THE FUTURE IS LATINX October 8 — December 3, 2020 | Opening Reception, October 8, 4 - 6 P.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson Plan Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

“Portraiture Now: Staging the Self” Lesson Plan Compiled by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Target Grade Level: 9–12 in English language arts, Spanish, and visual arts Objectives After completing this lesson, students will be able to: • Identify and analyze key components of a portrait and relate visual elements to relevant cultural context and significance • Analyze how multiple portraits address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the artists take • Create a series of critical thinking questions appropriate to a specific purpose and audience Portraits Use the following portraits from the online exhibition “Portraiture Now: Staging the Self” at http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/index.html: • David Antonio Cruz, iwishrainydayscamewithasliceofmango, http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/cruz.html • Carlee Fernandez, The Strand That Holds Us Together, http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/fernandez.html • María Martínez-Cañas, Duplicity as Identity: 50%, http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/martinez_canas.html • Rachelle Mozman, El Espejo (The Mirror), http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/mozman.html • Karen Miranda Rivadeneira, My mom braiding my hair like her mother did to her, ca. 1990, http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/rivadeneira.html • Michael Vasquez, The Neighborhood Tour, http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/staging/vasquez.html Materials • “Reading” Portraiture Guide for Educators, found at http://www.npg.si.edu/docs/reading.pdf Background Information About the Exhibition “Staging the Self” is the ninth installation of “Portraiture Now,” a series of exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery that showcase some of the twenty-first-century’s most creative portrait artists. -

Your Family's Guide to Explore NYC for FREE with Your Cool Culture Pass

coolculture.org FAMILY2019-2020 GUIDE Your family’s guide to explore NYC for FREE with your Cool Culture Pass. Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org WELCOME TO COOL CULTURE! Whether you are a returning family or brand new to Cool Culture, we welcome you to a new year of family fun, cultural exploration and creativity. As the Executive Director of Cool Culture, I am excited to have your family become a part of ours. Founded in 1999, Cool Culture is a non-profit organization with a mission to amplify the voices of families and strengthen the power of historically marginalized communities through engagement with art and culture, both within cultural institutions and beyond. To that end, we have partnered with your child’s school to give your family FREE admission to almost 90 New York City museums, historic societies, gardens and zoos. As your child’s first teacher and advocate, we hope you find this guide useful in adding to the joy, community, and culture that are part of your family traditions! Candice Anderson Executive Director Cool Culture 2020 Cool Culture | 2019-2020 Family Guide | coolculture.org HOW TO USE YOUR COOL CULTURE FAMILY PASS You + 4 = FREE Extras Are Extra Up to 5 people, including you, will be The Family Pass covers general admission. granted free admission with a Cool Culture You may need to pay extra fees for special Family Pass to approximately 90 museums, exhibits and activities. Please call the $ $ zoos and historic sites. museum if you’re unsure. $ More than 5 people total? Be prepared to It’s For Families pay additional admission fees. -

El Museo Del Barrio 50Th Anniversary Gala Honoring Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Raphael Montañez Ortíz, and Craig Robins

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE EL MUSEO DEL BARRIO 50TH ANNIVERSARY GALA HONORING ELLA FONTANALS-CISNEROS, RAPHAEL MONTAÑEZ ORTÍZ, AND CRAIG ROBINS For images, click here and here New York, NY, May 5, 2019 - New York Mayor Bill de Blasio proclaimed from the stage of the Plaza Hotel 'Dia de El Museo del Barrio' at El Museo's 50th anniversary celebration, May 2, 2019. "The creation of El Museo is one of the moments where history started to change," said the Mayor as he presented an official proclamation from the City. This was only one of the surprises in a Gala evening that honored Ella Fontanals-Cisneros, Craig Robins, and El Museo's founding director, artist Raphael Montañez Ortiz and raised in excess of $1.2 million. El Museo board chair Maria Eugenia Maury opened the evening with spirited remarks invoking Latina activist Dolores Huerta who said, "Walk the streets with us into history. Get off the sidewalk." The evening was MC'd by WNBC Correspondent Lynda Baquero with nearly 500 guests dancing in black tie. Executive director Patrick Charpenel expressed the feelings of many when he shared, "El Museo del Barrio is a museum created by and for the community in response to the cultural marginalization faced by Puerto Ricans in New York...Today, issues of representation and social justice remain central to Latinos in this country." 1230 Fifth Avenue 212.831.7272 New York, NY 10029 www.elmuseo.org Artist Rirkrit Travanija introduced longtime supporter Craig Robins who received the Outstanding Patron of Art and Design Award. Craig graciously shared, "The growth and impact of this museum is nothing short of extraordinary." El Museo chairman emeritus and artist, Tony Bechara, introduced Ella Fontanals-Cisneros who received the Outstanding Patron of the Arts award, noting her longtime support of Latin artists including early support Carmen Herrera, both thru acquiring her work and presenting it at her Miami institution, Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO). -

Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 in & Around, NYC

2015 NEW YORK Association of Art Museum Curators 14th Annual Conference & Meeting May 9 – 12, 2015 Around Town 2015 Annual Conference & Meeting Saturday, May 9 – Tuesday, May 12 In & Around, NYC In addition to the more well known spots, such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, , Smithsonian Design Museum, Hewitt, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, The Frick Collection, The Morgan Library and Museum, New-York Historical Society, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, here is a list of some other points of interest in the five boroughs and Newark, New Jersey area. Museums: Manhattan Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 (212) 288-6400 http://asiasociety.org/new-york Across the Fields of arts, business, culture, education, and policy, the Society provides insight and promotes mutual understanding among peoples, leaders and institutions oF Asia and United States in a global context. Bard Graduate Center Gallery 18 West 86th Street New York, NY 10024 (212) 501-3023 http://www.bgc.bard.edu/ Bard Graduate Center Gallery exhibitions explore new ways oF thinking about decorative arts, design history, and material culture. The Cloisters Museum and Garden 99 Margaret Corbin Drive, Fort Tyron Park New York, NY 10040 (212) 923-3700 http://www.metmuseum.org/visit/visit-the-cloisters The Cloisters museum and gardens is a branch oF the Metropolitan Museum oF Art devoted to the art and architecture oF medieval Europe and was assembled From architectural elements, both domestic and religious, that largely date from the twelfth through fifteenth century. El Museo del Barrio 1230 FiFth Avenue New York, NY 10029 (212) 831-7272 http://www.elmuseo.org/ El Museo del Barrio is New York’s leading Latino cultural institution and welcomes visitors of all backgrounds to discover the artistic landscape of Puerto Rican, Caribbean, and Latin American cultures. -

YOUR DECOLONIZING TOOLKIT an Evening of Performance Art Featuring

YOUR DECOLONIZING TOOLKIT An Evening of Performance Art Featuring DOMINIQUE DUROSEAU “A Rap on Race with Rice” 7p KANENE HOLDER, MICHAEL WIGGINS “Say What So What Now What” 8p SHANI HA and AMELIE GAULIER-BRODY “Embody” 8.30p DAVID ANTONIO CRUZ “The Piano Piece” 9p MARIA HUPFIELD, ESTHER NEFF, and IV CASTELLANOS “Feet on the Ground” 9.30p Curated by AYANA EVANS and ANNA MIKAELA EKSTRAND Friday, October 21, 7-10p 56 Henry St. #SE, New York, NY 10002 www.maw.guru [email protected] Embody, Shani Ha. Photo courtesy of artist. Decolonization is defined as the act of freeing a country/people from being dependent on and oppressed by a more aggressive culture. For this evening of performance art nine artists will take on race, sexuality, and body politics to fuel “Your Decolonizing Toolkit.” You are invited to talk about race with Dominique Duroseau in her piece "A Rap on Race with Rice;" this literal work starkly contrasts Shani Ha’s textile sculptures that are an abstract investigation of social boundaries. To break conventions of silencing Kanene Holder will perform her word association piece based on current affairs and David Antonio Cruz will perform “The Piano Piece,” a celebrated piece that deals with his queer-Latino identity, on the street. The evening will culminate in actions of deconstructing as exhibited in the performance collaboration between Maria Hupfield, Esther Neff and IV Castellanos In light of America’s current political situation where complex issues of discrimination based on race and sexuality are being investigated, decolonization of the mind is more important than ever. -

STATE of HIGHER EDUCATION for LATINX in CALIFORNIA

STATE OF HIGHER EDUCATION for LATINX IN CALIFORNIA NOVEMBER 2018 The contributions of countless Latinx have characterized the spirit of Cesar Chavez Dolores Huerta Carlos Santana Edward Roybal California. Labor organizer Labor organizer Musician Politician Cruz Reynoso Antonia Ellen Ochoa Mario J. Molina Luis Sanchez Helen Torres CA Supreme Hernandez Astronaut Chemist and Civil and voting Women’s rights Court Justice Civil rights leader Nobel Prize rights advocate advocate & philanthropist winner Patricia Gandara Maria Blanco Estela Bensimon Thomas A. Saenz Maria Angelica Salas Professor and Attorney and Professor and Civil rights Contreras-Sweet Immigrant rights civil rights immigrant rights higher education attorney Business woman advocate advocate advocate equity advocate Linda Griego Mike Krieger Monica Lozano Sal Castro Martha Arevalo Alberto Retana Business Instagram Business woman Teacher Immigrant rights Community woman2 | STATE OF HIGHERco-founder EDUCATION FORand LATINXphilanthropist IN CALIFORNIA | THE CAMPAIGNadvocate FOR COLLEGE OPPORTUNITYorganizer Introduction California has been known as a land of opportunity and a place that rewards audacity, ingenuity, and courageousness. The determination, innovations, and contributions of countless Latinxi have characterized the spirit of this great state. From California’s earliest Mexican-American Governors, the critical agricultural labor that helps feed our nation, the patriotism of hundreds of thousands of Latinx who serve in our armed forces and run small businesses, the influence -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

Chicanx (Re)-Claiming Identity and Representation Through Education

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 12-2016 Chicanx (Re)-Claiming Identity and Representation Through Education Katherin Razo-Gomez California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Recommended Citation Razo-Gomez, Katherin, "Chicanx (Re)-Claiming Identity and Representation Through Education" (2016). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 62. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/62 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chicanx (Re)-Claiming Identity and Representation Through Education Photo of Daniela Barajas and Katherin Razo-Gomez, CSUMB Commencement May 2016. Katherin Razo-Gomez Senior Capstone Chicano/a Studies Research Essay Dr. Wang Division of Humanities and Communication California State University, Monterey Bay Fall 2016 Dedication To my Mom and Dad, whose “American Dream” is seeing their children receive the education they were never able to acquire. To my siblings Jorge Luis, Viviana and Valeria, you are my strength and motivation. To all the immigrant families, this is for all of you. “Feet, why do I need them if I have wings to fly.” -Frida Kahlo Acknowledgements I’d like to thank the HCOM department and especially Dr. Villasenor for leading me and helping me achieve my goal. For always being so heartwarming, encouraging, and provided feedback necessary for me to grow as a student. -

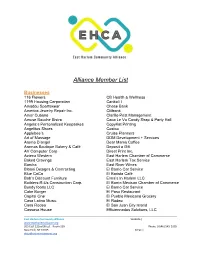

Alliance Member List

Alliance Member List Businesses 116 Flowers CB Health & Wellness 1199 Housing Corporation Cenkali I Amadou Sportswear Chase Bank America Jewelry Repair Inc. Citibank Amor Cubano Clarillo Pest Management Amuse Bauche Bistro Coco Le Vu Candy Shop & Party Hall Angela;s Personalized Keepsakes CopyKat Printing Angelitos Shoes Costco Applebee’s Cruise Planners Art of Massage DDM Development + Services Aroma D’angel Dear Mama Coffee Aromas Boutique Bakery & Café Deposit a Gift AV Computer Corp Direct Print Inc. Azteca Western East Harlem Chamber of Commerce Baked Cravings East Harlem Tax Service Barcha East River Wines Blooni Designs & Contracting El Barrio Car Service Blue CoCo El Barista Café Bob’s Discount Furniture Elma’s In Harlem LLC Builders-R-Us Construction Corp. El Barrio Mexican Chamber of Commerce Bundy foods LLC El Barrio Car Service Cake Burger El Paso Restaurant Capital One El Pueblo Mexicano Grocery Casa Latina Music El Rodeo Casa Rodeo El San Juan City Island Cassava House Efficiennados Solutions, LLC East Harlem Community Alliance Website | www.eastharlemalliance.org 205 East 122nd Street - Room 220 Phone | (646) 545-5205 New York, NY 10035 Email | [email protected] Euromex Soccer Play Up Studio Evelyn’s Kitchen Plaza Mexico Event by Debbie King Ponce Bank Fierce Nail Spa Salon Popular Bank GinJan Bros LLC Rancho Vegado Inc. Harlem Shake Result Media Team Gotham To Go R&M Party Supply Store GM Pest Control Rancho Vegado Corp Heavy Metal Bike Shop The Roast NYC IHOP The Rosario Group JC-1 Graph-X Sabor Borinqueño La Costeñito Grocery Sam’s Pizzeria La Reina Del Barrio Inc. -

Allá Y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(S)

Diálogo Volume 5 Number 1 Article 4 2001 Allá y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(s) Miriam Jiménez Román Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Jiménez Román, Miriam (2001) "Allá y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(s)," Diálogo: Vol. 5 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol5/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Allá y Acá: Locating Puerto Ricans in the Diaspora(s) Cover Page Footnote This article is from an earlier iteration of Diálogo which had the subtitle "A Bilingual Journal." The publication is now titled "Diálogo: An Interdisciplinary Studies Journal." This article is available in Diálogo: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol5/iss1/4 IN THE DIASPORA(S) Acá:AlláLocatingPuertoRicansy ©Miriam ©Miriam Jiménez Román Yo soy Nuyorican.1 Puerto Rico there was rarely a reference Rico, I was assured that "aquí eso no es Así es—vengo de allá. to los de afuera that wasn't, on some un problema" and counseled as to the Soy producto de la migración level, derogatory, so that even danger of imposing "las cosas de allá, puertorriqueña, miembro de la otra compliments ("Hay, pero tu no pareces acá." Little wonder, then, that twenty- mitad de la nación. -

Crafting Colombianidad: Race, Citizenship and the Localization of Policy in Philadelphia

CRAFTING COLOMBIANIDAD: RACE, CITIZENSHIP AND THE LOCALIZATION OF POLICY IN PHILADELPHIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Diane R. Garbow July 2016 Examining Committee Members: Judith Goode, Advisory Chair, Department of Anthropology Naomi Schiller, Department of Anthropology Melissa Gilbert, Department of Geography and Urban Studies Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas, External Member, City University of New York © Copyright 2016 by Diane R. Garbow All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT In contrast to the municipalities across the United States that restrict migration and criminalize the presence of immigrants, Philadelphia is actively seeking to attract immigrants as a strategy to reverse the city’s limited economic and political importance caused by decades of deindustrialization and population loss. In 2010, the population of Philadelphia increased for the first time in six decades. This achievement, widely celebrated by the local government and in the press, was only made possible through increased immigration. This dissertation examines how efforts to attract migrants, through the creation of localized policy and institutions that facilitate incorporation, transform assertions of citizenship and the dynamics of race for Colombian migrants. The purpose of this research is to analyze how Colombians’ articulations of citizenship, and the ways they extend beyond juridical and legal rights, are enabled and constrained under new regimes of localized policy. In the dissertation, I examine citizenship as a set of performances and practices that occur in quotidian tasks that seek to establish a sense of belonging. Without a complex understanding of the effects of local migration policy, and how they differ from the effects of federal policy, we fail to grasp how Philadelphia’s promotion of migration has unstable and unequal effects for differentially situated actors. -

The Class and Gender Dimensions of Puerto Rican Migration to Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1993 The class and gender dimensions of Puerto Rican migration to Chicago Maura I. Toro-Morn Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Toro-Morn, Maura I., "The class and gender dimensions of Puerto Rican migration to Chicago" (1993). Dissertations. 3025. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3025 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1993 Maura I. Toro-Morn LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CLASS AND GENDER DIMENSIONS OF PUERTO RICAN MIGRATION TO CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND ANTHROPOLOGY BY MAURA I. TORO-MORN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY, 1993 Copyright, 1993, Maura I. Toro-Morn All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study would not have been possible without the careful reading, support and guidance of my dissertation advisor, Dr. Judith Wittner, who labor with me through innumerable drafts. I am also grateful to Dr. Peter Whalley and Dr. Maria Canabal for their help and confidence in me. My husband, Dr. Frank Morn, provided the everyday support, love, and excitement about the project to get me though the most difficult parts of completing this work.