State of Bombay V. Laxman Sakharam Pimparkar, 1959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

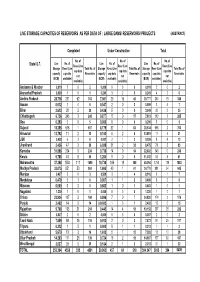

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

GRMB Annual Report 2017-18

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, RD & GR Godavari River Management Board ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 GODAVARI BASIN – Dakshina Ganga Origin Brahmagiri near Trimbakeshwar, Nasik Dist., Maharashtra Geographical Area 9.50 % of Total GA of India Area & Location Latitude - 16°19’ to 22°34’ North Longitude – 73°24’ to 83° 4’ East Boundaries West: Western Ghats North: Satmala hills, the Ajanta range and the Mahadeo hills East: Eastern Ghats & the Bay of Bengal South: Balaghat & Mahadeo ranges stretching forth from eastern flank of the Western Ghats & the Anantgiri and other ranges of the hills and ridges separate the Gadavari basin from the Krishna basin. Catchment Area 3,12,812 Sq.km Length of the River 1465 km States Maharashtra (48.6%), Telangana (18.8%), Andhra Pradesh (4.5%), Chhattisgarh (10.9%), Madhya Pradesh (10.0%), Odisha (5.7%), Karnataka (1.4%) and Puducherry (Yanam) and emptying into Bay of Bengal Length in AP & TS 772 km Major Tributaries Pravara, Manjira, Manair – Right side of River Purna, Pranhita, Indravati, Sabari – Left side of River Sub- basins Twelve (G1- G12) Dams Gangapur Dam, Jayakwadi dam, Vishnupuri barrage, Ghatghar Dam, Upper Vaitarna reservoir, Sriram Sagar Dam, Dowleswaram Barrage. Hydro power stations Upper Indravati 600 MW Machkund 120 MW Balimela 510 MW Upper Sileru 240 MW Lower Sileru 460 MW Upper Kolab 320 MW Pench 160 MW Ghatghar pumped storage 250 MW Polavaram (under 960 MW construction) ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 GODAVARI RIVER MANAGEMENT BOARD 5th Floor, Jalasoudha, Errum Manzil, Hyderabad- 500082 FROM CHAIRMAN’S DESK It gives me immense pleasure to present the Annual Report of Godavari River Management Board (GRMB) for the year 2017-18. -

Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI, DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. †919 ANSWERED ON 27.06.2019 OLDER DAMS †919. SHRI HARISH DWIVEDI Will the Minister of JAL SHAKTI be pleased to state: (a) the number and names of dams older than ten years across the country, State-wise; (b) whether the Government has conducted any study regarding safety of dams; and (c) if so, the outcome thereof? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE FOR JAL SHAKTI & SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (SHRI RATTAN LAL KATARIA) (a) As per the data related to large dams maintained by Central Water Commission (CWC), there are 4968 large dams in the country which are older than 10 years. The State-wise list of such dams is enclosed as Annexure-I. (b) to (c) Safety of dams rests primarily with dam owners which are generally State Governments, Central and State power generating PSUs, municipalities and private companies etc. In order to supplement the efforts of the State Governments, Ministry of Jal Shakti, Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation (DoWR,RD&GR) provides technical and financial assistance through various schemes and programmes such as Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Programme (DRIP). DRIP, a World Bank funded Project was started in April 2012 and is scheduled to be completed in June, 2020. The project has rehabilitation provision for 223 dams located in seven States, namely Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Tamil Nadu and Uttarakhand. The objectives of DRIP are : (i) Rehabilitation and Improvement of dams and associated appurtenances (ii) Dam Safety Institutional Strengthening (iii) Project Management Further, Government of India constituted a National Committee on Dam Safety (NCDS) in 1987 under the chairmanship of Chairman, CWC and representatives from State Governments with the objective to oversee dam safety activities in the country and suggest improvements to bring dam safety practices in line with the latest state-of-art consistent with Indian conditions. -

Vidal Network Hospital List ‐ All Over India Page ‐ 1 of 603 Pin State City Hospital Name Address Phone No

PIN STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PHONE NO. CODE D.No.29‐14‐45, Sri Guru Residency, Prakasam Road, Suryaraopet, Andhra Pradesh Achanta Amaravati Eye Hospital Pushpa Hotel Centre, Vijayawada 520002 0866‐2437111 Konaseema Institute Of Medical Sciences Nh‐241, Chaitanya Nagar, From Andhra Pradesh Amalapuram & Research Foundation Rajamundry To Kakinada By Road 533201 08856‐237996 Andhra Pradesh Amalapuram Srinidhi Hospitals No. 3‐2‐117E, Knf Road 533201 08856‐232166 Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Aasha Hospitals 7‐201, Court Road 515001 08854‐274194 12‐2‐950(12‐358)Sai Nager 2Nd Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Baby Hospital Cross 515001 08554‐237969 #15‐455, Near Srs Lodge, Kamala Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Balaji Eye Care & Laser Centre Nagar 515001 040‐66136238 Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Dr Ysr Memorial Hospital #12‐2‐878, 1Cross, Sai Nagar 515001 08554‐247155 Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Dr. Akbar Eye Hospital #12‐3‐2 346Th Lane Sai Nagar 515001 08554‐235009 Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Jeevana Jyothi Hospital #15/381, Kamala Nagar 515001 08554‐249988 15/721, Munirathnam Transport, Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Mythri Hospital Kamalanagar 515001 08554‐274630 D.No. 13‐3‐510, Opp: Ganga Gowri Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Snehalatha Hospitals Cine Complex, Khaja Nagar 515001 08554‐277077 13‐3‐488, Near Ganga‐Gowri Cine Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Sreenivasa Childrens Hospital Complex 515001 0855‐4241104 Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Sri Sai Krupa Nursing Home 10/368, New Sarojini Road 515001 08554‐274564 Andhra Pradesh Ananthapur Vasan Eye Care Hospital‐Anantapur #15/581, Raju Road 515001 08554‐398900 Undi Road, Near Town Railway Andhra Pradesh Bhimavaram Krishna Hospital Station 534202 08816‐227177 Andhra Pradesh Bhimavaram Sri Kanakadurga Nursing Home Juvvalapalem Road, J.P Road 534202 08816‐223635 VIDAL NETWORK HOSPITAL LIST ‐ ALL OVER INDIA PAGE ‐ 1 OF 603 PIN STATE CITY HOSPITAL NAME ADDRESS PHONE NO. -

GRMB Annual Report 2016-17

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Godavari River Management Board, Hyderabad ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 GODAVARI RIVER MANAGEMENT BOARD th 5 Floor, Jalasoudha, ErrumManzil, Hyderabad- 500082 PREFACE It is our pleasure to bring out the first Annual Report of the Godavari River Management Board (GRMB) for the year 2016-17. The events during the past two years 2014-15 and 2015-16 after constitution of GRMB are briefed at a glance. The Report gives an insight into the functions and activities of GRMB and Organisation Structure. In pursuance of the A.P. Reorganization Act, 2014, Central Government constituted GRMB on 28th May, 2014 with autonomous status under the administrative control of Central Government. GRMB consists of Chairperson, Member Secretary and Member (Power) appointed by the Central Government and one Technical Member and one Administrative Member nominated by each of the Successor State. The headquarters of GRMB is at Hyderabad. GRMB shall ordinarily exercise jurisdiction on Godavari river in the States of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh in regard to any of the projects over head works (barrages, dams, reservoirs, regulating structures), part of canal network and transmission lines necessary to deliver water or power to the States concerned, as may be notified by the Central Government, having regard to the awards, if any, made by the Tribunals constituted under the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956. During the year 2016-17, GRMB was headed by Shri Ram Saran, as the Chairperson till 31st December, 2016, succeeded by Shri S. K. Haldar, Chief Engineer, NBO, CWC, Bhopal as in-charge Chairperson from 4th January, 2017. -

11.1.04. Comprehensive Study Report for Godavari

Draft Report COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF POLLUTED RIVER STRETCHES AND PREPARATION OF ACTION PLAN OF RIVER GODAVARI FROM NASIK D/S TO PAITHAN Funded by Submitted by Aavanira Biotech P. Ltd. Kinetic Innovation Park, D-1 Block, Plot No. 18/1, MIDC Chinchwad, Pune 411 019, Maharashtra, India, Email: [email protected], Web: www.aavanira.com March 2015 1 INDEX Chapter Contents Page Numbers 7 1 Introduction 1.1 Importance of Rivers 8 1.2 Indian Rivers 8 1.3 River Godavari and its Religious Significance 8 1.4 Salient Features of Godavari Basin 9 1.5 Geographical Setting of River Godavari 11 1.6 Godavari River System 12 1.7 Demography of River Godavari 13 1.8 Status of Rivers in India 14 1.9 River Water Quality Monitoring and River Conservation 14 2 Methodology of Survey 16 2.1 Background of the Study 17 2.2 Methodology 17 2.2.1 Primary Data Generation 18 2.2.2 Secondary Data Generation 19 2.3 Identification of Polluted River Stretches 19 2.4 Statistical Analysis 21 3 Study Area 22 3.1 Background of Present Study 23 3.2 Selection of Sampling Locations 23 3.3 Geographical Setting of Polluted River Stretches 24 3.4 Major Cities/ Towns on Polluted River Stretches 28 3.5 An insight of the Cities/ Towns Located of Polluted River 28 Stretches of Godavari from Nasik D/s to Paithan 3.6 Villages on the Banks of River Godavari 32 4 Observation 40 4.1 Observations of Polluted Stretches 41 4.1.1 U/s of Gangapur Dam, Nasik 41 4.1.2 D/s of Gangapur Dam to Someshwar Temple 42 4.1.3 Someshwar Temple to Hanuman Ghat 43 4.1.4 Hanuman Ghat to Panchavati at Ramkund 44 -

In the Supreme Court of India

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA ORIGINAL JURISDICTION ORIGINAL SUIT NO. 1 OF 2006 State of Andhra Pradesh …… Plaintiff Vs. State of Maharashtra & Ors. …… Defendants WITH WRIT PETITION [C] NO. 134 OF 2006 WRIT PETITION [C] NO. 210 OF 2007 WRIT PETITION [C] NO. 207 OF 2007 AND CONTEMPT PETITION [C] NO. 142 OF 2009 IN ORIGINAL SUIT NO. 1 OF 2006 JUDGMENT R.M. LODHA, J. Original Suit No. 1 of 2006 Two riparian states – Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra – of the inter-state Godavari river are principal parties in the suit filed under Article 131 of the Constitution of India read with Order XXIII Rules 1,2 and 3 of the Supreme Court Rules, 1966. The suit has been filed by Andhra Pradesh (Plaintiff) complaining violations by Maharashtra (1st Defendant) of the 1 Page 1 agreements dated 06.10.1975 and 19.12.1975 which were endorsed in the report dated 27.11.1979 containing decision and final order (hereafter to be referred as “award”) and further report dated 07.07.1980 (hereafter to be referred as “further award) given by the Godavari Water Disputes Tribunal (for short, ‘Tribunal’). The violations alleged by Andhra Pradesh against Maharashtra are in respect of construction of Babhali barrage into their reservoir/water spread area of Pochampad project. The other four riparian states of the inter-state Godavari river – Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Orissa have been impleaded as 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th defendant respectively. Union of India is 2nd defendant in the suit. 2. The Godavari river is the largest river in Peninsular India and the second largest in the Indian Union. -

Study on Coastal Road Development in Godavari Basins in Telangana

ISSN(Online): 2319-8753 ISSN (Print): 2347-6710 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (A High Impact Factor, Monthly, Peer Reviewed Journal) Visit: www.ijirset.com Vol. 7, Issue 11, November 2018 Study on Coastal Road Development in Godavari Basins in Telangana K.Karthik Reddy, V.Naveen M.Tech, Department of Transportation, Arjun College of Technology & Sciences, Mount Opera Premises, Batasingaram (V), (M), Hayathnagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India Assistant professor, Arjun College of Technology & Sciences, Mount Opera Premises, Batasingaram (V), (M), Hayathnagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India ABSTRACT: Coastal lands around Bay of Bengal in Central Godavari Delta are mainly agriculture fields and two times annually paddy crops putting in the study area. Canals of Godavari River are the main source of water for irrigation. Geophysical and geochemical investigations were carried out in the study area to decipher subsurface geologic formation and assessing seawater intrusion. Electrical resistivity tomographic surveys carried out in the watershed-indicated low resistivity formation in the upstream area due to the presence of thick marine clays up to thickness of 20–25 m from the surface. Secondly, the lowering of resistivity may be due to the encroachment of seawater in to freshwater zones and infiltration during tidal fluctuation through mainly the Pikaleru drain, and to some extent rarely through Kannvaram and Vasalatippa drains in the downstream area. Groundwater quality analyses were made for major ions revealed brackish nature of groundwater water at shallow depththe fossiliferous limestone bed is a representative horizon for the K-T boundary mass extinction caused due to intense volcanism. Inter trappean sediments exhibit weathered soil profiles (palaeosols) with limestone beds denoting a distinct time gap during various phases of lava eruption. -

July-Sept 2015 Pdf.Cdr

Chapter - 1 The Study Area INTRODUCTION GENERAL INFORMATION OF THE STUDY AREA : Nashik District lying between 19° 35' and 20° 52' north latitude and 73° 16' and 74° 56' east latitude, with an area of 15,582.0 km^ (6,015 sq.miles) has a population of 49,93,796 with 18 towns and 792 inhabited villages and 1136 uninhibited villages as per the sensus of 2001. Rhomboidal in shape with the longer diagonal about 170 km. From south west to north east and an extreme breadth of about 170 km. From north to south, Nasik is bounded on the north west by the Dangs and Surat district of Gujrath state, on the north by the Dhulia district, on the east by Jalgaon and Aurangabad districts, on the south by Ahmednagar district and towards the south west by Thana district (Map 1). The district derives its name from that of its headquarters town of Nasik, for the origin of which two interpretations are given. The town is sited on the nine peaks or NAVASHIKHARA and hence its name. The other relates to incident in the Ramayana, where at this place Laxamana is said to have cut off the nose (NASIKA) of Shurpanakha. Nasik is situated on the bank of the rivers and hills. Anjaneri hill is a fine mass of trap rock, with lofty upper and lower scraps, each resting on wild and well wooded plateau. From Anjeneri hill there is a spur extending southwards for about 3 km. From which three branches spurs resembling a trishul, which extends beyond the Dama river and its headwater streams are to be found three ranges radiating in irregular curves from the Saihyadri bordering another river Vaitarna. -

Part I Chapter I I N T R O D U C T I

PART I CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I . statement of Problem Many industrially developed and developing countries have faced and have been facing, in their economic develop ment, the problem of regional imbalance. To-day, India is also facing the same problem. Apart from being indus trially an under-developed country, India exhibits all the evils of mal-distribution and acute concentration of industrial activity since long. In the year 19U3» about 2/5th of the industrial activity of the country was con centrated in only two centres - Greater Bombay and Greater Calcutta. ^ Regional imbalanceis caused by a number of factors, both natural and historical. Some areas are naturally richer and advantageous than others because of the availability of natural resources and infra-structure facilities. Naturally those areas attract concentration of industries. In a country like India, all these factors vary from area to area and ultimately cause the imbalance in economic and industrial development of the country. It is also possible to explain this element of re gional imbalance with reference to the historical back ground. Under the British rule, the managing agents pioneered and developed certain industries in our country. But being foreigners they were not really interested in 1 Census of Manufacturing Industries in India, 1952 the many sided development of this country. Vhat was uppermost in their mind was the interest of their own country. They treated India more as a colony supplying the necessary raw materials to the Industries in Great Britain. As a rssult of this, they failed to develop in dustries in different parts of the couotry. -

Impact of Physical and Sociox

Impact of physical and socio-economical factors on agricultural scenario of Nashik District (MS) 1991 – 2011 A thesis submitted to, Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) In Department of earth Science (Geography) Under the board of Faculty of Moral and Social Science studies Submitted By Pandurang Dnyanadev Yadav Under The Guidance of Dr. Nanasaheb R. Kapadnis February 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “IMPACT OF PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMICAL FACTORS ON AGRICULTURAL SCENARIO OF NASHIK DISTRICT (M.S.) 1991 to 2011.” completed and written by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. (PANDURANG DNYANADEV YADAV) ResearchStudent Place: Pune Date: February,2016. I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “IMPACT OF PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMICAL FACTORS ON AGRICULTURAL SCENARIO OF NASHIK DISTRICT (M.S.) 1991 to 2011.”Which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in Earth Science (Geography) of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Pandurang Dnyanadev Yadav under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body upon him. (DR. NANASAHEB R. KAPADNIS) Research Guide Place: Pune Date: February, 2016. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express my deep sense of gratitude and sincere feelings to Dr. -

Faculty Profile

Kalwan Education Society’s Arts, Commerce and Science College, Kalwan (Manur) Tal: Kalwan Dist: Nashik FACULTY PROFILE Name : Mr. Sahebrao Jagannath Pawar Date of Birth : 01/06/1967 Field of specialization : Zoology (Entomology Physiology) Address for communication : Kulswamini Colony,Jagannath Banglow, Ganesh Nagar, Kalwan Tal. Kalwan Dist. Nashik Email : [email protected] Mobile : 9423255068 ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: (only UG, PG and Ph.D.) Degree University / Institution Grade / % Year of Passing Specialization B.Sc. Savitribai Fule Pune 65% 1st Class April/May 1988 Zoology University, Pune M.Sc. Savitribai Fule Pune 64.% 1st Class March 1992 Entomology University, Pune M.Sc. Y.C.M.O.U. Nashik 68% First Class 2015 Communication- Physics Ph.D. Dr. B.A. Marathawada NA 2 nd November 2017 Parasitology University Aurangabad EXPERIENCE: Name & Address of Employer Post Held Period of service Arts,Commerceand Science College, Kalwan (Manur) Assistant 28/08/1993 To 2018 Professor Total : 25 Years REFRESHER/ORIENTATION COURSES COMPLETED: - Details of Course Duration Orientation - Savitribai Fule Pune University, Pune 03/09/1996 to 30/09/1996 Refresher : Dr. B.A. Marathawada University Aurangabad 02/11/1998 to 30/11/1998 Subject Communication : Yashwantrao Chavan Open 2 Year Course, April 2015 University, Nashik REASEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT 1. PUBLICATIONS IN JOURNALS No. Title of the paper / Authors Journal 1 Acute Toxicity of Indo-Sulpin to a fresh water gastropod Thira IOSR Journal of Lineate changes in Rate reapiration : Dr. S.J.Pawar