Improving Organisational Effectiveness of Coalition Headquarters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulgaria in EU's Mirror SINCE 1990

z z z z EVENTS ANALYSES INTERVIEWS Issue 2(173) CO%86,1(66 NNECT March-April 2017 $ආൾඋංർൺඇ&ඁൺආൻൾඋඈൿ&ඈආආൾඋർൾංඇ%ඎඅൺඋංൺ Bulgaria in EU's Mirror SINCE 1990 WITH ACCESS TO 100 COUNTRIES 21 000 LAWYERS 160 LAW FIRMS AT HOME WORLDWIDE COMMERCIAL & COMPANY LAW COMPETITION & ANTITRUST MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS ENERGY & RENEWABLES ADMINISTRATIVE LAW LITIGATION & ARBITRATION & PUBLIC PROCUREMENT BANKING & FINANCING LAW TAXATION & LABOR TRADEMARKS, PATENTS IT, MEDIA & TELECOMMUNICATIONS & LICENSING Legal: 500: Chambers Europe: Chambers Global: IFLR 1000: “Excellent, comprehensive “More western than others” “Innovative and practical, “They are the best and responsive services” “One of the best in Bulgaria” entirely client & business when it comes to advising investors, “Excellent – prompt, oriented” they know how the law works…” efficient and extremely knowledgeable of the local environment” e-mail: [email protected] ∙ www.penkov-markov.eu ∙ telephone: (+359 2) 971 3935 executive's remarks 1 Bulgaria needs more EU A stable government and more European integration are a must if we want to have predictable political environment in Bulgaria. “No more business as usual” sounded as the main message of the Transatlantic week in Brussels where 37 representatives from 23 AmChams exchanged views on advocacy and ways to cooperate. The 25th anniversary of the EU Single Market and Bulgaria’s 10 years of EU membership provided the chance to draw up a balance sheet. GDP has increased by nearly 70% in nominal terms during that period and, according to Euro barometer, Bulgarians are happier now than before. Some 70% of Bulgarian exports are destined for the EU; a similar percentage goes to the countries at the “fastest” EU speed – Germany, France, Italy and the Benelux. -

The North American Forest Sector Outlook Study 2006-2030

Projections for the United States and Canada to 2030 have been made with a global model to account for concurrent changes in other countries. Three The North American Forest future scenarios were investigated: two IPCC-based scenarios assuming the rapid growth of wood-based energy, and one IPCC-based scenario without this assumption. The model, under the IPCC scenarios, accounted for trends Sector Outlook Study in population, income and land use along with emerging technology and predicted changes to consumption patterns for wood products and bioenergy. Markets for wood products, which mainly are destined for the construction 2006-2030 sector in North America, are projected to recover by 2015 under all three scenarios examined. Projections suggest that, in spite of declining use of paper for media, other paper and paperboard for packaging and miscellaneous uses will continue to enjoy strong global demand. United Nations publication Sales No E.11.II.E.4 ISSN 1020-2269 USD 22 http://www.unece.org/forests/outlook/welcome.html ISBN 978-92-1-117057-3 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Designed and printed by the Publishing Service, United Nations, Geneva — GE.12-20601 — March 2012 — 1,671 — ECE/TIM/SP/29 Economic Commission for Europe of the United Nations GENEVA TIMBER AND FOREST STUDY PAPER 29 The North American Forest Sector Outlook Study 2006-2030 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Economic Commission for Europe of the United Nations Note The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Summaries of Published Works

ACCIDENTS AND DISASTERS. Chronicle of Communist Industrialization. Summary The monograph deals with a completely unexplored topic in Bulgarian historiography – the problem of industrial accidents and disasters during the communist rule in the country. The study is based on a rich and varied archival material, mainly documents from the funds of the Politburo and the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, the Central Council of the Bulgarian Trade Unions, the Committee for Disclosing the Documents and Announcing Affiliation of Bulgarian Citizens to the State Security and Intelligence Services of the Bulgarian National Army. A significant number of interviews and recollections of people who survived or witnessed severe industrial disasters are also used. Researching the topic allows the author to present the general picture of working conditions in Bulgaria during the entire period of communist rule, organization of production, economic and social policy of the state. At the same time, he considers and analyzes various examples of accidents in more detail, as well as some catastrophes that have become emblematic for this period. Based on the specific cases, he makes conclusions about the state of the industry, about the social and labor relations, about the mechanisms through which decisions were made and the planned measures were implemented. In addition, all these events are placed in the broad context of the economic and political situation in the country in each period of its development. The text follows the historical-chronological approach, which also determines the structure of the book. It gives the opportunity to see in full the problem, as well as the social causes and phenomena that gave rise to it. -

BG PAVILION at PQ2019 AUTORS an ENEMY of the PEOPLE Ralitza Toneva

BG PAVILION AT PQ2019 AUTORS AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Ralitza Toneva By Henrik Ibsen Filipov, Evgeni Doichinov, Ralitza Toneva is a stage and costume designer since 2007. She works DRAMA for theatre, dance productions, and films. Ralitza is also designing sets, THEATRE Krasimira Kuzmanova, Sergei Translation: Maria Nikolova Konstantinov, Veselin Plachkov costumes, and light. Her latest works are exclusively based on light Director: Kris Sharkov design. Some of the performances she’s done lately are: “Neon” Scenography: Ralitsa Toneva Drama and Puppet Theatre by Garage collective, ”The Boy From The Last Row” dir. Photographer: Georgi Enchev “Ivan Radoev”, Kris Sharkov, “Perfectly pink” by Iva Sveshtarova. Pleven Since 2011, she and Spartak Yordanov have collabo- Cast: Vasil Chitanov, rated to develop a specific visual technique, similar Kamelia Hatib, Adrian www.theatre-pleven.bg to painting under the camera. They also experiment with video and live performance, interacting with mu- sicians and poets in the projects “MacroStation” 6 7 ANTIGONE By Jean Anouilh Assistant director: Cast: Daria Simeonova, Katalin Sofia Theatre, DRAMA Hristo Mitskov Stareyshinska, Bozhidar Yordanov, Sofia THEATRE Translation: Hristo Mitskov Set design: Stanislav Pamukchiev Iriney Konstantinov, Yordanka Stage editing and staging: Costumes: Petya Boyukova Lyubenova, Nikolay Varbanov, Rosen www.sofiatheatre.eu Ivan Dobchev Music: Hristo Namliev Belov, Nikolay Dimitrov, Ivan Krumov Director: Ivan Dobchev Photographer: Simon Varsano 8 9 AUTORS Stanislav Pamukchiev Petya Boyukova Stanislav Pamukchiev graduated in Mural Painting from the National Petya Boyukova works as a stage and costume designer for theatrical DRAMA AUTORS Academy of Art, where he is now a professor. His works have been performances. -

Cultural Heritage

Chapter 17: Cultural Heritage URS-EIA-REP-202375 Table of Contents 17 Cultural Heritage ...................................................................................... 17-1 17.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 17-1 17.2 Scoping ............................................................................................................ 17-2 17.3 Spatial and Temporal Boundaries ........................................................................ 17-4 17.3.1 Terrestrial Cultural Heritage Study and Survey Areas ............................... 17-4 17.3.2 Marine Cultural Heritage Study and Survey Areas ................................... 17-5 17.4 Baseline Data .................................................................................................. 17-21 17.4.1 Methodology and Data ........................................................................ 17-21 17.4.2 Secondary Data .................................................................................. 17-21 17.4.2.1 Desk-based Research .................................................................. 17-21 17.4.2.2 Reporting Methodology ............................................................... 17-23 17.4.2.3 Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................. 17-23 17.4.3 Data Gaps .......................................................................................... 17-25 17.4.4 Primary Data/Baseline Surveys ........................................................... -

Forest Land Ownership Change in Bulgaria

Forest Land Ownership Change in Bulgaria COST Action FP1201 FACESMAP Country Report COST Action FP1201 Forest Land Ownership Change in Europe: Significance for Management and Policy (FACESMAP) Forest Land Ownership Change in Bulgaria COST Action FP1201 FACESMAP Country Report Authors Nickola Stoyanov University of Forestry 10, Kliment Ohridski Blvd. 1756 Sofia Bulgaria Emil Kitchoukov University of Forestry 10, Kliment Ohridski Blvd. 1756 Sofia Bulgaria Maria Stoyanova Forest Research Institute Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS) 132, Kliment Ohridski Blvd. 1756 Sofia Bulgaria Maria Sokolovska Forest Research Institute Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS) 132, Kliment Ohridski Blvd. 1756 Sofia Bulgaria The COST Action FP1201 FACESMAP Country Reports are edited by the European Forest Institute Central-East and South-East European Regional Office (EFICEEC-EFISEE) at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU). The Country Reports are not subject to external peer review. The responsibility for the contents of the Country Reports lies solely with the country author teams. Comments and critique by readers are highly appreciated. The main parts of these Country Reports will be included in the upcoming EFICEEC-EFISEE Research Report “Forest Land Ownership Change in Europe. COST Action FP1201 FACESMAP Country Reports, Joint Volume”, published online on the FACESMAP (http://facesmap.boku.ac.at) and EFICEEC-EFISEE (www.eficeec.efi.int) websites. Reference: Stoyanov, N., Kitchoukov, E., Stoyanova, M., Sokolovska, M. (2015) -

Theoretical Debates in Bulgaria During the Great Depression Confronting Sombart, Marx and Keynes

Theoretical Debates in Bulgaria during the Great Depression Confronting Sombart, Marx and Keynes Nikolay Nenovsky* The main purpose of this article is to understand how Bulgarian economists interpreted the Great Depression, by reviewing the theoretical models they used and the solutions they advocated. In particular, this means: (i) clarifying what made them gradually realise the structural characteristics of the crisis and (ii) identifying the main channels and the main theories underlying the analysis of crises and depressions. The paper comprises six sections. The first section offers a brief survey of the Bulgarian economy and political developments prior to the Depression. Section two presents Bulgarian economic thought on the eve of the Depression according to five intellectual currents. Section three identifies and discusses the two main models of interpretation of the Great Depression—a cyclical and a structural model. The next two sections explain the evolution of economic thinking following the main phases of the crisis (deflation/agrarian crisis and monetary/banking crisis). Section six focuses on Marxist interpretations of the crisis. The last section offers a few concluding observations. Keywords : Great Depression, Balkan economies, Bulgaria, Marxism, agrarianism, crises, Keynes Débats théoriques en Bulgarie durant la Grande Dépression. Une confrontation entre Sombart, Marx et Keynes L’objet principal de cet article est de comprendre comment les économistes bulgares ont interprété la Grande Dépression, c’est-à-dire, de mettre en évidence les modèles théoriques qu’ils ont utilisé et les solutions qu’ils ont ∗ University of World and National Economy (Department of Finance), Sofia; University of Orléans (Le STUDIUM) and ICER. -

INNOVATION.BG 2016 Innovation.Bg Innovation Powered by Talent EDITORS

INNOVATION.BG 2016 InnovationWWW.ARCFUND.NET BG AR Funded by the Innovation.bg Innovation Powered by Talent EDITORS Prof. Teodora Georgieva, PhD, Senior Fellow, Applied Research and Communications Fund Mr. Ruslan Stefanov, Coordinator, Innovation.bg Group, Applied Research and Communications Fund WORKING GROUP INNOVATION.BG PhD Todor Galev, Senior Fellow, Applied Research and Communications Fund Assoc. Prof. Engineer Roumyana Georgieva PhD, Technical University, Gabrovo Prof. Teodora Georgieva, PhD, Senior Fellow, Applied Research and Communications Fund Mr. Radoslav Yordanov, PhD, Academy of Economics, Svishtov Ms. Denitsa Marinova, Project Coordinator, Applied Research and Communications Fund Mr. Boyko Todorov, Senior Fellow, Center for the Study of Democracy Ms. Maya Tsaneva, Fellow, Applied Research and Communications Fund Ms. Daniela Chonkova, Program Coordinator, Applied Research and Communications Fund PhD Todor Yalamov, Coordinator, IT Group, Applied Research and Communications Fund EXPERT COUNCIL ON INNOVATION AT THE APPLIED RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS FUND Prof. Marin Petrov, PhD, Honorary Chairperson, Expert Council on Innovation, Applied Research and Communications Fund Prof. Teodora Georgieva, PhD, Chairperson, Expert Council on Innovation, Applied Research and Communications Fund Prof. Bistra Boeva, PhD, Department of International Economics and Politics, University of National and World Economy Assoc. Prof. Violeta Bozhanova, PhD, Academic Secretary General, Agricultural Academy Ms. Mara Georgieva, Kapital weekly Assoc. Prof. Lilia Damianova, Faculty of Chemical and System Engineering, University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy Prof. Mitko Dimitrov, PhD, Director, Economics Research Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Ms. Vanya Jeleva, Head of R&D, Innovation and Information Society Department, National Statistical Institute Mr. Nikolay Iliev, Manager, Datecs PhD Engineer Ventsislav Slavkov, Cluster Board Chairman, Mechatronics and Automatisation Cluster Assoc. -

Mathematics Without Borders - Spring 2019 Group 3

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2019 GROUP 3 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abareles, En Boyle Miguel O. Philippines Capiz 3 Certificate 2 Abdao, Djiren Riel Loneza Philippines Taguig City 3 Certificate 3 Abduazizova Rayyona Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 4 Abdukahhorova Mohinur Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 5 ABDULAZEEZ AWONUGA Nigeria Abuja 3 Certificate 6 Abdulhaev Abdumalik Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 7 Abdullaeva Mohinur Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Certificate 8 Abdumavlyanova Mubina Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Silver 9 Abdumavlyanova Mubina Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Bronze 10 Abdurahmonova Malika Uzbekistan Tashkent 3 Bronze 11 Adelin Redzhepov Chaushev Bulgaria Kazanlak 3 Certificate 12 Adelina Petrova Sheytanova Bulgaria Plovdiv 3 Certificate 13 Adrian Danailov Petrov Bulgaria Varna 3 Certificate 14 Adrian Petrov Shivachev Bulgaria Burgas 3 Certificate 15 Adriana Georgieva Shukova- 3.B Bulgaria Sofia 3 Certificate 16 Adriana Stamenova Stamova Bulgaria Yambol 3 Certificate 17 Adriyana Grigorieva Karaykova Bulgaria Sofia 3 Certificate 18 Agabayli Elkhan Azerbaijan Baku 3 Certificate 19 Ahmadjanov Abror Uzbekistan Fergana 3 Silver 20 Ahmadzhanov Zhahongir Uzbekistan Namangan 3 Silver 21 Aibike Urbaeva Kyrgyzstan Bishkek 3 Certificate 22 Akhundov Adnan Azerbaijan Baku 3 Gold 23 Aksel Aleksiev Kirilov Bulgaria Razgrad 3 Gold 24 Aksel Salih Kisyoski Bulgaria Kozloduy 3 Certificate 25 Alakbarli Jahandar Azerbaijan Baku 3 Certificate 26 Alakbarova Elif Azerbaijan Baku 3 Certificate 27 Albano, Reese Reilly -

Cadet-Nav 2021

“MIRCEA CEL BATRAN” NAVAL ACADEMY THE 43rd SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE FOR STUDENTS CADET-NAV 2021 PROGRAMME 09th - 10th of April 2021 CONSTANTA Organizing Committee Captain (N) Assoc. Prof. Eng. Alecu TOMA, PhD Captain (N) Assoc. Prof. Dinu ATODIRESEI, PhD Captain (N) Assoc. Prof. Eng. Paul BURLACU, PhD Colonel Assoc. Prof. Catalin POPA, PhD Captain (N) Eng. Cătălin CLINCI, PhD Commander (N) Assoc. Prof. Filip NISTOR, PhD Commander (N) Assoc. Prof. Adrian POPA, PhD LCDR Assoc. Prof. Eng. Alexandru COTORCEA, PhD Commander (N) Assoc. Prof. Florentiu DELIU, PhD Commander Assoc. Prof. Eng. Sergiu LUPU, PhD LCDR Lecturer Daniel MARASESCU, PhD Lieutenant (N) Eng. Ionuţ Cristian SCURTU, PhD Lieutenant (N) Eng. Sergiu ŞERBAN, PhD Lieutenant Lecturer Eng.Ovidiu CRISTEA, PhD Associate Prof. Andrei BAUTU, PhD Lecturer Edith KAITER, Phd 2 CONTENTS 1. Navigation and Transport ………………………… 5 2. Engineering and Management ……………………. 37 3. Military Sciences and Information ……………… 59 4. Electrical Engineering …………………………… 63 5. Weapons and Communications ………………… 80 6. Mechanical Engineering …………………………. 86 7. Fundamental Sciences ...…………………………… 98 8. Foreign Languages ……............................................ 106 3 4 I. SECTION: NAVIGATION AND TRANSPORT Section Committee: Chairman: Lieutenant Lecturer Eng. Sergiu ȘERBAN, PhD Members: Assoc. Prof. Eng. Romeo BOȘNEAGU, PhD Lecturer Marius APETROAEI, PhD Lieutenant Jr. Eng. Andra NEDELCU, PhD junior 1. Maritime transport of freight Authors: stud. Mariana-Mădălina GEORGESCU, stud. Monica-Florentina EFTINCĂ Scientific Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Dan LASCU, PhD Institution: “Mircea cel Batran” Naval Academy, Constanta Abstract This document wishes to highlight the importance, advantages and requirements of maritime transport. It is known that maritime transport has had from its oldest economic, social, strategic, and in some cases, even political, important. -

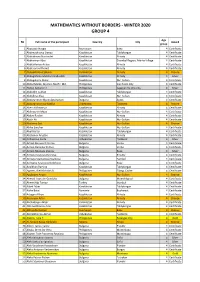

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2020 Group 4

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2020 GROUP 4 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abaszade Nargiz Azerbaijan Baku 4 Certificate 2 Abdimazhitova Dariya Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 4 Certificate 3 Abdrahman Nurdaulet Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 4 Abdraimov Abai Kazakhstan Zhambyl Region, Merke Village 4 Certificate 5 Abdrakhman Aituar Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 6 Abdrasulov Khamit Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 7 Abduakhitova Sabina Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Bronze 8 Abdugafarov Mukhammadsolikh Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Silver 9 Abdugaliyev Alidar Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 4 Certificate 10 Abdul Malek, Alyanna Noof J. Md. Philippines San Pablo City 4 Certificate 11 Abdul, Sehanor A. Philippines Cagayan De Oro City 4 Silver 12 Abduldin Askhat Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 4 Certificate 13 Abdullina Alua Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 4 Certificate 14 Abdurahman Niyazi Aptaraman Bulgaria Aytos 4 Certificate 15 Abdurahmonova Malika Uzbekistan Tashkent 4 Bronze 16 Aben Abilmansur Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 17 Abilmazhin Maya Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 4 Certificate 18 Abilov Ruslan Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 19 Abish Ali Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 4 Certificate 20 Abisheva Sati Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 4 Bronze 21 Ablay Sanzhar Kazakhstan Nur-Sultan 4 Certificate 22 Abyl Nartai Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 4 Certificate 23 Abzhanov Arystan Kazakhstan Almaty 4 Certificate 24 Adhamova Saida Uzbekistan Tashkent 4 Silver 25 Adrian Borisov Dimitrov Bulgaria Varna 4 Certificate 26 Adrian Danailov Petrov Bulgaria Varna 4 Certificate 27 Adrian Nikolaev Vasilev Bulgaria Ruse 4 Silver 28 Adriana Ivanova Gesheva Bulgaria Plovdiv 4 Certificate 29 Adriana Stamenova Stamova Bulgaria Yambol 4 Certificate 30 Adriyana Yasenova Bedzheva Bulgaria Ruse 4 Certificate 31 Adylkhan Ramina Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 4 Certificate 32 Agasen, Riel Nicholas B. -

Innovation.Bg Report 2015

InnovationBG Carbon Economy Energy Efficiency Renewable Energy Sources Transport Green Policies Green Business Practices ARC Fund Funded by the Green Innovation.bg Good practices and policy options EDITORS Prof. Teodora Georgieva, Chairperson, Expert Council on Innovation, Applied Research and Communications Fund Mr. Ruslan Stefanov, Coordinator, Innovation.bg Group, Applied Research and Communications Fund WORKING GROUP GREEN INNOVATION.BG Mr. Ruslan Stefanov, Coordinator, Innovation.bg Group, Applied Research and Communications Fund Ms. Nadejda Gantcheva, Expert, Applied Research and Communications Fund Prof. Teodora Georgieva, Chairperson, Expert Council on Innovation, Applied Research and Communications Fund Dr. Fani Koleva, University of National and World Economy Ms. Denitsa Marinova, Project Coordinator, Applied Research and Communications Fund Dr. Miglena Molhova, University of National and World Economy Mr. Metodi Naydenov, Project Officer, Applied Research and Communications Fund Mr. Iasen Nestorov, Expert, Applied Research and Communications Fund Ms. Daniela Tchonkova, Program Coordinator, Applied Research and Communications Fund EXPERT COUNCIL ON INNOVATION AT THE APPLIED RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS FUND Prof. Teodora Georgieva, Chairperson, Expert Council on Innovation, Applied Research and Communications Fund Prof. Bistra Boeva, Department of International Economics and Politics, University of National and World Economy Ass. Prof. Violeta Bozhanova, Academic Secretary General, Agricultural Academy Ms. Mara Georgieva, Kapital weekly Prof. Lilia Damianova, Faculty of Chemical System Engineering, University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy Prof. Mitko Dimitrov, Director, Economics Research Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Ms. Vanya Jeleva, Head of R&D, Innovation and Information Society Department, National Statistical Institute Ms. Genoveva Zhecheva, Head of Section ”Transnational Science Initiatives·, Science Directorate, Ministry of Education and Science Mr. Nikolay Iliev, Manager, Datecs Ltd.