To View the Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Territory Election Results

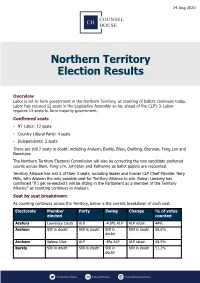

24 Aug 2020 Northern Territory Election Results Overview Labor is set to form government in the Northern Territory, as counting of ballots continues today. Labor has secured 12 seats in the Legislative Assembly so far, ahead of the CLP’s 3. Labor requires 13 seats to form majority government. Confirmed seats • NT Labor: 12 seats • Country Liberal Party: 4 seats • Independents: 2 seats There are still 7 seats in doubt, including Araluen, Barkly, Blain, Braitling, Brennan, Fong Lim and Namatjira. The Northern Territory Electoral Commission will also be correcting the two candidate preferred counts across Blain, Fong Lim, Johnston and Katherine as ballot papers are recounted. Territory Alliance has lost 2 of their 3 seats, including leader and former CLP Chief Minister Terry Mills, with Araluen the only possible seat for Territory Alliance to win. Robyn Lambley has confirmed “if I get re-elected I will be sitting in the Parliament as a member of the Territory Alliance” as counting continues in Araluen. Seat by seat breakdown: As counting continues across the Territory, below is the current breakdown of each seat. Electorate Member Party Swing Change % of votes elected counted Arafura Lawrence Costa ALP -4.0% ALP ALP retain 44% Araluen Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in Still in doubt 68.6% doubt Arnhem Selena Uibo ALP -8% ALP ALP retain 48.9% Barkly Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in Still in doubt 51.2% doubt Blain Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt 65% Braitling Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt -

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No. 144/17cncl TO: ORDINARY COUNCIL – MONDAY 11 SEPTEMBER 2017 SUBJECT: MAYOR’S REPORT 1. MEETINGS AND APPOINTMENTS 1.1 Lord Mayor of Darwin Katrina Fong Lim 1.2 Kerry Moir and Tony Tapsell, CEO LGANT 1.3 Terry-Ann Maney, Australian Institute of Company Directors 1.4 Stephen Nugent , Advisor to Minister for Tourism and Culture 1.5 Gary Powell, Regional Manager of Central Australia Indigenous Affairs Department, Prime Minister and Cabinet 1.6 Chief Minister Michael Gunner 1.7 Gary Higgins MLA, Leader of the Opposition 1.8 Steve Moore, CEO Barkly Regional Council 1.9 Tony Tapsell, CEO LGANT 1.10 Mayor David O’Loughlin, ALGA President 1.11 Steve Edgington, President Barkly Regional Council 1.12 City of Darwin Lord Mayor Kon Vataskallis 1.13 The Hon. Nicole Manison, NT Treasurer and Richard O’Leary, Advisor 1.14 Alice Springs Town Council – Planning for Great Northern Clean Up 1.15 Ian Coleman, Curator Olive Pink Botanic Garden 1.16 Craig Markham, Paul Tottani, Councillor de Brenni and Dale McIver 1.17 Susan Bradbrook, Governance Institute Australia 1.18 Judith Dixon – Central Australian Development Office 1.19 The Hon. Lauren Moss, Minister for Tourism and Culture 1.20 Chansey Paech MLA, Member for Namatjira 1.21 Litchfield Council Mayor Maree Bredhauer 1.22 Steve Hennessy, Northern Territory Grants Commission 1.23 Boulia Shire Mayor Rick Britton – Outback Way AGM 2. FUNCTIONS ATTENDED 2.1 Red CentreNATS – Volunteers and Officials Welcome, Star of Alice 2.2 Welcome Reception – Red CentreNATS, Alice Springs Convention Centre 2.3 St Philip’s College Musical – Little Women 2.4 Heritage Council Lunch, Mercure Hotel Alice Springs 2.5 Charles Darwin University Campus Industry night 2.6 Reception for Aboriginal Rangers hosted by The Hon. -

Associated Minutes of Proceedings Report on Statehood Reference

M LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Associated Minutes of Proceedings Report on Statehood Reference May 2016 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 12th Assembly Legal & Constitutional Affairs Committee Minutes of Proceedings Meeting No. 1 12pm, Wednesday, 31 October 2012 Litchfield Room Present: Ms Lia Finocchiaro (Chair), Member for Drysdale Ms Kezia Purick, Member for Goyder Mrs Bess Price, Member for Stuart Mr Michael Gunner, Member for Fannie Bay Mr Gerald Mccarthy, Member for Barkly In attendance: Julia Knight, Committee Secretary Russell Keith, Clerk Assistant Committees Lauren Copley Orrock, Administration/Research Officer 1. ELECTION OF CHAIR The Secretary called for nominations for Chair. Ms Purick nominated Ms Finocchiaro as Chair of the Legal & Constitutional Affairs Committee. The motion was seconded by Mrs Price and carried. 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF FORMER COMMITTEE MEMBERS The Chair placed on the record her thanks and appreciation to the former Legal & Constitutional Affairs Committee Members, especially the Member for Nightcliff, for their efforts. 3. COIVIMITTEE PROCEDURES (a) Secretariat Support The Committee agreed that hard copies of meeting papers be distributed in the Chamber the morning of future meetings. All papers will also be provided electronically and saved in the LCAC Member's Access folder. It was further agreed that large reports and documents are not to be included in the meeting papers, and can be printed by Members as required. (b) Statements to the Media Mr Gunner moved and Mrs Price seconded That pursuant to Standing Order 274(9d), the Committee authorises the Chair of the Committee to issue media releases and give briefings on matters relating to Legal and Constitutional Affairs and Subordinate Legislation and Publications. -

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 18 October 2016 21 March 2019 001 – 523 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 001 - 008 1 18 October 2016 009 - 014 2 19 October 2016 015 - 017 3 20 October 2016 019 - 023 4 25 October 2016 025 - 029 5 26 October 2016 031 - 035 6 27 October 2016 037 - 040 7 22 November 2016 041 - 045 8 23 November 2016 047 - 050 9 24 November 2016 051 - 055 10 29 November 2016 057 - 063 11 30 November 2016 065 - 068 12 1 December 2016 069 - 073 13 14 February 2017 075 - 079 14 15 February 2017 081 - 084 15 16 February 2017 085 - 088 16 14 March 2017 089 - 094 17 15 March 2017 095 - 098 18 16 March 2017 099 - 107 19 21 March 2017 109 - 111 20 22 March 2017 113 - 116 21 23 March 2017 117 - 121 22 2 May 2017 123 - 126 23 3 May 2017 127 - 129 24 4 May 2017 131 - 135 25 9 May 2017 137 - 142 26 10 May 2017 143 - 150 27 11 May 2017 151 - 157 28 22 June 2017 159 - 163 29 15 August 2017 165 - 169 30 16 August 2017 171 - 176 31 17 August 2017 177 - 181 32 22 August 2017 183 - 186 33 23 August 2017 187 - 192 34 24 August 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 21 March 2019 193 - 196 35 10 October 2017 197 - 199 36 11 October 2017 201 - 203 37 12 October 2017 205 - 208 38 17 October 2017 209 - 213 39 18 October 2017 215 - 220 40 19 October 2017 221 - 225 41 21 November 2017 227 - 233 42 22 November 2017 235 - 247 43 23 -

Labor-Ind Seats CLP-Ind Seats % % 53.9

Northern Territory Electoral Pendulum 2020 Labor 14 Independent 1 CLP 8 Independent 2 Total 15 Majority 5 Total 10 Labor-Ind Seats CLP-Ind Seats % % 25 24.3 Nightcliff Nelson (CLP) 22.8 25 20 20 23 19.3 Sanderson 21 17.7 Arnhem 19 17.3 Wanguri 17 16.6 Johnston Spillett (CLP) 15.1 23 SWING TO LABOR PARTY TO SWING 15 16.3 Gwoja SWING TO COUNTRY LIBERAL PARTY COUNTRY TO SWING 13 16.1 Mulka (Ind) 11 16.0 Casuarina 15 15 Goyder (Ind) 14.4 21 Araluen (Ind) 12.7 19 10 10 9 9.8 Karama 7 9.6 Fannie Bay 8 8 5 7.9 Drysdale 4 4 3 3 2 1 1 2 Arafura C Katherine (CLP) L 3.6 P 3 - I n Braitling (CLP) d Brennan (CLP) Fong Lim Namatjira (CLP) M Daly (CLP) a 2.7 Barkly (CLP) jo Port Darwin 2.4 r it y 1 2.1 17 1.3 3 1.3 Blain L 1.2 a b 0.4 15 o 0.1 r - 13 I 0.2 nd M 11 53.9% Labor aj 46.1% CLP o 9 r 7 ity 5 KEY 3.6 Swing required to take seat 3 Majority in seats Result of general election, 22 August 2020 Northern Territory : Two-Party Preferred Votes by Division, 22 August 2020 Division Labor Votes % CLP Votes % %Swing to CLP %Swing Needed Winner Arafura 1,388 53.57 1,203 46.43 3.2 3.6 Lawrence Costa (Labor) Araluen⁽a⁾ 1,630 37.35 2,734 62.65 3.0 12.7 Robyn Lambley (Ind) Arnhem⁽b⁾ 1,977 67.61 947 32.39 -5.2 17.7 Selena Uibo (Labor) Barkly 1,717 49.90 1,724 50.10 16.0 0.1 Steve Edgington (CLP) Blain 2,095 50.16 2,082 49.84 -1.5 0.2 Mark Turner (Labor) Braitling 2,141 48.71 2,254 51.29 4.4 1.3 Joshua Burgoyne (CLP) Brennan 2,138 48.81 2,242 51.19 3.8 1.2 Marie-Clare Boothby (CLP) Casuarina 3,035 65.96 1,566 34.04 -4.6 16.0 Lauren Moss (Labor) Daly 1,890 48.79 -

Report School-Based Police Program Review May 2019

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REPORT SCHOOL-BASED POLICE PROGRAM REVIEW MAY 2019 1 www.education.nt.gov.au TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents p. 2 Executive Summary p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Background p. 5 A Proposed ‘New’ School Based Policing Framework p. 6 New School-Based Police Model – Police Concept of Operations p. 7 Department of Education School-Based Police Interim Guidelines p. 8 Review Methodology p. 9 Limitations p. 10 Consultation and Findings p. 10 System Perspective p. 10 Highlights of the New School-Based Police Program p. 11 School-Based Police Program Progress p. 11 Department of Education School-Based Police Interim Guidelines - Feedback p. 12 School-Based Police Perspectives p. 13 Student Voice – Program Effectiveness p. 15 Stakeholder Perspectives p. 15 North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency p. 15 Aboriginal Peak Organisations Northern Territory p. 16 Northern Territory Council of Social Services p. 16 Consultation Recurring Themes p. 16 Conclusion p. 17 Recommendations p. 18 Appendix A – Student Voice: Program Effectiveness p. 19 Acknowledgements p. 21 2 www.education.nt.gov.au EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The School-Based Police Program (SBP Program) was launched by the Minister for Education, the Hon Selena Uibo MLA and the Minister for Police, the Hon Nicole Manison MLA, on 17 September 2018. The school-based police program was designed in collaboration with the Department of Education (DoE) and the Northern Territory Council of Government School Organisations (COGSO), the program was launched in ten government schools at the start of Term 4, 2018. The new model aims to address issues raised during the Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory with a greater focus on safety, youth engagement and youth diversion. -

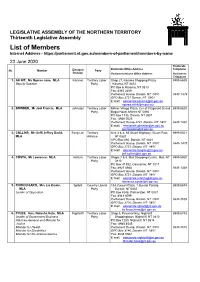

List of Members Internet Address

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Thirteenth Legislative Assembly List of Members Internet Address - https://parliament.nt.gov.au/members-of-parliament/members-by-name 23 June 2020 Electorate Electoral Electorate Office Address Telephone No. Member Party Division Parliament House Office Address Parliament Telephone 1. AH KIT, Ms Ngaree Jane, MLA Karama Territory Labor Shop 27, Karama Shopping Plaza, 8999 6659 Deputy Speaker Party Karama, NT 0812 PO Box 6, Karama, NT 0813 Fax: 8945 2090 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1479 GPO Box 3721 Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 2. BOWDEN, Mr Joel Francis, MLA Johnston Territory Labor Millner Village Plaza, Cnr of Fitzgerald St and 8999 6620 Party Bagot Road, Millner NT 0810 PO Box 1135, Darwin, NT 0801 Fax: 8948 0525 Parliament House 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 8946 1490 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 3. COLLINS, Mr (Jeff) Jeffrey David, Fong Lim Territory Unit 3 & 4, 65 Stuart Highway, Stuart Park, 8999 6501 MLA Alliance NT 0820 GPO Box 892, Darwin, NT 0801 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1475 GPO Box 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 4. COSTA, Mr Lawrence, MLA Arafura Territory Labor Shops 7 & 8, Moil Shopping Centre, Moil, NT 8999 6950 Party 0810 PO Box 41392, Casuarina, NT 0811 Fax: 8927 0988 8946 1438 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 GPO Box 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 5. -

Lambley Clinging on to Alliance

MONDAY AUGUST 24 2020 NEWS 05 EVERY vote counts Number every square in NT LEGISLATIVEVoting is compulsory ASSEMBLY ELECTION 2020 the TerritoryHave your say votes this election day the order of your choice VOTE 1 Four seats still hang in the balance MADURA MCCORMACK AND Neither Chief Minister Mi- NATASHA EMECK IN THIS ELECTION THE chael Gunner nor Opposition INTRODUCTION OF A THIRD Leader Lia Finocchiaro made THE political future of Labor MAJOR PARTY MADE THE an appearance yesterday and frontbencher Selena Uibo and it’s understood the CLP leader candidates in three other key ''DETERMINATION OF THE has not yet called Mr Gunner seats could be decided today as TCP FOR ELECTION NIGHT to concede defeat. the NT Electoral Commission MORE DIFFICULT At the moment Labor has shifts into full count mode. comfortably claimed Fannie The NTEC will be correct- Bay, Wanguri, Nightcliff, Cas- NTEC Natasha Fyles enjoys the ing the two candidate pre- uarina, Karama, Gwoja, Sand- Nightcliff markets on Sunday ferred counts across five seats, erson, Johnston, Port Darwin chatting with Anne Kleinitz and four of which remained in NTEC staff able to finish up in and Drysdale. and Arafura has her niece Billie Boyer, 4. doubt yesterday, as ballot pa- less than three hours. more than likely been won by Picture: CHE CHORLEY pers are recounted. Overall, the postal vote flow Labor’s Lawrence Costa. Algorithms in Arnhem will has had minimal impact on the Labor has maybe lost Brait- switch to projected flows be- outcome thus far, though elec- ling’s Dale Wakefield, though tween Ms Uibo, who is ahead tion boffins, including Tas- Charles Darwin University on first preferences, and inde- mania’s Kevin Bonham and Professor Rolf Gerritsen thinks pendent Ian Gumbula while ABC’s Antony Green, have there’s a slim chance she could Katherine, Fong Lim and Blain tipped Labor’s Sid Vashist to pull through on preference. -

Northern Territory Election Outcome August 2020 on 22 August 2020

Northern Territory election outcome August 2020 On 22 August 2020 Northern Territory Labor was returned to Government, having won a majority of seats in the Northern Territory (NT) Parliament. On Monday 7 September the Chief Minister announced the composition of the new Ministry. Contents Further information................................................................................................................................................ 1 Northern Territory Ministry ................................................................................................................................... 2 Results .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Key influencing factors: .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Seat by seat results................................................................................................................................................. 4 History of Elections 1997-20126 ............................................................................................................................ 5 Chief Minister– The Hon Michael Gunner MP ....................................................................................................... 5 Further information For more information, please contact your Hawker Britton consultant, Queensland and Northern Territory Director, -

August 2020 Election

August 2020 Election WHO & WHERE GUIDE This guide will tell you: - What are the different Electorates in the NT - Which electorate your community, town, homeland or suburb falls into - Who is the current politician for your area, called Member of Parliament (MLA) - Who are some of the other people running to be elected for your area What Letters stand for: If a politican has an Aboriginal flag - MLA - member of Parliament next to their name, that means they ALP - Australian Labor Party identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait CLP- Country Liberal Party Islander Territory Alliance There are three big parties running in the NT election, NT Labor, Country Liberal Party and Territory Alliance. There are also people who run as Independents, and people who run in smaller parties. If an electorate page is yellow, that means an Independent is the representative in Parliament for that area If the electorate page is red, that means Labor are the representatives for that area If an electorate page is organge, that means Country Liberal party are the representatives for that area And if it is dark blue, that means Territory Alliance are the representaives for that area. Authorised by A.Telford of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, Queen St Brisbane, Printed and funded by Seed Indigenous Climate Network MULKA Where: Nhulunbuy, Galiwinku, Yirrkala, Ramingining, Galinwinku Current MLA: Mr Yingiya (Mark) Guyula (Independent) ALP candidate: Lynne Walker Authorised by A.Telford of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, Queen St Brisbane, Printed and funded by Seed Indigenous Climate Network Barkly Where: Barkly Tableland, the regional centre of Tennant Creek and the communities of Ali Curung, Alpurrurulam, Ampilatwatja, Arlparra, Borroloola, Daly Waters, Elliott, Larrimah, and Ti Tree. -

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY of the NORTHERN TERRITORY Thirteenth Legislative Assembly

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Thirteenth Legislative Assembly List of Members – Internet Address - http://www.nt.gov.au/lant 9 January 2017 Electorate Electoral Electorate Office Address Telephone No. Member Party Division Parliament House Office Address Parliament Telephone 1. AH KIT, Ngaree Jane, MLA Karama A.L.P Shop 27, Karama Shopping Plaza, 8999 6659 Karama, NT 0812 PO Box 6, Karama, NT 0813 Fax: 8945 2090 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1411 GPO Box 3721 Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 2. COLLINS, (Jeff) Jeff rey David , MLA Fong Lim A.L.P Unit 4 & 5, 65 Stuart Highway, Stuart Park, 8999 6501 NT 0820 GPO Box 892, Darwin, NT 0801 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1475 GPO Box 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 3. COSTA, Lawrence, MLA Arafura A.L.P Shop 7 & 8, Moil Shopping Centre, Moil, NT 8999 6950 0810 PO Box 41392, Casuarina, NT 0811 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1438 GPO Box 3721, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 4. FINOCCHIARO, Lia Emele, MLA Spillett C.L. Shop 20, Winnellie Shopping Centre, 8999 6667 Deputy Leader of Opposition Winnellie, NT 0820 Opposition Whip PO Box 4248, Palmerston, NT 0831 Fax: 8941 8099 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8946 1471 GPO Box 3700, Darwin, NT 0801 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 5. FYLES, Hon. Natasha Kate, MLA Nightcliff A.L.P Shop 5, Pavonia Way, Nightcliff 8999 6743 Leader of Government Business Shoppingtown, Nightcliff, NT 0810 Attorney-General and Minister for Justice PO Box 1283, Nightcliff, NT 0814 Minister for Health Fax: 8985 4545 Parliament House, Darwin, NT 0800 8936 5610 GPO Box 3146, Darwin, NT 0801 Fax: 8936 5562 E:mail: [email protected] [email protected] 6. -

SOMERVILLE.ORG.AU I Photo: Margaret Somerville Award Winner Vicki Borzi with Somerville President Daphne Read AO

SOMERVILLE.ORG.AU i Photo: Margaret Somerville Award winner Vicki Borzi with Somerville President Daphne Read AO. The Directors on the Board during the 2015/16 Directors’ meetings held during the financial year: financial year were: • September 2015 (Annual General Meeting) • Daphne Read AO – President • November 2015 • Chris Tudor AM – Vice President • February 2016 • Vicki O’Halloran AM – Public Officer • May 2016 • Margaret Black • Bruce March PSM Life Members • Phil Johnson • Kevin Kennedy • Daphne Read AO • John Edwards • Margaret Black • Meredith Day • Gweneth Davies • Andrew Caddy • Ron Brandt • Clare Martin • Barry Prior (dec) • Ben Gill • John Duguid • Amin Islam FCA ii ANNUAL REPORT 2016 SOMERVILLE.ORG.AU 1 President & Chief Executive Officer’s Reports Governance During the year Somerville staff proudly accepted a number of We welcomed new Board Member, Awards. Liza Metcalfe won the Final Thoughts Amin Islam FCA, who comes to Northern Territory Australian Institute I am honoured to once again take us with a wealth of business and of Management’s Not for Profit on the role of President of the Board accounting experience, and will join a Manager of the Year. Mavis White of Somerville Community Services group of like-minded, knowledgeable won the Northern Territory Disability and I especially congratulate and and skilled people who make up the Services Awards’ Outstanding thank our CEO Vicki O’Halloran AM Somerville Board. Disability Service Employee. Deborah for her outstanding leadership and Bampton was the winner of the positive profile which contributes to The realignment of Somerville’s Northern Territory Telstra Business the success of our organisation. Her business model to ensure that it is Woman of the Year For Purpose and dedication allows her to handle an positioned for future funding models Social Enterprise Award.