012 Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/compass Part of the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2012) "Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness," The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon: Vol. 84: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/compass/vol84/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Figure. 1. Portrait of Mary Anning, in oils, probably painted by William Gray in February, 1842, for exhibition at the Royal Academy, but rejected. The portrait includes the fossil cliffs of Lyme Bay in the background. Mary is pointing at an ammonite, with her companion Tray dutifully curled beside the ammonite protecting the find. The portrait eventually became the property of Joseph, Mary‟s brother, and in 1935, was presented to the Geology Department, British Museum, by Mary‟s great-great niece Annette Anning (1876-1938). The portrait is now in the Earth Sciences Library, British Museum of Natural History. A similar portrait in pastels by B.J.M. Donne, hangs in the entry hall of the Geological Society of London. -

A Four-Legged Megalosaurus and Swimming Brontosaurs

Channels: Where Disciplines Meet Volume 2 Number 2 Spring 2018 Article 5 April 2018 A Four-Legged Megalosaurus and Swimming Brontosaurs Jordan C. Oldham Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/channels Part of the Geology Commons, History of Philosophy Commons, Paleontology Commons, and the Philosophy of Science Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Oldham, Jordan C. (2018) "A Four-Legged Megalosaurus and Swimming Brontosaurs," Channels: Where Disciplines Meet: Vol. 2 : No. 2 , Article 5. DOI: 10.15385/jch.2018.2.2.5 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/channels/vol2/iss2/5 A Four-Legged Megalosaurus and Swimming Brontosaurs Abstract Thomas Kuhn in his famous work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions laid out the framework for his theory of how science changes. At the advent of dinosaur paleontology fossil hunters like Gideon Mantell discovered some of the first dinosaurs like Iguanodon and Megalosaurus. Through new disciples like Georges Cuvier’s comparative anatomy lead early dinosaur paleontologist to reconstruct them like giant reptiles of absurd proportions. This lead to the formation of a new paradigm that prehistoric animals like dinosaurs existed and eventually went extinct. -

Gideon Mantell 3Rd Feb 1790 — 10 Th November 1852

Gideon Mantell 3rd Feb 1790 — 10 th November 1852 In 1990, on the 200 th anniversary of his birth, Lewes celebrated the memory and achievements of one of its most gifted sons: Gideon Mantell, a working doctor and surgeon with a passionate interest in fossils and the geology of southern England. The occasion was marked by exhibitions, public lectures and a symposium at Sussex University, at which Dennis R. Dean presented and previewed the findings of the detailed research for his seminal book ‘Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of the Dinosaurs’, published nine years later. ‘I soon came to see’, he writes, ‘that the early history of dinosaur discoveries was rather different than had been previously supposed.’ Deborah Cadbury’s ‘The Dinosaur Hunters’ (2000), a less academic and more popular scientific account, reinforced this new narrative, in which Gideon Mantell plays a much more central and important role than had previously been recognised. Virtually every popular book on dinosaurs, past and present, mentions Mantell only in connection with his – or his wife’s - discovery of an unusual fossil tooth that led him to identify a previ - ously unknown creature, later identified as an Iguanodon. By contrast, Professor Dean first argues that the geological and paleontological history of life and landforms in southeast England ‘was entirely unsuspected when Gideon Mantell was born in 1790 and known only imperfectly when he died in 1852; a surprising amount of the intervening progress...is attributable to him’. ‘It is not commonly appreciated that he devoted some thirty years to his increasingly accurate reconstructions of Iguanodon, while discovering seven other dinosaurs as well’. -

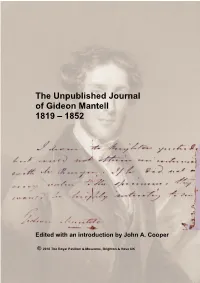

The Unpublished Journal of Gideon Mantell 1819 – 1852

The Unpublished Journal of Gideon Mantell 1819 – 1852 Edited with an introduction by John A. Cooper © 2010 The Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove UK 1 The Unpublished Journal of Gideon Mantell: 1819 – 1852 Introduction Historians of English society of the early 19th century, particularly those interested in the history of science, will be familiar with the journal of Gideon Algernon Mantell (1790-1852). Whilst not kept on a daily basis, Mantell’s journal, kept from 1818, offers valuable insights into not only his own remarkable life and work, but through his comments on a huge range of issues and personalities, contributes much to our understanding of contemporary science and society. Gideon Mantell died in 1852. All of his extensive archives passed first to his son Reginald and on his death, to his younger son Walter who in 1840 had emigrated to New Zealand. These papers together with Walter’s own library and papers were donated to the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, New Zealand in 1927 by his daughter-in- law. At some time after that, a typescript was produced of the entire 4-volume manuscript journal and it is this typescript which has been the principal reference point for subsequent workers. In particular, an original copy was lodged with the Sussex Archaeological Society in Lewes, Sussex. In 1940, E. Cecil Curwen published his abridged version of Gideon Mantell’s Journal (Oxford University Press 1940) and his pencilled marks on the typescript indicate those portions of the text which he reproduced. About half of the text was published by Curwen. -

Gideon Algernon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Born Gideon Algernon Mantell in Lewes, East Sussex, on 3rd February, the son 1790 of a shoemaker 1805 Apprenticed to James Moore, surgeon in Lewes 1811 Gained diploma for MRCS 1813 Published in Sussex Advertiser ‘Geology of the Environs of Lewes’ 1814 First published geological paper Married Mary Ann Woodhouse. Appointed military surgeon at the Royal 1816 Artillery Hospital, Ringmer, Lewes. Purchased practice of James Moore at Lewes for £95 Purchased 2 houses at Castle Place, Lewes. Published A Sketch of the 1818 Geological Structure of the South-eastern part of Sussex. Birth of his first child, Ellen Maria, on 30th May 1820 Birth of his second child, Walter, March 11th Published The Fossils of the South Downs. Discovery of Iguanodon tooth by 1822 Mary Ann. Birth of third child, Hannah, on November 24th 1825 Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 28th October Published Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex: The Fossils of Tilgate Forest. Published Observations on the Medical Evidence necessary to prove 1827 the presence of Arsenic in the Human body. Birth of his fourth child, Reginald, August 11th 1831 Published The Age of Reptiles Published The Geology of South-East England. Moved to 20, The 1833 Steyne,Brighton. Opened his house as a Fossil Museum - the first in Britain. 1834 Discovery of the Maidstone Iguanodon 1836 Published Thoughts on a Pebble, dedicated to his youngest son Richard 1837 His daughter Hannah falls ill in April Very ill - ‘much broken in health and spirits’. Wrote to Natural History 1838 Museum, offering his entire collection for £5000. -

Outside Medicine Gideon Algernon Mantell

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 1 MARCH 1975 505 Outside Medicine Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.1.5956.505 on 1 March 1975. Downloaded from Gideon Algernon Mantell W. E. SWINTON British Medical Journal, 1975, 1, 505-507 see as many as he could. He appears at this time to have been indefatigable and ambitious. One can visualize him in the little hilly town (of which he was to write a guide in 1846) striding Gideon Mantell was primarily a doctor, practising his profession along, acknowledging his many acquaintances, yet keeping an all his adult life. He was known to most of the leading scientists eye on the distant prospects, some of which he would investigate and medical men, and he was attended by distinguished col- archaeologically with more enthusiasm than skill. leagues during the painful last 11 years of his life. He was studious, industrious, and only moderately successful in his profession; he was unhappy in his private life; but his scientific studies earned him fame. None of this explains why he is mentioned in most encyclo- paedias, and has more than a page in the D.N.B. His diary was edited and annotated by a doctor, Dr. E. Cecil Curwen', and is sometimes to be had today. His biography, by another doctor Dr. Sidney Spokes,2 is almost impossible to obtain new or secondhand. His most enthusiastic supporters today are Sussex doctors, Dr. Jack Palmer of South Chailey and Dr. A. D. Morris of Eastbourne.3 Early Life http://www.bmj.com/ He was born on 3 February 1790, a son of a Lewes shoemaker, who was relatively prosperous and of strict principles, so young Gideon was educated at a Dame's School in Lewes and later, under the tutelage of his parson uncle, at Swindon. -

Progressionism in the 1850S: Lyell, Owen, Mantell and the Elgin Fossil Reptile <Italic>Leptopleuron (Telerpeton)</Itali

Archives ofNatural History (1982) 11 (1): 123-136 Progressionism in the 1850s: Lyell, Owen, Mantell and the Elgin fossil reptile Leptopleuron (Telerpeton) By MICHAEL J. BENTON University Museum, Parks Raod, Oxford 0X1 3PW. SUMMARY The advanced fossil reptile Leptopleuron (Telerpeton), collected in 1851 from supposedly Old Red Sandstone rocks near Elgin, northern Scotland, was regarded by Charles Lyell as good evidence for his anti-progressionist views. The specimen was sent to London to be described by Richard Owen, who published a brief account of it. Gideon Mantell then published a longer description of the same specimen, apparently at the request of its discoverer. The general opinion, then and now, has been that Owen acted badly, as he apparently did in other cases, because of his personal enmity towards both Lyell and Mantell. However, new evidence from previously unpublished archive materials shows that Lyell urged the ailing Mantell to produce a description at speed, in full knowledge that Owen was also doing so. Leptopleuron was almost the last piece of evidence that Lyell proposed as evidence against progressionism, and he was happy to accept its true Triassic age by I860, by which time he was a progressionist and grudging evolutionist. INTRODUCTION The Elgin fossil reptile Leptopleuron (Telerpeton) has been recognised in recent works by M. Bartholomew (1976) and P. J. Bowler (1976) as important in the early 1850s to Sir Charles Lyell's anti-progressionist stance. Long before the publication of Darwin's Origin, many palaeontologists viewed the history of life as progressive, and recognised a general trend towards more and more complex forms through time arising by a series of creations.