A Collection of Essays on Place, Skills and Governance in the Yorkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Roman Yorkshire

ROMAN YORKSHIRE: PEOPLE, CULTURE, LANDSCAPE By Patrick Ottaway. Published 2013 by The Blackthorn Press Chapter 1 Introduction to Roman Yorkshire ‘In the abundance and variety of its Roman antiquities, Yorkshire stands second to no other county’ Frank and Harriet Wragg Elgee (1933) The Yorkshire region A Roman army first entered what we now know as Yorkshire in about the year AD 48, according to the Roman author Cornelius Tacitus ( Annals XII, 32). This was some five years after the invasion of Britain itself ordered by the Emperor Claudius. The soldiers’ first task in the region was to assist in the suppression of a rebellion against a Roman ally, Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes, a native people who occupied most of northern England. The Roman army returned to the north in about the years 51-2, once again to support Cartimandua who was, Tacitus tells us, now under attack by her former consort, a man named Venutius ( Annals XII, 40). In 69 a further dispute between Cartimandua and Venutius, for which Tacitus is again the (only) source, may have provided a pretext for the Roman army to begin the conquest of the whole of northern Britain ( Histories III, 45). England south of Hadrian’s Wall, including Yorkshire, was to remain part of the Roman Empire for about 340 years. The region which is the principal subject of this book is Yorkshire as it was defined before local government reorganisation in 1974. There was no political entity corresponding to the county in Roman times. It was, according to the second century Greek geographer Ptolemy, split between the Brigantes and the Parisi, a people who lived in what is now (after a brief period as Humberside) the East Riding. -

The Economic Rationale for Devolving to Yorkshire

Final Report 25 September 2018 The economic rationale for devolving to Yorkshire Hull City Council, on behalf of 18 Yorkshire Councils Our ref: 233-352-01 Final Report 25 September 2018 The economic rationale for devolving to Yorkshire Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Economic Development Hull City Council, on behalf of 18 Yorkshire Councils 61 Mosley Street The Guildhall, Manchester M2 3HZ Alfred Gelder Street, Hull HU1 2AA +44 (0)161 261 9154 www.steer-ed.com Our ref: 233-352-01 Steer Economic Development has prepared this material for Hull City Council, on behalf of 18 Yorkshire Councils. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer Economic Development has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer Economic Development shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer Economic Development for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer Economic Development has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The economic rationale for devolving to Yorkshire | Final Report Contents 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................... i Headlines ............................................................................................................................ -

Spracklen, K (2019) Cycling, Bread and Circuses? When Le Tour Came to Yorkshire and What It Left Behind

Citation: Spracklen, K (2019) Cycling, bread and circuses? When Le Tour came to Yorkshire and what it left behind. Sport in Society. ISSN 1743-0437 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1673735 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/6152/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Sport and Society on 10 Oct 2019, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/17430437.2019.1673735 The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Cycling, Bread and Circuses? When Le Tour Came to Yorkshire and What It Left Behind Introduction Le Tour de France is the most famous and most prestigious professional men’s cycling event (Berridge 2012; Ferbrache 2013; Lamont 2014; Paramio-Salcines, Barquín, and Arroyo 2017; Smith 2008). -

Travel and Tourism Additi Onal Apprenti Ceships and Training Courses

strategy to bring in 4 million extra overseas visitors over thenext four years, making the most of opportuniti es such as the 2012 Olympics and Diamond Jubilee. Plain Guide to • The Government wants to increase domesti c tourism, boost visitor expenditure and help UK tourism compete more eff ecti vely in the internati onal market. It Employment and Skills also wants to increase numbers of UK residents holidaying at home. This could create 50,000 new jobs across the UK. • Aims are to improve producti vity and staff and management skills through Travel and Tourism additi onal apprenti ceships and training courses. • Also to use new technology such as i-phones and android apps as well as This leafl et covers travel and tourist services but the wider tourism industry includes websites, to widen access to tourist informati on and availability in diff erent hotels and self-catering holiday accommodati on, restaurants, catering services and languages. visitor att racti ons. It is closely linked with passenger transport such as airlines, • Tourist Boards may change with the Government and private tourist fi rms (e.g. cruise ships, ferries, railways, coaches. See also the Plain Guide leafl ets on Catering hotels, restaurants) co-operati ng with each other to promote visitor desti nati ons and Hospitality and Driving Jobs. across the UK. • A new industry taskforce will look at cutti ng ‘red tape’ and regulati ons which Typical job ti tles include: may be holding the industry back. Travel agent/adviser Resort representati ve • People 1st and GoSkills Sector Skills Councils have merged to achieve a more Travel consultant Tour manager/courier integrated approach to passenger transport operati ons, travel and tourism to Travel agency manager Tourism offi cer provide a bett er welcome for visitors. -

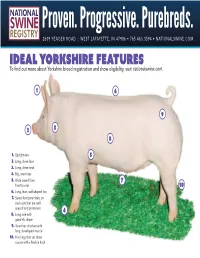

Yorkshire Features to find out More About Yorkshire Breed Registration and Show Eligibility, Visit Nationalswine.Com

Proven. Progressive. Purebreds. 2639 YEAGER ROAD :: WEST LAFAYETTE, IN 47906 • 765.463.3594 • NATIONALSWINE.COM Ideal yorkshire Features To find out more about Yorkshire breed registration and show eligibility, visit nationalswine.com. 1 6 9 2 3 8 1. Upright ears 5 2. Long, clean face 3. Long, clean neck 4. Big, even toes 5. Wide based from 7 front to rear 10 6. Long, lean, well-shaped top 7. Seven functional teats on each side that are well spaced and prominent 4 8. Long side with good rib shape 9. Good hip structure with long, developed muscle 10. Hind legs that set down square with a flexible hock Yorkshire AMERICA’S MATERNAL BREED Yorkshire boars and gilts are utilized as Grandparents (GP) in the production of F1 parent stock females that are utilized in a ter- minal crossbreeding program. They are called “The Mother Breed” and excel in litter size, birth and weaning weight, rebreeding interval, durability and longevity. They produce F1 females that exhibit 100% maternal heterosis when mated to a Landrace. Yorkshire breeders have led the industry in utilization History of the Yorkshire Breed of the "STAGES™" genetic evaluation program. From Yorkshires are white in color and have erect ears. They are 1990-2006, Yorkshire breeders submitted over 440,000 the most recorded breed of swine in the United States growth and backfat records and over 320,000 sow and in Canada. They are found in almost every state, productivity records. This represents the largest source with the highest populations being in Illinois, Indiana, of documented performance records in the world. -

Ripon City Plan Submission Draft

Submission Draft Plan Supporting Document D Supporting the Ripon Economy Ripon City Plan Submission Draft Supporting Document: Supporting the Ripon Economy March 2018 Submission Draft Plan Supporting Document D Supporting the Ripon Economy Contents 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 2 National Planning Context .................................................................................................. 2 2.1 National Planning Policy Framework................................................................................. 2 2.2 Planning Practice Guidance ............................................................................................... 4 3 Local Planning Authority Context ........................................................................................ 9 3.1 Harrogate District Local Plan – February 2001 (Augmented Composite) ......................... 9 3.2 Harrogate District Local Development Framework – Core Strategy ............................... 16 3.3 Harrogate District Local Plan: Draft Development Management Policies ...................... 21 3.4 Harrogate District Draft Local Plan .................................................................................. 23 4 Ripon City Plan Vision and Objectives ............................................................................... -

The Industrial Archaeology of West Yorkshire

The Industrial Archaeology of West Yorkshire Introduction: The impact of the Industrial Revolution came comparatively late to the West Yorkshire region. The seminal breakthroughs in technology that were made in a variety of industries (e.g. coal mining, textile, pottery, brick, and steam engine manufacture) during the 17th and 18th centuries, and the major production centres that initially grew up on the back of these innovations, were largely located elsewhere in the country. What distinguishes Yorkshire is the rate and density at which industry developed in the region from the end of the 18th century. This has been attributed to a wide variety of factors, including good natural resources and the character of the inhabitants! The portion of the West Riding north and west of Wakefield had become one of most heavily industrialised areas in the Britain by the end of the 19th century. It was also one of the most varied - there were some regional specialities, but at one time or another Yorkshire manufacturers supplied everything from artificial manure to motorcars. A list of local products for the 1890s would run into hundreds of items. Textile Manufacturing: The most prominent industry in the region has always been textile manufacture. There was a long tradition in the upland areas of the county of cloth production as a home-based industry, which supplemented farming. The scale of domestic production could hardly be considered negligible - the industry in Calderdale was after all so large that in 1779 it produced the Piece Hall in Halifax as an exchange centre and market. However, the beginnings of the factory system, and the birth of modern textile mills, dates to the introduction of mass-production techniques for carding and spinning cotton. -

Defra Statistics: Agricultural Facts – Yorkshire & the Humber

Defra statistics: Agricultural facts – Yorkshire & the Humber (commercial holdings at June 2019 (unless stated) The Yorkshire & the Humber region comprises the East Riding, Kingston upon Hull, N & NE Lincolnshire, City of York, North Yorkshire, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire. Parts of the Peak District, Yorkshire Dales and North York Moors National Parks are within the region. For the Yorkshire & the Humber region: Total Income from Farming increased by 26% between 2015 and 2019 to £452 million. The biggest contributors to the value of the output (£2.5 billion), which were pigs for meat (£382 million), wheat (£324 million), poultry meat (£267 million) and milk (£208 million), together account for 48%. (Sourced from Defra Aggregate agricultural accounts) In the Yorkshire & the Humber the average farm size in 2019 was 93 hectares. This is larger than the English average of 87 hectares. Predominant farm types in the Yorkshire & the Humber region in 2019 were Grazing Livestock farms and Cereals farms which accounted for 32% and 30% of farmed area in the region. Although Pig farms accounted for a much smaller proportion of the farmed area, the region accounted for 37% of the English pig population. Land Labour Yorkshire & England Yorkshire & England the Humber the Humber Total farmed area (thousand 1,136 9,206 Total Labour(a) hectares People: 32,397 306,374 Average farm size (hectares) 93 87 Per farm(b) 2.7 2.9 % of farmed area that is: Regular workers Rented (for at least 1 year) 33% 33% People: 7,171 68,962 Arable area(a) 52% 52% Per farm(b) 0.6 0.6 Permanent pasture 35% 36% Casual workers (a) Includes arable crops, uncropped arable land and temporary People: 2,785 45,843 grass. -

Apartment 4, Waterside, Ripon, North Yorkshire, HG4 1RA Asking Price

Apartment 4, Waterside, Ripon, North Yorkshire, HG4 1RA Asking price £139,950 www.joplings.com Apartment 4 is a Ground Floor Apartment available in the popular Waterside development, near the River Skell and is within reasonable walking distance of Ripon City Centre and nearby picturesque river walks. The property enjoys the benefits of gas central heating, double glazing, designated parking space and river views. www.joplings.com DIRECTIONS the apartments above. PARKING From the centre of Ripon proceed down Duck Hill PERSONAL ENTRANCE One allocated Parking space to the Front of the and left onto Water Skellgate. At the roundabout property. To the rear of the Ground Floor there is a Private turn right onto King Street and continue over the Entrance door leading to 4 Waterside. bridge. Take the first right onto Waterside and the COUNCIL TAX property can be found on the right hand side. HALLWAY Council Tax Band C A BIT ABOUT RIPON Personal security entrance phone. Security alarm. SERVICES Consumer unit. Ripon is the third smallest city in England and is Mains Water known for the imposing Cathedral, Ripon LIVING ROOM Electricity Drainage Racecourse and the nearby, Fountains Abbey and Windows out onto the Front of the property. Gas central heating Studley Royal Gardens. Ripon Market Place is at Access through to the ... the centre of the City with a variety of local shops ADDITIONAL INFORMATION and amenities within easy walking distance. It also KITCHEN The Vendor has informed us that the length of the benefits from a variety of Primary Schools which Window to the Front of the property. -

Tour De Yorkshire 2019 Economic Impact Assessment Report For

Tour de Yorkshire – Economic Impact Assessment 2019 Tour de Yorkshire 2019 Economic Impact Assessment Report for Welcome to Yorkshire By Dr Kyriaki Glyptou, Dr Peter Robinson and Robin Norton (GRASP) © Leeds Beckett University (June, 2019) School of Events, Tourism and Hospitality Management, Leeds Beckett University Headingley Campus, Macaulay Hall, Headingley, Leeds, LS6 3QN, United Kingdom. 1 Tour de Yorkshire – Economic Impact Assessment 2019 Contacts Client Sponsor: Welcome to Yorkshire Contact at Welcome to Yorkshire Contact: Danielle Ramsey Position: Marketing Campaigns Manager T: 0113 322 3547 M: 07738 854 463 Email: [email protected] Address: Dry Sand Foundry, Foundry Square, Holbeck, Leeds, LS11 5DL Contact at Leeds Beckett University Contact: Peter Robinson T: 0113 812 4497 Email: [email protected] Address: Leeds Beckett University, Macauley Hall, Headingley, Leeds LS6 3QN 2 Tour de Yorkshire – Economic Impact Assessment 2019 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Figure 1.1 Tour De Yorkshire Attendance ....................................................................................... 5 Table 1.1 Estimated Revenue Assessment of the 2019 Tour de Yorkshire..................................... 5 1.2 Possible Causes of Difference in -

Marketing for Tourism Provides an Introduction to the Theory Of

Marketing for Tourism provides an introduction to the theory of Marketing for marketing and its application in the various sectors of the travel and for Marketing fourth edition tourism industry. This leading text has been fully revised and updated to Tourism take account of recent changes within this dynamic environment. J Christopher Holloway The fourth edition provides a wide international dimension, notably in the 13 longer case studies at the end of the text. A brand new section shows full colour illustrations of recent advertising and promotional strategies. There is broad-ranging coverage of key issues such as branding, CRM, Marketing for sustainability and the changing patterns of distribution in this fast- fourth edition moving industry. A strong pedagogical structure throughout the book includes learning Tourism objectives, mini cases, and end-of-chapter questions and issues for T discussion. Clearly laid out and accessibly written, the book is ideal for ourism students taking modules on marketing for tourism within undergraduate and masters-level degrees in Tourism, Hospitality, Marketing and Business Studies. J Christopher Holloway Key Features • Range of brand new and international cases f • Coverage of relationship marketing, branding and sustainability ourth edition • Impacts of new technologies, internet and e-marketing • Thorough update, particularly of tour operating and retail environments • New chapter on the sales function • Website provides a selection of presentation slides at www.booksites.net/holloway Holloway Chris Holloway was formerly Professor of Tourism Management, University of the West of England. www.pearson-books.com an imprint of Marketing for Tourism We work with leading authors to develop the strongest educational materials in leisure and tourism, bringing cutting-edge thinking and best learning practice to a global market. -

TOURISM PANEL Venue

TOURISM PANEL Venue: Town Hall, Date: Monday, 16th March, 2009 Moorgate Street, Rotherham. Time: 2.00 p.m. A G E N D A 1. To determine if the following items are likely to be considered under the categories suggested in accordance with Part I of Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972 (as amended March 2006). 2. To determine any item which the Chairman is of the opinion should be considered as a matter of urgency. 3. Apologies for Absence. 4. Minutes of the previous meeting held on 15th January, 2009. (copy attached) (Pages 1 - 7) 5. Matters Arising. 6. Wath Festival - Presentation. David Roche and Rachel Oliver, Wath Festival. 7. Items raised by Industry Representatives:- (a) Clifton Park Developments and Promotion (b) Review of Tourism in Yorkshire (c) Working in partnership with the down turn in the economic climate 8. Forthcoming events giving assistance to/in the Borough. Joanne Edley, Tourism Manager, to report. 9. Tourism Service and Visitor Centre/Tourist Information Centre from April 2009 - decisions regarding resources. Marie Hayes, Events and Promotions Service Manager, to report. 10. Review of the Tourism Service delivery of the Draft Visitor Economy Plan 2008/2009. (report attached) (Pages 8 - 27) Joanne Edley, Tourism Manager, to report. 11. Walking Festival 2009. (report attached) (Pages 28 - 30) Joanne Edley, Tourism Manager, to report. 12. Any Other Business. 13. To agree the Date, Time and VenueTH for the next meeting. To consider:- MONDAY, 27 APRIL, 2009 at 2.00 p.m. at the Town Hall, Moorgate Street, Rotherham. Page 1 Agenda Item 4 1 TOURISM PANEL - 15/01/09 TOURISM PANEL THURSDAY, 15TH JANUARY, 2009 Present:- Councillor Smith (in the Chair); Councillors Boyes, Doyle, McNeely and Whelbourn.