Market Structure, Liberalization and Performance in the Malawian Banking Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Bank Of

Report and Accounts 2010 RBM Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Reserve Bank of Malawi Reserve Bank of RESERVE BANK OF MALAWI REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2010 2 Report and Accounts RBM RESERVE BANK OF MALAWI REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2010 3 Report and Accounts 2010 RBM BOARD OF DIRECTORS Dr. Perks M. Ligoya Governor & Chairman of the Board Mrs Mary C. Nkosi Deputy Governor Mrs. Betty Mahuka Mr. Gautoni Kainja Mr. Joseph Mwanamveka Board Member Board Member Board Member Dr. Patrick Kambewa 4 Board Member Mr. Ted. Sitimawina Board Member Report and Accounts RBM MISSION STATEMENT As the central Bank of the Republic of Malawi, we are committed to promoting monetary stability and soundness of the financial system. In pursuing these goals, we shall endeavour to carry out our duties professionally and exclusively in the long-term interest of the national economy. To achieve this, we shall be a team of professionals dedicated to international standards in the delivery of our services. 5 Report and Accounts 2010 RBM EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT Dr. Perks M. Ligoya Governor Mrs. Mary C. Nkosi Deputy Governor Dr. Grant P. Kabango Acting General Manager, Economic Services 6 Report and Accounts RBM 7 Report and Accounts 2010 RBM HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS Banda, L. (Ms) Director, Banking and Payment Systems Chitsonga, D Director, Information and Communication Technology Chokhotho, R. Director, Human Resources Goneka, E. Director, Research and Statistics Kabango G.P. (Dr) Director, Special Duties Kajiyanike, M. (Ms) Director, Currency Management Malitoni, S. -

List of Participants As of 30 April 2013

World Economic Forum on Africa List of Participants As of 30 April 2013 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 9-11 May 2012 Messumbe Stanly Paralegal The ABENG Law Firm Cameroon Abane Yilkal Abate Secretary-General ICT Association of Ethiopia Ethiopia Zein Abdalla Chief Executive Officer PepsiCo Europe Switzerland Amin Abdulkader Minister of Culture and Tourism of Ethiopia Rakeb Abebe Chief Executive Officer and Founder GAWT International Business Ethiopia Plc Olufemi Adeyemo Group Chief Financial Officer Oando Plc Nigeria Tedros Adhanom Minister of Health of Ethiopia Ghebreyesus Tedros Adhanom Minister of Health of Ethiopia Ghebreyesus Olusegun Aganga Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment of Nigeria Alfredo Agapiti President Tecnoservice Srl Italy Pranay Agarwal Principal Adviser, Corporate Finance MSP Steel & Power Ltd India and Strategy Vishal Agarwal Head, sub-Saharan Africa Deals and PwC Kenya Project Finance Pascal K. Agboyibor Managing Partner Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe France Manish Agrawal Director MSP Steel & Power Ltd India Deborah Ahenkorah Co-Founder and Executive Director The Golden Baobab Prize Ghana Halima Ahmed Political Activist and Candidate for The Youth Rehabilitation Somalia Member of Parliament Center Sofian Ahmed Minister of Finance and Economic Development of Ethiopia Dotun Ajayi Special Representative to the United African Business Roundtable Nigeria Nations and Regional Manager, West Africa Abi Ajayi Vice-President, Sub-Saharan Africa Bank of America Merrill Lynch United Kingdom Coverage and Origination Clare Akamanzi Chief Operating Officer Rwanda Development Board Rwanda (RDB) Satohiro Akimoto General Manager, Global Intelligence, Mitsubishi Corporation Japan Global Strategy and Business Development Adetokunbo Ayodele Head, Investor Relations Oando Plc Nigeria Akindele Kemi Lala Akindoju Facilitator Lufodo Academy of Nigeria Performing Arts (LAPA) World Economic Forum on Africa 1/23 Olanrewaju Akinola Editor This is Africa, Financial Times United Kingdom Vikram K. -

The World Bank for OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 59793-MW PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 18.1 MILLION Public Disclosure Authorized (US$28.2 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE THE REPUBLIC OF MALAWI FOR THE FINANCIAL SECTOR TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROJECT (FSTAP) Public Disclosure Authorized February 28, 2011 Finance and Private Sector Development East and Southern Africa Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 31, 2011) Currency Unit = Malawi Kawacha (MK) US$1 = MK 150.77 US$1 = SDR 0.640229 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ACH Automated Clearing House AfDB African Development Bank AFRITAC African Technical Assistance Center ATS Automated Transfer System BAM Bankers’ Association of Malawi BESTAP Business Environment Strengthening Technical Assistance Project BSD Banking Supervision Department CAS Country Assistance Strategy CEM Country Economic Memorandum CSC Credit and Savings Co-operatives CSD Central Securities Depository DEMAT Development of Malawi Trader’s Trust DFID UK Department of International Development EFT Electronic Funds Transfer FIMA The Financial Inclusion in Malawi FIRST Financial Sector Reform and Strengthening Initiative FMP Financial Management Plan FSAP Financial Sector -

List of Certain Foreign Institutions Classified As Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms

NOT FOR PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY JANUARY 2001 Revised Aug. 2002, May 2004, May 2005, May/July 2006, June 2007 List of Certain Foreign Institutions classified as Official for Purposes of Reporting on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms The attached list of foreign institutions, which conform to the definition of foreign official institutions on the Treasury International Capital (TIC) Forms, supersedes all previous lists. The definition of foreign official institutions is: "FOREIGN OFFICIAL INSTITUTIONS (FOI) include the following: 1. Treasuries, including ministries of finance, or corresponding departments of national governments; central banks, including all departments thereof; stabilization funds, including official exchange control offices or other government exchange authorities; and diplomatic and consular establishments and other departments and agencies of national governments. 2. International and regional organizations. 3. Banks, corporations, or other agencies (including development banks and other institutions that are majority-owned by central governments) that are fiscal agents of national governments and perform activities similar to those of a treasury, central bank, stabilization fund, or exchange control authority." Although the attached list includes the major foreign official institutions which have come to the attention of the Federal Reserve Banks and the Department of the Treasury, it does not purport to be exhaustive. Whenever a question arises whether or not an institution should, in accordance with the instructions on the TIC forms, be classified as official, the Federal Reserve Bank with which you file reports should be consulted. It should be noted that the list does not in every case include all alternative names applying to the same institution. -

Malawi Rapid Etrade Readiness Assessment

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Malawi Rapid eTrade Readiness Assessment Geneva, 2019 II Malawi Rapid eTrade Readiness Assessment © 2019, United Nations This work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations, its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Photocopies and reproductions of excerpts are allowed with proper credits. This publication has been edited externally. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/DTL/STICT/2019/14 eISBN: 978-92-1-004695-4 NOTE III NOTE Within the UNCTAD Division on Technology and Logistics, the ICT Policy Section carries out policy-oriented analytical work on the development implications of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and e-commerce. It is responsible for the preparation of the Information Economy Report (IER) as well as thematic studies on ICT for Development. The ICT Policy Section promotes international dialogue on issues related to ICTs for development and contributes to building developing countries’ capacities to measure the information economy and to design and implement relevant policies and legal frameworks. -

Malawi Stock Exchange Old Reserve Bank Building, Victoria Avenue, P/Bag 270, Blantyre, Malawi, Central Africa Phone (+265) 01 824 233, Fax

Malawi Stock Exchange Old Reserve Bank Building, Victoria Avenue, P/Bag 270, Blantyre, Malawi, Central Africa Phone (+265) 01 824 233, Fax. (+265) 01 823 636, E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.mse.co.mw Listed Share Information th 11 December, 2015 Weekly Last This P/E P/BV Market After No. Of Range Week’s week’s Dividend Earnings Capitalisation Tax Shares in issue VWAP VWAP MKmn Profit MKmn High (t) Low MSE Buy (t) Sell (t) Price(t) Price (t) Volume Net Yield Yield Ratio Ratio (t) Code (t) (%) (%) Domestic - - BHL CA 960 - 960 - - 60.00 6.25 12.95 7.72 0.35 1,240.25 160.653 129,192,416 - - FMB 1300 1400 1400 - - 100.00 7.14 15.89 6.29 1.53 32,707.50 5,197.00 2,336,250,000 23000 23000 ILLOVO - 23000 24500 23000 435 750.00 3.26 8.25 12.13 3.92 164,092.21 13,531.000 713,444,391 850 820 MPICO CA - 820 900 820 234,373 4.00 0.49 23.34 4.28 0.52 9,421.99 2,199.146 1,149,023,730 25800 25800 NBM CA - 25800 25800 25800 1,946 1535.00 5.95 12.06 8.29 2.73 120,468.39 14,529.000 466,931,738 - - NBS - 2300 2550 - - 55.00 2.16 14.51 6.89 1.58 18,554.91 2,692.518 727,643,339 2800 2800 NICO - 2800 2800 2800 1,743 85.00 3.04 25.12 3.98 0.99 29,205.15 7,335.000 1,043,041,096 - - NITL - 5500 5500 - - 165.00 3.00 29.73 3.36 1.00 7,425.00 2,207.710 135,000,000 - - PCL - 53500 53500 - - 1250.00 2.34 34.40 2.91 0.86 64,336.86 22,134.00 120,255,820 - - REAL 170 200 200 - - 0.00 0.00 22.16 4.51 0.82 500.00 110.808 250,000,000 - - Standard - 44000 44000 - - 1281.00 2.91 11.90 8.40 2.78 103,253.99 12,289.00 234,668,162 - - SUNBIRD - 2300 2209 - - 22.00 1.00 12.03 -

Tax Relief Country: Italy Security: Intesa Sanpaolo S.P.A

Important Notice The Depository Trust Company B #: 15497-21 Date: August 24, 2021 To: All Participants Category: Tax Relief, Distributions From: International Services Attention: Operations, Reorg & Dividend Managers, Partners & Cashiers Tax Relief Country: Italy Security: Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. CUSIPs: 46115HAU1 Subject: Record Date: 9/2/2021 Payable Date: 9/17/2021 CA Web Instruction Deadline: 9/16/2021 8:00 PM (E.T.) Participants can use DTC’s Corporate Actions Web (CA Web) service to certify all or a portion of their position entitled to the applicable withholding tax rate. Participants are urged to consult TaxInfo before certifying their instructions over CA Web. Important: Prior to certifying tax withholding instructions, participants are urged to read, understand and comply with the information in the Legal Conditions category found on TaxInfo over the CA Web. ***Please read this Important Notice fully to ensure that the self-certification document is sent to the agent by the indicated deadline*** Questions regarding this Important Notice may be directed to Acupay at +1 212-422-1222. Important Legal Information: The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”) does not represent or warrant the accuracy, adequacy, timeliness, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the information contained in this communication, which is based in part on information obtained from third parties and not independently verified by DTC and which is provided as is. The information contained in this communication is not intended to be a substitute for obtaining tax advice from an appropriate professional advisor. In providing this communication, DTC shall not be liable for (1) any loss resulting directly or indirectly from mistakes, errors, omissions, interruptions, delays or defects in such communication, unless caused directly by gross negligence or willful misconduct on the part of DTC, and (2) any special, consequential, exemplary, incidental or punitive damages. -

02399-9781451890549.Pdf

WP/02/6 IMF Working Paper Financial Reforms and Interest Rate Spreads in the Commercial Banking System in Malawi Montfort Mlachila and Ephraim W. Chirwa INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND © 2002 International Monetary Fund WP/02/6 IMF Working Paper Policy Development and Review Department Financial Reforms and Interest Rate Spreads in the Commercial Banking System in Malawi Prepared by Montfort Mlachila and Ephraim W. Chirwa1 Authorized for distribution by Doris C. Ross 1anuary 2002 Abstract The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. This study investigates the impact of financial sector reforms on interest rate spreads in the commercial banking system in Malawi. The financial reform program commenced in 1989 when both the Reserve Bank Act and the Banking Act were revised with the easing of entry requirements into the banking system, and indirect monetary policy instruments were subsequently introduced in 1990. The adoption of a floating exchange rate in 1994 marked the end of major policy reforms in the Malawian financial sector. Using alternative definitions of spreads, our analysis shows that spreads increased significantly following liberalization, and panel regression results suggest that the observed high spreads can be attributed to high monopoly power, high reserve requirements, high central bank discount rate and high inflation. JEL Classification Numbers:E43; G21; L13 Keywords: Commercial banks; interest spreads; financial liberalization; Malawi Author's E-Mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] 1 Ephraim Chirwa is at the Department of Economics, Chancellor College, University of Malawi. -

World Bank Document

CONFORMED COPY Public Disclosure Authorized CREDIT NUMBER 2221 MAI (Financial Sector and Enterprise Development Project) between Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF MALAWI and INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Dated June 24, 1991 CREDIT NUMBER 2221 MAI Public Disclosure Authorized DEVELOPMENT CREDIT AGREEMENT AGREEMENT, dated June 24,1991, between REPUBLIC OF MALAWI (the Borrower) and INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION (the Association). WHEREAS: (A) the Borrower, having satisfied itself as to the feasibility and priority of the Project described in Schedule 2 to this Agreement, has requested the Association to assist in the financing of the Project; (B) part of the Project will be carried out by Reserve Bank of Malawi (RBM) with the Borrower’s assistance and, as part of such assistance, the Borrower will make available to RBM part of the proceeds of the Credit as provided in this Agreement; and WHEREAS the Association has agreed, on the basis, inter alia, of the foregoing, to extend the Credit to the Borrower upon the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement and in the Project Agreement of even date herewith between the Association and RBM; Public Disclosure Authorized NOW THEREFORE the parties hereto hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I General Conditions; Definitions Section 1.01. The "General Conditions Applicable to Development Credit Agreements" of the Association, dated January 1, 1985, with the modifications set forth in Schedule 6 to this Agreement (the General Conditions) constitute an integral part of this -

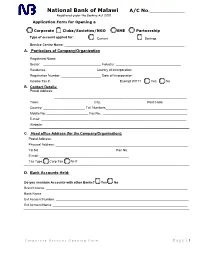

National Bank of Malawi A/C No.______Registered Under the Banking Act 2010 Application Form for Opening A

National Bank of Malawi A/C No.____________ Registered under the Banking Act 2010 Application Form for Opening a Corporate Clubs/Societies/NGO SME Partnership Type of account applied for: Current Savings Service Centre Name: __________________________________________________________________ A. Particulars of Company/Organization Registered Name: _____________________________________________________________________ Sector: ________________________________ Industry: ____________________________________ Residence: ___________________________ Country of Incorporation ____________________________ Registration Number: ______________________ Date of Incorporation Income Tax #: ______________________________________Exempt WHT? Yes No B. Contact Details: Postal Address: _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ Town: ______________________________City: _________________________Post Code: ____________ Country: _______________________ Tel. Numbers_____________________________________________ Mobile No: _______________________ Fax No. : ______________________________________________ E-mail: ________________________________________________________________________________ Website: _______________________________________________________________________________ C. Head office Address (for the Company/Organisation): Postal Address: __________________________________________________________________________ Physical Address: _________________________________________________________________________ -

OECD International Network on Financial Education

OECD International Network on Financial Education Membership lists as at May 2020 Full members ........................................................................................................................ 1 Regular members ................................................................................................................. 3 Associate (full) member ....................................................................................................... 6 Associate (regular) members ............................................................................................... 6 Affiliate members ................................................................................................................. 6 More information about the OECD/INFE is available online at: www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education.htm │ 1 Full members Angola Capital Market Commission Armenia Office of the Financial System Mediator Central Bank Australia Australian Securities and Investments Commission Austria Central Bank of Austria (OeNB) Bangladesh Microcredit Regulatory Authority, Ministry of Finance Belgium Financial Services and Markets Authority Brazil Central Bank of Brazil Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) Brunei Darussalam Autoriti Monetari Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Ministry of Finance Canada Financial Consumer Agency of Canada Chile Comisión para el Mercado Financiero China (People’s Republic of) China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission Czech Republic Ministry of Finance Estonia Ministry of Finance Finland Bank -

English Common Law Tradition

Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes (ROSC) Corporate Governance Public Disclosure Authorized Corporate Governance Public Disclosure Authorized Country Assessment Malawi June 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Overview of the Corporate Governance ROSC Program WHAT IS CORPORATE GOVERNANCE? THE CORPORATE GOVERNANCE ROSC ASSESSMENTS Corporate governance refers to the structures and processes for the direction and control of com - Corporate governance has been adopted as one panies. Corporate governance concerns the relation - of twelve core best-practice standards by the inter - ships among the management, Board of Directors, national financial community. The World Bank is the controlling shareholders, minority shareholders and assessor for the application of the OECD Principles of other stakeholders. Good corporate governance con - Corporate Governance. Its assessments are part of tributes to sustainable economic development by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund enhancing the performance of companies and (IMF) program on Reports on the Observance of increasing their access to outside capital. Standards and Codes (ROSC). The OECD Principles of Corporate Governance The goal of the ROSC initiative is to identify provide the framework for the work of the World weaknesses that may contribute to a country’s eco - Bank Group in this area, identifying the key practical nomic and financial vulnerability. Each Corporate issues: the rights and equitable treatment of share - Governance ROSC assessment reviews the legal and holders and other financial stakeholders, the role of regulatory framework, as well as practices and com - non-financial stakeholders, disclosure and trans - pliance of listed firms, and assesses the framework parency, and the responsibilities of the Board of relative to an internationally accepted benchmark.