COLONIALISM, URBANISATION and the GROWTH of ONITSHA, 1857-1960 *Mmesoma N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parasitology August 24-26, 2015 Philadelphia, USA

Ngele K K et al., J Bacteriol Parasitol 2015, 6:4 http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-9597.S1.013 International Conference on Parasitology August 24-26, 2015 Philadelphia, USA Co-infections of urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis infections among primary school pupils of selected schools in Awgu L.G.A., Enugu State, Nigeria Ngele K K1 and Okoye N T2 1Federal University Ndufu Alike, Nigeria 2Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic, Nigeria study on the co-infections of both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis was carried out among selected primary schools A which include; Central Primary School Agbaogugu, Akegbi Primary School, Ogbaku Primary School, Ihe Primary School and Owelli-Court Primary School in Awgu Local Government Area, Enugu State Nigeria between November 2012 to October 2013. Sedimentation method was used in analyzing the urine samples and combi-9 test strips were used in testing for haematuria, the stool samples were parasitologically analyzed using the formal ether technique. A total of six hundred and twenty samples were collected from the pupils which include 310 urine samples and 310 stool samples. Out of the 310 urine samples examined, 139 (44.84%) were infected with urinary schistosomiasis, while out of 310 stool samples examined, 119 (38.39%) were infected with intestinal schistosomiasis. By carrying out the statistical analysis, it was found that urinary schistosomiasis is significantly higher at (p<0.05) than intestinal schistosomiasis. Children between 12-14 years were the most infected with both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis with prevalence of 45 (14.84%) and 48 (15.48%), respectively, while children between 3-5 years were the least infected with both urinary and intestinal schistosomiasis 30 (9.68%) and 25 (8.06%), respectively. -

Growth of the Catholic Church in the Onitsha Province Op Eastern Nigeria 1905-1983 V 14

THE CONTRIBUTION OP THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OP EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 V 14 - I BY REV. FATHER VINCENT NWOSU : ! I i A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY , DEGREE (EXTERNAL), UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1988 ProQuest Number: 11015885 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015885 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 s THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAITY TO THE GROWTH OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE ONITSHA PROVINCE OF EASTERN NIGERIA 1905-1983 By Rev. Father Vincent NWOSU ABSTRACT Recent studies in African church historiography have increasingly shown that the generally acknowledged successful planting of Christian Churches in parts of Africa, especially the East and West, from the nineteenth century was not entirely the work of foreign missionaries alone. Africans themselves participated actively in p la n tin g , sustaining and propagating the faith. These Africans can clearly be grouped into two: first, those who were ordained ministers of the church, and secondly, the lay members. -

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

Geoelectrical Sounding for the Determination of Groundwater Prospects in Awgu and Its Environs, Enugu State, Southeastern Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 5, Issue 1 Ver. I (Jan. - Feb. 2017), PP 14-22 www.iosrjournals.org Geoelectrical Sounding for The Determination Of Groundwater Prospects In Awgu And Its Environs, Enugu State, Southeastern Nigeria OKEKE J. P.1; EZEH C. C2. ; OKONKWO A. C3. 1,2,3(Department of Geology and Mining, Enugu state University of science and Technology, Enugu State, Nigeria. West Africa). [email protected] Abstract: Geoelectrical sounding to determine the groundwater prospect in Awgu and its environs has been carried out. The study area lies within longitudes 007025’E and 0070 35’E and latitudes 06002’N and 06017’N with an area extent of 513sqkm. The area is underlain by two lithostratigraphic units, Awgu Shale and Owelli Sandstone. A total of ninety five (95) Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES) was acquired employing the Schlumberger electrode array configuration, with a maximum electrode separation ranging from 700m to 800m. Data analysis was done using a computer program RESOUND to generate the layer apparent resistivity, thickness and depth. A maximum of eight (8) layer resistivity were generated in each sounding point with a depth range of 50m to 356m. From the interpreted VES data layer 6, 7, and 8 are possible target for prospective aquifer horizons. Interpreted geoelectric layers show a sequence of shale/sand – shale sand – sand. Various contour maps were constructed using surfer 10 contouring program- Iso resistivity, Isochore (depth), Isopach (thickness), Longitudinal conductance and transverse resistance to show variation of parameters in the study area. -

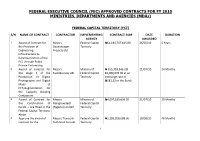

FEC Approved Contracts 2010

FEDERAL EXECUTIVE COUNCIL (FEC) APPROVED CONTRACTS FOR FY 2010 MINISTRIES, DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES (MDAs) FEDERAL CAPITAL TERRITORY (FCT) S/N NAME OF CONTRACT CONTRACTOR IMPLEMENTING CONTRACT SUM DATE DURATION AGENCY AWARDED 1 Award of Contract for Messrs. Federal Capital N61,194,747,645.00 26/05/10 5 Years the Provision of Deanshanger Territory Engineering Projects Ltd. Infrastructure to Katampe District of the FCC through Public Private Partnership 2 Award of contract for Messrs. Ministry of N 355,393,546.20( 21/07/10 24 Months the stage II of the Swedesurvey AB Federal Capital €1,960,035.00 at an Production of Digital Territory exchange rate of Photography and Digital N181.32 to the Euro) Maps of FCT/Augmentation for the Capacity Building Component 3 Award of Contract for Messrs. Ministry of N4,097,185,656.30 21/07/10 20 Months the Construction of Mangrovetech Federal Capital Karshi – Ara Road in the (Nigeria) Limited Territory Federal Capital Territory, Abuja 4 Approve the award of Messrs Transurb Federal Capital N1,289,958,088.00 18/08/10 48 Months contract for the Technirail Consult Territory 1 provision of Project Limited Management Services for Abuja Rail Mass Transit Project (Lots 1 & 3) 5 Award of Contract for Messrs. SCC Ministry of N733,316,641.47 01/09/10 12 Months the Operation, (Nigeria) Limited Federal Capital Maintenance and Territory Training of Staff for Wupa Basin Sewage Treatment Plant 6 Award of Contract for Messrs. Pentagon Ministry of N927,600,000.00 22/09/10 12 Weeks the Supply of 60,000 Group of Federal Capital Units of 240 Litres Plastic Companies Ltd Territory British Waste Bins 7a Award of Contract for Messrs. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

Economics of Pineapple Production in Awgu Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria

©2020 Scienceweb Publishing Journal of Agricultural and Crop Research Vol. 8(11), pp. 245-252, November 2020 doi: 10.33495/jacr_v8i11.20.133 ISSN: 2384-731X Research Paper Economics of pineapple production in Awgu Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria David Okechukwu Enibe* • Chinecherem Joan Raphael Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam, Anambra State, Nigeria. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: +2348137829887. Accepted 21th June, 2020. Abstract. The study analyzed the economics of pineapple production in Awgu Local Government Area (LGA) of Enugu State, Nigeria. Data for the study were collected from 50 respondents from Amoli and Ihe communities of the LGA through a simple random sampling technique. The communities were purposively selected because they contain higher concentration of pineapple farmers. Primary data were collected using interview schedule administered to the respondents. Data were realized with descriptive statistics, enterprise budgeting techniques and multiple regression analysis. The study revealed that (36%) of the farmers had farming experience of 1 to 10 years’ experience in pineapple production, indicating that new farmers entered the crop’s production sector within the last decade. The enterprise proved profitable with farmers’ net return on investment value of 1.7. Farm size, cost of input, level of education and household size significantly determined net farm income. It was further revealed that poor access road and high transportation cost were the main constraints of the pineapple producers. The study concluded that profitable production opportunities exist on the crop. The study recommends that extension agencies should encourage more new farmers to exploit pineapple production potentials while encouraging its existing farmers to scale up production through farm size increment, reinvestment of their gains and production knowledge increase. -

Paleoenvironments of the Gulf of Guinea

_________________________________________O_ C__EA _ N_O_L_O_G_'_C_A_A_C_T_A_, _1 _98_'_, _N_O_S_P_ ~e------- P.. Jc:ocnvi ronmenl Gulf of Guinea Paleoenvironments For:.mÎniferli Transl:fcssions·regn:ssions Black Sh.. le s PaJéoenvironnemenl of the Gulf of Guinea Golfe de Guinée For:t minifèrcs Transgressions- régressions Mnmes noire s S. W. Pellefs Dcpartmenl of Geology. University of Ibadan, Ibadan. Nigeria. ABSTRACT Foraminireral asse mblages in Ihrec margi nal basins in the Gulf of Guinea (name] y, the Benue Trough, the Dahomey Embaymenl , the Niger Della) show maximum development during the major marine transgressions whic h transpi rcd in the Middle 10 Laie Albian, Late Cenomanhtn 10 Early Turonian, LaIe Turonian 10 Early Sanlonian, Late Campanian 10 Maastrichtian, Middle to LaIe Paleocene, M.iddle 10 Laie Eocene, Middle Üligocene, and Early to Middle Miocene . The Oligoccnc and younger transgressions are more pronounced in the Niger Delta where f os s ilif e r o u ~ marine shales are interealated wi thin delt'lie sands. Major transgressio ns in the Gul f of Gui nea eoincided with global LaIe Cretaeeous to Tertiary sca level rises. The transgressive shall ow shelf benthonie foraminiferal assemblages in the exposed pariS of the Benue T rough and Ihe Dahomey Embayme nt show a progressive increase in faunal diversity from the Albian to the Eocene. This was due 10 im prove marine conditions in these margi nal basins when oceanic circulation was established in the Gulf of Guinea. The weil known Mid-Cretaceous oxygen tleficiencies in the world 's oceans and epicontinental seas were feh in the Benue Trough where anaerobic shales and oxygen.starved bent honic fomminiferal assemblages occur in Upper Cenomanian-Lower Turonian and in Upper Turonian-Lowcr Sanlo nian black shalcs. -

Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment

Hostalia ConsultaireE2924 NigerianNigerian Erosion Erosion and Watershed Managementand Watershed Project Management Health and EnvironmentProject NEWMAP Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Public Disclosure Authorized Framework (ESMF) FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Hostalia Consultaire Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project NEWMAP FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 2011 Prepared by Dr. O. A. Anyadiegwu Dr. V. C. Nwachukwu Engr. O. O. Agbelusi Miss C.I . Ikeaka 2 Hostalia Consultaire Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment Table of Content Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................15 Background ..........................................................................................................................15 TRANSLATION IN IBO LANGUAGE..........................................................22 TRANSLATION IN EDO LANGUAGE.........................................................28 TRANSLATION IN EFIK...............................................................................35 CHAPTER ONE..............................................................................................43 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND TO NEWMAP.............................43 1.0 Background to the NEWMAP...................................................................................43 -

S/No Name of Mfb Address State Status Capital Requirement

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 CURRENT S/NO NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE STATUS CAPITAL REQUIREMENT GEO Local Gov Area 1 AACB MFB NNEWI / AGULU ROAD, ADAZI ANI , ANAMBRA STATE SE Anaocha ANAMBRA STATE 1 Billion 2 AB MFB 9, OBA AKRAN ROAD, IKEJA, LAGOS SW Ikeja LAGOS NATIONAL 5 Billion 3 ABC MFB MISSION ROAD, OKADA, ORIN NORTH-EAST LGA, EDO STATE SS Ovia North-East EDO TIER 2 UNIT 50 Million 4 ABESTONE MFB COMMERCE HOUSE, BESIDE GOVERNMENT HOUSE, IGBEIN HILLS, ABEOKUTA, LAGOS STATE SW ABEOKUTA OGUN TIER 1 UNIT 200 Million 5 ABIA STATE UNIVERSITY MFB UTURU, ISUIKWUATO LGA, ABIA STATE SE Isuikwuato ABIA STATE 1 Billion 6 ABIGI MFB 28, MOBORODE ODOFIN ST., ABIGI IJEBU WATERSIDE, OGUN STATE SW Ogun Waterside OGUN TIER 2 UNIT 50 Million 7 ABOVE ONLY MFB BENSON IDAHOSA UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, UGBOR,BENIN CITY, BENIN, EDO STATE SS Oredo EDO TIER 1 UNIT 200 Million NE Bauchi 8 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY (ATBU) MFB ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, YELWA CAMPUS, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE BAUCHI TIER 1 UNIT 200 Million PLOT 251, MILLENIUM BUILDERS PLAZA, HERBERT MACAULAY WAY, CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT, NC Municipal Area Council 9 ABUCOOP MFB GARKI, ABUJA FCT STATE 1 Billion 10 ABULESORO MFB LTD E7, ADISA STREET, ISAN EKITI EKITI TIER 2 UNIT 50 Million 11 ACCION MFB ELIZADE PLAZA, 4TH FLOOR, 322A IKORODU ROAD, ANTHONY, IKEJA, LAGOS SW Eti-Osa LAGOS NATIONAL 5 Billion 12 ACE MFB 3 DANIEL ALIYU STREET, KWALI, F.C.T., ABUJA NC Kwali FCT TIER 2 UNIT 50 Million 13 ACHINA MFB OYE MARKET SQUARE ACHINA AGUATA L.G.A ANAMBRA. -

South East Capital Budget Pull

2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii 2014 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Compiled by Centre for Social Justice For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) iii First Published in October 2014 By Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja. Website: www.csj-ng.org ; E-mail: [email protected] ; Facebook: CSJNigeria; Twitter:@censoj; YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/CSJNigeria. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgement v Foreword vi Abia 1 Imo 17 Anambra 30 Enugu 45 Ebonyi 30 v Acknowledgement Citizens Wealth Platform acknowledges the financial and secretariat support of Centre for Social Justice towards the publication of this Capital Budget Pull-Out vi PREFACE This is the third year of compiling Capital Budget Pull-Outs for the six geo-political zones by Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP). The idea is to provide information to all classes of Nigerians about capital projects in the federal budget which have been appropriated for their zone, state, local government and community. There have been several complaints by citizens about the large bulk of government budgets which makes them unattractive and not reader friendly. -

Biostratigraphy of a Section Along Port Harcourt to Enugu Express Way, Exposed at Agbogugu, Anambra Basin, Nigeria

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2012, 3 (1):384-392 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Biostratigraphy of a Section along Port Harcourt to Enugu Express Way, Exposed at Agbogugu, Anambra Basin, Nigeria *Omoboriowo, A. O. 1, Soronnadi-Ononiwu,C. G2, Awodogan, O. L. 1 1Department of Geology, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2 Department of Geology, Niger Delta University, Amassoma, Bayelsa, Nigeria _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The biostratigraphy of stratigraphic sections exposed at Agbogugu along the Port Harcourt – Enugu Expressway was studied and some key evaluations were reached. The stratigraphic section (The Enugu Shale) is one of the Campanian – Maastrichtian successions of the Anambra Basin, Southeastern Nigeria. It is located at latitude 60151N and longitude 7 021 1E of Greenwich Meridian. The lithologic units of the succession are basically shales with ironstone intercalation showing a likely marine depositional environment. The method of study involved the collection of sample to evaluate the final subsequent laboratory analysis of collected sample to evaluate final observable features. A total of nine (9) samples were collected from this outcrop. From the laboratory analysis carried out, a lithological description of all samples collected depth by depth was made with 2.0m HCI to check the presence or absence of calcareous forms. A sand/shale ratio plot was made from the wet sieve analysis and an approximate percent of sand and shale were interpreted. The result shows more shales than sand in the sediment showing a marine origin of deposition. Also from micropaleontological analysis made, 6 diverse forms of benthic arenaceous foraminifera assemblages were recovered.