Species Assessment for Gray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crows and Ravens Wildlife Notes

12. Crows & Ravens Crows and ravens belong to the large family Corvidae, along with more than 200 other species including jays, nutcrackers and magpies. These less-than-melodious birds, you may be surprised to learn, are classified as songbirds. raven American Crow insects, grain, fruit, the eggs and young of other birds, Crows are some of the most conspicuous and best known organic garbage and just about anything that they can find of all birds. They are intelligent, wary and adapt well to or overpower. Crows also feed on the carcasses of winter – human activity. As with most other wildlife species, crows and road-killed animals. are considered to have “good” points and “bad” ones— value judgements made strictly by humans. They are found Crows have extremely keen senses of sight and hearing. in all 50 states and parts of Canada and Mexico. They are wary and usually post sentries while they feed. Sentry birds watch for danger, ready to alert the feeding birds with a sharp alarm caw. Once aloft, crows fly at 25 Biology to 30 mph. If a strong tail wind is present, they can hit 60 Also known as the common crow, an adult American mph. These skillful fliers have a large repertoire of moves crow weighs about 20 ounces. Its body length is 15 to 18 designed to throw off airborne predators. inches and its wings span up to three feet. Both males Crows are relatively gregarious. Throughout most of the and females are black from their beaks to the tips of their year, they flock in groups ranging from family units to tails. -

A Fossil Scrub-Jay Supports a Recent Systematic Decision

THE CONDOR A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY Volume 98 Number 4 November 1996 .L The Condor 98~575-680 * +A. 0 The Cooper Omithological Society 1996 g ’ b.1 ;,. ’ ’ “I\), / *rs‘ A FOSSIL SCRUB-JAY SUPPORTS A”kECENT ’ js.< SYSTEMATIC DECISION’ . :. ” , ., f .. STEVEN D. EMSLIE : +, “, ., ! ’ Department of Sciences,Western State College,Gunnison, CO 81231, ._ e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Nine fossil premaxillae and mandibles of the Florida Scrub-Jay(Aphelocoma coerulescens)are reported from a late Pliocene sinkhole deposit at Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Vertebrate biochronologyplaces the site within the latestPliocene (2.0 to 1.6 million yearsago, Ma) and more specificallyat 2.0 l-l .87 Ma. The fossilsare similar in morphology to living Florida Scrub-Jaysin showing a relatively shorter and broader bill compared to western species,a presumed derived characterfor the Florida species.The recent elevation of the Florida Scrub-Jayto speciesrank is supported by these fossils by documenting the antiquity of the speciesand its distinct bill morphology in Florida. Key words: Florida; Scrub-Jay;fossil; late Pliocene. INTRODUCTION represent the earliest fossil occurrenceof the ge- nus Aphelocomaand provide additional support Recently, the Florida Scrub-Jay (Aphelocoma for the recognition ofA. coerulescensas a distinct, coerulescens) has been elevated to speciesrank endemic specieswith a long fossil history in Flor- with the Island Scrub-Jay(A. insularis) from Santa ida. This record also supports the hypothesis of Cruz Island, California, and the Western Scrub- Pitelka (195 1) that living speciesof Aphefocoma Jay (A. californica) in the western U. S. and Mex- arose in the Pliocene. ico (AOU 1995). -

Magpie Jay General Information and Care

Magpie Jay General Information and Care: Black Throated Magpie Jays (Calocitta colliei) and White Throated Magpie Jay (Calocitta formosa) are the only two species in their genus. Black Throated Magpie Jays are endemic to Northwestern Mexico. The range of White Throated Magpie Jays lies to the south, overlapping with Black Throats slightly in the Mexican states of Jalisco and Colima, and running into Costa Rica. Both of these birds are members of the family Corvidae. Magpie Jays are energetic, highly intelligent animals and need to be kept in a large planted aviary - not just a cage. These birds are highly social and are commonly found in the wild as cooperative nesters. They are omnivores and favor a great variety of fruits, insects, small rodents, and nuts. A captive diet that works well in my aviaries is a basic pellet low iron softbill diet such as Kaytee’s Exact Original Low Iron Maintenance Formula for Toucans, Mynas and other Softbills. A bowl of this is in the cage at all times and is supplemented with nuts, fruits and veggies like apples, papaya, grapes, oranges, peas and carrots and the occasional treat of small mice and insects like meal worms, crickets, megaworms, and waxworms are relished by the birds. Extra protein is essential if you want these birds to breed. Fresh water should always be provided. I use a shallow three to four inch deep, twelve inch wide crock the birds can drink from and bath in. The birds you are receiving from my aviaries are hand fed and closed banded. How recently they were weaned will affect how tame they are at first. -

S Largest Islands: Scenarios for the Role of Corvid Seed Dispersal

Received: 21 June 2017 | Accepted: 31 October 2017 DOI: 10.1111/1365-2664.13041 RESEARCH ARTICLE Oak habitat recovery on California’s largest islands: Scenarios for the role of corvid seed dispersal Mario B. Pesendorfer1,2† | Christopher M. Baker3,4,5† | Martin Stringer6 | Eve McDonald-Madden6 | Michael Bode7 | A. Kathryn McEachern8 | Scott A. Morrison9 | T. Scott Sillett2 1Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA; 2Migratory Bird Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, USA; 3School of BioSciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic., Australia; 4School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 5CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, Ecosciences Precinct, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 6School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, Qld, Australia; 7ARC Centre for Excellence for Coral Reefs Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld, Australia; 8U.S. Geological Survey- Western Ecological Research Center, Channel Islands Field Station, Ventura, CA, USA and 9The Nature Conservancy, San Francisco, CA, USA Correspondence Mario B. Pesendorfer Abstract Email: [email protected] 1. Seed dispersal by birds is central to the passive restoration of many tree communi- Funding information ties. Reintroduction of extinct seed dispersers can therefore restore degraded for- The Nature Conservancy; Smithsonian ests and woodlands. To test this, we constructed a spatially explicit simulation Institution; U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Grant/Award Number: DEB-1256394; model, parameterized with field data, to consider the effect of different seed dis- Australian Reseach Council; Science and persal scenarios on the extent of oak populations. We applied the model to two Industry Endowment Fund of Australia islands in California’s Channel Islands National Park (USA), one of which has lost a Handling Editor: David Mateos Moreno key seed disperser. -

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty About the Past Against Uncertainty About the Future in Channel Islands National Park

A Bird in Our Hand: Weighing Uncertainty about the Past against Uncertainty about the Future in Channel Islands National Park Scott A. Morrison Introduction Climate change threatens many species and ecosystems. It also challenges managers of protected areas to adapt traditional approaches for setting conservation goals, and the phil- osophical and policy framework they use to guide management decisions (Cole and Yung 2010). A growing literature discusses methods for structuring management decisions in the face of climate-related uncertainty and risk (e.g., Polasky et al. 2011). It is often unclear, how- ever, when managers should undertake such explicit decision-making processes. Given that not making a decision is actually a decision with potentially important implications, what should trigger management decision-making when threats are foreseeable but not yet mani- fest? Conservation planning for the island scrub-jay (Aphelocoma insularis) may warrant a near-term decision about non-traditional management interventions, and so presents a rare, specific case study in how managers assess uncertainty, risk, and urgency in the context of climate change. The jay is restricted to Santa Cruz Island, one of the five islands within Chan- nel Islands National Park (CINP) off the coast of southern California, USA. The species also once occurred on neighboring islands, though it is not known when or why those populations went extinct. The population currently appears to be stable, but concerns about long-term viability of jays on Santa Cruz Island have raised the question of whether a population of jays should be re-established on one of those neighboring islands, Santa Rosa. -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

The Puzzling Vocal Repertoire of the South American Collared Jay, Cyanolyca Iridicyana Merida

THE PUZZLING VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN COLLARED JAY, CYANOLYCA VZRIDZCYANA MERIDA JOHN WILLIAM HARDY Previously, I have indicated (Kansas Sci. Bull., 42: 113, 1961) that the New World jays could be systematically grouped in two tribes on the basis of a variety of morphological and behavioral characteristics. I subsequently demonstrated (Occas. Papers Adams Ctr. Ecol. Studies, No. 11, 1964) the relationships between Cyanolyca and Aphelocoma. The tribe Aphelocomini, comprising the currently recognized genera Aphelocoma and Cyanolyca, may be characterized as follows: pattern and ornamen- tation of head simple, consisting of a dark mask, pale superciliary lineation, and no tendency for a crest; tail plain-tipped; vocal repertoire of one to three basic com- ponents, including alarm calls, flock-social calls, or both, that are nasal, querulous, and upwardly or doubly inflected. In contrast, the Cyanocoracini may be charac- tized as follows: pattern of head complex, consisting of triangular cheek patch, super- ciliary spot, and tendency for a crest; tail usually pale-tipped; vocal repertoire usu- ally complex, commonly including a downwardly inflected cuwing call and never an upwardly inflected, nasal querulous call (when repertoire is limited it almost always includes the cazo!ingcall). None of the four Mexican aphelocomine jays has more than three basic calls in its vocal repertoire. There are two exclusively South American species of CyanuZyca (C. viridicyana and C. pulchra). On the basis of the consistency with which the Mexican and Central American speciesof this genus hew to a general pattern of vocalizations as I described it for the tribe, I inferred (1964 op. -

The White-Throated Magpie-Jay

THE WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE-JAY BY ALEXANDER F. SKUTCH ORE than 15 years have passed since I was last in the haunts of the M White-throated Magpie-Jay (Calocitta formosa) . During the years when I travelled more widely through Central America I saw much of this bird, and learned enough of its habits to convince me that it would well repay a thorough study. Since it now appears unlikely that I shall make this study myself, I wish to put on record such information as I gleaned, in the hope that these fragmentary notes will stimulate some other bird- watcher to give this jay the attention it deserves. A big, long-tailed bird about 20 inches in length, with blue and white plumage and a high, loosely waving crest of recurved black feathers, the White-throated Magpie-Jay is a handsome species unlikely to be confused with any other member of the family. Its upper parts, including the wings and most of the tail, are blue or blue-gray with a tinge of lavender. The sides of the head and all the under plumage are white, and the outer feathers of the strongly graduated tail are white on the terminal half. A narrow black collar crosses the breast and extends half-way up each side of the neck, between the white and the blue. The stout bill and the legs and feet are black. The sexes are alike in appearance. The species extends from the Mexican states of Colima and Puebla to northwestern Costa Rica. A bird of the drier regions, it is found chiefly along the Pacific coast from Mexico southward as far as the Gulf of Nicoya in Costa Rica. -

Distribution Habitat and Social Organization of the Florida Scrub Jay

DISTRIBUTION, HABITAT, AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE FLORIDA SCRUB JAY, WITH A DISCUSSION OF THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATIVE BREEDING IN NEW WORLD JAYS BY JEFFREY A. COX A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1984 To my wife, Cristy Ann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank, the following people who provided information on the distribution of Florida Scrub Jays or other forms of assistance: K, Alvarez, M. Allen, P. C. Anderson, T. H. Below, C. W. Biggs, B. B. Black, M. C. Bowman, R. J. Brady, D. R. Breininger, G. Bretz, D. Brigham, P. Brodkorb, J. Brooks, M. Brothers, R. Brown, M. R. Browning, S. Burr, B. S. Burton, P. Carrington, K. Cars tens, S. L. Cawley, Mrs. T. S. Christensen, E. S. Clark, J. L. Clutts, A. Conner, W. Courser, J. Cox, R. Crawford, H. Gruickshank, E, Cutlip, J. Cutlip, R. Delotelle, M. DeRonde, C. Dickard, W. and H. Dowling, T. Engstrom, S. B. Fickett, J. W. Fitzpatrick, K. Forrest, D. Freeman, D. D. Fulghura, K. L. Garrett, G. Geanangel, W. George, T. Gilbert, D. Goodwin, J. Greene, S. A. Grimes, W. Hale, F. Hames, J. Hanvey, F. W. Harden, J. W. Hardy, G. B. Hemingway, Jr., 0. Hewitt, B. Humphreys, A. D. Jacobberger, A. F. Johnson, J. B. Johnson, H. W. Kale II, L. Kiff, J. N. Layne, R. Lee, R. Loftin, F. E. Lohrer, J. Loughlin, the late C. R. Mason, J. McKinlay, J. R. Miller, R. R. Miller, B. -

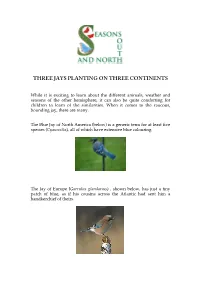

Three Jays Planting on Three Continents

THREE JAYS PLANTING ON THREE CONTINENTS While it is exciting to learn about the different animals, weather and seasons of the other hemisphere, it can also be quite comforting for children to learn of the similarities. When it comes to the raucous, bounding jay, there are many. The Blue Jay of North America (below) is a generic term for at least five species (Cyanocitta), all of which have extensive blue colouring. The Jay of Europe (Garrulus glandarius) , shown below, has just a tiny patch of blue, as if his cousins across the Atlantic had sent him a handkerchief of theirs. The Azure Jay (Cyanocorax caeruleus) of South America's Atlantic Rainforest (below) is like a regal relative with a deep blue cloak and a black hood. All are members of the crow family and it shows in their personalities. All are so well known for their habit of hiding seeds that they have become almost symbolic for it in each region. In late summer and early autumn when seeds from the great trees are falling, the jays on all three continents are greedy about trying to find as many seeds as possible to store. They hide them in logs, under leaves, in the earth, in anticipation of the lean times to come during the winter. Some they find later and eat; some they do not. Those they do not find often germinate and grow into trees. To people observing them, it seems as if they are intentionally planting the seeds and many stories about them doing so are told. In a time when forests are disappearing, reforestation has taken on urgency and almost a sacredness. -

Acorn Dispersal by California Scrub-Jays in Urban Sacramento, California Daniel A

ACORN DISPERSAL BY CALIFORNIA SCRUB-JAYS IN URBAN SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA DANIEL A. AIROLA, Conservation Research and Planning, 114 Merritt Way, Sac- ramento, California 95864; [email protected] ABSTRACT: California Scrub-Jays (Aphelocoma californica) harvest and cache acorns as a fall and winter food resource. In 2017 and 2018, I studied acorn caching by urban scrub-jays in Sacramento, California, to characterize oak and acorn resources, distances jays transport acorns, caching’s effects on the jay’s territoriality, numbers of jays using acorn sources, and numbers of acorns distributed by jays. Within four study areas, oak canopy cover was <1%, and only 19% of 126 oak trees, 92% of which were coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), produced acorns. Jays transported acorns for ≥117 days. Complete (28%) and partially recorded (72%) flights from acorn sources to caching sites averaged 160 m and ranged up to 670 m. Acorn- transporting jays passed at tree-top level above other jays’ territories without eliciting defense. At least 20 scrub-jays used one acorn source in one 17.5-ha area, and ≥13 jays used another 4.7-ha area. Jays cached an estimated 6800 and 11,000 acorns at two study sites (mean 340 and 840 acorns per jay, respectively), a rate much lower than reported in California oak woodlands, where harvest and caching are confined within territories. The lower urban caching rate may result from a scarcity of acorns, the time required for transporting longer distances, and the availability of alternative urban foods. Oaks originating from acorns planted by jays benefit diverse wildlife and augment the urban forest. -

Blue Jay Cyanocitta Cristata Adult ILLINOIS RANGE

blue jay Cyanocitta cristata Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The blue jay averages 11 to12 inches in length. It is a Class: Aves large bird with blue feathers and a crest. White Order: Passeriformes feather patches are present in the wings and tail. A black line behind the head extends from each side Family: Corvidae to form a black “necklace” on the throat. This bird ILLINOIS STATUS has white or gray feathers underneath. common, native BEHAVIORS The blue jay is a common, permanent resident statewide in Illinois. However, blue jays do migrate within Illinois, moving to southern Illinois from the northern sections of the state in the winter. The nesting season lasts from April through mid-July. The nest is built in a forest, residential area, orchard or other location where trees are present, from five to 50 feet above the ground. Both sexes construct the nest of twigs, bark, leaves, mosses and string and line it with rootlets. Four or five olive, tan or blue- green eggs with dark markings are laid. Both the male and female take turns incubating the eggs over a 17- to 18-day period. One brood is raised per year. This aggressive bird uses its loud calls (“jay,” “jeeah,” adult “queedle, queedle”) to alert others to possible danger. The blue jay can mimic some other birds, too. It may go to roost in mid-afternoon in the winter months. Found in woodlands and residential ILLINOIS RANGE areas, the blue jay eats nuts, particularly acorns, corn, fruits, insects and dead animals. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources.