A Short Prehistory of Western Music, Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Comparative Analysis of the Melody in the Kṛti Śhri

Comparative analysis of the melody in the Kṛti Śri Mahāgaṇapatiravatumām with references to Saṅgīta Sampradāya Pradarśini of Subbarāma Dīkṣitar and Dīkṣita Kīrtana Mālā of A. Sundaram Ayyar Pradeesh Balan PhD-JRF Scholar (full-time) Department of Music Queen Mary‟s College Chennai – 600 004 Introduction: One of the indelible aspects of music when it comes to passing on to posterity is the variations in renditions, mainly since the sources contain not only texts of songs and notations but also an oral inheritance. This can be broadly witnessed in the compositions of the composers of Carnatic Music. Variations generally occur in the text of the song, rāga, tāḷa, arrangement of the words within the tāḷa cycle and melodic framework, graha, melodic phrases and musical prosody1. The scholars who have written and published on Muttusvāmi Dīkṣitar and his accounts are named in chronological order as follows: Subbarāma Dīkṣitar Kallidaikuricci Ananta Krishṇa Ayyar Natarāja Sundaram Pillai T. L. Venkatarāma Ayyar Dr. V. Rāghavan A. Sundaram Ayyar R. Rangarāmānuja Ayyengār Prof. P. Sāmbamūrthy Dr. N. Rāmanāthan writes about Śri Māhādēva Ayyar of Kallidaikuricci thus: He is a student of Kallidaikuricci Vēdānta Bhāgavatar and along with A. Anantakṛṣṇayyar (well known as Calcutta Anantakṛṣṇa Ayyar) and A. Sundaram Ayyar (of Mayilāpūr), has been instrumental in learning the compositions of Dīkṣitar from Śri Ambi Dīkṣita, son of Subbarāma Dīkṣita and propagating them to the next generation2. Dr. V. Rāghavan (pp. 76-92), in his book Muttuswāmi Dīkṣitar gives an index of Dīkṣitar‟s compositions which is forked in two sections. The former section illustrates the list of kṛti-s as notated in Saṅgīta Sampradāya Pradarśini of Subbarāma Dīkṣitar while the other one lists almost an equal number of another set 1 Rāmanāthan N. -

B.A.Western Music School of Music and Fine Arts

B.A.Western Music Curriculum and Syllabus (Based on Choice based Credit System) Effective from the Academic Year 2018-2019 School of Music and Fine Arts PROGRAM EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES (PEO) PEO1: Learn the fundamentals of the performance aspect of Western Classical Karnatic Music from the basics to an advanced level in a gradual manner. PEO2: Learn the theoretical concepts of Western Classical music simultaneously along with honing practical skill PEO3: Understand the historical evolution of Western Classical music through the various eras. PEO4: Develop an inquisitive mind to pursue further higher study and research in the field of Classical Art and publish research findings and innovations in seminars and journals. PEO5: Develop analytical, critical and innovative thinking skills, leadership qualities, and good attitude well prepared for lifelong learning and service to World Culture and Heritage. PROGRAM OUTCOME (PO) PO1: Understanding essentials of a performing art: Learning the rudiments of a Classical art and the various elements that go into the presentation of such an art. PO2: Developing theoretical knowledge: Learning the theory that goes behind the practice of a performing art supplements the learner to become a holistic practioner. PO3: Learning History and Culture: The contribution and patronage of various establishments, the background and evolution of Art. PO4: Allied Art forms: An overview of allied fields of art and exposure to World Music. PO5: Modern trends: Understanding the modern trends in Classical Arts and the contribution of revolutionaries of this century. PO6: Contribution to society: Applying knowledge learnt to teach students of future generations . PO7: Research and Further study: Encouraging further study and research into the field of Classical Art with focus on interdisciplinary study impacting society at large. -

Für Sonntag, 21

Tägliche BeatlesInfoMail 29.12.20: I want to tell you /// Zwei Mal THINGS 343 - jeweils auf Deutsch und Englisch /// MANY YEARS AGO ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Im Beatles Museum erhältlich: Zwei Mal THINGS 343 - jeweils auf Deutsch und Englisch Versenden wir gut verpackt als Brief (mit Deutscher Post). Abbildungen von links: Titelseite und Inhaltsverzeichnis für deutsches THINGS 343 / alle 40 Seiten (verkleinert) Deutsches BEATLES-Magazin THINGS 343. 4,00 € inkl. Versand Herausgeber: Beatles Museum, Deutschland. 1617-8114. Heft, A5-Format, 40 Seiten; viele Farb- und Schwarzweiß-Fotos; deutschsprachig. Schwerpunktthemen (mindestens eine Seite): MANY YEARS AGO: BEATLES-Aufnahmen für das Album RUBBER SOUL. / PAUL McCARTNEY, RINGO STARR, JOHN LENNON, GEORGE HARRISON 1970. / JOHN LENNON und YOKO ONO - Interviews und Fotos im Cafe La Fortuna, New York. / JOHN LENNON und YOKO ONO - die Kimono-Fotos. / GEORGE und OLIVIA HARRISON besuchen Christie’s in London. / GEORGE HARRISON produziert neues My Sweet Lord-Video. / RINGO STARR auf Veranstaltung IMAGINE THERE’S NO HUNGER. / NEWS & DIES & DAS: BADFINGER-Mitglied JOEY MOLLAND mit neuen Versionen von drei Songs und neuem BADFINGER-Album. / 1966er BEATLES-Auftritt beim „‘New Musical Express’ Poll Winners Concert“. / „Record Store Day 2020“-Veröffentlichungen mit BEATLES-Bezug. / Buch BEATLEMANIA - FOUR PHOTOGRAPHERS ON THE FAB FOUR. / PAUL McCARTNEY-Album McCARTNEY III. Kompletter Inhalt: Coverfoto: THE BEATLES am Mittwoch 3. November 1965 im EMI Recording Studio 2 beim Aufnehmen von Songs für das nächste Album, RUBBER SOUL. Angebot / Info: Buch/Fotoband ASTRID KIRCHHERR WITH THE BEATLES. Seite halb Vier: BEATLES CLUB WUPPERTAL trauert um Doris Schulte-Albrecht. Impressum: Infos zum Beatles Museum und zu THINGS. Hallo M.B.M., die nächsten 40 Jahre. -

Transcription and Analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love For

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Transcription and analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love for Western flute, sitar, tabla and tanpura Bethany Padgett Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Padgett, Bethany, "Transcription and analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love for Western flute, sitar, tabla and tanpura" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 511. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/511 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF RAVI SHANKAR’S MORNING LOVE FOR WESTERN FLUTE, SITAR, TABLA AND TANPURA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Bethany Padgett B.M., Western Michigan University, 2007 M.M., Illinois State University, 2010 August 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am entirely indebted to many individuals who have encouraged my musical endeavors and research and made this project and my degree possible. I would first and foremost like to thank Dr. Katherine Kemler, professor of flute at Louisiana State University. She has been more than I could have ever hoped for in an advisor and mentor for the past three years. -

301763 Communityconnections

White Paper, p. 2 White Paper The Connected Community: Local Governments as Partners in Citizen Engagement and Community Building James H. Svara and Janet Denhardt, Editors Arizona State University October 15, 2010 Reprinting or reuse of this document is subject to the “Fair Use” principal. Reproduction of any substantial portion of the document should include credit to the Alliance for Innovation. Cover Image, Barn Raising, Paul Pitt Used with permission of Beverly Kaye Gallery Art.Brut.com White Paper, p. 3 Table of Contents The Connected Community, James Svara and Janet Denhardt Preface, p. 4 Overview: Citizen Engagement, Why and How?, p. 5 Citizen Engagement Strategies, Approaches, and Examples, p. 28 References, p. 49 Essays General Discussions Cheryl Simrell King, “Citizen Engagement and Sustainability.” p. 52 John Clayton Thomas, “Citizen, Customer, Partner: Thinking about Local Governance with and for the Public.” p. 57 Mark D. Robbins and Bill Simonsen, “Citizen Participation: Goals and Methods.” p. 62 Utilizing the Internet and Social Media Thomas Bryer, “Across the Great Divide: Social Media and Networking for Citizen Engagement.” p. 73 Tina Nabatchi and Ines Mergel, “Participation 2.0: Using Internet and Social Media: Technologies to Promote Distributed Democracy and Create Digital Neighborhoods.” - p. 80 Nancy C. Roberts, “Open-Source, Web-Based Platforms for Public Engagement during Disasters.” p. 88 Service Delivery and Performance Measurement Kathe Callahan, “Next Wave of Performance Measurement: Citizen Engagement,” p. 95 Janet Woolum, “Citizen-Government Dialogue in Performance Measurement Cycle: Cases from Local Government.” p. 102 Arts Applications Arlene Goldbard, “The Art of Engagement: Creativity in the Service of Citizenship.” p. -

The Royal Irish Academy of Music Local Centre Exams Piano Syllabus 2019

THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY OF MUSIC LOCAL CENTRE EXAMS PIANO SYLLABUS 2019–2022 REVISED WITH CORRECTIONS, OCTOBER 2019 EXAM TIMINGS GRADES RECITAL CERTIFICATE THEORY AND HARMONY Elementary, Preliminary, Primary, Grade I: Junior: 5–10 minutes Preparatory: 1 hour 10 minutes Grade II: 12 minutes Intermediate: 12–15 minutes Grades 1 and 2: 1 ½ hours Grade III: 15 minutes Advanced: 20–25 minutes Grades 3, 4, and 5: 2 hours Grades IV and V: 20 minutes DUETS Grades 6, 7, 8, and Senior Certificate: 3 hours Grades VI, VII, and VIII: 30 minutes Preparatory: 10 minutes Senior Certificate: 45 minutes Junior: 15 minutes Candidates who submit a special needs form are Intermediate and Senior: 20 minutes allocated additional time. Grades Graded exams consist of the performance of 3 pieces, scales & arpeggios, sight-reading, aural tests, and theory questions. From Grade VI–Senior Certificate, the aural and theoretical sections are combined. For senior certificate only, there is a brief viva voce section. All graded exams are marked out of 100. The pass mark is 60–69, pass with Merit 70–79, pass with Honours 80–89, and pass with Distinction 90+. Recital Certificate The recital exams consist of the performance of pieces only. A minimum of two pieces must be performed at Junior level, while a minimum of three pieces must be performed at the Intermediate and Advanced levels; it is important to note that more pieces may be necessary to meet the time requirement. The recital certificates are marked out of 100. The pass mark is 70–79 for the awarding of a bronze medal, 80–89 for a silver medal, and 90+ for a gold medal. -

9753 Y21 Sy Music H2 Level for 2021

Music Singapore-Cambridge General Certificate of Education Advanced Level Higher 2 (2021) (Syllabus 9753) CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 2 AIMS 2 FRAMEWORK 2 WEIGHTING AND ASSESSMENT OF COMPONENTS 3 ASSESSMENT OBJECTIVES 3 DESCRIPTION OF COMPONENTS 4 DETAILS OF TOPICS 10 ASSESSMENT CRITERIA 14 NOTES FOR GUIDANCE 22 Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board MOE & UCLES 2019 1 9753 MUSIC GCE ADVANCED LEVEL H2 SYLLABUS (2021) INTRODUCTION This syllabus is designed to engage students in music listening, performing and composing, and recognises that each is an individual with his/her own musical inclinations. This syllabus is also underpinned by the understanding that an appreciation of the social, cultural and historical contexts of music is vital in giving meaning to its study, and developing an open and informed mind towards the multiplicities of musical practices. It aims to nurture students’ thinking skills and musical creativity by providing opportunities to discuss music-related issues, transfer learning and to make music. It provides a foundation for further study in music while endeavouring to develop a life-long interest in music. AIMS The aims of the syllabus are to: • Develop critical thinking and musical creativity • Develop advanced skills in communication, interpretation and perception in music • Deepen understanding of different musical traditions in their social, cultural and historical contexts • Provide the basis for an informed and life-long appreciation of music FRAMEWORK This syllabus approaches the study of Music through Music Studies and Music Making. It is designed for the music student who has a background in musical performance and theory. Music Studies cover a range of works from the Western Music tradition as well as prescribed topics from the Asian Music tradition. -

The Tempo Indications of Mozart. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988

Performance Practice Review Volume 4 Article 14 Number 1 Spring "The eT mpo Indications of Mozart." By Jean-Pierre Marty Thomas Bauman Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Bauman, Thomas (1991) ""The eT mpo Indications of Mozart." By Jean-Pierre Marty," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 4: No. 1, Article 14. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199104.01.14 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol4/iss1/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jean-Pierre Marty. The Tempo Indications of Mozart. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988. xvi, 279,112p. Mozart's tempo indications have attracted something less than their fair share of scholarly and theoretical attention. Jean-Pierre Marty's comprehensive, painstaking study — the fruit of fifteen years' study and reflection — sallies with a happy blend of musicianly passion and Gallic sensibility into this sketchily surveyed terrain, mapping out problems and posing hypotheses, conjectures, and conclusions that reach across the entire span of Mozart's oeuvre. Every one of the composer's authenticated tempo indications has been pondered, weighed, and classified, and almost always with an ear to performative realities as well as an eye to systematic niceties. Marty's classificatory scheme is an ingenious one. Moreover, it takes full (or almost full) cognizance of the fact that what good musicians have meant by tempo is not simply velocity, either relative or absolute. -

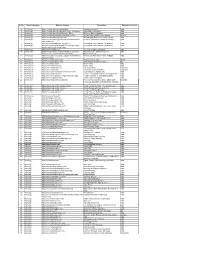

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V.