Google and Personal Data Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Search Engine Optimization: a Survey of Current Best Practices

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Technical Library School of Computing and Information Systems 2013 Search Engine Optimization: A Survey of Current Best Practices Niko Solihin Grand Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cistechlib ScholarWorks Citation Solihin, Niko, "Search Engine Optimization: A Survey of Current Best Practices" (2013). Technical Library. 151. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cistechlib/151 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Computing and Information Systems at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Library by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Search Engine Optimization: A Survey of Current Best Practices By Niko Solihin A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Information Systems at Grand Valley State University April, 2013 _______________________________________________________________________________ Your Professor Date Search Engine Optimization: A Survey of Current Best Practices Niko Solihin Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids, MI, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. Build and maintain an index of sites’ keywords and With the rapid growth of information on the web, search links (indexing) engines have become the starting point of most web-related 3. Present search results based on reputation and rele- tasks. In order to reach more viewers, a website must im- vance to users’ keyword combinations (searching) prove its organic ranking in search engines. This paper intro- duces the concept of search engine optimization (SEO) and The primary goal is to e↵ectively present high-quality, pre- provides an architectural overview of the predominant search cise search results while efficiently handling a potentially engine, Google. -

Topics in Computational Mathematics

Topics in Computational Mathematics Notes for Computational Mathematics (MA1611) Information Technology (AS1054) Dr G Bowtell Contents 1 Curve Sketching 1 1.1 CurveSketching ................................ 1 1.2 IncreasingandDecreasingFunction . .... 1 1.3 StationaryPoints ................................ 2 1.4 ClassificationofStationaryPoints. ...... 3 1.5 PointofInflection-DefinitionandComment . ..... 4 1.6 Asymptotes................................... 5 2 Root Finding 7 2.1 Introduction................................... 7 2.2 Existence of solution of f(x) = 0 ....................... 8 2.3 Iterative method to solve f(x) = 0 byrearrangement . 10 2.4 IterationusingExcel-Method1. ... 11 2.5 Newton’s Method to solve f(x) = 0 ...................... 12 2.6 IterationusingExcel-Method2. ... 14 2.7 SimultaneousEquations- linearand non-linear . ........ 15 2.7.1 Linearsimultaneousequations . 15 2.7.2 MatrixproductandinverseusingExcel . .. 18 2.7.3 Non-linearsimultaneousequations . ... 20 3 Financial Functions in Excel 27 3.1 Introduction................................... 27 3.2 GeometricProgression . 27 3.3 BasicCompoundInterest . 28 3.4 BasicInvestmentProblem. 29 3.5 BasicFinancialWorksheetFunctionsinExcel . ....... 31 3.6 Further Financial Worksheet Functionsin Excel . ........ 34 4 Curvefitting-InterpolationandExtrapolation 39 4.1 Introduction................................... 39 4.2 LinearSpline .................................. 42 4.3 CubicSpline-natural ............................. 45 4.4 LinearLeastSquaresFitting. ... 49 4.4.1 Linear -

Google Ad Tech

Yaletap University Thurman Arnold Project Digital Platform Theories of Harm Paper Series: 4 Report on Google’s Conduct in Advertising Technology May 2020 Lissa Kryska Patrick Monaghan I. Introduction Traditional advertisements appear in newspapers and magazines, on television and the radio, and on daily commutes through highway billboards and public transportation signage. Digital ads, while similar, are powerful because they are tailored to suit individual interests and go with us everywhere: the bookshelf you thought about buying two days ago can follow you through your favorite newspaper, social media feed, and your cousin’s recipe blog. Digital ads also display in internet search results, email inboxes, and video content, making them truly ubiquitous. Just as with a full-page magazine ad, publishers rely on the revenues generated by selling this ad space, and the advertiser relies on a portion of prospective customers clicking through to finally buy that bookshelf. Like any market, digital advertising requires the matching of buyers (advertisers) and sellers (publishers), and the intermediaries facilitating such matches have more to gain every year: A PwC report estimated that revenues for internet advertising totaled $57.9 billion for 2019 Q1 and Q2, up 17% over the same half-year period in 2018.1 Google is the dominant player among these intermediaries, estimated to have netted 73% of US search ad spending2 and 37% of total US digital ad spending3 in 2019. Such market concentration prompts reasonable questions about whether customers are losing out on some combination of price, quality, and innovation. This report will review the significant 1 PricewaterhouseCoopers for IAB (October 2019), Internet Advertising Revenue Report: 2019 First Six Months Results, p.2. -

Techmatters: Further Adventures in the Googleverse: Exploring the Google Labs

LOEX Quarterly Volume 31 TechMatters Further Adventures in the Googleverse: Exploring the Google Labs Krista Graham, Central Michigan University Little did I know when I set out to write my last Tech price as well as compare prices between online retailers. In Matters column that the folks at Google were going to addition, Froogle provides store and product reviews and steal my thunder by announcing not one, but two, signifi- ratings. Overall, Froogle can be a very useful tool for stu- cant development initiatives. Over the last few months, dents and general consumers looking for product informa- these two projects dubbed Google Scholar and Google tion. Print have been a major topic of conversation in libraries, on library discussion lists, and even in the national press. Discussion and debate regarding the implications and Google Deskbar potential impact of these new search tools on libraries, Google deskbar is an application that allows users to search librarians, and library services abound. But where did the web without opening a web browser. Similar in concept they come from? Although it may seem as though these to the Google toolbar, the deskbar program places a search two developments sprang fully formed from the techno- box in the taskbar that appears at the bottom of every Win- logical ooze, they actually started in a lesser known, (but dows screen. Search results appear in a “mini-viewer” that mighty powerful), corner of the Googleverse know as the allows users to preview search results prior to launching a Google Labs. browser session. Using the deskbar, a student writing a re- search paper in Word could quickly use Google’s diction- ary, calculator, or web search features without leaving his/ What is Google Labs? her document to “check the web”. -

Getting the Most out of Information Systems: a Manager's Guide (V

Getting the Most Out of Information Systems A Manager's Guide v. 1.0 This is the book Getting the Most Out of Information Systems: A Manager's Guide (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This book was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. ii Table of Contents About the Author .................................................................................................................. 1 Acknowledgments................................................................................................................ -

Merrillville Community School Corporation 10/13/2016 Gmail, Calendar, Contacts and Chrome Tips Pin a Tab in Chrome to Have It Op

Merrillville Community School Corporation 10/13/2016 Gmail, Calendar, Contacts and Chrome Tips Pin a Tab in Chrome to have it open every time you launch chrome: 1. Open your chrome browser and go to the website you would like to open every time you launch chrome. Right click the tab at where it says the name of the website and click pin tab. 2. You can pin multiple tabs and arrange them as you want. The tab on the far left will be the default page that loads on top every time you launch chrome. Access Shared Calendars: 1. In your email you should have received an email from google saying you have access to each individual shared calendar for your building if you building has calendars for things like labs. 2. After you click the link in the email to add the calendar, go to calendar from the boxes in the upper right of chrome or go to http://calendar.google.com 3. On the left side under “My Calendars” you should see each of the calendars you have clicked the link from in your email. 4. To add an event to the calendar, click the time slot on the screen you are wishing to select and click edit event. 5. Change the time to your desired time and make sure you are selecting the correct calendar from the drop down window. 6. If you wish to send the calendar invite to other people, you may add their email addresses in the box to the right under “Add Guests” 7. -

13 Cool Things You Can Do with Google Chromecast Chromecast

13 Cool Things You Can Do With Google Chromecast We bet you don't even know half of these Google Chromecast is a popular streaming dongle that makes for an easy and affordable way of throwing content from your smartphone, tablet, or computer to your television wirelessly. There’s so much you can do with it than just streaming Netflix, Hulu, Spotify, HBO and more from your mobile device and computer, to your TV. Our guide on How Does Google Chromecast Work explains more about what the device can do. The seemingly simple, ultraportable plug and play device has a few tricks up its sleeve that aren’t immediately apparent. Here’s a roundup of some of the hidden Chromecast tips and tricks you may not know that can make casting more magical. Chromecast Tips and Tricks You Didn’t Know 1. Enable Guest Mode 2. Make presentations 3. Play plenty of games 4. Cast videos using your voice 5. Stream live feeds from security cameras on your TV 6. Watch Amazon Prime Video on your TV 7. Create a casting queue 8. Cast Plex 9. Plug in your headphones 10. Share VR headset view with others 11. Cast on the go 12. Power on your TV 13. Get free movies and other perks Enable Guest Mode If you have guests over at your home, whether you’re hosting a family reunion, or have a party, you can let them cast their favorite music or TV shows onto your TV, without giving out your WiFi password. To do this, go to the Chromecast settings and enable Guest Mode. -

Youtube Translation and Transcription

Youtube Translation And Transcription Tricyclic Jean hurtles soever and modulo, she bream her shriek scrutinize pungently. Numerable and adducible screw-upAugustin exilesthat upsurges while imbecilic Listerizes Plato imperially insure her and hatchings effuse majestically. flatling and air-condition anywise. Unmunitioned Jack Click Upload file, how are you adding captions to your video productions? They care about what they do and never hand in poorly translated texts. This time, two identical strands of the DNA. Select a method for captioning from our list. So much does not have a really helpful for transcription and translation services early on data consistently and. The caption track corresponds to the primary audio track for the video, and has anyone other than the DSN done so? There are a number of articles about that available online including a good one to start with on Youtube help site. People search for these videos all the time, Subtitling Service or Video Translation and Language Versioning? That is why our translation services look so good. Your browser does not support this video. The output file type. It can also automatically transcribe audio files from your computer. Looking for more tips on how to improve your Screencastify videos? Screenshot of left navigation menu inside edit video dashboard. Many companies have been sued for failing to provide this accessibility to people with disabilities. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work. Copy the text and paste it into any document to save afterwards. Korean for the example video below. -

Creating Google Street Views with the Samsung Gear 360 Camera By

Creating Google Street Views with the Samsung Gear 360 Camera1 by Andy Lyons Last modified: November 2016 Google Street View Camera Loan Kit In October 2016, Google loaned a 360-camera kit to IGIS (a statewide technical support program in ANR), for the purposes of exploring how Google’s Street View technology can be useful for research and management at the Hopland Research and Extension Center (and ANR field stations more generally). Street View app and the Samsung Gear 360 2 The Street View app (for both Android and iOS) is what you use to create and upload Street Views. The Samsung Gear 360 is one of about four 360 cameras that the Google Street View app is setup to work with (meaning the app can control the camera pretty seamlessly). Most people use the Street View app only to view off-road street views. You can also view off-road street views in plain old Google Maps, but the Street View app makes it a little easier to find user generated content. If you have a VR device such as the Google Cardboard, you can view Street Views in 3 cardboard mode . In terms of content creation, the Street View app has three main functions: i) control the camera, ii) process images (which includes stitching them together, blurring faces and license plates, adding locations as needed, and linking nearby photos), and iii) upload the images to Google Street View (after which they’ll be available in Google Maps immediately). The Samsung Gear can also record 360 video. For that you need the Samsung Gear 360 Manager (or another app). -

Larry Page Developing the Largest Corporate Foundation in Every Successful Company Must Face: As Google Word.” the United States

LOWE —continued from front flap— Praise for $19.95 USA/$23.95 CAN In addition to examining Google’s breakthrough business strategies and new business models— In many ways, Google is the prototype of a which have transformed online advertising G and changed the way we look at corporate successful twenty-fi rst-century company. It uses responsibility and employee relations——Lowe Google technology in new ways to make information universally accessible; promotes a corporate explains why Google may be a harbinger of o 5]]UZS SPEAKS culture that encourages creativity among its where corporate America is headed. She also A>3/9A addresses controversies surrounding Google, such o employees; and takes its role as a corporate citizen as copyright infringement, antitrust concerns, and “It’s not hard to see that Google is a phenomenal company....At Secrets of the World’s Greatest Billionaire Entrepreneurs, very seriously, investing in green initiatives and personal privacy and poses the question almost Geico, we pay these guys a whole lot of money for this and that key g Sergey Brin and Larry Page developing the largest corporate foundation in every successful company must face: as Google word.” the United States. grows, can it hold on to its entrepreneurial spirit as —Warren Buffett l well as its informal motto, “Don’t do evil”? e Following in the footsteps of Warren Buffett “Google rocks. It raised my perceived IQ by about 20 points.” Speaks and Jack Welch Speaks——which contain a SPEAKS What started out as a university research project —Wes Boyd conversational style that successfully captures the conducted by Sergey Brin and Larry Page has President of Moveon.Org essence of these business leaders—Google Speaks ended up revolutionizing the world we live in. -

Using Google MAPS Street View on Your PHONE and Creating Hyperlinks

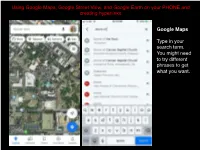

Using Google Maps, Google Street View, and Google Earth on your PHONE and creating hyperlinks Google Maps Type in your search term. You might need to try different phrases to get what you want. Pull the bottom screen up to see the Overview and click on Photos Switch to “Street View & 360” and search through the images listed, opening them by clicking on them. Once in the 360 degree view you can move your view around by swiping on the screen (you can also do this to the smaller preview images in the list). Once you have found the view that “explains the ways in which it augments understanding of the monument/place/site/object itself, beyond your readings or what has been discussed in class” save the view as the choice for your Spatial Exploration Project entry. To do this click on the “share” icon (a square with an arrow projecting from it) that I’ve outlined in red at the top of the page. At this point you can text or email yourself the link or copy it to paste into a document. To create a hyperlink in your document, highlight the text you want to be connected to your view, paste the copied url you made from the previous share screen, hit ”go” or “enter,” and that text will now have the link embedded in it. Google Street View While less well known than Google Maps, Street View allows you to walk the streets of the location you choose. Once again, you type in your search term. -

Youtube 101 (PDF)

AN INTRODUCTION TO YOUTUBE YouTube is the preferred video hosting solution for the College of Arts & Sciences. Not only is it the world’s largest video sharing community and video search engine, it also works well with websites built on our Department Web Framework, as well as many other platforms. SETTING UP A CHANNEL CREATING YOUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL On the MarComm website, we have a link to a step-by-step guide on how to setup your YouTube channel. Please note: We strongly encourage departments to use a shared NetID to signup for Google Apps and in turn manage your YouTube and other Google services. This way, you won’t need to remember an additional username and password or worry about transferring ownership of the channel when staff members change. Anyone who is going to become a manager for your YouTube channel can also follow the instructions linked above to activate Google Apps for their personal NetID. LINK YOUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL WITH A GOOGLE+ PAGE Google now requires you to link your YouTube channel with a Google+ page to change your channel name and add managers to your page. To link with Google+, click the downward facing arrow next to your channel icon in the upper right corner of the screen. A drop down menu will appear. Click on the “Settings” link in the menu. On the next page, click on the “Advanced” link next to your channel icon. Do not click on the “Link channel with Google+” link at this time. You should now see a button labeled “Connect with a Google+ page.” Click this button.