The Brighton 'Grand Hotel' Bombing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Counter-Aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing

Notes Chapter One Introduction: Taoibh Amuigh agus Faoi Ghlas: The Counter-aesthetics of Republican Prison Writing 1. Gerry Adams, “The Fire,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 37. 2. Ibid., 46. 3. Pat Magee, Gangsters or Guerillas? (Belfast: Beyond the Pale, 2001) v. 4. David Pierce, ed., Introduction, Irish Writing in the Twentieth Century: A Reader (Cork: Cork University Press, 2000) xl. 5. Ibid. 6. Shiela Roberts, “South African Prison Literature,” Ariel 16.2 (Apr. 1985): 61. 7. Michel Foucault, “Power and Strategies,” Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980) 141–2. 8. In “The Eye of Power,” for instance, Foucault argues, “The tendency of Bentham’s thought [in designing prisons such as the famed Panopticon] is archaic in the importance it gives to the gaze.” In Power/ Knowledge 160. 9. Breyten Breytenbach, The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983) 147. 10. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 4. 11. Ibid. 12. William Wordsworth, “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” The Norton Anthology of English Literature vol. 2A, 7th edition, ed. M. H. Abrams et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000) 250. 13. Gerry Adams, “Inside Story,” Republican News 16 Aug. 1975: 6. 14. Gerry Adams, “Cage Eleven,” Cage Eleven (Dingle: Brandon, 1990) 20. 15. Wordsworth, “Preface” 249. 16. Ibid., 250. 17. Ibid. 18. Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1990) 27. 19. W. B. Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: Macmillan, 1961) 521–2. 20. Bobby Sands, One Day in My Life (Dublin and Cork: Mercier, 1983) 98. -

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

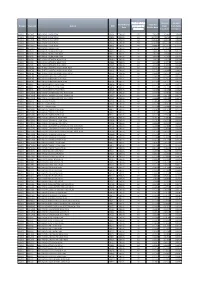

Domain Stationid Station UDC Performance Date

Number of days Amount Amount Performance Total Per Domain StationId Station UDC processed for from from Public Date Minute Rate distribution Broadcast Reception RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 NON PEAK BRA01 CENSUS 92 7.8347 4.2881 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 LOW PEAK BRB01 CENSUS 92 10.7078 7.1612 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 HIGH PEAK BRC01 CENSUS 92 13.5380 9.9913 3.5466 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 NON PEAK BRA02 CENSUS 92 17.4596 11.2373 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 LOW PEAK BRB02 CENSUS 92 24.9887 18.7663 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 HIGH PEAK BRC02 CENSUS 92 32.4053 26.1830 6.2223 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA NON PEAK BRA10 CENSUS 92 1.4814 1.4075 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA LOW PEAK BRB10 CENSUS 92 2.4245 2.3506 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA HIGH PEAK BRC10 CENSUS 92 3.3534 3.2795 0.0739 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK NON PEAK BRA65 CENSUS 92 1.4691 1.4593 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK LOW PEAK BRB65 CENSUS 92 2.4468 2.4371 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK HIGH PEAK BRC65 CENSUS 92 3.4100 3.4003 0.0098 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO NON PEAK BRA62 CENSUS 92 0.1516 0.1104 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO LOW PEAK BRB62 CENSUS 92 0.2256 0.1844 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO HIGH PEAK BRC62 CENSUS 92 0.2985 0.2573 0.0411 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE NON PEAK BRA64 CENSUS 92 0.0803 0.0569 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE LOW PEAK BRB64 CENSUS 92 0.1184 0.0951 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE HIGH PEAK BRC64 CENSUS 92 0.1560 0.1327 0.0233 RADIO BRBRIS BBC -

June/July 2012

Hollingdeannews June/July 2012 an independent newspaper produced and delivered to your door by your neighbours Summer’s here at last! This photo and several others of a carnival parade going up Davey Drive were kindly given to us for our local history collection. We don’t have a date but it looks 1970’s. Do you remember this event or have any photos of other festivals in Hollingdean? We’d love to hear from you! Photo: Hollingdean News collection Come along to our Garden Party/Coffee Morning 50 Hertford Road Brighton 10.30 - 1.30pm. Saturday 23rd June. We are raising funds for a local Cat Charity 'Kitty in the City' Enjoy a coffee on the lawn and a natter with your friends and neighbours. Homemade cakes Hertford Infant & Nursery School and a plant stall, also a raffle Hertford Road BN1 7GF and childrens games. Do please come SUMMER FAIR and support us. Saturday 14th July 11-3.00pm, Sporting theme - come dressed as a country or sports person for a chance to win a medal! J o n J o s e p h East Sussex Fire and Rescue team will be at the school gates at 11am (as long as there are M O B I L E no fires to put out!) for everyone to see their fire engine. M E C H A N I C Face painting - Barbecue - Tombola - Cream teas 30 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE Penalty Shoot Out football - Bouncy castle Fully Qualified Current CPD Fully Insured NO VAT ON LABOUR Pop along for a fun filled day and best of all it's Member of The Institute of The Motor Industry FREE! We look forward to seeing you all there. -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

Terrorism Knows No Borders

TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS October 2019 his is a special initiative for SEFF to be associated with, it is one part of a three part overall Project which includes; the production of a Book and DVD Twhich captures the testimonies and experiences of well over 20 innocent victims and survivors of terrorism from across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland. The Project title; ‘Terrorism knows NO Borders’ aptly illustrates the broader point that we are seeking to make through our involvement in this work, namely that in the context of Northern Ireland terrorism and criminal violence was not curtailed to Northern Ireland alone but rather that individuals, families and communities experienced its’ impacts across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and beyond these islands. This Memorial Quilt Project does not claim to represent the totality of lives lost across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland but rather seeks to provide some understanding of the sacrifices paid by communities, families and individuals who have been victimised by ‘Republican’ or ‘Loyalist’ terrorism. SEFF’s ethos means that we are not purely concerned with victims/survivors who live within south Fermanagh or indeed the broader County. -

The Sade Boom Beckett Kept a Keen Interest in the Works and Person of the Marquis De Sade All His Life

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72683-2 — Beckett and Sade Jean-Michel Rabaté Excerpt More Information Beckett and Sade 1 Introduction: The Sade Boom Beckett kept a keen interest in the works and person of the Marquis de Sade all his life. Quite late, he became conscious that he had participated in a ‘Sade boom’, dating from the inception of French Surrealism, from Guillaume Apollinaire, André Breton and Georges Bataille to the explosion of Sadean scholarship in the 1950s. Even if Beckett realized that he had been caught up in a Sade cult, he never abjured his faith in the importance of the outcast and scandalous writer, and kept rereading Sade (as he did Dante) across the years.1 I will begin by surveying Beckett’s letters to find the traces of his readings and point out how a number of hypotheses concerning the ‘divine Marquis’ evolved over time. Beckett revisited Sade several times, and he progressively reshaped and refined his interpretation of what Sade meant for him across five decades. Following the evolution of these epistolary markers that culminated in a more political reading, I will distinguish four moments in Beckett’s approach. Beckett knew the details of Sade’s exceptional life, a life that was not a happy one but was certainly a long one, for his career spanned the Old Regime, the French Revolution and almost all of the First Empire. Sade was jailed for debauchery from 1777 to 1790, then imprisoned for a short time at the height of the Terror in 1793–4, which allowed him to witness the mass slaughter; he was freed just before the date set for his execution, thanks to Robespierre’s downfall; he was jailed again for his pornographic writings under the Consulate and the Empire under direct orders from a puritanical Napoleon, between 1801 and 1814. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Leninist Perspective on Triumphant Irish National-Liberation Struggle

Only he is a Marxist who extends the rec- Subscriptions (£30 p.a. or £15 six months - pay og Bulletin Publications) and circulation: £2 nition of the class struggle to the recogni- Economic & tion of the dictatorship of the proletariat. p&p epsr, po box 76261, This is the touchstone on which the real Philosophic London sw17 1GW [Post Office Registered.] Books understanding and recognition of Marxism e-Mail: [email protected] is to be tested. V.I.Lenin Science Review Website — WWW.epsr.orG.uk Vol 15 driver (representing Britain’s Leninist perspective on triumphant police-military dictatorship), and that the IRA itself intended to hold an inquiry to reprimand Irish national-liberation struggle those responsible for such an ill-judged attack, plus well- Part Two (June 1988 - January 1994) recorded apologies (for the casu- alties to innocent by-standers) expressed by Sinn Féin and the IRA. EPSR books Volume 15 [Part One in Vol 8 1979-88] Channel Four’s News at Seven even added a postscript to its far further afield, particularly hour-long nightly bulletin that More clues from the dog not barking in the Republic and in the huge its coverage of the Fermanagh [ILWP Bulletin No 450 29-06-88] North American Irish-descent border incident should have population). made it clearer that the target Pieces continue to fit together again showed up the limits of Some key sections of the Brit- of the IRA attack was the UDR revealing British imperialism’s philosophical, political and ish capitalist state media delib- bus driver, and not the children plans to finally quit its colonial cultural emancipation of the erately held back from this prize inside the bus. -

IRMP Media Coverage

IRMP Media Coverage 20th April Eastbourne Herald- Online https://www.eastbourneherald.co.uk/news/people/major-changes-way-east-sussex-fire-service- 2544064 21st April Splash FM http://www.pressdata.co.uk/viewbroadcast.asp?a_id=20849624 Splash FM http://www.pressdata.co.uk/viewbroadcast.asp?a_id=20864426 22nd April Brighton and Hove News https://www.brightonandhovenews.org/2020/04/22/fewer-jobs-and-flexible-rosters-proposed-by- fire-chiefs/ 23rd April The Argus https://www.theargus.co.uk/news/18394270.east-sussex-fire-authority-set-face-major-shake-up/ 24th April Splash FM http://www.pressdata.co.uk/viewbroadcast.asp?a_id=20871148 Brighton and Hove News https://www.brightonandhovenews.org/2020/04/24/fire-chiefs-to-consult-on-shake-up-despite- coronavirus-concerns/ Eastbourne Herald (Paper Page 9) Calls for delay over ' drastic changes' to the fire service Sussex Express (Paper Page 9) Delay ' drastic' changes to the fire service until after the pandemic say union chiefs 27th April The Argus https://www.theargus.co.uk/news/18406814.east-sussex-firefighters-furious-proposed-cuts/ Uckfield News https://uckfieldnews.com/cuts-proposed-for-uckfield-fire-station/ Bexhill Observer https://www.bexhillobserver.net/news/politics/firefighters-union-warns-major-threat-public-safety- around-east-sussex-changes-2551694 The Argus- (Paper- Page 9) Firefighters up in arms Eastbourne Herald https://www.eastbourneherald.co.uk/news/politics/firefighters-union-warns-major-threat-public- safety-around-east-sussex-changes-2551694 Hastings Observer