CSPAN/FIRST LADIES FLORENCE HARDING JUNE 16, 2014 10:00 A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit All of the Historic Sites and Museums! Ohiohistory.Org

Visit all of the historic sites and museums! ohiohistory.org ohiohistory.org • 800.686.6124 35. Fort Ancient Earthworks & Nature Preserve Museum/ Historic Buildings Mounds/ Monument/ Natural Area/ Gift Picnicking NORTHEAST Site Name Restrooms Average Visit 6123 State Route 350, Oregonia 45054 • 800.283.8904 v 190910 Visitor Center Open to Public Earthworks Gravesite Trails (miles) Shop (*shelter) Explore North America’s largest ancient hilltop enclosure, built 15. Custer Monument 1 Armstrong Air & Space Museum 2+ hours 2,000 years ago. Explore an on-site museum, recreated American State Route 646 and Chrisman Rd., New Rumley • 866.473.0417 Indian garden, and miles of hiking trails with scenic overlooks. 2 Cedar Bog Nature Preserve 1 2+ hours Visit the site of George Armstrong Custer’s birthplace and see the monument to the young soldier whose "Last Stand" made him a 36. Fort Hill Earthworks & Nature Preserve 3 Cooke-Dorn House 1 1+ hours household name. 13614 Fort Hill Rd., Hillsboro 45133 • 800.283.8905 Visit one of the best-preserved American Indian hilltop enclosures Ohio. of 4 Fallen Timbers Battlefield Memorial Park 1+ hours 16. Fort Laurens in North America and see an impressive variety of bedrock, soils, 11067 Fort Laurens Rd. NW (CR 102), Bolivar 44612 • 800.283.8914 flora and fauna. history fascinating and varied the life to bring help to 5 Fort Amanda Memorial Park 0.25 * 1+ hours Explore the site of Ohio’s only Revolutionary War fort, built in 1778 groups local these with work to proud is Connection 37. Harriet Beecher Stowe House History Ohio The communities. -

Niall Palmer

EnterText 1.1 NIALL PALMER “Muckfests and Revelries”: President Warren G. Harding in Fact and Fiction This article will assess the development of the posthumous reputation of President Warren Gamaliel Harding (1921-23) through an examination of key historical and literary texts in Harding historiography. The article will argue that the president’s image has been influenced by an unusual confluence of factors which have both warped history’s assessment of his administration and retarded efforts at revisionism. As a direct consequence, the stereotypical, deeply negative, portrait of Harding remains rooted in the nation’s consciousness and the “rehabilitation” afforded to many presidents by revisionist writers continues to be denied to the man still widely-regarded as the worst president of the twentieth century. “Historians,” Eugene Trani and David Wilson observed in 1977, “have not been gentle with Warren G. Harding.”1 In successive surveys of American political scientists, historians and journalists, undertaken to rank presidents by achievement, vision and leadership skills, the twenty-ninth president consistently comes last.2 The Chicago Sun- Times, publishing the findings of fifty-eight presidential historians and political scientists in November 1995, placed Warren Harding at the head of the list of “The Ten Worst” Niall Palmer: Muckfests and Revelries 155 EnterText 1.1 Presidents.3 A 1996 New York Times poll branded Harding an outright “failure,” alongside two presidents who presided over the pre-Civil War crisis, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. The academic merit and methodological underpinnings of such surveys are inevitably flawed. Nonetheless, in most cases, presidential status assessments are fluid, reflecting the fluctuations of contemporary opinion and occasional waves of academic revisionism. -

Dead Last: the Public Memory of Warren G. Harding's Scandalous

Payne.1-19 11/13/08 3:02 PM Page 1 Questions Asked Democracy has no monuments. It strikes no medals. It bears the head of no man on a coin. —John Quincy Adams To enter into any serious historical criticism of these stories [regarding George Washington’s childhood] would be to break a butterfly. 1 —Henry Cabot Lodge Harding and the Log Cabin Myth Warren G. Harding’s story is an American myth gone wrong. As our twenty-ninth president, Harding occupied the office that stands at the symbolic center of American national identity.1 Harding’s biography should have easily slipped into American history and mythology when he died in office, on August 2, 1923. Having been born to a humble midwestern farm family, what better ending could there be to his story than death in the service of his nation? What stronger image could stand as a lasting tribute than grieving citizens lining the railroad tracks, as they had for Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley, to view Har- ding’s body? The public grief that accompanied the passing of Harding’s burial train would seem to have foreshadowed a positive place in the national memory. Warren and Florence Harding were laid to rest in a classically designed marble mau- soleum in their hometown of Marion, Ohio, a mausoleum that was the last great memorial in the older style popular before the rise of presidential libraries. However, the near perfection Payne.1-19 11/13/08 3:02 PM Page 2 Dead Last of his political biography and his contemporary popularity did not follow him into history. -

Team Players: Triumph and Tribulation on the Campaign Trail

residential campaigns that celebrate our freedom to choose a leader by election of the people are events P unique to our country. It is an expectant, exciting time – a promise kept by the Constitution for a better future. Rituals developed over time and became traditions of presidential hopefuls – the campaign slogans and songs, hundreds of speeches, thousands of handshakes, the countless miles of travel across the country to meet voters - all reported by the ever-present media. The candidate must do a balancing act as leader and entertainer to influence the American voters. Today the potential first spouse is expected to be involved in campaign issues, and her activities are as closely scrutinized as the candidate’s. However, these women haven’t always been an official part of the ritual contest. Campaigning for her husband’s run for the presidency is one of the biggest self-sacrifices a First Lady want-to-be can make. The commitment to the campaign and the road to election night are simultaneously exhilarating and exhausting. In the early social norms of this country, the political activities of a candidate’s wife were limited. Nineteenth-century wives could host public parties and accept social invitations. She might wave a handkerchief from a window during a “hurrah parade” or quietly listen to a campaign speech behind a closed door. She could delight the crowd by sending them a winsome smile from the front porch campaign of her own home. But she could not openly show knowledge of politics and she could not vote. As the wife of a newly-elected president, her media coverage consisted of the description of the lovely gown she wore to the Inaugural Ball. -

Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 562 CS 216 046 AUTHOR Smith, Nancy Kegan, Comp.; Ryan, Mary C., Comp. TITLE Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-911333-73-8 PUB DATE 1989-00-00 NOTE 189p.; Foreword by Don W. Wilson (Archivist of the United States). Introduction and Afterword by Lewis L. Gould. Published for the National Archives Trust Fund Board. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *Authors; *Females; Modern History; Presidents of the United States; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *First Ladies (United States); *Personal Writing; Public Records; Social Power; Twentieth Century; Womens History ABSTRACT This collection of essays about the Presidential wives of the 20th century through Nancy Reagan. An exploration of the records of first ladies will elicit diverse insights about the historical impact of these women in their times. Interpretive theories that explain modern first ladies are still tentative and exploratory. The contention in the essays, however, is that whatever direction historical writing on presidential wives may follow, there is little question that the future role of first ladies is more likely to expand than to recede to the days of relatively silent and passive helpmates. Following a foreword and an introduction, essays in the collection and their authors are, as follows: "Meeting a New Century: The Papers of Four Twentieth-Century First Ladies" (Mary M. Wolf skill); "Not One to Stay at Home: The Papers of Lou Henry Hoover" (Dale C. -

Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations

Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Prepared by Benjamin D. Rickey & Co. 593 South Fifth Street Columbus, Ohio 43206 May 2008 Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Table of Contents List of Organizations by County 3 Certified Local Government List by Community 28 Designated Regional Heritage Areas 31 Statewide Preservation Organizations 32 Designated Ohio Scenic Byways 32 Designated Ohio Main Street Communities 32 1 Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Introduction This list of historic preservation organizations in Ohio has been compiled from a variety of sources, including those provided by the Local History and the Ohio Historic Preservation Offices of the Ohio Historical Society, Heritage Ohio and Preservation Ohio (both statewide non-profit organizations). The author added information based on knowledge of the state and previous work with local and regional organizations. While every attempt was made to make the list comprehensive, it is likely that there are some omissions and the list should be updated periodically. 2 Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Windsor Historical Society Adams 5471 State Route 322 Windsor, OH 44099 Manchester Historical Society PO Box 1 Athens Manchester, OH 45144 Phone: (937) 549-3888 Athens County Historical Society & Museum Allen 65 N. Court St. Athens, OH 45701 Downtown Lima (740) 592.2280 147 North Main Street Lima, Ohio 45801 Nelsonville Historic Square Arts District (419) 222-6045 Athens County Convention and Visitors [email protected] Bureau 667 East State Street Swiss Community Historical Society Athens, OH 45701 P.O. Box 5 Bluffton, OH 45817 Auglaize Ashland Belmont Ashland County Chapter-OGS Belmont County Chapter-OGS PO Box 681 PO Box 285 Ashland, OH 44805 Barnesville, OH 43713 Ashtabula Brown Ashtabula County Genealogical Society Ripley Museum Geneva Public Library PO Box 176 860 Sherman St. -

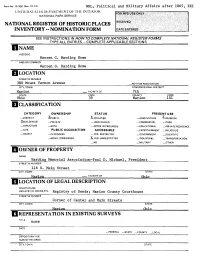

Iowner of Property

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Warren G. Harding Home AND/OR COMMON Warren G. Harding Home LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 380 Mount Vernon Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Marion . VICINITY OF 7th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Ohio 39 Marion 101 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT JKpUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ^.MUSEUM JKBUILDING(S) _ PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _ YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME ____Harding Memorial Associaiton-Paul D. Michael, President STREET & NUMBER 116 S. Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Marion VICINITY OF Ohio LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Registry of Deeds; Marion County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Corner of Center and Main Streets CITY, TOWN STATE Marion Ohio I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none DATE -FEDERAL —STATE __COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Warren G. Harding Home sits at 380 Mt. Vernon Avenue on the north side of the street. The House was designed by the Hardings one year before their marriage. It is a two and one-half story clapboard structure painted green. The front porch runs across the front facade and the foundation is Indiana limestone. -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER to HOST FIRST LADIES: POLITICAL ROLE and PUBLIC IMAGE Last Stop on Exhibit’S Nationwide Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ashley Berke Public Relations Manager 215.409.6693 [email protected] Downloadable images and complete press kit available at: www.constitutioncenter.org/PressRoom/ChangingExhibits/ For additional images, please visit: ftp://siteguest:[email protected]/ (username: sitesguest, password: 9getfiles9) NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER TO HOST FIRST LADIES: POLITICAL ROLE AND PUBLIC IMAGE Last Stop on Exhibit’s Nationwide Tour Philadelphia, PA – America’s first ladies have fascinated generations, influenced politics and style, advocated for social causes, and navigated an unpaid, unelected, and difficult role. From October 5 through December 31, 2007, the National Constitution Center will host First Ladies: Political Role and Public Image. From the exuberant Dolley Madison and troubled Mary Todd Lincoln, to the humanitarian Eleanor Roosevelt and the intriguing wives of our recent presidents, the exhibition celebrates the remarkable individuals who have occupied this demanding post. The showing of First Ladies at the National Constitution Center is the last stop on the exhibit’s national tour. First Ladies is based on one of the Smithsonian’s most visited permanent exhibitions and contains artifacts from the rarely traveled first ladies collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, Behring Center. Organized by the National Museum of American History and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES), First Ladies is made possible by A&E Network. Macy’s is the local presenting sponsor and NBC 10 is the official media partner for the Center’s showing of First Ladies. -MORE- ADD ONE/FIRST LADIES EXHIBITION The exhibition features more than two centuries of elegant inaugural and evening gowns, clothing and jewelry, White House furnishings and china, photographs and portraits, and campaign and personal memorabilia. -

65Th MEETING

1 United States Mint Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee Meeting Friday April 19, 2013 The Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee met in Hearing Room 220 South at 801 9th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C., at 9:00 a.m., Gary Marks, Chair, presiding. 2 Members Present: Gary Marks, Chair Erik Jansen Michael Moran Michael Olson Michael A. Ross Donald Scarinci Jeans Stevens-Sollman Thomas J. Uram Heidi Wastweet United States Mint Staff Present Richard A. Peterson, Acting Director Steve Antonucci Betty Birdsong Don Everhart Gwen Mattleman Bill Norton April Stafford Megan Sullivan Greg Weinman Also Present: Kathy Dillaber John Feal Sandy Felt Arthur Houghton Paula Jacobs Laurie Laychak Carole O’Hare* *Participating via telephone 3 Contents Welcome and Call to Order 5 Gary Marks 5 Discussion of Letter and Minutes from Previous Meeting 5 Gary Marks 5 Review and Discuss Candidate Reserves Designs for the 2014 Presidential $1 Coin Program 6 April Stafford, Megan Sullivan, and Don Everhart 6 Review and Discuss Candidate Reserves Designs from the Edith Wilson 2013 First Spouse Bullion Coin 23 April Stafford, Megan Sullivan, and Don Everhart 23 Review and Discuss Themes for the 2014 First Spouse Bullion Coin Program 33 April Stafford and Megan Sullivan 33 Review and Discuss Candidate Designs for the Code Talker Recognition Congressional Medal Program (Muscogee Creek Nation) 50 April Stafford, Betty Birdsong, and Don Everhart 50 Approval of the FY12 Annual Report 62 Gary Marks 62 Resolution 2013-01: Recommending an American Liberty Commemorative Coinage Program 68 Michael Moran 68 Review and Discuss Themes for Fallen Heroes of 9/11 Congressional Gold Medals 83 4 April Stafford 83 Sandy Felt 85 Laurie Laychak 87 Megan Sullivan 88 Carole O'Hare 91 Paula Jacobs 91 Kathy Dillaber 93 Wrap up and Adjourn 101 5 Proceedings (9:12 a.m.) Welcome and Call to Order Gary Marks Chair Marks: Good morning. -

Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 143–65

NOTES Introduction 1. On the formidable mythology of the Watergate experience, see Michael Schudson, The Power of News (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 143–65. 2. Adam Gropkin, “Read All About It,” New Yorker, 12 December 1994, 84–102. Samuel Kernell, Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leader- ship, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 1993), 55–64, 192–6. 3. Michael Baruch Grossman and Martha Joynt Kumar, Portraying the Presi- dent:The White House and the News Media (Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981), 19–28. See also Stephen Hess, The Government- Press Connection (Washington, D.C.: Brookings, 1984). 4. Kenneth T.Walsh, Feeding the Beast:The White House versus the Press (New York:Random House, 1996), 6–7. 5. Thomas E. Patterson,“Legitimate Beef:The Presidency and a Carnivorous Press,” Media Studies Journal 8 (No. 2, Spring 1994): 21–6. 6. See, among others, Robert Entman, Democracy without Citizens: Media and the Decay of American Politics (New York: Oxford, 1989), James Fallows, Breaking the News (New York: Pantheon, 1996), and Thomas E. Patterson, Out of Order (New York:Vintage, 1994). 7. Larry J. Sabato, Feeding Frenzy: How Attack Journalism Has Transformed Poli- tics (New York: Free Press, 1991) is credited with popularizing use of the phrase. 8. See, generally, John Anthony Maltese, Spin Control:The White House Office of Communications and the Management of Presidential News, 2nd ed. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994). 9. Jennifer Waber,“Secrecy and Control: Reporters Committee says Clinton Administration’s dealings with the press have become more antagonistic,” Editor and Publisher, 24 May 1997, 10–13, 33–4. -

Activity Book Navigating the Bill Process

Activity Book Navigating the Bill Process 2 Know Your Presidents Can you find all these words in the crossword above? ADAMS GARFIELD LINCOLN ROOSEVELT GRANT ARTHUR MADISON TAFT HARDING BUCHANAN MCKINLEY TAYLOR BUSH HARRISON MONROE TRUMAN CLEVELAND HAYES NIXON TRUMP HOOVER CLINTON OBAMA TYLER COOLIDGE JACKSON PIERCE VANBUREN EISENHOWER JEFFERSON POLK WASHINGTON JOHNSON FILLMORE REAGAN WILSON FORD KENNEDY Bonus: Several Presidents shared the same last name – how many do you know? names) five (Hint: 3 Know Your Civics Can you find all these words in the crossword above? AMERICA GOVERNOR POLLING BALLOT HOUSE PRESIDENT BILL JUDICIAL PUBLIC HEARING CANDIDATE LAW PUBLIC POLICY CAPITOL LEGISLATURE REPRESENTATIVE CIVICS MAYOR SENATE COMMITTEE NATION SENATOR CONGRESS NONPARTISAN UNITED STATES COUNTRY POLITICAL TESTIMONY ELECTION POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE VOTE GOVERNMENT POLITICAL PARTY WHITE HOUSE 4 U.S. Citizenship Practice Test Could you pass the U.S. Citizenship test? Take these practice questions from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to find out! 1. Name the US war between the North and the South. a. World War I b. The Civil War c. The War of 1812 d. The Revolutionary War 2. What is one thing Benjamin Franklin is famous for? a. U.S. diplomat b. Youngest member of the Constitutional Convention c. Third President of the United States d. Inventor of the Airplane 3. Who did the United States fight in World War II? a. The Soviet Union, Germany, and Italy b. Austria-Hungary, Japan, and Germany c. Japan, China, and Vietnam d. Japan, Germany, and Italy 4. Who signs bills to become laws? a. The Secretary of State b.